2 Medical Language Related to the Body as a Whole

WTCS Learning Objectives

- Use the anatomic reference system to identify the anatomic position of the body

- Use the anatomic reference system to identify the body planes

- Use the anatomic reference system to identify the body cavities

- Use the anatomic reference system to identify the directional terms

- Use the anatomic reference system to identify the divisions of the body

- Describe the structural organization of the body

- Apply the rules of medical language

- Identify meanings of key word components

As you memorize the language components of medical terminology it is important to support that learning within the context of anatomy and physiology. Proceeding through the body system chapters you will learn word parts, whole medical terms, and common abbreviations. It is important to put into context where in the body the medical term is referencing, and then consider how it works within the body.

Anatomy focuses on structure and physiology focuses on function. Much of the study of physiology centers on the body’s tendency toward homeostasis .

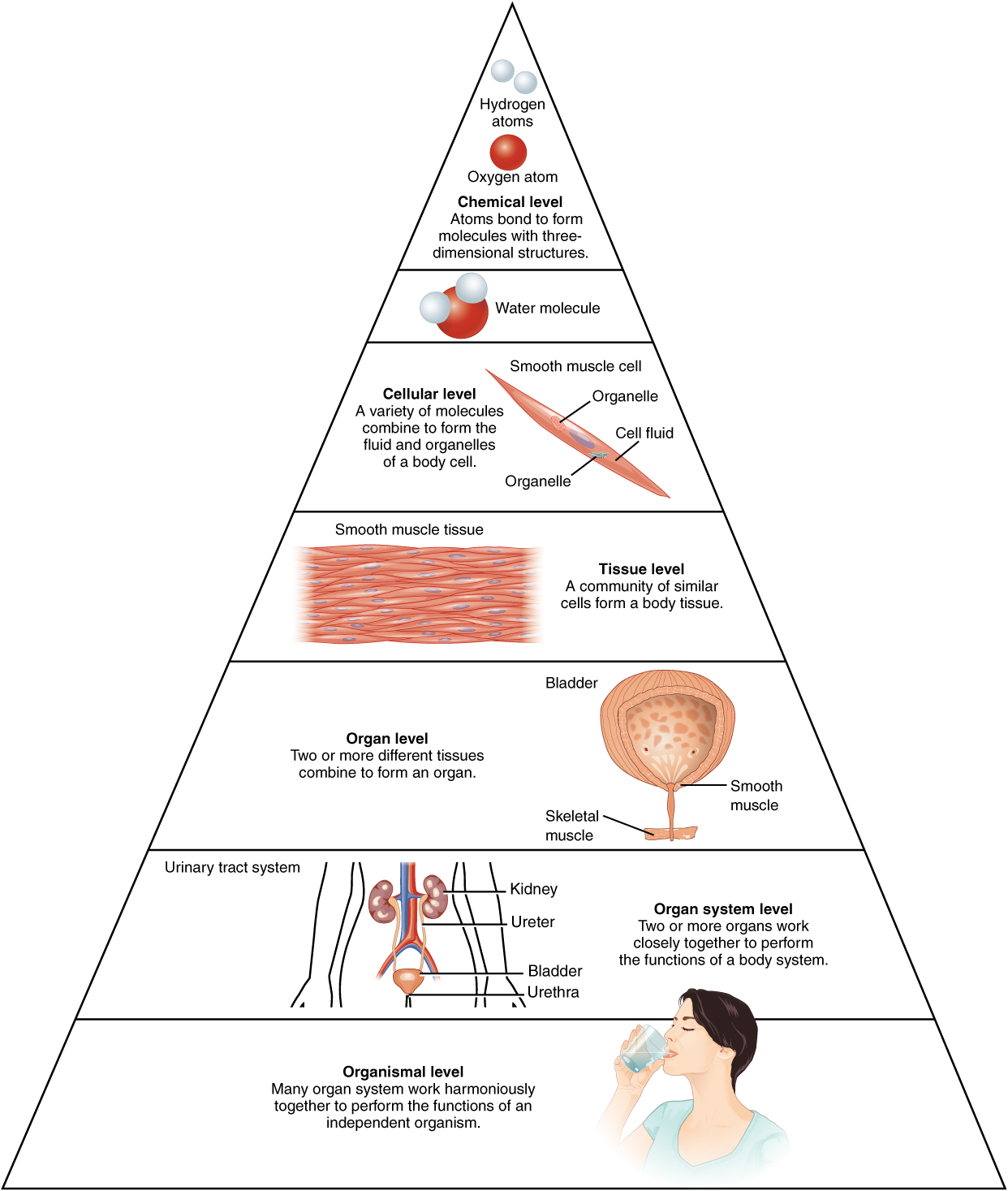

Consider the structures of the body in terms of fundamental levels of organization that increase in complexity: subatomic particles, atoms, molecules, organelles, cells, tissues, organs, organ systems, organisms, and biosphere (Figure 2.1).

The Levels of Organization

All matter in the universe is composed of one or more unique pure substances called elements, familiar examples are hydrogen, oxygen, carbon, nitrogen, calcium, and iron.

- The smallest unit of any of these pure substances (elements) is an atom.

- Atoms are made up of subatomic particles such as the proton, electron, and neutron.

- Two or more atoms combine to form a molecule, such as the water molecules, proteins, and sugars found in living things.

- Molecules are the chemical building blocks of all body structures.

- A cell is the smallest independently functioning unit of a living organism.

- Even bacteria, which are extremely small, independently-living organisms, have a cellular structure. Each bacterium is a single cell. All living structures of human anatomy contain cells, and almost all functions of human physiology are performed in cells or are initiated by cells

- A human cell typically consists of flexible membranes that enclose cytoplasm, a water-based cellular fluid, together with a variety of tiny functioning units called organelles. In humans, as in all organisms, cells perform all functions of life.

- A tissue is a group of many similar cells (though sometimes composed of a few related types) that work together to perform a specific function.

- An organ is an anatomically distinct structure of the body composed of two or more tissue types. Each organ performs one or more specific physiological functions.

An organ system is a group of organs that work together to perform major functions or meet the physiological needs of the body.

Did you know?

- Organs are very collaborative and work with multiple body systems.

- For example, the heart (cardiovascular system) and lungs (respiratory system) work together to deliver oxygen throughout the body and remove carbon dioxide from the body.

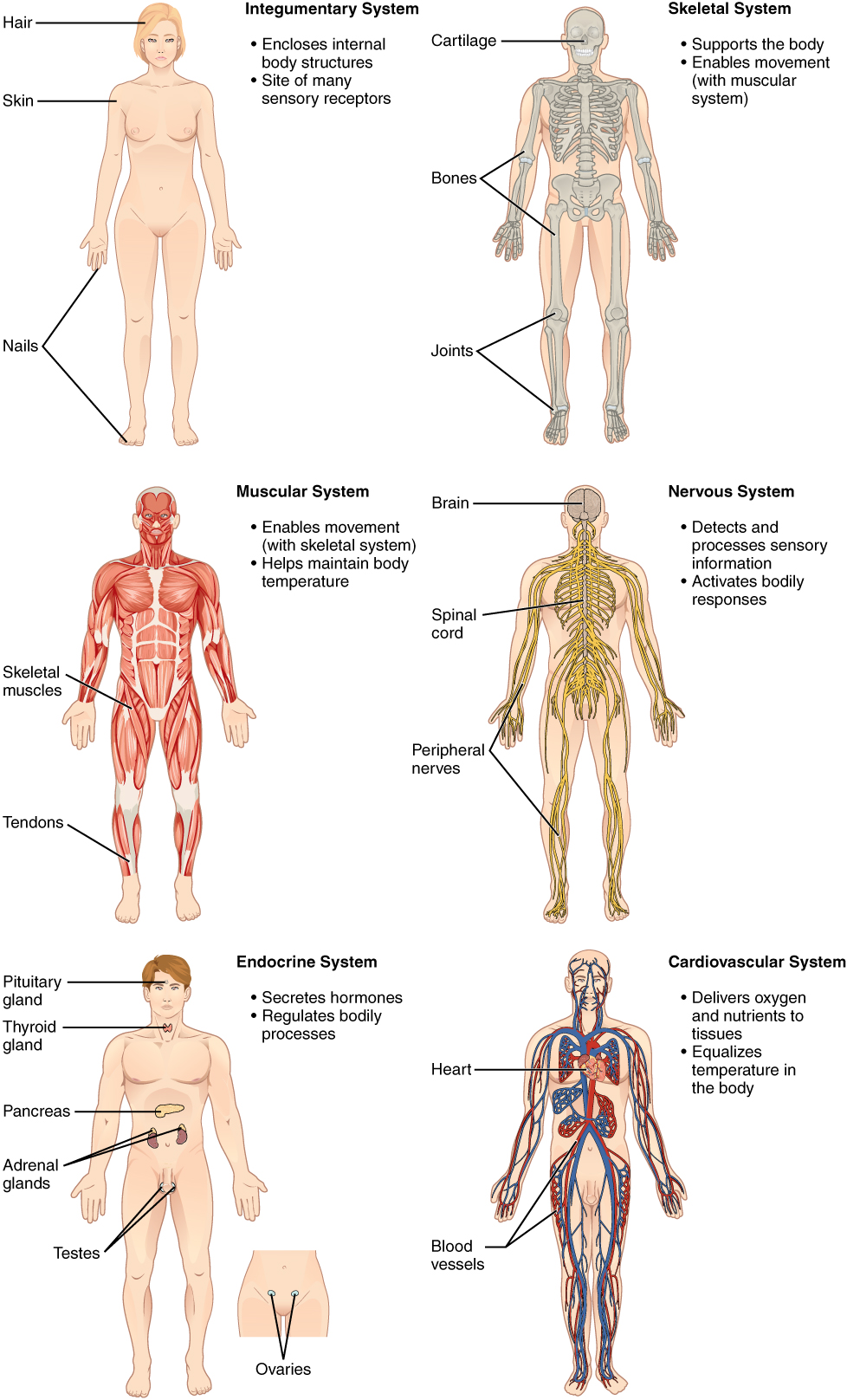

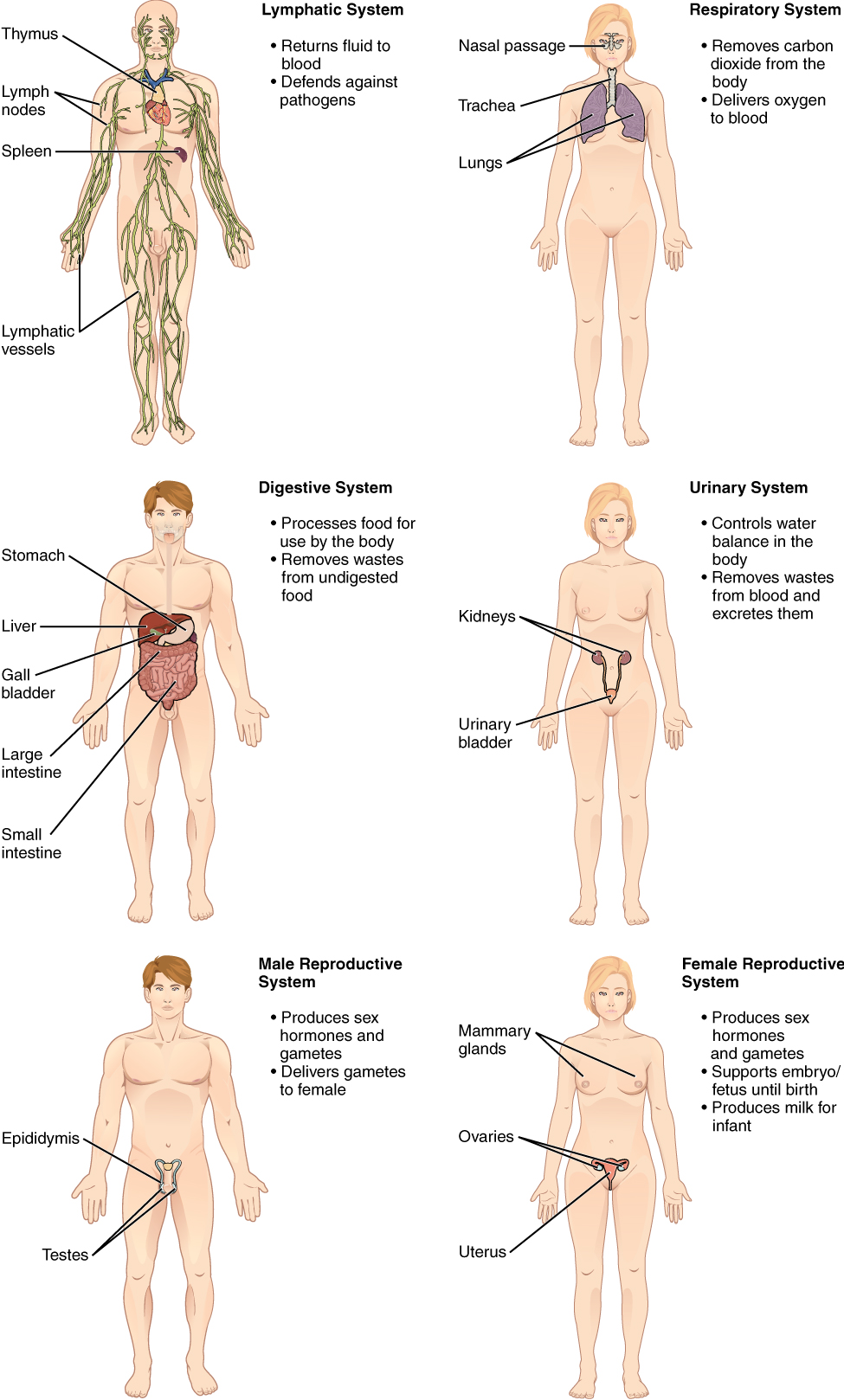

Consider the breakdown into eleven distinct organ systems in the human body (Figure 2.2 and Figure 2.3). Assigning organs to organ systems can be imprecise since organs that “belong” to one system can also have functions integral to another system. In fact, most organs contribute to more than one system.

The organism level is the highest level of organization. An organism is a living being that has a cellular structure and that can independently perform all physiologic functions necessary for life. In multicellular organisms, including humans, all cells, tissues, organs, and organ systems of the body work together to maintain the life and health of the organism.

Watch this video:

Media 2.1. Introduction to Anatomy & Physiology: Crash Course A&P #1 [Online video]. Copyright 2015 by CrashCourse.

Anatomical Position

Health care providers use terminology for the purpose of precision and to reduce medical errors. For example, is a scar “above the wrist” located on the forearm two or three inches away from the hand? Or is it at the base of the hand? Is it on the palm-side or back-side? By using precise anatomical terminology, we eliminate ambiguity. Anatomical terms derive from ancient Greek and Latin words.

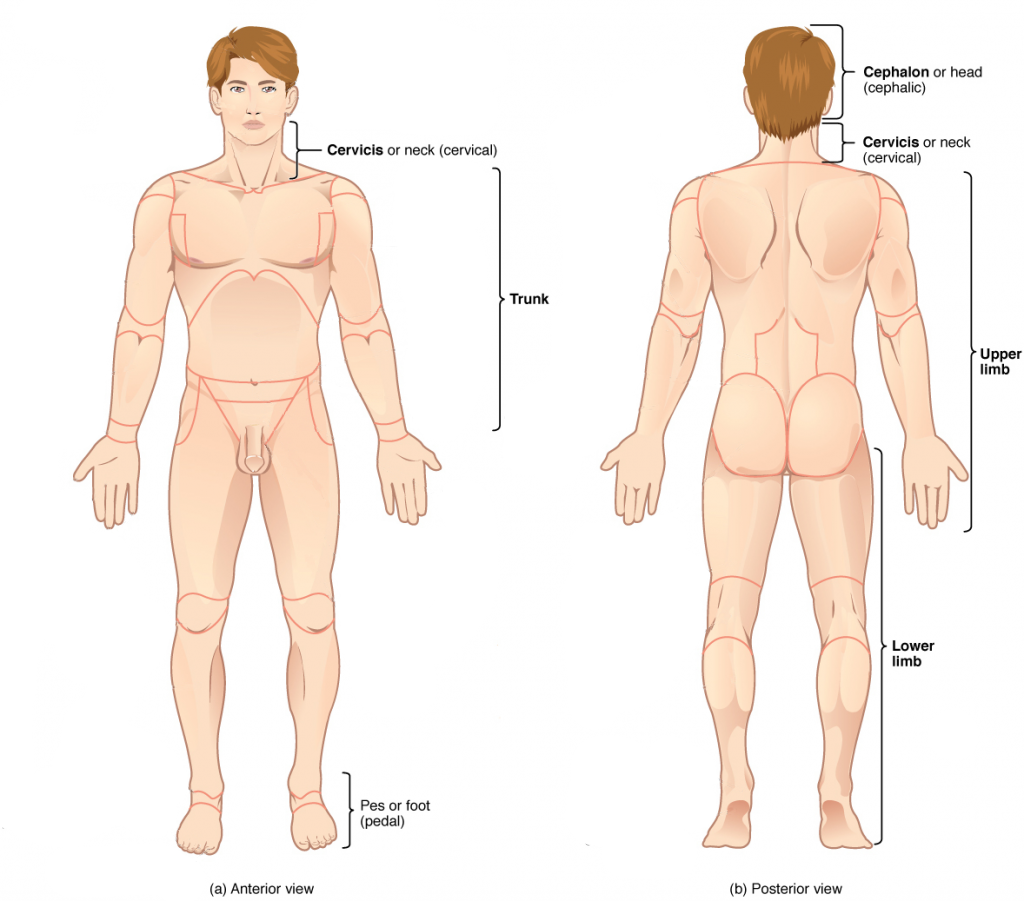

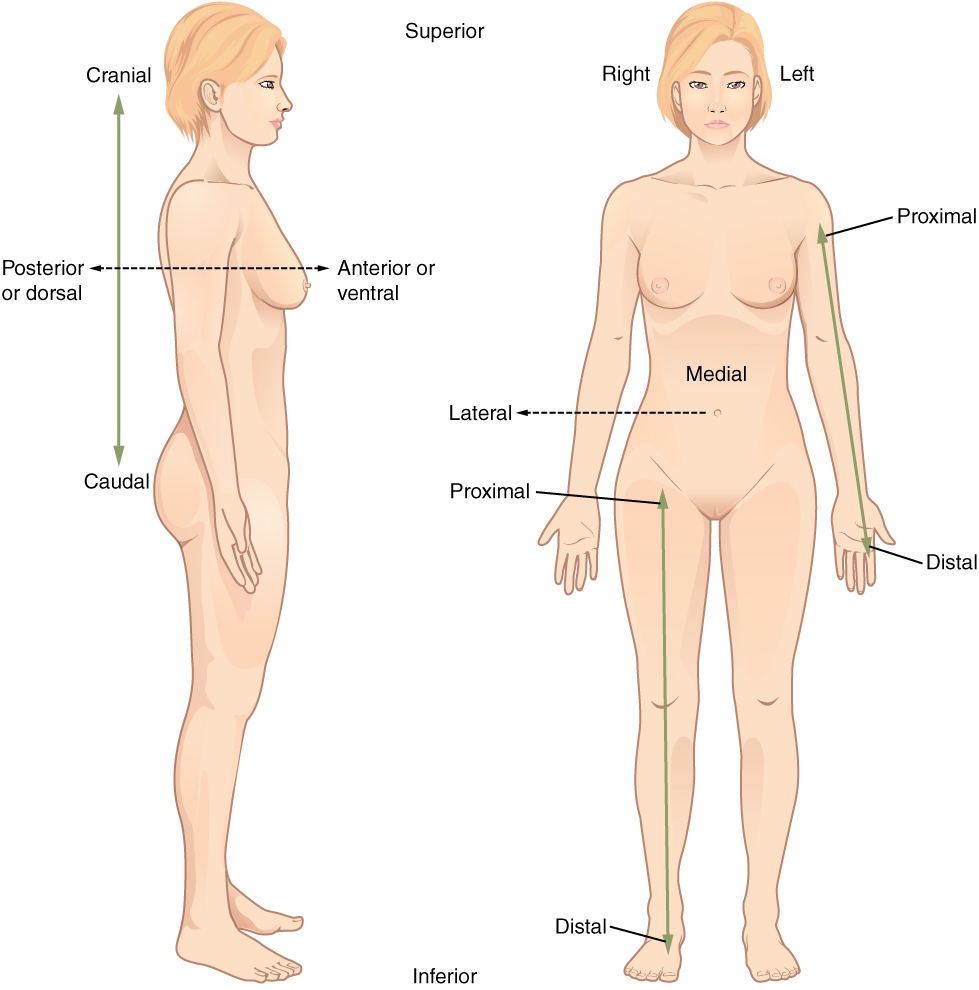

To further increase precision, anatomists standardize the way in which they view the body. Just as maps are normally oriented with north at the top, the standard body “map,” or anatomical position, is that of the body standing upright, with the feet at shoulder width and parallel, toes forward. The upper limbs are held out to each side, and the palms of the hands face forward as illustrated.

Using this standard position reduces confusion. It does not matter how the body being described is oriented, the terms are used as if it is in anatomical position. For example, a scar in the “anterior (front) carpal (wrist) region” would be present on the palm side of the wrist. The term “anterior” would be used even if the hand were palm down on a table.

A body that is lying down is described as either prone or supine. These terms are sometimes used in describing the position of the body during specific physical examinations or surgical procedures.

Regional Terms

The human body’s numerous regions have specific terms to help increase precision. Notice that the term “brachium” or “arm” is reserved for the “upper arm” and “antebrachium” or “forearm” is used rather than “lower arm.” Similarly, “femur” or “thigh” is correct, and “leg” or “crus” is reserved for the portion of the lower limb between the knee and the ankle. You will be able to describe the body’s regions using the terms from the anatomical position.

Directional Terms

Directional terms are essential for describing the relative locations of different body structures. For instance, an anatomist might describe one band of tissue as “inferior to” another or a physician might describe a tumor as “superficial to” a deeper body structure. Commit these terms to memory to avoid confusion when you are studying or describing the locations of particular body parts.

- Anterior (or ventral) describes the front or direction toward the front of the body. The toes are anterior to the foot.

- Posterior (or dorsal) describes the back or direction toward the back of the body. The popliteus is posterior to the patella.

- Superior (or cranial) describes a position above or higher than another part of the body proper. The orbits are superior to the oris.

- Inferior (or caudal) describes a position below or lower than another part of the body proper; near or toward the tail (in humans, the coccyx, or lowest part of the spinal column). The pelvis is inferior to the abdomen.

- Lateral describes the side or direction toward the side of the body. The thumb (pollex) is lateral to the digits.

- Medial describes the middle or direction toward the middle of the body. The hallux is the medial toe.

- Proximal describes a position in a limb that is nearer to the point of attachment or the trunk of the body. The brachium is proximal to the antebrachium.

- Distal describes a position in a limb that is farther from the point of attachment or the trunk of the body. The crus is distal to the femur.

- Superficial describes a position closer to the surface of the body. The skin is superficial to the bones.

- Deep describes a position farther from the surface of the body. The brain is deep to the skull.

Practice these directional terms.

Concept Check

- Find a partner and take turns choosing two body parts on your or your partner’s body.

- Using directional terms, describe the location of those body parts relative to one another.

Body Planes

A section is a two-dimensional surface of a three-dimensional structure that has been cut. Modern medical imaging devices enable clinicians to obtain “virtual sections” of living bodies. We call these scans. Body sections and scans can be correctly interpreted, however, only if the viewer understands the plane along which the section was made. A plane is an imaginary two-dimensional surface that passes through the body. There are three planes commonly referred to in anatomy and medicine:

- The sagittal plane is the plane that divides the body or an organ vertically into right and left sides. If this vertical plane runs directly down the middle of the body, it is called the midsagittal or median plane. If it divides the body into unequal right and left sides, it is called a parasagittal plane or less commonly a longitudinal section.

- The frontal plane is the plane that divides the body or an organ into an anterior (front) portion and a posterior (rear) portion. The frontal plane is often referred to as a coronal plane. (“Corona” is Latin for “crown.”)

- The transverse plane is the plane that divides the body or organ horizontally into upper and lower portions. Transverse planes produce images referred to as cross sections.

Can you locate the planes?

Body Cavities and Serous Membranes

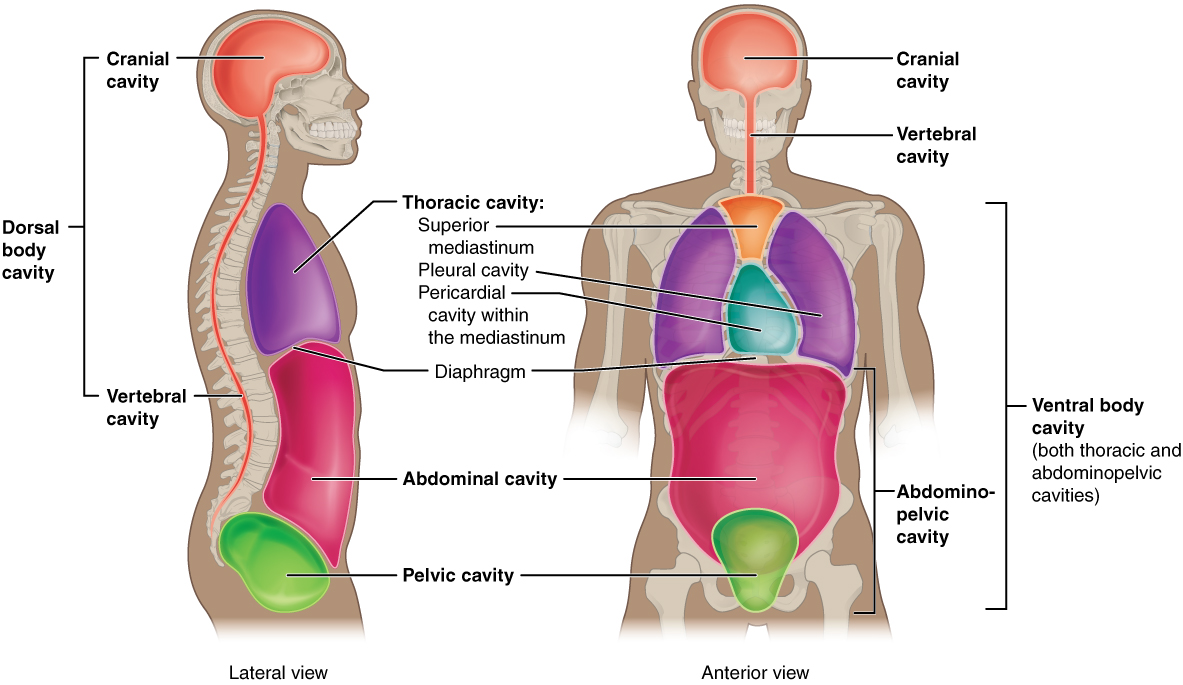

The body maintains its internal organization by means of membranes, sheaths, and other structures that separate compartments. The dorsal (posterior) cavity and the ventral (anterior) cavity are the largest body compartments (Figure 2.6). These cavities contain and protect delicate internal organs, and the ventral cavity allows for significant changes in the size and shape of the organs as they perform their functions. The lungs, heart, stomach, and intestines, for example, can expand and contract without distorting other tissues or disrupting the activity of nearby organs.

Subdivisions of the Posterior (Dorsal) and Anterior (Ventral) Cavities

The posterior (dorsal) and anterior (ventral) cavities are each subdivided into smaller cavities:

The posterior (dorsal) cavity has two main subdivisions:

- In the posterior (dorsal) cavity, the cranial cavity houses the brain

- Protected by the bones of the skulls and cerebrospinal fluid

- The spinal cavity (or vertebral cavity) encloses the spinal cord.

- Protected by the vertebral column and cerebrospinal fluid

The anterior (ventral) cavity has two main subdivisions:

- The thoracic cavity is the more superior subdivision of the anterior cavity, and it is enclosed by the rib cage.

- The thoracic cavity contains the lungs and the heart, which is located in the mediastinum.

- The diaphragm forms the floor of the thoracic cavity and separates it from the more inferior abdominopelvic cavity.

- The abdominopelvic cavity is the largest cavity in the body.

- No membrane physically divides the abdominopelvic cavity.

- The abdominal cavity houses the digestive organs, the pelvic cavity, and the reproductive organs.

Practice locating cavities.

Abdominal Regions and Quadrants

To promote clear communication, for instance about the location of a patient’s abdominal pain or a suspicious mass, health care providers typically divide up the cavity into either nine regions or four quadrants.

Practice locating the quadrants.

Tissue Membranes

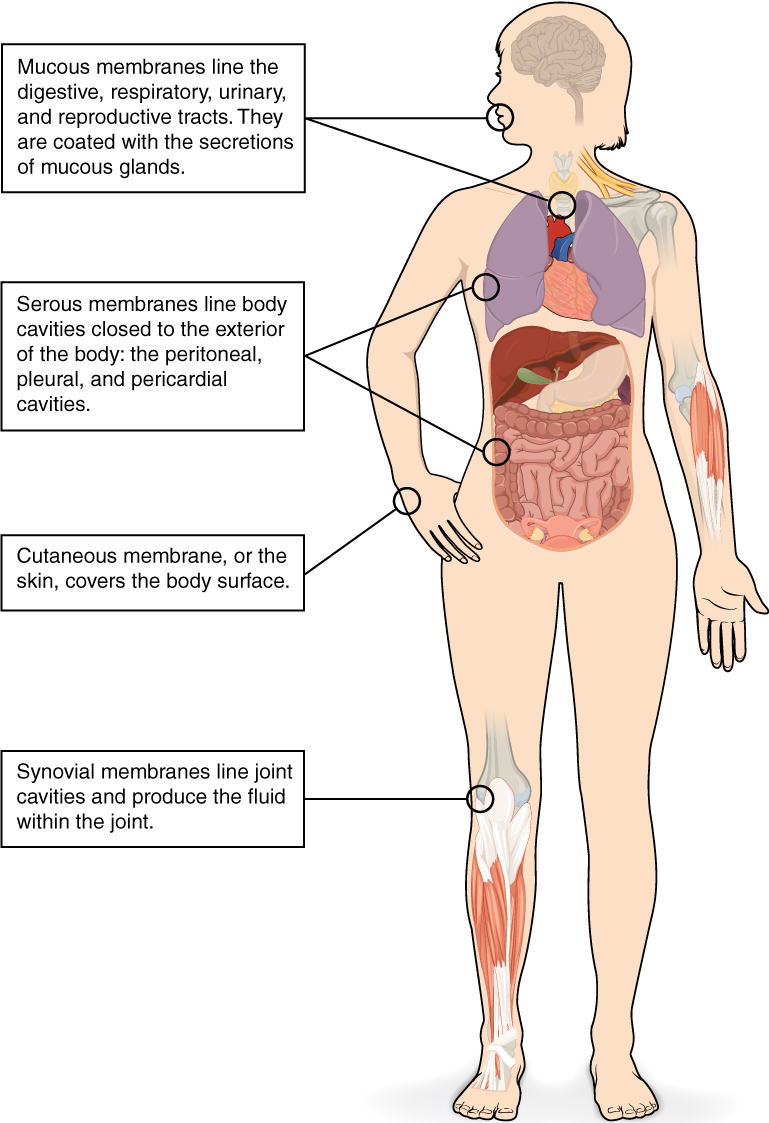

A tissue membrane is a thin layer or sheet of cells that covers the outside of the body (for example, skin), the organs (for example, pericardium), internal passageways that lead to the exterior of the body (for example, abdominal mesenteries), and the lining of the movable joint cavities. There are two basic types of tissue membranes: connective tissue and epithelial membranes (Figure 2.7).

Connective Tissue Membranes

- The connective tissue membrane is formed solely from connective tissue.

- These membranes encapsulate organs, such as the kidneys, and line our movable joints.

- A synovial membrane is a type of connective tissue membrane that lines the cavity of a freely movable joint.

- For example, synovial membranes surround the joints of the shoulder, elbow, and knee.

Epithelial Membranes

- The epithelial membrane is composed of epithelium attached to a layer of connective tissue.

- For example, your skin.

- The mucous membrane is also a composite of connective and epithelial tissues.

- Sometimes called mucosa, these epithelial membranes line the body cavities and hollow passageways that open to the external environment, and include the digestive, respiratory, excretory, and reproductive tracts.

- Mucus, produced by the epithelial exocrine glands, covers the epithelial layer.

- The underlying connective tissue, called the lamina propria (literally “own layer”), help support the fragile epithelial layer.

- The skin is an epithelial membrane also called the cutaneous membrane.

- It is a stratified squamous epithelial membrane resting on top of connective tissue. The apical surface of this membrane is exposed to the external environment and is covered with dead, keratinized cells that help protect the body from desiccation and pathogens.

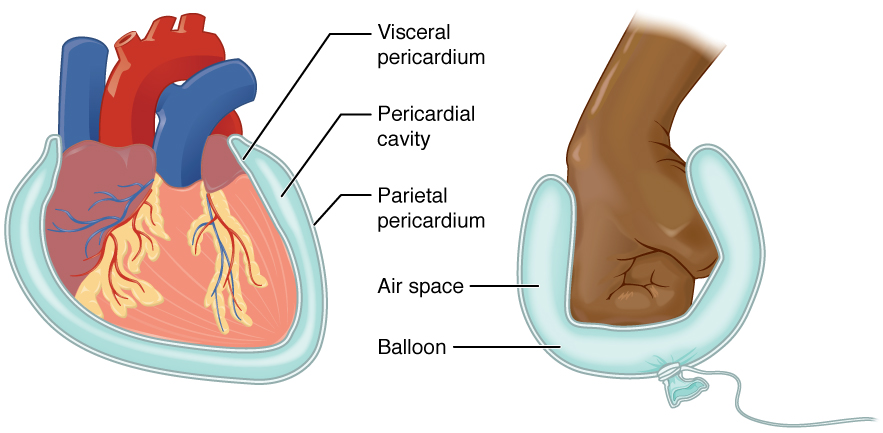

Membranes of the Anterior (Ventral) Body Cavity

- A serous membrane (also referred to as serosa) is an epithelial membrane composed of mesodermally derived epithelium called the mesothelium that is supported by connective tissue.

- Parietal layers: line the walls of the body cavity.

- Visceral layer: covers the organs (the viscera).

- Between the parietal and visceral layers is a very thin, fluid-filled serous space.

There are three serous cavities and their associated membranes. Serous membranes provide additional protection to the viscera they enclose by reducing friction that could lead to inflammation of the organs.

- Pleura: surrounds the lungs in the pleural cavity and reduces friction between the lungs and the body wall.

- Pericardium: surrounds the heart in the pericardial cavity and reduces friction between the heart and the wall of the pericardium.

- Peritoneum: surrounds several organs in the abdominopelvic cavity. The peritoneal cavity reduces friction between the abdominal and pelvic organs and the body wall.

Test Yourself

References

[CrashCourse]. (2015, January 6). Introduction to anatomy & physiology: Crash course A&P #1 [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/uBGl2BujkPQ

Unless otherwise indicated, this chapter contains material adapted from Anatomy and Physiology (on OpenStax), by Betts, et al. and is used under a a CC BY 4.0 international license. Download and access this book for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction.

biological process that results in stable equilibrium

is that of the body standing upright, with the feet at shoulder width and parallel, toes forward. The upper limbs are held out to each side, and the palms of the hands face forward

lying on the abdomen, facing downward

lying on the back, facing upward