Ingredients

Chef Tammy Rink with William R. Thibodeaux and Vicki Mendham

Scaling (weighing) ingredients carefully is very important to the proper outcome of the baked good.

Wheat Flour

- Wheat is by far the most common grain and flour used in the baking industry.

- Wheat flour is the most important ingredient in a bake shop.

- Flours can be produced from cereals, grains, legumes, and other plants for a wide range of uses in baking.

- The function and use of grains and flours in baking varies greatly, depending on the type of flour and its protein and gluten content

- Gluten is an elastic substance made up of proteins in wheat flours.

One of the most important ingredients in the baking process is flour. Almost every item made has some type of flour added. It is the main building block of breads, pastries and most cakes. The production of flour can be traced through the centuries to the beginning of civilization. An important fact for a baker to know is the difference between hard and soft wheat. This gives the baker the ability to know which type of flour to use for the application needed.

There are six different types of wheat grown in North America.

- Hard Red Winter – This versatile wheat can be used in a variety of baking applications as well as making Asian style noodles. The protein content of this milled wheat is between 10 to 15 %. This is a good choice for all purpose flour, hard rolls and flatbreads.

- Hard Red Spring – this wheat has a higher protein content 12 to 18 % and is primarily used to mix into flours. As a standalone flour, it the gluten formed is very strong and often difficult to form into bread. It is often added to improve bread flours and is used in making the high-end breads such as: artisan breads, pizza crust, croissants and rolls.

- Soft Red White – this flour has a weaker gluten formation due to a low protein content of only 8 to 11%. The weaker gluten makes this an excellent wheat for items such as cookies, crackers and pastries.

- Soft White – this a wheat has a low moisture content as well as low protein content 8 to 11 %. It also produces a whiter product, which makes it ideal for cakes, pastries, and some Middle Eastern flatbreads.

- Hard White – this is a newer type of wheat grown in the United States. It is used for making whiter wheat breads as well as Asian noodles, and flatbreads.

- Durum – this is the hardest of all wheats. It has the highest protein content 14 to 16 % as well as the high gluten content. It is primarily used in the production of pastas, couscous and Mediterranean breads.

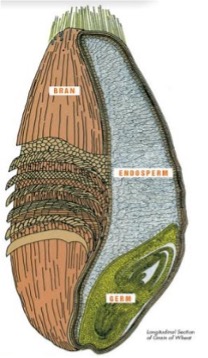

The Wheat Kernel

The wheat kernel is made up of three parts: bran, endosperm, and germ. During the milling process, the kernel is broken up and each part is milled and used.

- Bran – this is the hard outer casing of the kernel. It is darker in color than the inside. When looking at flour the brown specks present is the milled bran. It is removed from white flour. The bran is high in fiber, vitamins, minerals, proteins and fat.

- Germ – this is from where new wheat plants sprout. It has a very high fat content thus is will become rancid quickly. This leads to a very short shelf life of any flour that contains the germ.

- Endosperm – this is the inside part of the kernel. It makes up about 83% of the kernel. This is the part that white flour is derived. It is also the starchiest part of the kernel with about 68 to 76% starch. It contains protein and carbohydrates alone with vitamin B, iron, minerals and soluble fiber.

Milling Process

The purpose for milling to separate the parts of the wheat kernel into usable material. Thus, the endosperm has to be separated from the bran and germ. The endosperm is the part that becomes flour that we use in baking. All parts can be purchased for use in today’s market.

In the early years of milling, the wheat kernels were milled by smashing or rolling them between two large stones. This process gave a course grind to the stone but allowed the parts to be sifted and separated. This was a very laborious process. You can still find stone ground products today in some European markets but most flours in the US are no longer process this way. The most common stone ground products are stone ground grits and cornmeal.

Modern milling of wheat occurs by way of the break system.

Types of Flour used in Bakery

They all affect baked goods in different ways so it is important to choose the correct one.

Cake Flour – this is weak flour made from soft wheat. It is normally pure white. It has a soft and silky feel to it. The gluten and protein formation is low with this flour, which makes it an excellent flour for delicate pastries. Approximately 8% protein

Pastry Flour – a weak flour that is also low in protein and thus low in gluten formation. It is stronger than cake flour however. The color is a creamy yellowish color. Approximately 9% protein

All-purpose – this flour is a general use flour. It can be used in the place of each of the above flour. Its protein content is lower but has enough form a good gluten structure for bread making. Usually this is the home baker’s flour of choice. 10-12% protein

Bread Flour – this is a strong flour made from hard wheat. It offers a good amount of protein and thus offers a good gluten formation. You can purchase this bleached or unbleached. This type is usually reserved for commercial bakeries. 13-17% protein

High-Gluten – We use this flour in class. It is a high protein flour that offers a good gluten formation also.

Self-rising – this flour has the leavener added to it. Baking powder and salt. This is not used in the professional kitchen. Leavener tend to weaken over time so this can be an issue also when scaling recipes most have a leavener added and the amounts vary so not enough could ruin the product. Typically use 1 Cup AP flour and mix in 1 1/2 tsp baking powder and 1/2 teaspoon salt to make your own.

Flour forms the foundation for bread, cakes, and pastries. It may be described as the skeleton, which supports the other ingredients in a baked product. This applies to both yeast and chemically leavened products.

The strength of flour is represented in protein (gluten) quality and quantity. This varies greatly from flour to flour. The quality of the protein indicates the strength and stability of the flour, and the result in bread making depends on the method used to develop the gluten by proper handling during the fermentation. Gluten is a rubber-like substance that is formed by mixing flour with water. Before it is mixed it contains two proteins. Although we use the terms protein and gluten interchangeably, gluten only develops once the flour is moistened and mixed. The protein in the flour becomes gluten.

Hard spring wheat flours are considered the best for bread making as they have a larger percentage of good quality gluten than soft wheat flours. It is not an uncommon practice for mills to blend hard spring wheat with hard winter wheat for the purpose of producing flour that combines the qualities of both. Good bread flour should have about 13% gluten.

Storing Flour

Flour should be kept in a dry, well-ventilated storeroom at a fairly uniform temperature. A temperature of about 21°C (70°F) with a relative humidity of 60% is considered ideal. Flour should never be stored in a damp place. Moist storerooms with temperatures greater than 23°C (74°F) are conducive to mold growth, bacterial development, and rapid deterioration of the flour. A well-ventilated storage room is necessary because flour absorbs and retains odors. For this reason, flour should not be stored in the same place as onions, garlic, coffee, or cheese, all of which give off strong odors.

Hard wheat flour absorbs more liquid than soft flour. Good hard wheat flour should feel somewhat granular when rubbed between the thumb and fingers. A soft, smooth feeling indicates a soft wheat flour or a blend of soft and hard wheat flour. Another indicator is that hard wheat flour retains its form when pressed in the hollow of the hand and falls apart readily when touched. Soft wheat flour tends to remain lumped together after pressure.

Baking Quality

The final and conclusive test of any flour is the kind of bread that can be made from it. The baking test enables the baker to check on the completed loaf that can be expected from any given flour. Good volume is related to good quality gluten; poor volume to young or green flour. Flour that lacks stability or power to hold during the entire fermentation may result in small, flat bread. Flour of this type may sometimes respond to an increase in the amount of yeast. More yeast shortens the fermentation time and keeps the dough in better condition during the pan fermentation period.

Rye Flour

Rye is a hardy cereal grass cultivated for its grain. Its use by humans can be traced back over 2,000 years. Once a staple food in Scandinavia and Eastern Europe, rye declined in popularity as wheat became more available through world trade. A crop well suited to northern climates, rye is grown on the Canadian Prairies and in the northern states such as the Dakotas and Wisconsin.

Rye flour is the only flour other than wheat that can be used without blending (with wheat flour) to make yeast-raised breads. Nutritionally, it is a grain comparable in value to wheat. In some cases, for example, its lysine content (an amino acid), is even biologically superior.

The brown grain is cleaned, tempered, and milled much like wheat grain. One difference is that the rye endosperm is soft and breaks down into flour much quicker that wheat. As a result, it does not yield semolina, so purifiers are seldom used. The bran is separated from the flour by the break roller, and the flour is further rolled and sifted while being graded into chop, meal, light flour, medium flour, and dark flour:.

- Chop: This is the miller’s name for the coarse stock after grinding in a break roller mill.

- Meal: Like chop, meal is made of 100% extraction obtained by grinding the entire rye kernel.

- Light rye flour: This is obtained from the centre of the rye kernel and is low in protein and high in starch content. It can be compared to white bread flour and is used to make light rye breads.

- Medium rye flour: This is straight flour and consists of all the kernels after the bran and shorts have been removed. It is light grey in color, has an ash content of 1%, and is used for a variety of sourdough breads.

- Dark rye flour: This is comparable to first clear wheat flour. It has an ash content of 2% and a protein content of 16%. It is used primarily for heavier types of rye bread.

The lighter rye flours are generally bleached, usually with a chlorine treatment. The purpose of bleaching is to lighten the color, since there is no improvement on the gluten capability of the flour.

Several other types of grains are commonly used in baking. In particular, corn and oats feature predominantly in certain types of baking (quick breads and cookies respectively, for instance) but increasingly rice flour is being used in baked goods, particularly for people with gluten sensitivities or intolerances. The trend to whole grains and the influence of different ethnic cultures has also meant the increase in the use of other grains and pulses for flours used in breads and baking in general.

Corn

Corn is one of the most widely used grains in the world, and not only for baking. Corn in used in breads and cereals, but also to produce sugars (such as dextrose and corn syrup), starch, plastics, adhesives, fuel (ethanol), and alcohol (bourbon and other whisky). It is produced from the maize plant (the preferred scientific and formal name of the plant that we call corn in North America). There are different varieties of corn, some of which are soft and sweet (corn you use for eating fresh or for cooking) and some of which are starchy and are generally dried to use for baking, animal feed, and popcorn.

Corn Varieties Used in Baking

- Cornmeal has a sandy texture and is ground to fine, medium, and coarse consistencies. It has most of the husk and germ removed, and is used is recipes from the American South (e.g., cornbread) and can be used to add texture to other types of breads and pastry.

- Stone-ground cornmeal has a texture not unlike whole wheat flour, as it contains some of the husk and germ. Stone ground cornmeal has more, but it is also more perishable. In baking, it acts more like cake flour due to the lack of gluten.

- Corn flour in North America is very finely ground cornmeal that has had the husk and germ removed. It has a very soft powdery texture. In the U.K. and Australia, corn flour refers to cornstarch.

- Cornstarch is the starch extracted from the maize kernel. It is primarily used as a thickener in baking and other cooking. Cornstarch has a very fine powdery consistency, and can be dissolved easily in water. As a thickening agent, it requires heat to set, and will produce products with a shiny, clear consistency.

- Blue cornmeal has a light blue or violet color and is produced from whole kernels of blue corn. It is most similar to stone-ground cornmeal and has a slightly sweet flavor.

Rice

Rice is another of the world’s most widely used cereal crops and forms the staple for much of the world’s diet. Because rice is not grown in Canada, it is not regulated by the Canadian Grain Commission.

Rice Varieties Used in Baking

- Rice flour is prepared from finely ground rice that has had the husks removed. It has a fine, slightly sandy texture, and provides crispness while remaining tender due to its lack of gluten. For this reason, many gluten-free breads are based on rice flours or blends that contain rice flour.

- Short grain or pearl rice is also used in the pastry shop to produce rice pudding and other desserts.

Oats

Oats are widely used for animal feed and food production, as well as for making breads, cookies, and dessert toppings. Oats add texture to baked goods and desserts.

Oat Varieties Used in Baking

- Bakers will most often encounter rolled oats, which are produced by pressing the de-husked whole kernels through rollers.

- Oat bran and oat flour are produced by grinding the oat kernels and separating out the bran and endosperm.

- Whole grain oat flour is produced by grinding the whole kernel but leaving the ground flour intact.

- Steel-cut oats are more commonly used in cooking and making breakfast cereals, and are the chopped oat kernels.

Other Grains and Pulses

A wide range of additional flours and grains that are used in ethnic cooking and baking are becoming more and more widely available in Canada. These may be produced from grains (such as kamut, spelt, and quinoa), pulses (such as lentils and chickpeas), and other crops (such as buckwheat) that have a grain-like consistency when dried. Increasingly, with allergies and intolerances on the rise, these flours are being used in bakeshops as alternatives to wheat-based products for customers with special dietary needs. (For more on this topic, see the chapter Special Diets, Allergies, Intolerances, Emergent Issues, and Trends in the open textbook Nutrition and Labelling for the Canadian Baker.)

Meals

Corn meal – this is made from the endosperm of the corn kernel. It can be purchased in a variety of styles. It contains no gluten.

Nut meals – various nuts are ground into “flours” that can be used in baking. Almond and Hazelnut are the two most common. These also contain no gluten due to the absent of wheat in the product.

Gluten Free Flours

A wide variety of gluten-free alternatives to regular or wheat flour exist for people with celiac disease, gluten sensitivity or those avoiding gluten for other reasons.

Many gluten-free flours require recipe adjustments or combinations of different types of gluten-free flours to create a good end product. Be sure to evaluate your recipe. There are also many pre-blended gluten flours that you can buy. Be sure to test your recipes to make sure they work in that product.

Here is a list of gluten free “flours (not all inclusive):

- Almond or Walnut

- Garbanzo Bean Flour (chickpea)

- Buckwheat flour

- Arrowroot Flour

- Oat Flour

- Corn Flour

- Coconut Flour

- Tapioca Flour

- Potato Flour

- Rice Flour

Sweeteners

- Sugar comes from a variety of sources. Our primary sugar, sucrose, comes from two sources: sugar cane and sugar beet, but both these sugars are chemically identical.

- As a food item, sugars are classed as carbohydrates, being formed from carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen atoms.

- There are three types of sugar, two of which are most important in their applications for the baker: monosaccharides (simple sugars) and disaccharides (complex sugars).

- Sugar has a wide range of applications in baking. Sugars contribute to sweetness, tenderness and browning of baked goods.

Sugar – refined graduated sugar is a common item in the bake shop. It is used in almost every recipe as the main sweeter ingredient. It can also act as a tenderizer in products. This has no molasses left in it after refining.

Sugar is hydroscopic which means it absorbs moisture in the air and its surroundings.

Light brown sugar – this is sugar that has not been refined as much. It still has some molasses left in it. This gives it a slight addition of acidity. It will feel a bit wet when touched. When measuring this sugar you want to make sure you pack in into the measuring cup tight. If done correctly it will hold its shape when removed.

Dark Brown Sugar – this is sugar that has the highest amount of molasses left in it during the refining process. This has a slightly higher acid content than light brown sugar.

Molasses – a byproduct from the process of refining sugar. It is a thick darn brown liquid. It added moisture to baked goods helping then stay fresher longer.

Honey – a natural sugar syrup made by bees. The type of honey varies depending on the diet of the bees and the area in which they are kept. It is the only food that does not spoil. It may crystalize as it sits but it can be put into warm water, or heated to melt the crystals.

Invert Sugars – these are liquid sugars that are used in the baking kitchen. They can be added to recipes as sweeteners, or used to prevent crystallization of the granulated sugar. Corn syrup and glucose are two of the most common we use.

Fats

- Fats and oils are manufactured and selected by the baker on the basis of certain functions or special characteristics.

- Fats and oils used in baking are made from animal and vegetable sources, with the trend toward vegetable sources.

- Fats and oils form one of the three major food groups and are concentrated energy sources.

- The major categories of fat used by the baker are:

- Butter

- Margarine

- Regular shortenings

- Hydrogenated shortenings

- The functions of fat in baking are:

- Shortening/Tenderizing

- Lubrication

- Lamination

- Creaming

- Moistening

- Add richness

- Increases keeping quality

- Flakiness

- Assists in leavening

- Browning

- Flavor

- Deep-frying

Butter – is made from the processing of heavy cream. As the cream is agitated, the fat molecules pull together and separates from the whey. It can be purchased in stores salted and unsalted. In the kitchen, unsalted butter is preferred so that salt can be measure into the recipes in the correct amounts. Butter will become solid when cold but soft at room temperature. It also has a very low melting point (90 to 95oF).

Margarine – This is a fabricated product from hydrogenated animal and vegetable fats. It also contains flavorings, emulsifiers and dyes to give it color. There are different types that can be purchase. It is cheaper than butter while still maintaining some flavor of butter.

Shortening

Regular – this is the shortening are referred to as plastic shortenings. They have a tough waxy texture with small fat particles. They have a good creaming ability and work well in flaky pie doughs because of their texture. Crisco is an example.

High-ratio – they spread easily through a batter. They are creations for use in recipes that have a high ratio of liquid and sugar to flour.

High-ration liquid – they have less hydrogenation which makes them pourable. This add moisture to cakes and batters. It also allows for easy air incorporation, which will give cakes a better rise and texture.

The following summarize the various functions of fat in baking.

Tenderizing Agents

Used in sufficient quantity, fats tend to “shorten” the gluten strands in flour; hence their name: shortenings. Traditionally, the best example of such fat was lard.

Creaming Ability

This refers to the extent to which fat, when beaten with a paddle, will build up a structure of air pockets. This aeration, or creaming ability, is especially important for cake baking; the better the creaming ability, the lighter the cake.

Plastic Range

Plastic range relates to the temperature at which the fatty acid component melts and over which shortening will stay workable and will “stretch” without either cracking (too cold) or softening (too warm). A fat that stays “plastic” over a temperature range of 4°C to 32°C (39°F to 90°F) would be rated as excellent. A dough made with such a fat could be taken from the walk-in cooler to the bench in a hot bakeshop and handled interchangeably. Butter, on the other hand, does not have a good plastic range; it is almost too hard to work at 10°C (50°F) and too soft at 27°C (80°F).

Lubrication

In dough making, the fat portion makes it easier for the gluten network to expand. The dough is also easier to mix and to handle. This characteristic is known as lubrication.

Moistening Ability

Whether in dough or in a cake batter, fat retards drying out. For this purpose, a 100% fat shortening will be superior to either butter or margarine.

Nutrition

As one of the three major food categories, fats provide a very concentrated source of energy. They contain many of the fatty acids essential for health.

Dairy

Milk – this can be purchased in whole, 2 %, low fat, and skim. Each of these describes the amount of fat this is in the product. Milk today is sold as homogenized which means it has been through a process that keeps the fat and liquid from separating.

Heavy Cream – this has a higher percentage of fat in it. It can be used as is or whipped up and sweetened to make whipped cream. As with milk you can buy heavy cream with different fat percentages.

Butter Milk – this is used often in recipes but contains an acid that is countered by the addition of Baking soda.

Evaporated Milk – also known as “pet “milk. Evaporated milk is milk that has a percentage of the water removed. It is sold in cans unrefrigerated due to sterilization.

| Fat Amounts in Various Dairy Products | |

| Whole Milk | 8 % |

| Skim Milk | < 1 % |

| Heavy Cream | 30 % to 40 % |

| Half and Half | 10 % to 18 % |

Cheese in Baking

Cheese is a concentrated dairy product made from fluid milk and is defined as the fresh or matured product obtained by draining the whey after coagulation of casein.

Cheese making consists of four steps:

- Curdling of the milk, either by enzyme (rennet) or by lactic curdling (natural process)

- Draining in which the whey (liquid part) is drained from the curd (firm part)

- Pressing, which determines the shape

- Ripening, in which the rind forms and the curd develops flavor

Cheese can be classified, with some exceptions, into five broad categories, as follows. Examples are given of specific cheeses that may be used in baking.

- Fresh cheese: High moisture content and no ripening characterize these products. Examples: cottage cheese, baker’s cheese, cream cheese, quark, and ricotta.

- Soft cheeses: Usually some rind, but with a soft interior. Example: feta.

- Semi-soft cheeses: Unripened cheeses of various moisture content. Example: mozzarella.

- Firm cheeses: Well-ripened cheese with relatively low moisture content and fairly high fat content. Examples: Swiss, cheddar, brick.

- Hard cheeses: Lengthy aging and very low moisture content. Example: Parmesan.

In baking, cheeses have different functions. Soft cheeses, mixed with other ingredients, are used in fillings for pastries and coffeecakes. They are used for certain European deep-fried goods, such as cannoli. They may also be used, sometimes in combination with a richer cream cheese, for cheesecakes. All the cheeses itemized under fresh cheese (see above) are all more or less interchangeable for these functions. The coarser cheese may be strained first if necessary. The firmer cheeses are used in products like cheese bread, quiches, pizza, and cheese straws.

A brief description of the cheeses most likely to be used by bakers follows.

Baker’s Cheese

This is a soft, unripened, uncooked cheese. It is made following exactly the same process as for dry curd cottage cheese, up to and including the point when the milk clot is cut into cubes. This cheese is not cooked to remove the whey from the curd. Rather, the curd is drained through cloth bags or it may be pumped through a curd concentrator. The product is then ready to be packaged. The milk fat content is generally about 4%.

Cream Cheese

Cream cheese is a soft, unripened, acid cheese. A milk-and-cream mixture is homogenized and pasteurized, cooled to about 27°C (80°F), and inoculated with lactic-acid-producing bacteria. The resulting curd is not cut, but it is stirred until it is smooth, and then heated to about 50°C (122°F) for one hour. The curd is drained through cloth bags or run through a curd concentrator. Regular cream cheese is fairly high fat, but much lighter versions exist now.

Ricotta

Ricotta is a fresh cheese prepared from either milk or whey that has been heated with an acidulating agent added. Traditionally lemon juice or vinegar was used for acidulation, but in commercial production, a bacterial culture is used. The curds are then strained and the ricotta is used for both sweet and savory applications.

Mascarpone

Mascarpone is a rich, fresh cheese that is a relative of both cream cheese and ricotta cheese. Mascarpone is prepared in a similar fashion to ricotta, but using cream instead of whole milk. The cream is acidified (often by the direct addition of tartaric acid) and heated to a temperature of 85°C (185°F), which results in precipitation of the curd. The curd is then separated from the whey by filtration or mechanical means. The cheese is lightly salted and usually whipped. Note that starter culture and rennet are not used in the production of this type of cheese. The high-fat content and smooth texture of mascarpone cheese make it suitable as a substitute for cream or butter. Ingredient applications of mascarpone cheese tend to focus on desserts. The most famous application of mascarpone cheese is in the Italian dessert tiramisu.

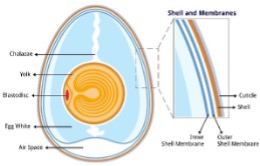

Eggs

The egg is an essential ingredient used in the bake shop. Eggs are essential for structure, color, flavor, nutrition, moisture, shortening effect, leavening and emulsifying of ingredients in baked goods.

The make of the egg is simple – yolk, white and shell. In the diagram you see how each is connected in the shell. The chalazae is the stringy white part you see when you crack the egg. The yolk is high in fat and protein. Lecithin is also found in the yolk and aid in thickening and emulsification of ingredients. The white is the lean part of the egg. It is used for meringues and coagulates when heated.

Grading and Weight of Eggs

The United States grading system for eggs is based on their quality but also size. There are 3 types of grades given to eggs AA, A and B.

| Approximate of Weights of a Large Egg | |

| One whole egg | 1.67 oz. |

| One egg white | 1 oz. |

| One egg yolk | .67 oz. |

| 9 1/2 whole eggs | 1 lb. |

| 16 egg whites | 1 lb. |

| 24 yolks | 1 lb. |

Yeast

Yeast is a microscopic unicellular fungus that multiplies by budding, and under suitable conditions, causes fermentation. Cultivated yeast is widely used in the baking and distilling industries. History tells us that the early Chaldeans, Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans made leavened bread from fermented doughs. This kind of fermentation, however, was not always reliable and easy to control. It was Louis Pasteur, a French scientist who lived in the 19th century, who laid the foundation for the modern commercial production of yeast as we know it today through his research and discoveries regarding the cause and prevention of disease.

The leavening agent in yeast doughs. It is a single cell fungi however there are many species and well as types. When fed the yeast will produce carbon dioxide and alcohol.

Types of Yeast

Wild Yeast

Wild yeast spores are found floating on dust particles in the air, in flour, on the outside of fruits, etc. Wild yeasts form spores faster than cultivated yeasts, but they are inconsistent and are not satisfactory for controlled fermentation purposes.

Compressed Yeast

Fresh or Cake – this is sold in bricks similar to butter. It is moist and perishable. If treated properly it will last about 2 week in the refrigerator. It can be froze to extend the life if not used right away.

Compressed yeast is made by cultivating a select variety, which is known by experiment to produce a yeast that is hardy, consistent, and produces a fermentation with strong enzymatic action. These plants are carefully isolated in a sterile environment free of any other type of yeast and cultivated on a plate containing nutrient agar or gelatin. Wort, a combination of sterilized and purified molasses or malt, nitrogenous matter, and mineral salts is used to supply the food that the growing yeast plants need to make up the bulk of compressed yeast.

After growing to maturity in the fermentation tank, the yeast is separated from the used food or wort by means of centrifugal machines. The yeast is then cooled, filtered, pressed, cut, wrapped, and refrigerated. It is marketed in 454 g (1 lb.) blocks, or in large 20 kg (45 lb.) bags for wholesale bakeries.

Active Dry Yeast

Active Dry – this must be rehydrated with warm water that is 4 times its weight. Yeast will die if the water temperature is 140oF or higher. Major issue with this yeast is that many of the yeast cells in the packet are dead and activating the rest can be problematic.

Active dry yeast is made from a different strain than compressed yeast. The manufacturing process is the same except that the cultivated yeast is mixed with starch or other absorbents and dehydrated. Its production began after World War II, and it was used mainly by the armed forces, homemakers, and in areas where fresh yeast was not readily available.

Even though it is a dry product, it is alive and should be refrigerated below 7°C (45°F) in a closed container for best results. It has a moisture content of about 7%. Storage without refrigeration is satisfactory only for a limited period of time. If no refrigeration is available, the yeast should be kept unopened in a cool, dry place. It should be allowed to warm up to room temperature slowly before being used.

Dry yeast must be hydrated for about 15 minutes in water at least four times its weight at a temperature between 42°C and 44°C (108°F and 112°F). The temperature should never be lower than 30°C (86°F), and dry yeast should never be used before it is completely dissolved.

It takes about 550 g (20 oz.) of dry yeast to replace 1 kg (2.2 lb.) of compressed yeast, and for each kilogram of dry yeast used, an additional kilogram of water should be added to the mix. This product is hardly, if ever, used by bakers, having been superseded by instant yeast (see below).

Instant Dry Yeast

Instant dry yeast – this yeast does not need to be dissolved in water to use it. It can be added to the dry ingredients and mixed due to its ability to absorb water quickly. This makes it the preferred yeast product of most bakers today.

Unlike instant active dry yeast that must be dissolved in warm water for proper rehydration and activation, instant dry yeast can be added to the dough directly, either by:

- Mixing it with the flour before the water is added

- Adding it after all the ingredients have been mixed for one minute

This yeast can be reconstituted. Some manufacturers call for adding it to five times its weight of water at a temperature of 32°C to 38°C (90°F to 100°F). Most formulas suggest a 1:3 ratio when replacing compressed yeast with instant dry. Others vary slightly, with some having a 1:4 ratio. In rich Danish dough, it takes about 400 g (14 oz.), and in bread dough about 250 g to 300 g (9 oz. to 11 oz.) of instant dry yeast to replace 1 kg (2.2 lb.) of compressed yeast. As well, a little extra water is needed to make up for the moisture in compressed yeast. Precise instructions are included with the package; basically, it amounts to the difference between the weight of compressed yeast that would have been used and the amount of dry yeast used.

Instant dry yeast has a moisture content of about 5% and is packed in vacuum pouches. It has a shelf life of about one year at room temperature without any noticeable change in its gassing activity. After the seal is broken, the content turns into a granular powder, which should be refrigerated and used by its best-before date, as noted on the packaging.

Instant dry yeast is especially useful in areas where compressed yeast is not available. However, in any situation, it is practical to use and has the advantages of taking up less space and having a longer shelf life than compressed yeast.

The Functions of Yeast

Yeast has two primary functions in fermentation:

- To convert sugar into carbon dioxide gas, which lifts and aerates the dough

- To mellow and condition the gluten of the dough so that it will absorb the increasing gases evenly and hold them at the same time

In baked products, yeast increases the volume and improves the flavour, texture, grain, colour, and eating quality. When yeast, water, and flour are mixed together under the right conditions, all the food required for fermentation is present as there is enough soluble protein to build new cells and enough sugar to feed them.

Activity within the yeast cells starts when enzymes in the yeast change complex sugar into invert sugar. The invert sugar is, in turn, absorbed within the yeast cell and converted into carbon dioxide gas and alcohol. Other enzymes in the yeast and flour convert soluble starch into malt sugar, which is converted again by other enzymes into fermentable sugar so that aeration goes on from this continuous production of carbon dioxide.

Proper Handling of Yeast

Compressed yeast ages and weakens gradually even when stored in the refrigerator. Fresh yeast feels moist and firm, and breaks evenly without crumbling. It has a fruity, fresh smell, which changes to a sticky mass with a cheesy odor. It is not always easy to recognize whether or not yeast has lost enough of its strength to affect the fermentation and the eventual outcome of the baked bread, but its working quality definitely depends on the storage conditions, temperature, humidity, and age.

The optimum storage temperature for yeast is −1°C (30°F). At this temperature it is still completely effective for up to two months. Yeast does not freeze at this temperature.

Other guidelines for storing yeast include:

- Rotating it properly and using the older stock first

- Avoiding overheating by spacing it on the shelves in the refrigerator

Yeast needs to breathe, since it is a living fungus. The process is continuous, proceeding slowly in the refrigerator and rapidly at the higher temperature in the shop. When respiration occurs without food, the yeast cells starve, weaken, and gradually die.

Yeast that has been frozen and thawed does not keep and should be used immediately. Freezing temperatures weaken yeast, and thawed yeast cannot be refrozen successfully.

Many bakers add compressed yeast directly to their dough. A more traditional way to use yeast is to dissolve it in lukewarm water before adding it to the dough. The water should never be higher than 50°C (122°F) because heat destroys yeast cells. In general, salt should not come into direct contact with yeast, as salt dehydrates the yeast. (Table 10 indicates the reaction of yeast at various temperatures.)

It is best to add the dissolved yeast to the flour when the dough is ready for mixing. In this way, the flour is used as a buffer. (Buffers are ingredients that separate or insulate ingredients, which if in too close contact, might start to react prematurely.) In sponges where little or no salt is used, yeast buds quickly and fermentation of the sponge is rapid.

| Temperature | Reaction |

|---|---|

| 60°F–68°F | slow reaction |

| 80°F–85°F | normal reaction |

| 90°F–100°F | fast reaction |

| 138°-140 F | terminal death point |

Never leave compressed yeast out for more than a few minutes. Remove only the amount needed from the refrigerator. Yeast lying around on workbenches at room temperature quickly deteriorates and gives poor results. One solution used by some bakeries to eliminate steps to the fridge is to have a small portable cooler in which to keep the yeast on the bench until it is needed. Yeast must be kept wrapped at all times because if it is exposed to air the edges and the corners will turn brown. This condition is known as air-burn.

Chemical Leaveners

These leaveners work by releasing gases caused by a chemical reaction.

Types of Chemical Leaveners

- Baking Soda – sodium bicarbonate. The reaction for baking soda is done once liquid is added. Products that contain baking soda must be baked as soon as they are assembled. If allowed to sit the chemical reaction will take place and end causing the product to not rise once in the oven. They are generally used when acids are added to a recipe such as molasses, brown sugar, and some fruit juices and cocoa powder.

- Baking Powder – this is a combination of baking soda and an acid. This allows for the majority of the leavening to take place in the oven. Heat is need to leaving products that contain baking powder. The preferred type found in stores and bakeries is double acting baking powder.

Other Leavening Agents

Air can be whipped in a product and will leaven baked goods. Ex. Air in egg whites

Steam-when liquids reach 212 degrees they will give off steam that will leaven baked goods. ex. Steam in a popover or cream puff

Chocolate

- Chocolate making, like sugar refining, takes place mainly in the importing countries. The process is quite detailed. Essentially the beans are broken down into cocoa mass (press cake) and cocoa butter and then reconstituted, along with other ingredients such as milk, sugar, lecithin, and flavor into tailor-made products for the commercial market.

- One exception is compound chocolate, which has another oil substituted for the cocoa butter. It therefore needs no tempering, which real chocolate does. This is the most popular chocolate product used by bakers for regular bakery work.

- One product, after most of the cocoa butter is extruded, is cocoa powder. Dutch process cocoa powder is made when the normally acidic cocoa mass is made slightly alkaline. Cocoa powder may come sweetened.

- The “stickiness” of chocolate varies with the intended purpose. This is called its viscosity. Chocolate should be stored at about 20°C (68°F) in a clean area free from foreign odors.

True chocolate contains cocoa butter. The main types of chocolate, in decreasing order of cocoa liquor content, are:

- Unsweetened (bitter) chocolate

- Dark chocolate

- Milk chocolate

- White chocolate

Unsweetened Chocolate

Unsweetened chocolate, also known as bitter chocolate, baking chocolate, or cooking chocolate, is pure cocoa liquor mixed with some form of fat to produce a solid substance. The pure ground, roasted cocoa beans impart a strong, deep chocolate flavour. With the addition of sugar in recipes, however, it is used as the base for cakes, brownies, confections, and cookies.

Dark (Sweet, Semi-Sweet, Bittersweet) Chocolate

Dark chocolate has an ideal balance of cocoa liquor, cocoa butter, and sugar. Thus it has the attractive, rich colour and flavour so typical of chocolate, and is also sweet enough to be palatable. It does not contain any milk solids. It can be eaten as is or used in baking. Its flavour does not get lost or overwhelmed, as in many cases when milk chocolate is used. It can be used for fillings, for which more flavourful chocolates with high cocoa percentages ranging from 60% to 99% are often used. Dark is synonymous with semi-sweet, and extra dark with bittersweet, although the ratio of cocoa butter to solids may vary.

- Sweet chocolate has more sugar, sometimes almost equal to cocoa liquor and butter amounts (45% to 55% range).

- Semi-sweet chocolate is frequently used for cooking. It is a dark chocolate with less sugar than sweet chocolate.

- Bittersweet chocolate has less sugar and more liquor than semi-sweet chocolate, but the two are often interchangeable when baking. Bittersweet and semi-sweet chocolates are sometimes referred to as couverture (see below). The higher the percentage of cocoa, the less sweet the chocolate is.

Milk Chocolate

Milk chocolate is solid chocolate made with milk, added in the form of milk powder. Milk chocolate contains a higher percentage of fat (the milk contributes to this) and the melting point is slightly lower. It is used mainly as a flavouring and in the production of candies and moulded pieces.

White Chocolate

The main ingredient in white chocolate is sugar, closely followed by cocoa butter and milk powder. It has no cocoa liquor. It is used mainly as a flavoring in desserts, in the production of candies and, in chunk form in cookies.

Couverture Chocolate

The usual term for top quality chocolate is couverture. Couverture chocolate is a very high-quality chocolate that contains extra cocoa butter. The higher percentage of cocoa butter, combined with proper tempering, gives the chocolate more sheen, firmer “snap” when broken, and a creamy mellow flavor. Dark, milk, and white chocolate can all be made as couvertures.

The total percentage cited on many brands of chocolate is based on some combination of cocoa butter in relation to cocoa liquor. In order to be labelled as couverture by European Union regulations, the product must contain not less than 35% total dry cocoa solids, including not less than 31% cocoa butter and not less than 2.5% of dry non-fat cocoa solids. Couverture is used by professionals for dipping, coating, moulding, and garnishing.

What the percentages don’t tell you is the proportion of cocoa butter to cocoa solids. You can, however, refer to the nutrition label or company information to find the amounts of each. All things being equal, the chocolate with the higher fat content will be the one with more cocoa butter, which contributes to both flavour and mouthfeel. This will also typically be the more expensive chocolate, because cocoa butter is more valuable than cocoa liquor.

But keep in mind that just because two chocolates from different manufacturers have the same percentages, they are not necessarily equal. They could have dramatically differing amounts of cocoa butter and liquor, and dissimilar flavours, and substituting one for the other can have negative effects for your recipe. Determining the amounts of cocoa butter and cocoa liquor will allow you to make informed decisions on chocolate choices.

Cocoa Powder

This is the powder that is left once the cocoa butter has been removed during the production of chocolate.

Types of Cocoa Powder

- Dutch-processed– the acid in this has been neutralized through a washing process. This gives the cocoa powder with a dark color, and smoother flavor.

- Cocoa powder – this is somewhat acidic and lighter in color.

Storing Chocolate

Chocolate will keep for up to a year at a temperature of 18°C to 20°C (64°F to 68°F) with a relative humidity level of 60%. These are the ideal storage conditions. It is not always possible in bakeries to meet the ideal, but in general, room temperature is all right. Chocolate must be kept safe from odors and humidity, and therefore the refrigerator is not the ideal place to store it.

These guidelines apply also to all pure chocolate products, such as chocolate chips, hail, and sticks. All must be protected from humidity and odors and kept cool and dry at room temperature in sealed containers or in the original packaging.

Vanilla

This is the fruit of the orchid plant Vanilla. The fruit is cut, and cured which dries the pod allowing for the intense flavor due to minimal loss of the essential oils.

- Vanilla extract is made from soaking the cut vanilla beans in It is allow to macerate until the desired flavor profile is reached. The beans are then removed and the product is bottle.

- Once you use a bean, it can be dried and used to make vanilla sugar. This is done by enclosing the bean and sugar in a container and allowing the sit. The vanilla flavor is permeate through the sugar.

- Dried Vanilla beans can also be ground and made into vanilla

Salt

Salt has three major functions in baking. It affects:

- Fermentation

- Dough conditioning

- Flavor

Fermentation

Fermentation is salt’s major function:

- Salt slows the rate of fermentation, acting as a healthy check on yeast development.

- Salt prevents the development of any objectionable bacterial action or wild types of fermentation.

- Salt assists in oven browning by controlling the fermentation and therefore lessening the destruction of sugar.

- Salt checks the development of any undesirable or excessive acidity in the dough. It thus protects against undesirable action in the dough and effects the necessary healthy fermentation required to secure a finished product of high quality.

Dough Conditioning

Salt has a binding or strengthening effect on gluten and thereby adds strength to any flour. The additional firmness imparted to the gluten by the salt enables it to hold the water and gas better, and allows the dough to expand without tearing. This influence becomes particularly important when soft water is used for dough mixing and where immature flour must be used. Under both conditions, incorporating a maximum amount of salt will help prevent soft and sticky dough. Although salt has no direct bleaching effect, its action results in a fine-grained loaf of superior texture. This combination of finer grain and thin cell walls gives the crumb of the loaf a whiter appearance.

Salt Flavor

One of the important functions of salt is its ability to improve the taste and flavour of all the foods in which it is used. Salt is one ingredient that makes bread taste so good. Without salt in the dough batch, the resulting bread would be flat and insipid. The extra palatability brought about by the presence of salt is only partly due to the actual taste of the salt itself. Salt has the peculiar ability to intensify the flavour created in bread as a result of yeast action on the other ingredients in the loaf. It brings out the characteristic taste and flavour of bread and, indeed, of all foods. Improved palatability in turn promotes the digestibility of food, so it can be said that salt enhances the nutritive value of bakery products. The lack of salt or too much of it is the first thing noticed when tasting bread. In some bread 2% can produce a decidedly salty taste, while in others the same amount gives a good taste. The difference is often due to the mineralization of the water used in the dough.

Flavorings in Baking

Flavors cannot be considered a truly basic ingredient in bakery products but are important in producing the most desirable products. Flavoring materials consist of:

- Extracts or essences

- Emulsions

- Aromas

- Spices

Note: Salt may also be classed as a flavoring material because it intensifies other flavors.

These and others (such as chocolate) enable the baker to produce a wide variety of attractively flavored pastries, cakes, and other bakery products. Flavor extracts, essences, emulsions, and aromas are all solutions of flavor mixed with a solvent, often ethyl alcohol.

The flavors used to make extracts and essences are the extracted essential oils from fruits, herbs, and vegetables, or an imitation of the same. Many fruit flavours are obtained from the natural parts (e.g., rind of lemons and oranges or the exterior fruit pulp of apricots and peaches). In some cases, artificial flavour is added to enhance the taste, and artificial coloring may be added for eye appeal. Both the Canadian and U.S. departments that regulate food restrict these and other additives. The flavors are sometimes encapsulated in corn syrup and emulsifiers. They may also be coated with gum to preserve the flavor compounds and give longer shelf life to the product. Some of the most popular essences are compounded from both natural and artificial sources. These essences have the true taste of the natural flavors.

Aromas are flavors that have an oil extract base. They are usually much more expensive than alcoholic extracts but purer and finer in their aromatic composition. Aromas are used for flavoring delicate creams, sauces, and ice creams.

Emulsions are homogenized mixtures of aromatic oils and water plus a stabilizing agent (e.g., vegetable gum). Emulsions are more concentrated than extracts and are less susceptible to losing their flavor in the oven. They can therefore be used more sparingly.

Alcohol itself does not contribute to the flavor of foods; only the main flavor component of the liquors or liqueurs does. Care should be taken to evaporate the alcohol fully or it may leave a bitter aftertaste in the dish.

Many bakers and pastry chefs use spirits to impart flavor. Two categories are of interest to the pastry chef: brandies and liqueurs. Their origin, the ingredients used to flavor them if any, the alcohol content, and the sugar content help differentiate these products.

- Brandy usually has an alcohol content ranging from a minimum of 40% to a maximum of 55%. Brandy derives from wine, usually white wine. Another classification of brandies made from fruits other than grapes is called eau-de-vie and includes Calvados (apple), Kirsch (cherry), and Williams (pear).

Liqueurs are mixtures of fine spirits, brandy, sugar, and flavoring. They usually have an alcohol content ranging from 17% to 40% and at least 10% sugar. Because they are volatile substances that vaporize when heated, they should be used mainly for drenching cakes or flavoring creams and icings.

Note: Alcohol content is measured by volume. Water is 0%; pure alcohol is 100%. In the United States, the term proof is used. One degree proof is one-half a degree of alcohol by volume. Thus, 80 proof in the U.S. is equivalent to 40% by volume.

Since flavoring materials have a limited storage life, it is wise to buy a minimum at any one time. Protect all flavors from light and store in airtight containers. Flavorings lose their strength when stored too long. Protect liquid flavor from light, store in amber bottles, and keep bottle tops tight to avoid loss of flavor strength.

Herbs

Herbs tend to be the leaves of fragrant plants that do not have a woody stem. Herbs are available fresh or dried, with fresh herbs having a more subtle flavor than dried. You need to add a larger quantity of fresh herbs (up to 50% more) than dry herbs to get the same desired flavor. Conversely, if a recipe calls for a certain amount of fresh herb, you would use about one-half of that amount of dry herb.

The most common fresh herbs are basil, coriander, marjoram, oregano, parsley, rosemary, sage, tarragon, and thyme. Fresh herbs should have a clean, fresh fragrance and be free of wilted or brown leaves. They can be kept for about five days if sealed inside an airtight plastic bag. Fresh herbs are usually added near the completion of the cooking process so flavors are not lost due to heat exposure.

Dried herbs lose their power rather quickly if not properly stored in airtight containers. They can last up to six months if properly stored. Dried herbs are usually added at the start of the cooking process as their flavor takes longer to develop than fresh herbs.

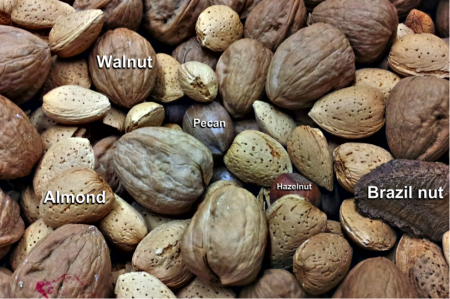

Nuts

Nuts and seeds are nutritious and versatile ingredients. They are used whole, sliced, ground. In combination with sugar and other ingredients they can be used in paste form. Their functions are as ingredients and decorations.

Nuts are a very expensive ingredient in the baking industry and must be handled with care. Bakers require knowledge and understanding of how to use them in recipes and the potential hazards due to allergies. Awareness of cross-contamination is important, as food that should not contain the allergen could become dangerous to eat for those who are allergic.

Allergies are severe adverse reactions that occur when the body’s immune system overreacts to a particular allergen. When someone comes in contact with an allergen, the symptoms of a reaction may develop quickly and rapidly progress from mild to severe.

Peanuts and tree nuts (almonds, Brazil nuts, cashews, hazelnuts, macadamia nuts, pecans, pine nuts, pistachio nuts, and walnuts) fall into the category of the priority food allergens. Note that peanuts are not true nuts; they are from the legume family. However, in some cases people with a tree nut allergy also react to peanuts.

Coconut and nutmeg are not considered tree nuts for the purpose of food allergen labelling in Canada and are not usually restricted from the diet of someone allergic to tree nuts. Coconut is a seed of a fruit and nutmeg is obtained from the seeds of a tropical tree. However, some people react to coconut and nutmeg. People with tree nut allergies should consult their doctor or allergist before trying coconut or nutmeg products.

Due to the severity of nut allergies, any product containing nuts, or that may have come in contact with nuts, should be identified in the bakery, on the package, and on the menu.

The more common types of nuts that are used in the bake shop are listed below.

Coconut

Coconut is the fruit of the coconut palm, consisting of a thick, fibrous brown oval husk under which there is a thin, hard shell enclosing a layer of edible white meat. Ninety-five percent of all commercial coconut grown comes from the Philippines and Sri Lanka. After harvesting, coconuts are shelled, pared, and the white pure coconut meat is washed and pasteurized. The coconut meat is then fed into the shredder. Because of the many uses for the finished product, the meat is cut in different sizes using appropriate cutting heads. Some of these cuts are coarse, medium, macaroon, and extra fine for granulated cuts, and flake, chip, and thread for fancy cuts. In baking, they are used in cookies, colored for decorations, and roasted for coating cakes.

Cashews

Cashews are kidney-shaped nuts that come from a tropical evergreen tree. In baking they are used whole or broken in fruitcakes or sliced and roasted on cakes and fancy pastries.

Walnuts

Walnuts come from a tree native to the temperate parts of the northern hemisphere. They are one of the most widely used nuts in baking, mainly because of their cost. They are halved to serve as decorations on fancy cakes, broken in fruit cakes, or flaked and roasted on the sides of butter cream cakes and fancy pastries.

Hazelnuts or Filberts

Hazelnuts, also called filberts, are the edible nuts of the cultivated European hazel tree, a member of the birch family. They are used for decorations on cakes and pastries, in nougat and praline paste, ground in macaroon-type cookies, or flaked and roasted on the sides of cakes and French pastries. Hazelnuts are the only commercially produced nut in British Columbia.

Almonds

Almonds are nut-like kernels of the small, dry, peach-like fruit of a tree growing in warm regions. Producing countries are Italy, France, Morocco, United States, Portugal, and Australia.

There are two distinct types of almonds: the sweet and the bitter almond. The former are the well-known edible almonds of the world’s market. Sweet almonds are eaten as nuts, or used in confectionery. Like hazlenuts, they are used ground as ingredients, flaked and roasted for decoration, and in paste form. The kernel of the bitter almond is as inedible as peach kernels. When freed from prussic acid, the oil of bitter almond is used in the manufacture of flavouring extracts. Almonds contain about 45% to 50% of a fixed oil.

Peanuts

Peanuts grow in brittle pods, ripening underground and containing one to three edible seeds. Ground or flaked, they are used roasted on the sides of cakes and pastries and as peanut butter in cookies.

Pecans

Pecans come from a North American tree of the walnut family. The edible nut is in a thin, smooth, olive-shaped shell. Fancy halves are used for decorations on cakes and on fruitcakes, or broken in Christmas cake, in pecan rolls made with sweet dough, and in tarts and pies.

Pistachios

Pistachios are the yellow-green seeds from the nut of the pistachio tree, a small tree of the cashew family. This precious nut is mostly used for decorations on fancy cakes and French pastries and for flavouring butter creams and ice creams.

Brazil Nuts

Brazil nuts are hard-shelled, three-sided, oily, edible seeds of a South American tree. They grow in clusters, like segments of an orange, in large, round, hard-shelled fruits. In baking they are used whole in fruitcakes, or flaked and roasted on cakes and pastries.

Chestnuts

Chestnuts are also called maroons. They are not to be confused with the ornamental horse chestnut, which is a different tree. The best quality chestnuts come from Italy and Spain. They are used mainly in ice cream desserts and cooking. Candied sweet chestnuts are called marrons glacés.

Nut Paste and Nut Butters

Nut pastes and butters are used widely in the baking and pastry industry. Pastes are generally products that are finely ground, and contain sugar and other ingredients. Nut butters are produced using primarily the nuts and nut oils, sometimes with sugar and emulsifiers added.

Almond Paste

Almond paste is a fine-ground mixture of half almond and half sugar, or two parts almonds and one part sugar. One type of almond paste is called marzipan. Marzipan is made by an addition of icing sugar, glucose syrup, or egg whites. It is believed that marzipan dates back to AD 24.

At one time, bakers made their own paste, which is a long, tedious job. Since special machines are required to make almond paste economically, it is produced today mainly in large factories.

The paste-making process consists of these steps:

- The almonds are first blanched and then soaked in cold water.

- The almonds are chopped and mixed with the sugar.

- The mixture is ground through a special cylinder-roller machine.

- The creamy mixture is boiled, with more sugar, to dissolve the sugar crystals. The sugar and almonds bind together to form a solid paste. The cooking also sterilizes the almond paste.

Almond paste is usually sold in an airtight container and should be kept in a cool place and properly over-wrapped. If refrigerated, it needs to be protected from humidity. Almond paste may be used for fancy cakes, to mask cakes, and in fillings and fancy cookies. It is considered the most versatile and decorative medium of all.

Working with almond paste requires extreme cleanliness in all parts of production, especially when hand modelling. When modelling, use icing sugar or cornstarch only. Keep free of flour at all times.

Kernel Paste

Kernel paste can serve as a substitute for almond paste. It is made from apricot kernels and peanuts and very few almonds — and therefore it is less expensive than almond paste.

Nougat Paste

Nougat paste, also called hazelnut paste, is made with the finest ingredients, such as hazelnuts and almonds, sugar and vegetable fats, cocoa powder and skim milk powder. Nougat paste is used in butter icing and cookies.

Peanut Butter

Peanut butter is widely used in cookies and other baking, such as fillings and bars. Natural peanut butter contains only peanuts and peanut oil, and may have a small amount of salt added, while processed peanut butters also contain sugar and emulsifiers. Due to allergy concerns, peanut products must always be labelled and handled with care.

Flavorings in Baking

Flavors cannot be considered a truly basic ingredient in bakery products but are important in producing the most desirable products. Flavoring materials consist of:

- Extracts or essences

- Emulsions

- Aromas

- Spices

Note: Salt may also be classed as a flavoring material because it intensifies other flavours.

These and others (such as chocolate) enable the baker to produce a wide variety of attractively flavoured pastries, cakes, and other bakery products. Flavor extracts, essences, emulsions, and aromas are all solutions of flavour mixed with a solvent, often ethyl alcohol.

The flavors used to make extracts and essences are the extracted essential oils from fruits, herbs, and vegetables, or an imitation of the same. Many fruit flavors are obtained from the natural parts (e.g., rind of lemons and oranges or the exterior fruit pulp of apricots and peaches). In some cases, artificial flavor is added to enhance the taste, and artificial coloring may be added for eye appeal. Both the Canadian and U.S. departments that regulate food restrict these and other additives. The flavors are sometimes encapsulated in corn syrup and emulsifiers. They may also be coated with gum to preserve the flavor compounds and give longer shelf life to the product. Some of the most popular essences are compounded from both natural and artificial sources. These essences have the true taste of the natural flavors.

Aromas are flavors that have an oil extract base. They are usually much more expensive than alcoholic extracts but purer and finer in their aromatic composition. Aromas are used for flavoring delicate creams, sauces, and ice creams.

Emulsions are homogenized mixtures of aromatic oils and water plus a stabilizing agent (e.g., vegetable gum). Emulsions are more concentrated than extracts and are less susceptible to losing their flavor in the oven. They can therefore be used more sparingly

Alcohol and Spirits in Baking

Alcohol itself does not contribute to the flavor of foods; only the main flavor component of the liquors or liqueurs does. Care should be taken to evaporate the alcohol fully or it may leave a bitter aftertaste in the dish.

Many bakers and pastry chefs use spirits to impart flavor. Two categories are of interest to the pastry chef: brandies and liqueurs. Their origin, the ingredients used to flavor them if any, the alcohol content, and the sugar content help differentiate these products.

- Brandy usually has an alcohol content ranging from a minimum of 40% to a maximum of 55%. Brandy derives from wine, usually white wine. Another classification of brandies made from fruits other than grapes is called eau-de-vie and includes Calvados (apple), Kirsch (cherry), and Williams (pear).

Liqueurs are mixtures of fine spirits, brandy, sugar, and flavoring. They usually have an alcohol content ranging from 17% to 40% and at least 10% sugar. Because they are volatile substances that vaporize when heated, they should be used mainly for drenching cakes or flavoring creams and icings.

Note: Alcohol content is often measured by volume. Water is 0%; pure alcohol is 100%. In the United States, the term proof is used. One degree proof is one-half a degree of alcohol by volume. Thus, 80 proof in the U.S. is equivalent to 40% by volume.

Since flavoring materials have a limited storage life, it is wise to buy a minimum at any one time. Protect all flavors from light and store in airtight containers. Flavorings lose their strength when stored too long. Protect liquid flavor from light, store in amber bottles, and keep bottle tops tight to avoid loss of flavor strength.

Some ingredients substitutions can be made if you adjust the formula accordingly.