53 The Role of Ethics and National Culture

Author removed at the request of original publisher

Learning Objectives

- Consider the role of ethics in communication.

- Consider the role of national culture on communication.

Ethics and Communication

“People aren’t happy when the unexpected happens, but they are even unhappier if they find out you tried to hide it,” says Bruce Patton, a partner at Boston-based Vantage Partners LLC (Michelman, 2004). To speak or not to speak? One of the most challenging areas of effective business communication occurs in moments of crisis management. But in an age of instant information, the burden on business to speak out quickly and clearly in times of crisis has never been greater.

The alternative to a clear message is seen as a communication blocker, in addition to being guilty of the misdeed, disaster, or infraction at hand. The Exxon Valdez disaster is a classic example of ineffective crisis management and communication. When millions of barrels of oil spilled into Prince William Sound, the company’s poor response only added to the damage. Exxon Mobil Corporation executives refused to acknowledge the extent of the problem and declined to comment on the accident for almost a week. Exxon also sent a succession of lower level spokespeople to deal with the media (Holusha, 1989).

Instead, a more effective method of crisis communication is to have the company’s highest ranking official become the spokesperson who communicates the situation. This is the approach that James Burke, the chairman of Johnson & Johnson Services, Inc., took when tampering was discovered with Tylenol bottles. He became the face of the crisis, communicating with the public and explaining what J & J would do. His forthrightness built trust and allayed customer fears.

Ethical, forthright communication applies inside the company as well as externally with the public. “When the truth is missing, people feel demoralized, less confident, and ultimately are less loyal,” write leadership experts Beverly Kaye and Sharon Jordan-Evans. “Research overwhelmingly supports the notion that engaged employees are ‘in the know.’ They want to be trusted with the truth about the business, including its challenges and downturns” (Kaye & Jordan-Evans, 2008).

Cross-Cultural Communication

Culture is a shared set of beliefs and experiences common to people in a specific setting. The setting that creates a culture can be geographic, religious, or professional. As you might guess, the same individual can be a member of many cultures, all of which may play a part in the interpretation of certain words.

The different and often “multicultural” identity of individuals in the same organization can lead to some unexpected and potentially large miscommunications. For example, during the Cold War, Soviet leader Nikita Khruschev told the American delegation at the United Nations, “We will bury you!” His words were interpreted as a threat of nuclear annihilation. However, a more accurate reading of Khruschev’s words would have been, “We will overtake you!” meaning economic superiority. The words, as well as the fear and suspicion that the West had of the Soviet Union at the time, led to the more alarmist and sinister interpretation (Garner, 2007).

Miscommunications can arise between individuals of the same culture as well. Many words in the English language mean different things to different people. Words can be misunderstood if the sender and receiver do not share common experiences. A sender’s words cannot communicate the desired meaning if the receiver has not had some experience with the objects or concepts the words describe (Effective communication, 2004).

It is particularly important to keep this fact in mind when you are communicating with individuals who may not speak English as a first language. For example, when speaking with nonnative English-speaking colleagues, avoid “isn’t it?” questions. This sentence construction does not exist in many other languages and can be confusing for nonnative English speakers. For example, to the question, “You are coming, aren’t you?” they may answer, “Yes” (I am coming) or “No” (I am coming), depending on how they interpret the question (Lifland, 2006).

Cultures also vary in terms of the desired amount of situational context related to interpreting situations. People in very high context cultures put a high value on establishing relationships prior to working with others and tend to take longer to negotiate deals. Examples of high context cultures include China, Korea, and Japan. Conversely, people in low context cultures “get down to business” and tend to negotiate quickly. Examples of low context cultures include Germany, Scandinavia, and the United States (Hall, 1976; Munter, 1993).

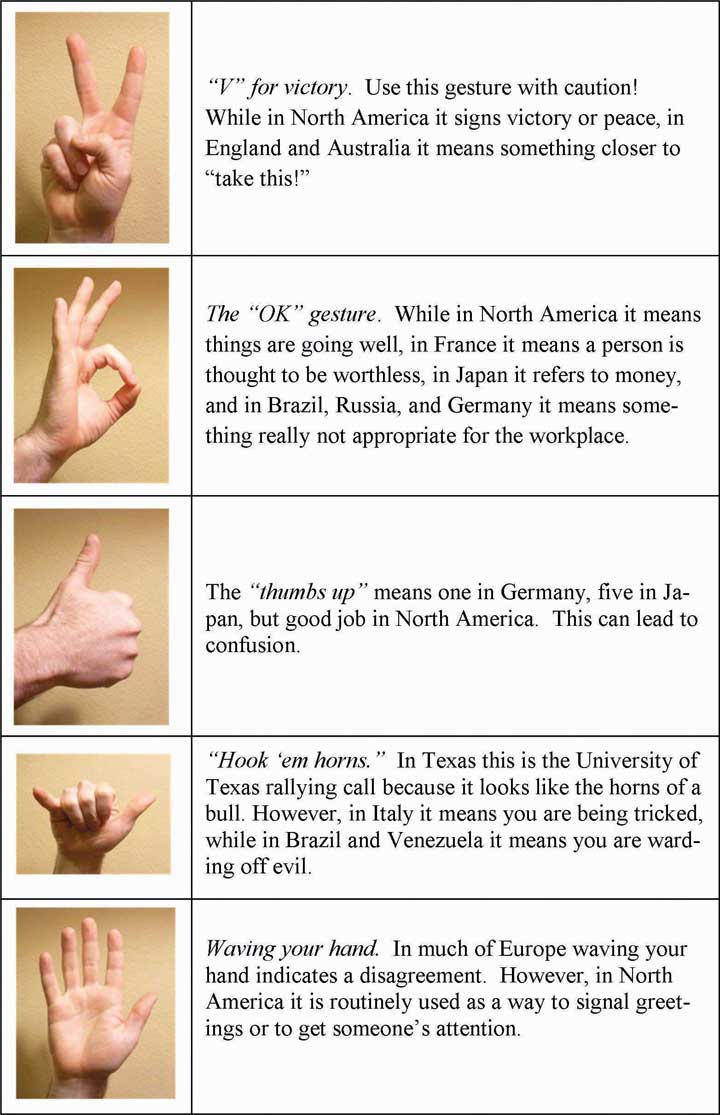

Finally, don’t forget the role of nonverbal communication. As we learned in the nonverbal communication section, in the United States, looking someone in the eye when talking is considered a sign of trustworthiness. In China, by contrast, a lack of eye contact conveys respect. A recruiting agency that places English teachers warns prospective teachers that something that works well in one culture can offend in another: “In Western countries, one expects to maintain eye contact when we talk with people. This is a norm we consider basic and essential. This is not the case among the Chinese. On the contrary, because of the more authoritarian nature of the Chinese society, steady eye contact is viewed as inappropriate, especially when subordinates talk with their superiors” (Chinese culture-differences and taboos, 2009).

It’s easy to see how meaning could become confused, depending on how and when these signals are used. When in doubt, experts recommend that you ask someone around you to help you interpret the meaning of different gestures, that you be sensitive, and that you remain observant when dealing with a culture different from your own.

Key Takeaway

Ethical, forthright communication applies inside a company as well as externally with the public. Trying to cover up or ignore problems has been the downfall of many organizational members. There are differences in word meanings and nonverbal communication. For example, in North America, the nonverbal V means victory or peace, but in Australia means something closer to “take this,” which could still fit if your team wins a championship but probably isn’t exactly what was meant.

Exercises

- How can you assess if you are engaging in ethical communications?

- What experiences have you had with cross-cultural communications? Please share at least one experience when this has gone well and one when it has not gone well.

- What advice would you give to someone who will be managing a new division of a company in another culture in terms of communication?

References

Chinese culture—differences and taboos. (n.d.). Retrieved January 27, 2009, from the Footprints Recruiting Inc. Web site: http://www.footprintsrecruiting.com/content_321.php?abarcar_Session=2284f8a72fa606078aed24b8218f08b9.

Effective communication. (2004, May 31). Retrieved July 2, 2008, from DynamicFlight.com: http://www.dynamicflight.com/avcfibook/communication.

Garner, E. (2007, December 3). Seven barriers to great communication. Retrieved July 2, 2008, from Hodu.com: http://www.hodu.com/barriers.shtml.

Hall, E. (1976). Beyond culture. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Holusha, J. (1989, April 4). Exxon’s public-relations problem. New York Times. Retrieved July 2, 2008, from http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res= 950DE1DA1031F932A15757C0A96F948260.

Kaye, B., & Jordan-Evans, S. (2008, September 11). Tell them the truth. Fast Company. Retrieved January 27, 2009, from http://www.fastcompany.com/resources/talent/bksje/092107-tellthemthetruth.html.

Lifland, S. (2006). Multicultural communication tips. American Management Association. Retrieved July 2, 2008, from http://www.amanet.org/movingahead/editorial.cfm?Ed=37&BNKNAVID=24&display=1.

Michelman, P. (2004, December 13). Sharing news that might be bad. Harvard Business School Working Knowledge Web site. Retrieved July 2, 2008, from http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/4538.html.

Munter, M. (1993). Cross-cultural communication for managers. Business Horizons, 36, 69–78.