Safety

5.3 Safety Strategies

Safety strategies have been developed based on research to reduce the likelihood of errors and to create safe standards of care. Examples of safety initiatives include strategies to prevent medication errors, standardized checklists, and structured team communication tools.

Medication Errors

Several initiatives have been developed nationally to prevent medication errors, such as the establishment of a “Do Not Use List of Abbreviations,” a “List of Error-Prone Abbreviations,” “Frequently Confused Medication List,” “High-Alert Medications List,” and the “Do Not Crush List.” Additionally, it is considered a standard of care for nurses to perform three checks of the rights of medication administration whenever administering medication. View more information about these safety initiatives to prevent medication errors using the hyperlinks provided below. Specific strategies to prevent medication errors are discussed in the “Preventing Medication Errors” of the “Legal/Ethical” chapter of the Open RN Nursing Pharmacology textbook. The rights of medication administration are discussed in the “Basic Concepts of Administering Medications” section of the “Administration of Enteral Medications” chapter of the Open RN Nursing Skills textbook.

Read more about safety initiatives implemented to prevent medication errors using these hyperlinks:

Checklists

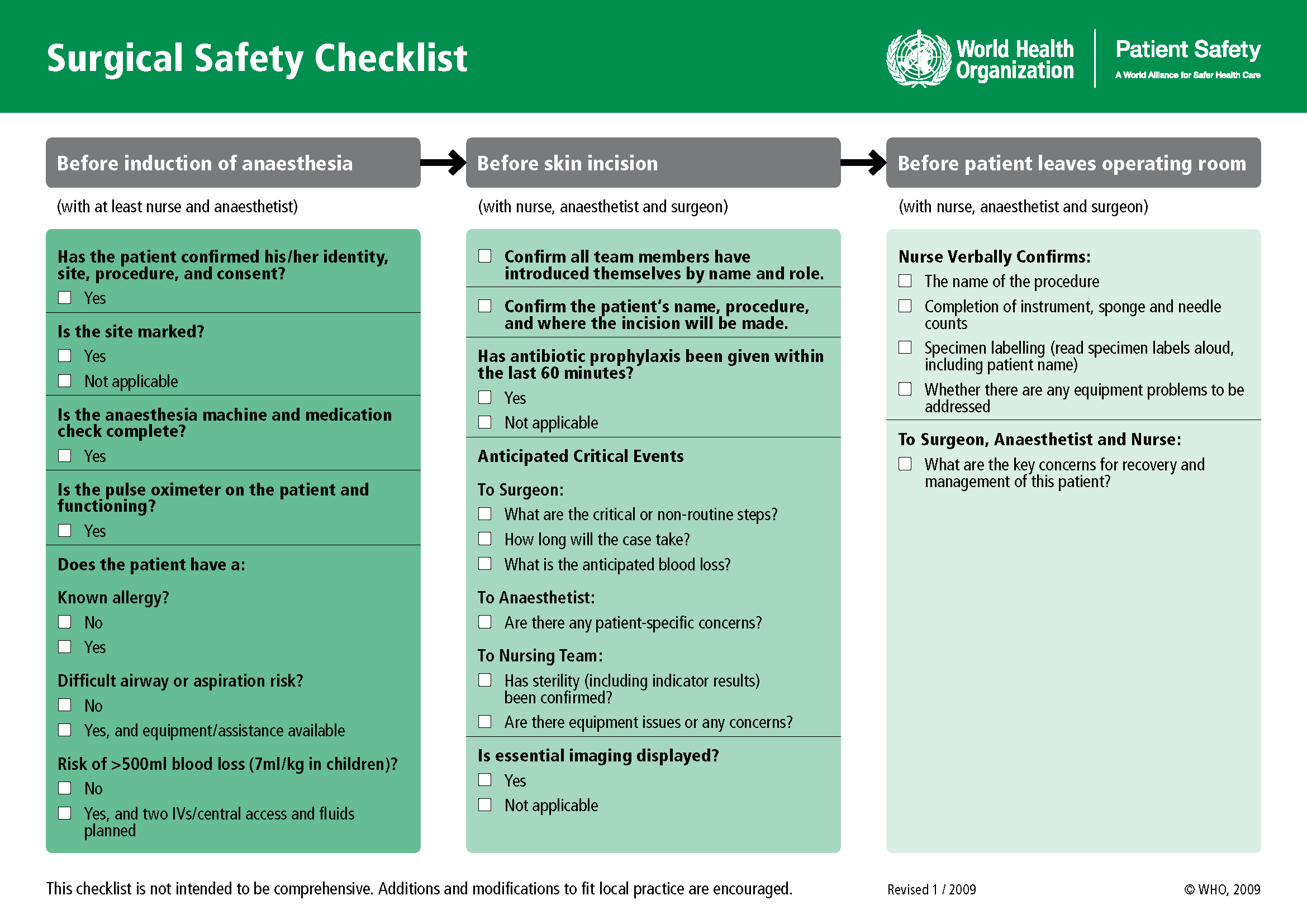

Performance of complex medical procedures is often based on memory, even though humans are prone to short-term memory loss, especially when we are multitasking or under stress. The point-of-care checklist is an example of a patient care safety initiative that reduces this reliance on fallible memory. For example, a surgical checklist developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) has been adopted by most surgical providers around the world as a standard of care. It has significantly decreased injuries and deaths caused by surgeries by focusing on teamwork and communication. The Association of PeriOperative Registered Nurses (AORN) combined recommendations from The Joint Commission and the WHO to create a specific surgical checklist for nurses. See Figure 5.2[1] for an image of the WHO surgical checklist.

Review the AORN Comprehensive Surgical Checklist by the Association of PeriOperative Registered Nurses.

Team Communication

Nurses routinely communicate with multidisciplinary health care team members and contact health care providers to report changes in patient status. Serious patient harm can occur when patient information is absent, incomplete, erroneous, or delayed during team communication. Standardized methods of communication have been developed to ensure that accurate information is exchanged among team members in a structured and concise manner.

ISBARR

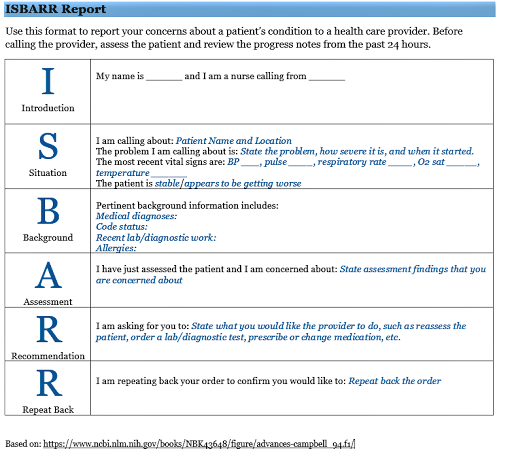

A common format for communication between health care team members is ISBARR, a mnemonic for the components of Introduction, Situation, Background, Assessment, Request/Recommendations, and Repeat back. See Figure 5.3[2] for an image of an ISBARR reference card.

- Introduction: Introduce your name, role, and the agency from which you are calling.

- Situation: Provide the patient’s name and location, why you are calling, recent vital signs, and the status of the patient.

- Background: Provide pertinent background information about the patient such as admitting medical diagnoses, code status, recent relevant lab or diagnostic results, and allergies.

- Assessment: Share abnormal assessment findings and your concerns.

- Request/Recommendations: State what you would like the provider to do, such as reassess the patient, order a lab/diagnostic test, prescribe/change medication, etc.

- Repeat back: If you are receiving new orders from a provider, repeat them to confirm accuracy. Be sure to document communication with the provider in the patient’s chart.

Handoff Reports

Handoff reports are a specific type of team communication as patient care is transferred. Handoff reports are defined by The Joint Commission as, “A transfer and acceptance of patient care responsibility achieved through effective communication. It is a real-time process of passing patient specific information from one caregiver to another, or from one team of caregivers to another, for the purpose of ensuring the continuity and safety of the patient’s care.” Handoff reports occur during multiple stages of patient care, such as between nurses at the end of shifts, when a patient is transferred from one unit to another within a health care agency, or when a patient is transferred to a different facility. In 2017 The Joint Commission issued a sentinel alert about inadequate handoff communication resulting in patient harm such as wrong-site surgeries, delays in treatment, falls, and medication errors. Strategies to improve handoff communication, such as bedside handoff report checklists, have been implemented at agencies across the country.

Bedside handoff reports typically occur between nurses during inpatient care as the off-going and the incoming nurses communicate current, up-to-date details about the patient’s care . The report is optimally conducted at the bedside and includes the patient. Family members may be included during the report with the patient’s permission. See the hyperlink below to view a sample bedside shift report checklist from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Although a bedside handoff report is similar to an ISBARR report, it contains additional information to ensure continuity of care across nursing shifts, such as current head-to-toe assessment findings to establish baseline status; information about equipment such as IVs, catheters, and drainage tubes; and recent changes in medications, lab results, diagnostic tests, and treatments.

View a Bedside Shift Report Checklist from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- "9789241598590_eng_Checklist.pdf" by WHO is in the Public Domain ↵

- "ISBARR Reference Card" by Kim Ernstmeyer at Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

Asking a patient to rate the severity of their pain on a scale from 0 to 10, with “0” being no pain and “10” being the worst pain imaginable is a common question used to screen patients for pain. However, according to The Joint Commission requirements described earlier, this question can be used to initially screen a patient for pain, but a thorough pain assessment is required. Additionally, the patient's comfort-function goal must be assessed. The comfort-function goal provides the basis for the patient's individualized pain treatment plan and is used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions.

PQRSTU, OLDCARTES, and COLDSPA

The “PQRSTU," “OLDCARTES,” or "COLDSPA" mnemonics are helpful in remembering a standardized set of questions used to gather additional data about a patient’s pain. See Figure 11.4[1] for the questions associated with a “PQRSTU” assessment framework. While interviewing a patient about pain, use open-ended questions to allow the patient to elaborate on information that further improves your understanding of their concerns. If their answers do not seem to align, continue to ask focused questions to clarify information. For example, if a patient states that “the pain is tolerable” but also rates the pain as a “7” on a 0-10 pain scale, these answers do not align, and the nurse should continue to use follow-up questions using the PQRSTU framework. Upon further questioning the patient explains they rate the pain as a “7” in their knee when participating in physical therapy exercises, but currently feels the pain is tolerable while resting in bed. This additional information assists the nurse to customize interventions for effective treatment with reduced potential for overmedication with associated side effects.

Sample questions when using the PQRSTU assessment are included in Table 11.3a.

Table 11.3a. Sample PQRSTU Focused Questions for Pain

| PQRSTU | Questions Related to Pain |

|---|---|

| Provocation/Palliation

|

What makes your pain worse?

What makes your pain feel better? |

| Quality

|

What does the pain feel like?

Note: You can provide suggestions for pain characteristics such as “aching,” “stabbing,” or “burning.” |

| Region

|

Where exactly do you feel the pain? Does it move around or radiate elsewhere?

Note: Instruct the patient to point to the pain location. |

| Severity

|

How would you rate your pain on a scale of 0 to 10, with “0” being no pain and “10” being the worst pain you’ve ever experienced? |

| Timing/Treatment

|

When did the pain start?

What were you doing when the pain started? Is the pain constant or does it come and go? If the pain is intermittent, when does it occur? How long does the pain last? Have you taken anything to help relieve the pain? |

| Understanding

|

What do you think is causing the pain? |

An alternative mnemonic to use when assessing pain is “OLDCARTES.”

- Onset: When did the pain start? How long does it last?

- Location: Where is the pain?

- Duration: How long has the pain been going on? How long does an episode last?

- Characteristics: What does the pain feel like? Can the pain be described in terms such as stabbing, gnawing, sharp, dull, aching, piercing, or crushing?

- Aggravating factors: What brings on the pain? What makes the pain worse? Are there triggers such as movement, body position, activity, eating, or the environment?

- Radiating: Does the pain travel to another area or the body, or does it stay in one place?

- Treatment: What has been done to make the pain better and has it been helpful? Examples include medication, position change, rest, and application of hot or cold.

- Effect: What is the effect of the pain on participating in your daily life activities?

- Severity: Rate your pain from 0 to 10.

A third mnemonic used is "COLDSPA."

- C: Character

- O: Onset

- L: Location

- D: Duration

- S: Severity

- P: Pattern

- A: Associated Factors

No matter which mnemonic is used to guide the assessment questions, the goal is to obtain comprehensive assessment data that allows the nurse to create a customized nursing care plan that effectively addresses the patient’s need for comfort.

Pain Scales

In addition to using the PQRSTU or OLDCARTES methods of investigating a patient’s chief complaint, there are several standardized pain rating scales used in nursing practice.

FACES Scale

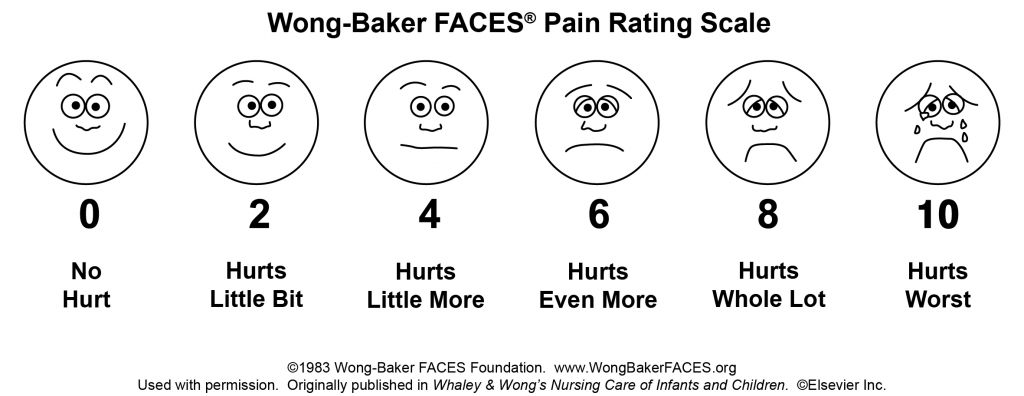

The FACES scale is a visual tool for assessing pain with children and others who cannot quantify the severity of their pain on a scale of 0 to 10. See Figure 11.5[2] for the FACES Pain Rating Scale. To use this scale, use the following evidence-based instructions. Explain to the patient that each face represents a person who has no pain (hurt), some pain, or a lot of pain. “Face 0 doesn’t hurt at all. Face 2 hurts just a little. Face 4 hurts a little more. Face 6 hurts even more. Face 8 hurts a whole lot. Face 10 hurts as much as you can imagine, although you don’t have to be crying to have this worst pain.” Ask the person to choose the face that best represents the pain they are feeling.[3]

FLACC Scale

The FLACC scale (i.e., the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability scale) is a measurement used to assess pain for children between the ages of 2 months and 7 years or individuals who are unable to verbally communicate their pain. The scale has five criteria, which are each assigned a score of 0, 1, or 2. The scale is scored in a range of 0–10 with “0” representing no pain.[4] See Table 11.3b for the FLACC scale.

Table 11.3b The FLACC Scale[5]

| Criteria | Score 0 | Score 1 | Score 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Face | No particular expression or smile | Occasional grimace or frown, withdrawn, or uninterested | Frequent to constant quivering chin; clenched jaw |

| Legs | Normal position or relaxed | Uneasy, restless, or tense | Kicking or legs drawn up |

| Activity | Lying quietly, normal position, and moves easily | Squirming, shifting, back and forth, or tense | Arched, rigid, or jerking |

| Cry | No cry (awake or asleep) | Moans or whimpers or occasional complaint | Crying steadily, screams or sobs, or frequent complaints |

| Consolability | Content and relaxed | Reassured by occasional touching, hugging, or being talked to; distractible | Difficult to console or comfort |

COMFORT Behavioral Scale

The COMFORT Behavioral Scale is a behavioral-observation tool validated for use in children of all ages who are receiving mechanical ventilation. Eight physiological and behavioral indicators are scored on a scale of 1 to 5 to assess pain and sedation.[6]

Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) Scale

The Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) Scale is a simple, valid, and reliable instrument for assessing pain in noncommunicative patients with advanced dementia. See Table 11.3c for the items included on the scale. Each item is scored from 0-2, When totaled, the score can range from 0 (no pain) to 10 (severe pain).

Table 11.3c The PAINAD Scale[7]

| Item | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Breathing independent of vocalization | Normal | Occasional labored breathing. Short period of hyperventilation. | Noisy labored breathing. Long period of hyperventilation. Cheyne-Stokes respirations. |

| Negative vocalization | None | Occasional moan or groan. Low-level speech with a negative or disapproving quality. | Repeated troubled calling out. Loud moaning or groaning. Crying. |

| Facial Expression | Smiling or inexpressive | Sad. Frightened. Frown. | Facial grimacing. |

| Body language | Relaxed | Tense. Distressed pacing. Fidgeting. | Rigid. Fists clenched. Knees pulled up. Pulling or pushing away. Striking out. |

| Consolability | No need to console | Distracted or reassured by voice or touch. | Unable to console, distract, or reassure. |

Comfort-Function Goals

Comfort-function goals encourage the patient to establish their level of comfort needed to achieve functional goals based on their current health status. For example, one patient may be comfortable ambulating after surgery and their pain level is 3 on a 0-to-10 pain intensity rating scale, whereas another patient desires a pain level of 0 on a 0-to-10 scale in order to feel comfortable ambulating. To properly establish a patient's comfort-function goal, nurses must first describe the essential activities of recovery and explain the link between pain control and positive outcomes.[9]

If a patient's pain score exceeds their comfort-function goal, nurses must implement an intervention and follow up within 1 hour to ensure that the intervention was successful. Using the previous example, if a patient had established a comfort-function goal of 3 to ambulate and the current pain rating was 6, the nurse would provide appropriate interventions, such as medication, application of cold packs, or relaxation measures. Documentation of the comfort-function goal, pain level, interventions, and follow-up are key to effective, individualized pain management.[10]