Nursing Process

4.7 Implementation of Interventions

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Implementation is the fifth step of the nursing process (and the fifth Standard of Practice set by the American Nurses Association). This standard is defined as, “The registered nurse implements the identified plan.” The RN may delegate planned interventions after considering the circumstance, person, task, communication, supervision, and evaluation, as well as the state Nurse Practice Act, federal regulation, and agency policy.[1]

Implementation of interventions requires the RN to use critical thinking and clinical judgment. After the initial plan of care is developed, continual reassessment of the patient is necessary to detect any changes in the patient’s condition requiring modification of the plan. The need for continual patient reassessment underscores the dynamic nature of the nursing process and is crucial to providing safe care.

During the implementation phase of the nursing process, the nurse prioritizes planned interventions, assesses patient safety while implementing interventions, delegates interventions as appropriate, and documents interventions performed.

Prioritizing Implementation of Interventions

Prioritizing implementation of interventions follows a similar method as to prioritizing nursing diagnoses. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and the ABCs of airway, breathing, and circulation are used to establish top priority interventions. When possible, least invasive actions are usually preferred due to the risk of injury from invasive options. Read more about methods for prioritization under the “Diagnosis” subsection of this chapter.

The potential impact on future events, especially if a task is not completed at a certain time, is also included when prioritizing nursing interventions. For example, if a patient is scheduled to undergo a surgical procedure later in the day, the nurse prioritizes initiating a NPO (nothing by mouth) prescription prior to completing pre-op patient education about the procedure. The rationale for this decision is that if the patient ate food or drank water, the surgery time would be delayed. Knowing and understanding the patient’s purpose for care, current situation, and expected outcomes are necessary to accurately prioritize interventions.

Patient Safety

It is essential to consider patient safety when implementing interventions. At times, patients may experience a change in condition that makes a planned nursing intervention or provider prescription no longer safe to implement. For example, an established nursing care plan for a patient states, “The nurse will ambulate the patient 100 feet three times daily.” However, during assessment this morning, the patient reports feeling dizzy today, and their blood pressure is 90/60. Using critical thinking and clinical judgment, the nurse decides to not implement the planned intervention of ambulating the patient. This decision and supporting assessment findings should be documented in the patient’s chart and also communicated during the shift handoff report, along with appropriate notification of the provider of the patient’s change in condition.

Implementing interventions goes far beyond implementing provider prescriptions and completing tasks identified on the nursing care plan and must focus on patient safety. As front-line providers, nurses are in the position to stop errors before they reach the patient.[2]

In 2000 the Institute of Medicine (IOM) issued a groundbreaking report titled To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. The report stated that as many as 98,000 people die in U.S. hospitals each year as a result of preventable medical errors. To Err Is Human broke the silence that previously surrounded the consequences of medical errors and set a national agenda for reducing medical errors and improving patient safety through the design of a safer health system.[3] In 2007 the IOM published a follow-up report titled Preventing Medication Errors and reported that more than 1.5 million Americans are injured every year in American hospitals, and the average hospitalized patient experiences at least one medication error each day. This report emphasized actions that health care systems could take to improve medication safety.[4]

In an article released by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, errors involving nurses that endanger patient safety cover broad territory. This territory spans “wrong site, wrong patient, wrong procedure” errors, medication mistakes, failures to follow procedures that prevent central line bloodstream and other infections, errors that allow unsupervised patients to fall, and more. Some errors can be traced to shifts that are too long that leave nurses fatigued, some result from flawed systems that do not allow for adequate safety checks, and others are caused by interruptions to nurses while they are trying to administer medications or provide other care.[5]

The Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) project began in 2005 to assist in preparing future nurses to continuously improve the quality and safety of the health care systems in which they work. The vision of the QSEN project is to “inspire health care professionals to put quality and safety as core values to guide their work.”[6] Nurses and nursing students are expected to participate in quality improvement (QI) initiatives by identifying gaps where change is needed and assisting in implementing initiatives to resolve these gaps. Quality improvement is defined as, “The combined and unceasing efforts of everyone – health care professionals, patients and their families, researchers, payers, planners and educators – to make the changes that will lead to better patient outcomes (health), better system performance (care), and better professional development (learning).”[7]

Delegation of Interventions

While implementing interventions, RNs may elect to delegate nursing tasks. Delegation is defined by the American Nurses Association as, “The assignment of the performance of activities or tasks related to patient care to unlicensed assistive personnel or licensed practical nurses (LPNs) while retaining accountability for the outcome.”[8] RNs are accountable for determining the appropriateness of the delegated task according to condition of the patient and the circumstance; the communication provided to an appropriately trained LPN or UAP; the level of supervision provided; and the evaluation and documentation of the task completed. The RN must also be aware of the state Nurse Practice Act, federal regulations, and agency policy before delegating. The RN cannot delegate responsibilities requiring clinical judgment.[9] See the following box for information regarding legal requirements associated with delegation according to the Wisconsin Nurse Practice Act.

Delegation According to the Wisconsin Nurse Practice Act

During the supervision and direction of delegated acts a Registered Nurse shall do all of the following:

(a) Delegate tasks commensurate with educational preparation and demonstrated abilities of the person supervised.

(b) Provide direction and assistance to those supervised.

(c) Observe and monitor the activities of those supervised.

(d) Evaluate the effectiveness of acts performed under supervision.[10]

The standard of practice for Licensed Practical Nurses in Wisconsin states, “In the performance of acts in basic patient situations, the LPN. shall, under the general supervision of an RN or the direction of a provider:

(a) Accept only patient care assignments which the LPN is competent to perform.

(b) Provide basic nursing care. Basic nursing care is defined as care that can be performed following a defined nursing procedure with minimal modification in which the responses of the patient to the nursing care are predictable.

(c) Record nursing care given and report to the appropriate person changes in the condition of a patient.

(d) Consult with a provider in cases where an LPN knows or should know a delegated act may harm a patient.

(e) Perform the following other acts when applicable:

- Assist with the collection of data.

- Assist with the development and revision of a nursing care plan.

- Reinforce the teaching provided by an RN provider and provide basic health care instruction.

- Participate with other health team members in meeting basic patient needs.”[11]

Read additional details about the scope of practice of registered nurses (RNs) and licensed practical nurses (LPNs) in Wisconsin’s Nurse Practice Act in Chapter N 6 Standards of Practice.

Read more about the American Nurses Association’s Principles of Delegation.

Table 4.7 outlines general guidelines for delegating nursing tasks in the state of Wisconsin according to the role of the health care team member.

Table 4.7 General Guidelines for Delegating Nursing Tasks

| RN | LPN | CNA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | Complete patient assessment | Assist with the collection of data for stable patients | Collect measurements such as weight, input/output, and vital signs in stable patients |

| Diagnosis | Analyze assessment data and create nursing diagnoses | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Outcome Identification | Identify SMART patient outcomes | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Planning | Plan nursing interventions | Assist with the development of a nursing care plan | Not applicable |

| Implementing Interventions | Implement independent, dependent, and collaborative nursing interventions; delegate interventions as appropriate, with supervision | Participate with other health team members in meeting basic patient needs

Reinforce the teaching provided by an RN provider and provide basic health care instruction |

Implement and document delegated interventions associated with basic nursing care such as providing assistance in ambulating or tasks within their scope of practice |

| Evaluation | Evaluate the attainment of outcomes and revise the nursing care plan as needed | Contribute data regarding the achievement of patient outcomes; assist in the revision of a nursing care plan | Not applicable |

Documentation of Interventions

As interventions are performed, they must be documented in the patient’s record in a timely manner. As previously discussed in the “Ethical and Legal Issues” subsection of the “Basic Concepts” section, lack of documentation is considered a failure to communicate and a basis for legal action. A basic rule of thumb is if an intervention is not documented, it is considered not done in a court of law. It is also important to document administration of medication and other interventions in a timely manner to prevent errors that can occur due to delayed documentation time.

Coordination of Care and Health Teaching/Health Promotion

ANA’s Standard of Professional Practice for Implementation also includes the standards 5A Coordination of Care and 5B Health Teaching and Health Promotion.[12] Coordination of Care includes competencies such as organizing the components of the plan, engaging the patient in self-care to achieve goals, and advocating for the delivery of dignified and holistic care by the interprofessional team. Health Teaching and Health Promotion is defined as, “Employing strategies to teach and promote health and wellness.”[13] Patient education is an important component of nursing care and should be included during every patient encounter. For example, patient education may include teaching about side effects while administering medications or teaching patients how to self-manage their conditions at home.

Putting It Together

Refer to Scenario C in the “Assessment” section of this chapter. The nurse implemented the nursing care plan documented in Appendix C. Interventions related to breathing were prioritized. Administration of the diuretic medication was completed first, and lung sounds were monitored frequently for the remainder of the shift. Weighing the patient before breakfast was delegated to the CNA. The patient was educated about her medications and methods to use to reduce peripheral edema at home. All interventions were documented in the electronic medical record (EMR).

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2011, April 28). Nurses are key to improving patient safety. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/articles-and-news/2011/04/nurses-are-key-to-improving-patient-safety.html ↵

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Kohn, L. T., Corrigan, J. M., & Donaldson, M. S. (Eds.). (2000). To err is human: Building a safer health system. National Academies Press. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25077248/ ↵

- Institute of Medicine. (2007). Preventing medication errors. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11623. ↵

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2011, April 28). Nurses are key to improving patient safety. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/articles-and-news/2011/04/nurses-are-key-to-improving-patient-safety.html ↵

- QSEN Institute. (n.d.). Project overview: The evolution of the quality and safety education for nurses (QSEN) initiative. http://qsen.org/about-qsen/project-overview/ ↵

- Batalden, P. B., & Davidoff, F. (2007). What is "quality improvement" and how can it transform healthcare?. BMJ Quality & Safety, 16(1), 2–3. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2006.022046 ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2013). ANA’s principles for delegation by registered nurses to unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP). American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/~4af4f2/globalassets/docs/ana/ethics/principlesofdelegation.pdf ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- Wisconsin Administrative Code. (2018). Chapter N 6 standards of practice for registered nurses and licensed practical nurses. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/code/admin_code/n/6.pdf ↵

- Wisconsin Administrative Code. (2018). Chapter N 6 standards of practice for registered nurses and licensed practical nurses. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/code/admin_code/n/6.pdf ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

Several body systems contribute to a person's oxygenation status, including the respiratory, cardiovascular, and hematological systems. These systems are reviewed in the following sections.

Respiratory System

The main function of our respiratory system is to provide the body with a constant supply of oxygen and to remove carbon dioxide. To achieve these functions, muscles and structures of the thorax create the mechanical movement of air into and out of the lungs called ventilation. Gas exchange occurs at the alveolar level where blood is oxygenated and carbon dioxide is removed, which is called respiration. Several respiratory conditions can affect a patient’s ability to maintain adequate ventilation and respiration, and there are several medications used to enhance a patient's oxygenation status. Use the following hyperlinks to review information regarding the anatomy and physiology of the respiratory system, common respiratory conditions, and classes of respiratory medications.

Read additional information about the "Respiratory System" in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology or use the following hyperlinks to go to specific subsections of the chapter:

-

- Review the anatomy and physiology of the respiratory system.

- Learn about common respiratory disorders.

- Read about common respiratory medications

.

Cardiovascular System

In order for oxygenated blood to move from the alveoli in the lungs to the various organs and tissues of the body, the heart must adequately pump blood through the systemic arteries. The amount of blood that the heart pumps in one minute is referred to as cardiac output. The passage of blood through arteries to an organ or tissue is referred to as perfusion. Several cardiac conditions can adversely affect cardiac output and perfusion in the body. There are several medications used to enhance a patient's cardiac output and maintain adequate perfusion to organs and tissues throughout the body. Use the following hyperlinks to review information regarding the anatomy and physiology of the cardiovascular system, common cardiac disorders, and various cardiovascular system medications.

Read additional information about the cardiovascular system in the "Cardiovascular & Renal" chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology or use the following hyperlinks to go to specific subsections of this chapter:

- Review the anatomy and physiology of the cardiovascular system.

- Learn about common cardiac disorders.

- Read about common cardiovascular system medications.

Hematological System

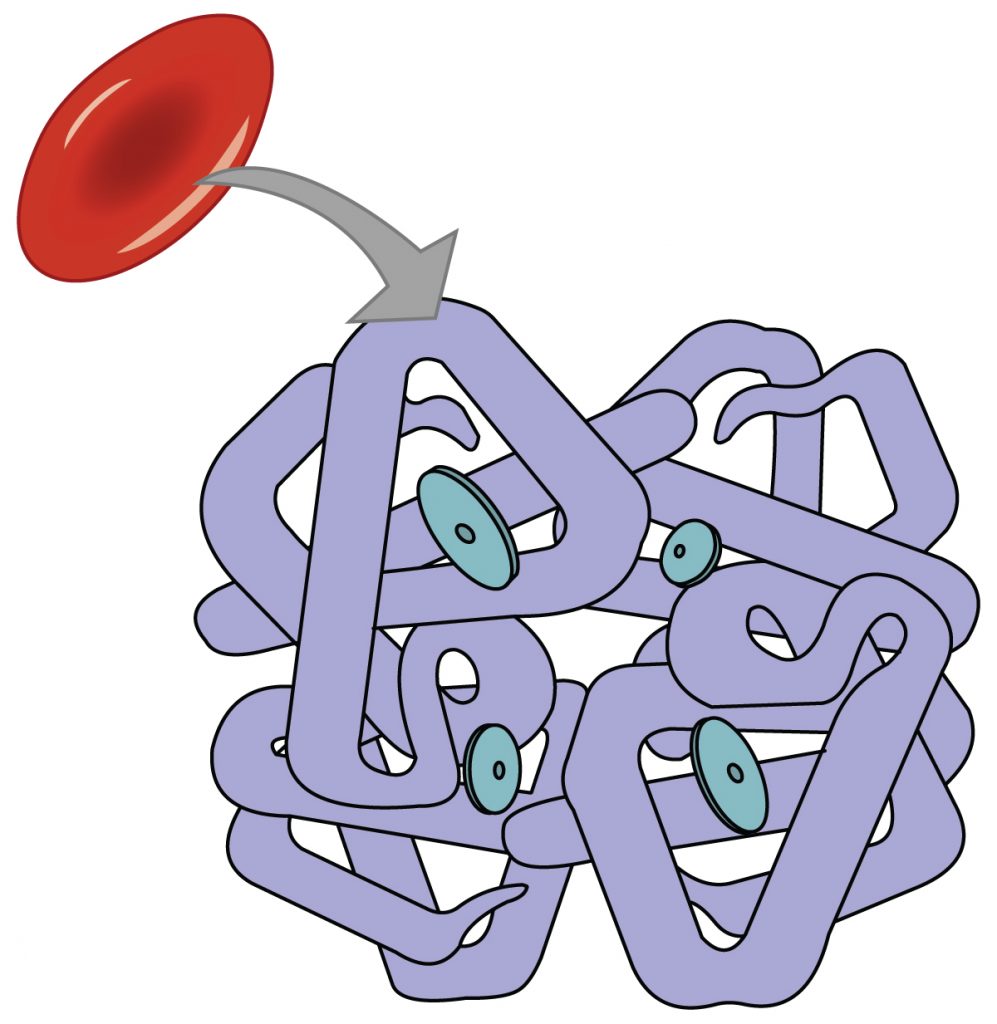

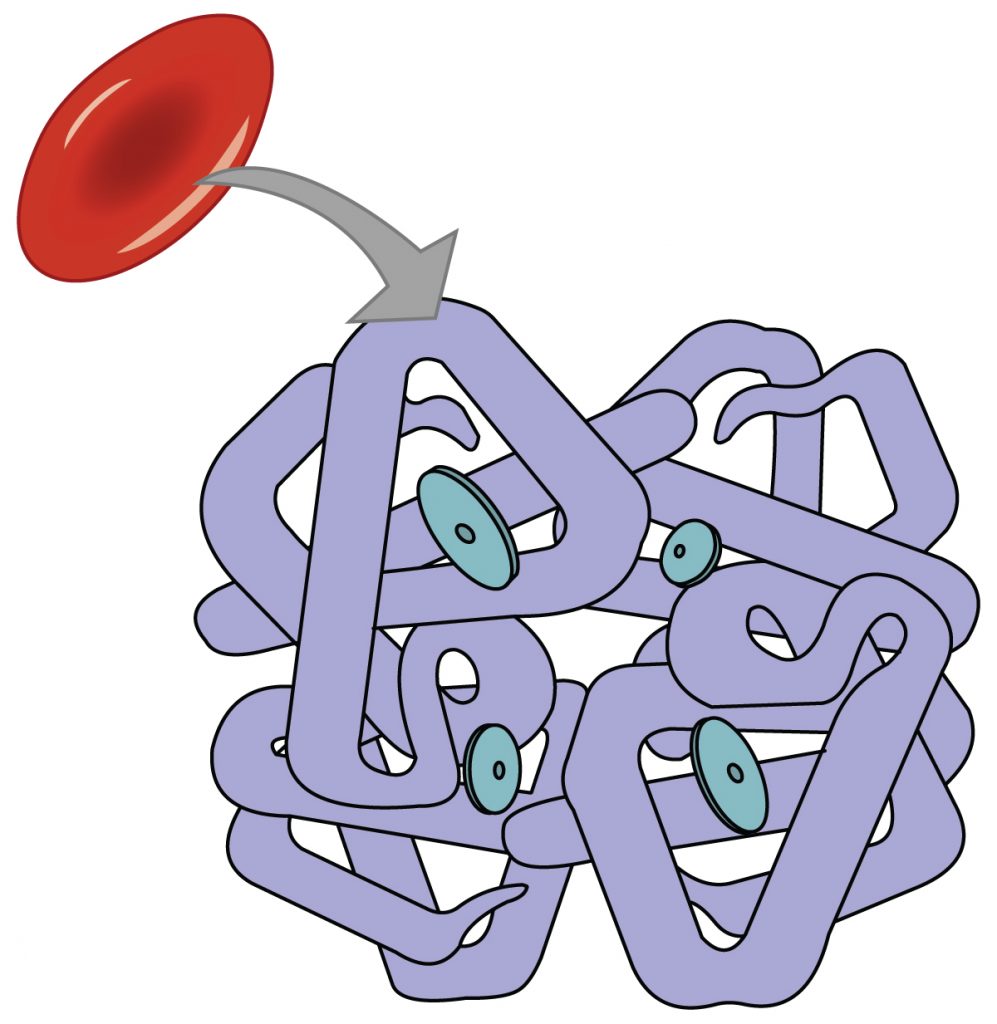

Although the bloodstream carries small amounts of dissolved oxygen, the majority of oxygen molecules are transported throughout the body by attaching to hemoglobin within red blood cells. Each hemoglobin protein is capable of carrying four oxygen molecules. When all four hemoglobin structures contain an oxygen molecule, it is referred to as “saturated.”[1] See Figure 8.1[2] for an image of hemoglobin protein within a red blood cell with four sites for carrying oxygen molecules.

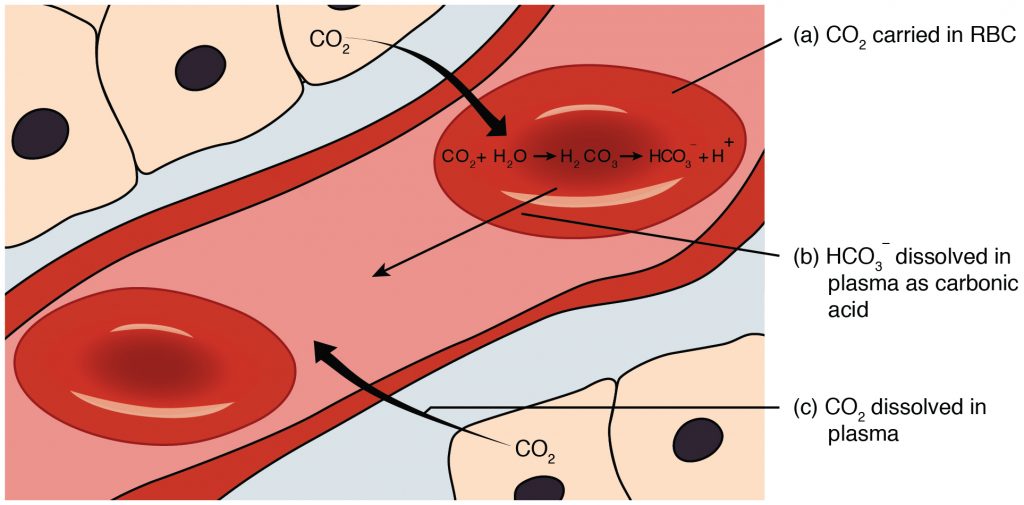

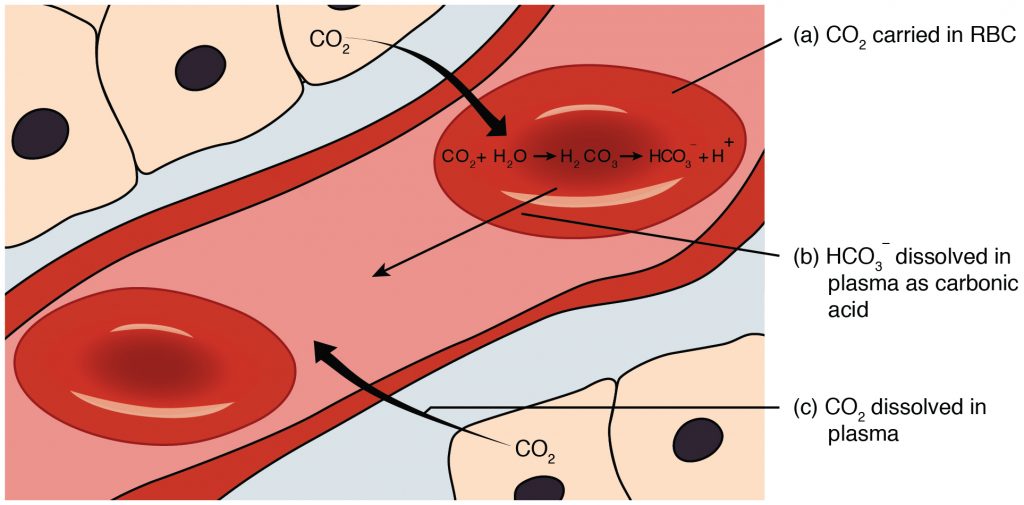

When oxygenated blood reaches tissues within the body, oxygen is released from the hemoglobin, and carbon dioxide is picked up and transported to the lungs for release on exhalation. Carbon dioxide is transported throughout the body by three major mechanisms: dissolved carbon dioxide, attachment to water as HCO3-, and attachment to the hemoglobin in red blood cells.[3] See Figure 8.2[4] for an illustration of carbon dioxide transport.[5]

Measuring Oxygen, Carbon Dioxide, and Acid Base Levels

Because the majority of oxygen transported in the blood is attached to hemoglobin, a patient’s oxygenation status is easily assessed using pulse oximetry, referred to as SpO2. See Figure 8.3[6] for an image of a pulse oximeter. This reading refers to the amount of hemoglobin that is saturated. The target range of SpO2 for an adult is 94-98%.[7] For patients with chronic oxygenation conditions such as COPD, the target range for SpO2 is often lower at 88% to 92%. Although SpO2 is an efficient, noninvasive method for assessing a patient’s oxygenation status, it is not always accurate. For example, if a patient is severely anemic, the patient has a decreased amount of hemoglobin in the blood available to carry the oxygen, which subsequently affects the SpO2 reading. Decreased perfusion of the extremities can also cause inaccurate SpO2 levels because less blood delivered to the tissues causes a false low SpO2. Additionally, other substances can attach to hemoglobin such as carbon monoxide, causing a falsely elevated SpO2.

A more specific measurement of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood is obtained using an arterial blood gas (ABG). ABG results are often used for patients who have deteriorating or unstable respiratory status requiring emergency treatment. An ABG is a blood sample that is typically drawn from the radial artery by a respiratory therapist. ABG results indicate oxygen, carbon dioxide, pH, and bicarbonate levels. The partial pressure of oxygen in the arterial blood is referred to as PaO2. PaO2 measures the pressure of oxygen dissolved in the arterial blood and how well oxygen is able to move from the lungs into the blood. The normal PaO2 level of a healthy adult is 80 to 100 mmHg. The PaO2 reading is more accurate than a SpO2 reading because it is not affected by hemoglobin levels. The partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the arterial blood is the PaCO2 level. The PaCO2 level measures the pressure of carbon dioxide dissolved in the blood and how well carbon dioxide is able to move out of the body. It is typically used to determine if sufficient ventilation is occurring at the alveolar level. The normal PaCO2 level of a healthy adult is 35-45 mmHg. The normal range of pH level for arterial blood is 7.35-7.45, and the normal range for the bicarbonate (HCO3-) level is 22-26. The SaO2 level is also calculated in ABG results, which is the calculated arterial oxygen saturation level.[8]

Hypoxia and Hypercapnia

Hypoxia is defined as a reduced level of tissue oxygenation. Hypoxia has many causes, ranging from respiratory and cardiac conditions to anemia. Hypoxemia is a specific type of hypoxia that is defined as decreased partial pressure of oxygen in the blood (PaO2) indicated in an arterial blood gas (ABG) result.

Early signs of hypoxia are anxiety, confusion, and restlessness. As hypoxia worsens, the patient’s level of consciousness and vital signs will worsen with an increased respiratory rate and heart rate and decreased pulse oximetry readings. Late signs of hypoxia include bluish discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes called cyanosis. See Figure 8.4[9] for an image of cyanosis.

Hypercapnia, also referred to as hypercarbia, is an elevated level of carbon dioxide in the blood. This level is measured by the PaCO2 level in an ABG test and is indicated when the PaCO2 level is greater than 45. Hypercapnia is caused by hypoventilation or when the alveoli are ventilated but not perfused. In a state of hypercapnia, the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the blood causes the pH of the blood to drop, leading to a state of respiratory acidosis. You can read more about respiratory acidosis in the "Acid-Base Balance" section of the “Fluids and Electrolytes” chapter. Patients with hypercapnia have symptoms such as tachycardia, dyspnea, flushed skin, confusion, headaches, and dizziness. If the hypercapnia develops gradually over time, symptoms may be mild or may not be present at all. Hypercapnia is managed by addressing its underlying cause. A noninvasive positive pressure device such as a BiPAP may be used to help eliminate the excess carbon dioxide, but if this is not sufficient, intubation may be required.[10] You can read more about BiPAP devices and intubation in the “Oxygen Therapy” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills.

It is important for a nurse to recognize early signs of respiratory distress and report changes in patient condition to prevent respiratory failure. See Table 8.2a for symptoms and signs of respiratory distress.[11]

Table 8.2a Symptoms and Signs of Respiratory Distress

| Signs and Symptoms | Description |

|---|---|

| Shortness of breath (Dyspnea) | Dyspnea is a subjective symptom of not getting enough air. Depending on severity, dyspnea causes increased levels of anxiety. |

| Restlessness | An early sign of hypoxia. |

| Tachycardia | An elevated heart rate (above 100 beats per minute in adults) can be an early sign of hypoxia. |

| Tachypnea | An increased respiration rate (above 20 breaths per minute in adults) is an indication of respiratory distress. |

| Oxygen saturation level (SpO2) | Oxygen saturation levels should be above 94% for an adult without an underlying respiratory condition. |

| Use of accessory muscles | Use of neck or intercostal muscles when breathing is an indication of respiratory distress. |

| Noisy breathing | Audible noises with breathing are an indication of respiratory conditions. Further assess lung sounds with a stethoscope for adventitious sounds such as wheezing, rales, or crackles. Secretions can plug the airway, thereby decreasing the amount of oxygen available for gas exchange in the lungs. |

| Flaring of nostrils | Nasal flaring is a sign of respiratory distress, especially in infants. |

| Skin color (Cyanosis) |

Bluish changes in skin color and mucus membranes is a late sign of hypoxia. |

| Position of patient | Patients in respiratory distress often automatically sit up and lean over by resting arms on their legs, referred to as the tripod position. The tripod position enhances lung expansion. Conversely, patients who are hypoxic often feel worse dyspnea when lying flat in bed and avoid the supine position. |

| Ability of patient to speak in full sentences | Patients in respiratory distress may be unable to speak in full sentences or may need to catch their breath between sentences. |

| Confusion or change in level of consciousness (LOC) | Confusion can be an early sign of hypoxia and changing level of consciousness is a worsening sign of hypoxia. |

Treating Hypoxia and Hypercapnia

Hypoxia and/or hypercapnia are medical emergencies and should be treated promptly by calling for assistance as indicated by agency policy.

Failure to initiate oxygen therapy when needed can result in serious harm or death of the patient. Although oxygen is considered a medication that requires a prescription, oxygen therapy may be initiated without a physician’s order in emergency situations as part of the nurse’s response to the “ABCs,” a common abbreviation for airway, breathing, and circulation. Most agencies have a protocol in place that allows nurses to apply oxygen in emergency situations and obtain the necessary order at a later time.[12]

In addition to administering oxygen therapy, there are several other interventions a nurse can implement to assist an hypoxic patient. Additional interventions used to treat hypoxia in conjunction with oxygen therapy are outlined in Table 8.2b.

Table 8.2b Interventions to Manage Hypoxia

| Interventions | Additional Information |

|---|---|

| Raise the head of the bed. | Raising the head of the bed to high Fowler’s position promotes effective chest expansion and diaphragmatic descent, maximizes inhalation, and decreases the work of breathing. |

| Use tripod positioning. | Situate the patient in a tripod position. Patients who are short of breath may gain relief by sitting upright and leaning over a bedside table while in bed, which is called a three-point or tripod position. |

| Encourage enhanced breathing and coughing techniques. | Enhanced breathing and coughing techniques such as using pursed-lip breathing, coughing and deep breathing, huffing technique, incentive spirometry, and flutter valves may assist patients to clear their airway while maintaining their oxygen levels. See the “Enhanced Breathing and Coughing Techniques” section below for additional information regarding these techniques. |

| Manage oxygen therapy and equipment. | If the patient is already on supplemental oxygen, ensure the equipment is turned on, set at the required flow rate, and is properly connected to an oxygen supply source. If a portable tank is being used, check the oxygen level in the tank. Ensure the connecting oxygen tubing is not kinked, which could obstruct the flow of oxygen. Feel for the flow of oxygen from the exit ports on the oxygen equipment. In hospitals where medical air and oxygen are used, ensure the patient is connected to the oxygen flow port.

Various types of oxygenation equipment are prescribed for patients requiring oxygen therapy. Oxygenation equipment is typically managed in collaboration with a respiratory therapist in hospital settings. Equipment includes devices such as nasal cannula, masks, Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP), Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure (BiPAP), and mechanical ventilators. For more information, see the “Oxygenation Equipment” section of the "Oxygen Therapy" chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills. |

| Assess the need for respiratory medications. | Pharmacological management is essential for patients with respiratory disease such as asthma, COPD, or severe allergic response. Bronchodilators effectively relax smooth muscles and open airways. Glucocorticoids relieve inflammation and also assist in opening air passages. Mucolytics decrease the thickness of pulmonary secretions so that they can be expectorated more easily. |

| Provide suctioning, if needed. | Some patients may have a weakened cough that inhibits their ability to clear secretions from the mouth and throat. Patients with muscle disorders or those who have experienced a stroke (i.e., cerebral vascular accident) are at risk for aspiration, which could lead to pneumonia and hypoxia. Provide oral suction if the patient is unable to clear secretions from the mouth and pharynx. See the “Tracheostomy Care and Suctioning” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills for additional details on suctioning. |

| Provide pain relief, If needed. | Provide adequate pain relief if the patient is reporting pain. Pain increases anxiety and metabolic demands, which, in turn, increase the need for more oxygen supply. |

| Consider side effects of pain medication. | A common side effect of pain medication is respiratory depression. For more information about managing respiratory depression, see the “Pain Management” section of the "Comfort" chapter. |

| Consider other devices to enhance clearance of secretions. | Chest physiotherapy and specialized devices assist with secretion clearance, such as handheld flutter valves or vests that inflate and vibrate the chest wall. Consult with a respiratory therapist as needed based on the patient’s situation. |

| Plan frequent rest periods between activities. | Plan interventions for patients with dyspnea so they can rest frequently and decrease oxygen demand. |

| Consider other potential causes of dyspnea. | If a patient’s level of dyspnea is worsening, assess for other underlying causes in addition to the primary diagnosis. For example, are there other respiratory, cardiovascular, or hematological conditions occurring? Start by reviewing the patient’s most recent hemoglobin and hematocrit lab results, as well as any other diagnostic tests such as chest X-rays and ABG results. Completing a thorough assessment may reveal abnormalities in these systems to report to the health care provider. |

| Consider obstructive sleep apnea. | Patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) are often not previously diagnosed prior to hospitalization. The nurse may notice the patient snores, has pauses in breathing while snoring, has decreased oxygen saturation levels while sleeping, or awakens feeling not rested. These signs may indicate the patient is unable to maintain an open airway while sleeping, resulting in periods of apnea and hypoxia. If these apneic periods are noticed but have not been previously documented, the nurse should report these findings to the health care provider for further testing and follow-up. A prescription for a CPAP or BiPAP device while sleeping may be needed to prevent adverse outcomes. |

| Monitor patient's anxiety. | Assess patient’s anxiety. Anxiety often accompanies the feeling of dyspnea and can worsen it. Anxiety in patients with COPD is chronically undertreated. It is important for the nurse to address the feelings of anxiety in addition to the feelings of dyspnea. Anxiety can be relieved by teaching enhanced breathing and coughing techniques, encouraging relaxation techniques, or administering antianxiety medications. |

Enhanced Breathing and Coughing Techniques

In addition to oxygen therapy and the interventions listed in Table 8.2b, there are several techniques a nurse can teach a patient to use to enhance their breathing and coughing. These techniques include pursed-lip breathing, incentive spirometry, coughing and deep breathing, and the huffing technique. Additionally, vibratory positive expiratory pressure (PEP) therapy can be incorporated in collaboration with a respiratory therapist.

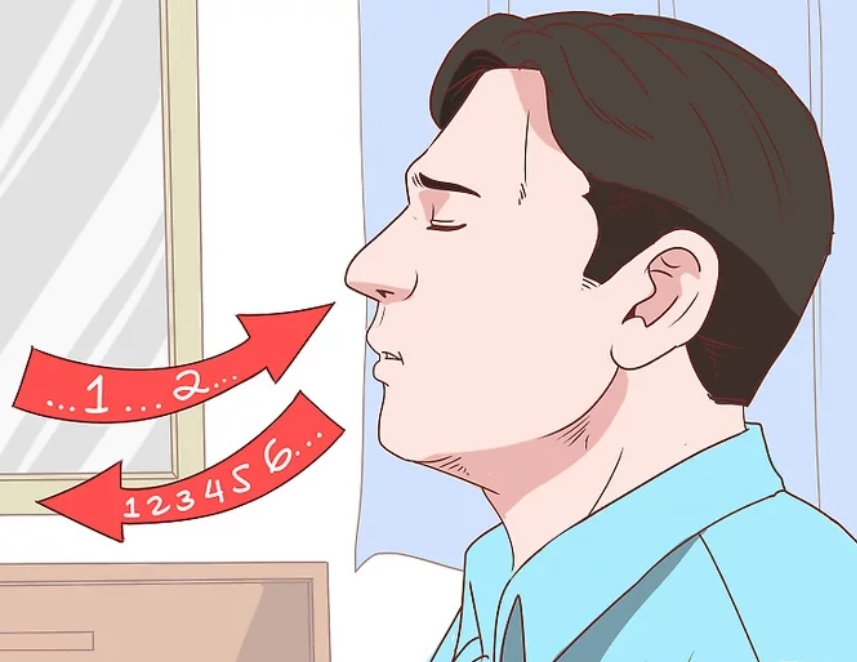

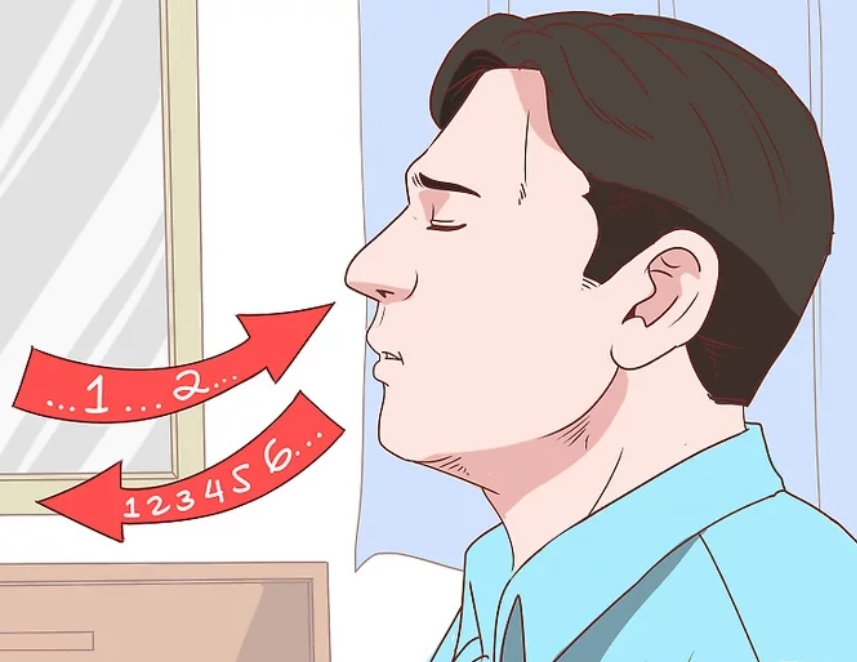

Pursed-lip Breathing

Pursed-lip breathing is a technique that decreases dyspnea by teaching people to control their oxygenation and ventilation. See Figure 8.5[13] for an illustration of pursed-lip breathing. The technique teaches a person to inhale through the nose and exhale through the mouth at a slow, controlled flow. This type of exhalation gives the person a puckered or pursed-lip appearance. By prolonging the expiratory phase of respiration, a small amount of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is created in the airways that helps to keep them open so that more air can be exhaled. This subsequently reduces air trapping that commonly occurs in conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Pursed-lip breathing relieves the feeling of shortness of breath, decreases the work of breathing, and improves gas exchange. People also regain a sense of control over their breathing while simultaneously increasing their relaxation.[14]

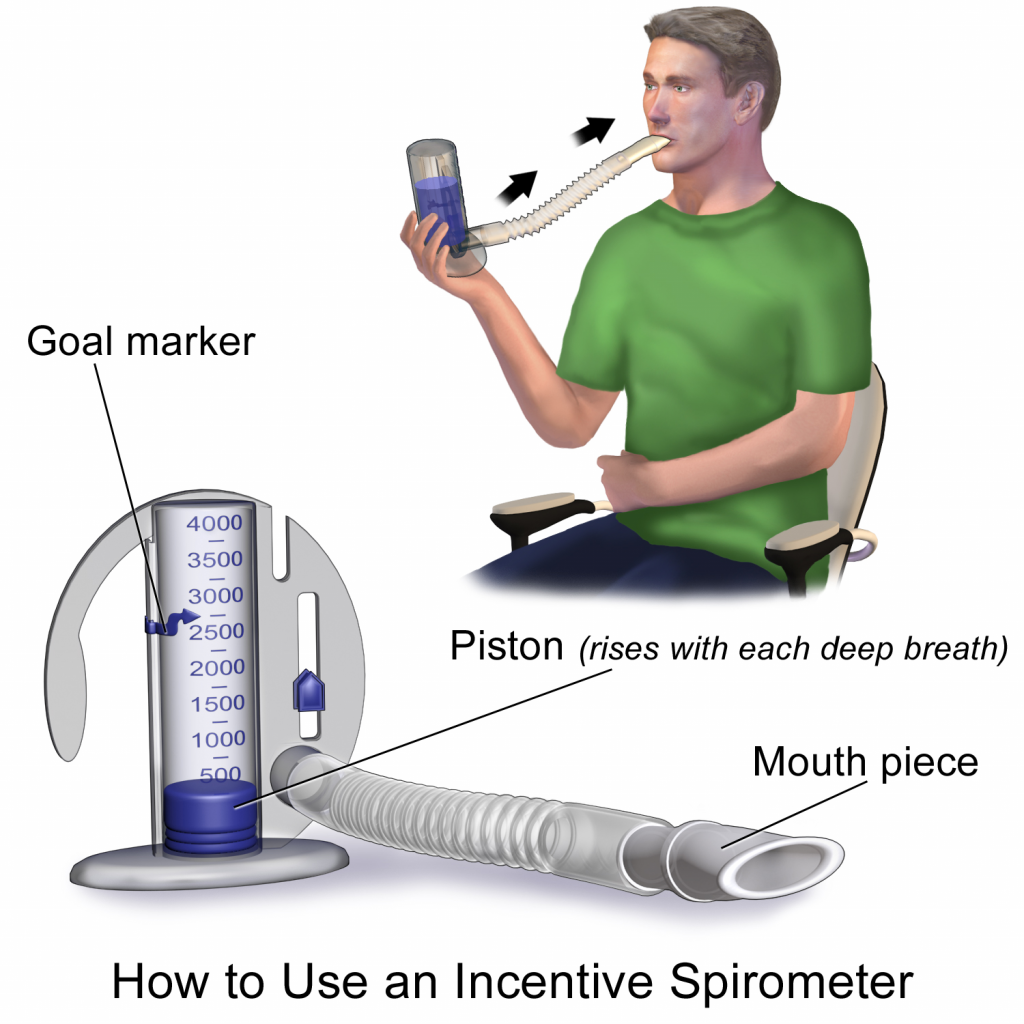

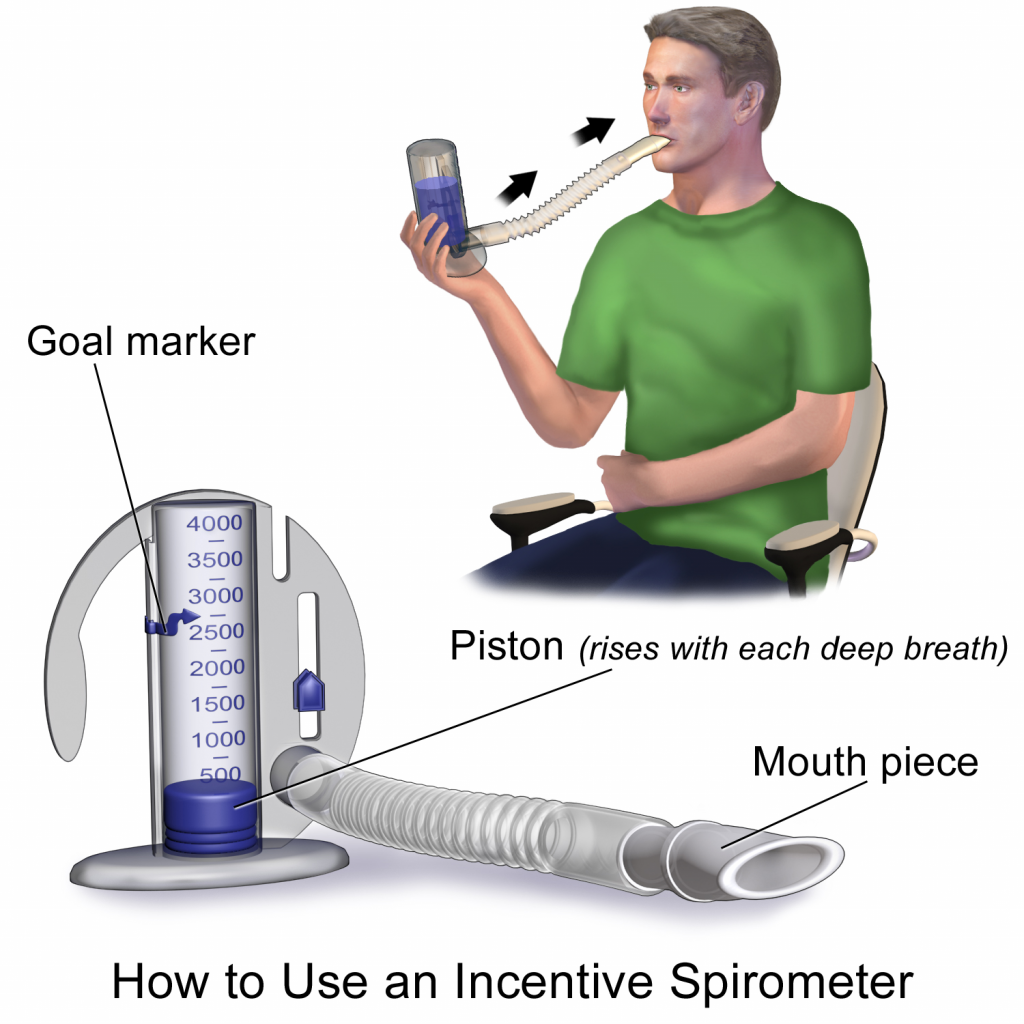

Incentive Spirometry

An incentive spirometer is a medical device commonly prescribed after surgery to expand the lungs, reduce the buildup of fluid in the lungs, and prevent pneumonia. See Figure 8.6[15] for an image of a patient using an incentive spirometer. While sitting upright, if possible, the patient should place the mouthpiece in their mouth and create a tight seal with their lips around it. They should breathe in slowly and as deeply as possible through the tubing with the goal of raising the piston to their prescribed level. The resistance indicator on the right side should be monitored to ensure they are not breathing in too quickly. The patient should attempt to hold their breath for as long as possible (at least 5 seconds) and then exhale and rest for a few seconds. Coughing is expected. Encourage the patient to expel the mucus and not swallow it. This technique should be repeated by the patient 10 times every hour while awake.[16] The nurse may delegate this intervention to unlicensed assistive personnel, but the frequency in which it is completed and the volume achieved should be documented and monitored by the nurse.

Coughing and Deep Breathing

Coughing and deep breathing is a breathing technique similar to incentive spirometry but no device is required. The patient is encouraged to take deep, slow breaths and then exhale slowly. After each set of breaths, the patient should cough. This technique is repeated 3 to 5 times every hour.

Huffing Technique

The huffing technique is helpful to teach patients who have difficulty coughing. Teach the patient to inhale with a medium-sized breath and then make a sound like “ha” to push the air out quickly with the mouth slightly open.

Vibratory PEP Therapy

Vibratory Positive Expiratory Pressure (PEP) Therapy uses handheld devices such as flutter valves or Acapella devices for patients who need assistance in clearing mucus from their airways. These devices require a prescription and are used in collaboration with a respiratory therapist or advanced health care provider. To use vibratory PEP therapy, the patient should sit up, take a deep breath, and blow into the device. A flutter valve within the device creates vibrations that help break up the mucus so the patient can cough and spit it out. Additionally, a small amount of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is created in the airways that helps to keep them open so that more air can be exhaled. See the supplementary video below regarding how to use the flutter valve device.

View this video on Using a Flutter Valve Device (Acapella).[17]

Several body systems contribute to a person's oxygenation status, including the respiratory, cardiovascular, and hematological systems. These systems are reviewed in the following sections.

Respiratory System

The main function of our respiratory system is to provide the body with a constant supply of oxygen and to remove carbon dioxide. To achieve these functions, muscles and structures of the thorax create the mechanical movement of air into and out of the lungs called ventilation. Gas exchange occurs at the alveolar level where blood is oxygenated and carbon dioxide is removed, which is called respiration. Several respiratory conditions can affect a patient’s ability to maintain adequate ventilation and respiration, and there are several medications used to enhance a patient's oxygenation status. Use the following hyperlinks to review information regarding the anatomy and physiology of the respiratory system, common respiratory conditions, and classes of respiratory medications.

Read additional information about the "Respiratory System" in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology or use the following hyperlinks to go to specific subsections of the chapter:

-

- Review the anatomy and physiology of the respiratory system.

- Learn about common respiratory disorders.

- Read about common respiratory medications

.

Cardiovascular System

In order for oxygenated blood to move from the alveoli in the lungs to the various organs and tissues of the body, the heart must adequately pump blood through the systemic arteries. The amount of blood that the heart pumps in one minute is referred to as cardiac output. The passage of blood through arteries to an organ or tissue is referred to as perfusion. Several cardiac conditions can adversely affect cardiac output and perfusion in the body. There are several medications used to enhance a patient's cardiac output and maintain adequate perfusion to organs and tissues throughout the body. Use the following hyperlinks to review information regarding the anatomy and physiology of the cardiovascular system, common cardiac disorders, and various cardiovascular system medications.

Read additional information about the cardiovascular system in the "Cardiovascular & Renal" chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology or use the following hyperlinks to go to specific subsections of this chapter:

- Review the anatomy and physiology of the cardiovascular system.

- Learn about common cardiac disorders.

- Read about common cardiovascular system medications.

Hematological System

Although the bloodstream carries small amounts of dissolved oxygen, the majority of oxygen molecules are transported throughout the body by attaching to hemoglobin within red blood cells. Each hemoglobin protein is capable of carrying four oxygen molecules. When all four hemoglobin structures contain an oxygen molecule, it is referred to as “saturated.”[18] See Figure 8.1[19] for an image of hemoglobin protein within a red blood cell with four sites for carrying oxygen molecules.

When oxygenated blood reaches tissues within the body, oxygen is released from the hemoglobin, and carbon dioxide is picked up and transported to the lungs for release on exhalation. Carbon dioxide is transported throughout the body by three major mechanisms: dissolved carbon dioxide, attachment to water as HCO3-, and attachment to the hemoglobin in red blood cells.[20] See Figure 8.2[21] for an illustration of carbon dioxide transport.[22]

Measuring Oxygen, Carbon Dioxide, and Acid Base Levels

Because the majority of oxygen transported in the blood is attached to hemoglobin, a patient’s oxygenation status is easily assessed using pulse oximetry, referred to as SpO2. See Figure 8.3[23] for an image of a pulse oximeter. This reading refers to the amount of hemoglobin that is saturated. The target range of SpO2 for an adult is 94-98%.[24] For patients with chronic oxygenation conditions such as COPD, the target range for SpO2 is often lower at 88% to 92%. Although SpO2 is an efficient, noninvasive method for assessing a patient’s oxygenation status, it is not always accurate. For example, if a patient is severely anemic, the patient has a decreased amount of hemoglobin in the blood available to carry the oxygen, which subsequently affects the SpO2 reading. Decreased perfusion of the extremities can also cause inaccurate SpO2 levels because less blood delivered to the tissues causes a false low SpO2. Additionally, other substances can attach to hemoglobin such as carbon monoxide, causing a falsely elevated SpO2.

A more specific measurement of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood is obtained using an arterial blood gas (ABG). ABG results are often used for patients who have deteriorating or unstable respiratory status requiring emergency treatment. An ABG is a blood sample that is typically drawn from the radial artery by a respiratory therapist. ABG results indicate oxygen, carbon dioxide, pH, and bicarbonate levels. The partial pressure of oxygen in the arterial blood is referred to as PaO2. PaO2 measures the pressure of oxygen dissolved in the arterial blood and how well oxygen is able to move from the lungs into the blood. The normal PaO2 level of a healthy adult is 80 to 100 mmHg. The PaO2 reading is more accurate than a SpO2 reading because it is not affected by hemoglobin levels. The partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the arterial blood is the PaCO2 level. The PaCO2 level measures the pressure of carbon dioxide dissolved in the blood and how well carbon dioxide is able to move out of the body. It is typically used to determine if sufficient ventilation is occurring at the alveolar level. The normal PaCO2 level of a healthy adult is 35-45 mmHg. The normal range of pH level for arterial blood is 7.35-7.45, and the normal range for the bicarbonate (HCO3-) level is 22-26. The SaO2 level is also calculated in ABG results, which is the calculated arterial oxygen saturation level.[25]

Hypoxia and Hypercapnia

Hypoxia is defined as a reduced level of tissue oxygenation. Hypoxia has many causes, ranging from respiratory and cardiac conditions to anemia. Hypoxemia is a specific type of hypoxia that is defined as decreased partial pressure of oxygen in the blood (PaO2) indicated in an arterial blood gas (ABG) result.

Early signs of hypoxia are anxiety, confusion, and restlessness. As hypoxia worsens, the patient’s level of consciousness and vital signs will worsen with an increased respiratory rate and heart rate and decreased pulse oximetry readings. Late signs of hypoxia include bluish discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes called cyanosis. See Figure 8.4[26] for an image of cyanosis.

Hypercapnia, also referred to as hypercarbia, is an elevated level of carbon dioxide in the blood. This level is measured by the PaCO2 level in an ABG test and is indicated when the PaCO2 level is greater than 45. Hypercapnia is caused by hypoventilation or when the alveoli are ventilated but not perfused. In a state of hypercapnia, the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the blood causes the pH of the blood to drop, leading to a state of respiratory acidosis. You can read more about respiratory acidosis in the "Acid-Base Balance" section of the “Fluids and Electrolytes” chapter. Patients with hypercapnia have symptoms such as tachycardia, dyspnea, flushed skin, confusion, headaches, and dizziness. If the hypercapnia develops gradually over time, symptoms may be mild or may not be present at all. Hypercapnia is managed by addressing its underlying cause. A noninvasive positive pressure device such as a BiPAP may be used to help eliminate the excess carbon dioxide, but if this is not sufficient, intubation may be required.[27] You can read more about BiPAP devices and intubation in the “Oxygen Therapy” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills.

It is important for a nurse to recognize early signs of respiratory distress and report changes in patient condition to prevent respiratory failure. See Table 8.2a for symptoms and signs of respiratory distress.[28]

Table 8.2a Symptoms and Signs of Respiratory Distress

| Signs and Symptoms | Description |

|---|---|

| Shortness of breath (Dyspnea) | Dyspnea is a subjective symptom of not getting enough air. Depending on severity, dyspnea causes increased levels of anxiety. |

| Restlessness | An early sign of hypoxia. |

| Tachycardia | An elevated heart rate (above 100 beats per minute in adults) can be an early sign of hypoxia. |

| Tachypnea | An increased respiration rate (above 20 breaths per minute in adults) is an indication of respiratory distress. |

| Oxygen saturation level (SpO2) | Oxygen saturation levels should be above 94% for an adult without an underlying respiratory condition. |

| Use of accessory muscles | Use of neck or intercostal muscles when breathing is an indication of respiratory distress. |

| Noisy breathing | Audible noises with breathing are an indication of respiratory conditions. Further assess lung sounds with a stethoscope for adventitious sounds such as wheezing, rales, or crackles. Secretions can plug the airway, thereby decreasing the amount of oxygen available for gas exchange in the lungs. |

| Flaring of nostrils | Nasal flaring is a sign of respiratory distress, especially in infants. |

| Skin color (Cyanosis) |

Bluish changes in skin color and mucus membranes is a late sign of hypoxia. |

| Position of patient | Patients in respiratory distress often automatically sit up and lean over by resting arms on their legs, referred to as the tripod position. The tripod position enhances lung expansion. Conversely, patients who are hypoxic often feel worse dyspnea when lying flat in bed and avoid the supine position. |

| Ability of patient to speak in full sentences | Patients in respiratory distress may be unable to speak in full sentences or may need to catch their breath between sentences. |

| Confusion or change in level of consciousness (LOC) | Confusion can be an early sign of hypoxia and changing level of consciousness is a worsening sign of hypoxia. |

Treating Hypoxia and Hypercapnia

Hypoxia and/or hypercapnia are medical emergencies and should be treated promptly by calling for assistance as indicated by agency policy.

Failure to initiate oxygen therapy when needed can result in serious harm or death of the patient. Although oxygen is considered a medication that requires a prescription, oxygen therapy may be initiated without a physician’s order in emergency situations as part of the nurse’s response to the “ABCs,” a common abbreviation for airway, breathing, and circulation. Most agencies have a protocol in place that allows nurses to apply oxygen in emergency situations and obtain the necessary order at a later time.[29]

In addition to administering oxygen therapy, there are several other interventions a nurse can implement to assist an hypoxic patient. Additional interventions used to treat hypoxia in conjunction with oxygen therapy are outlined in Table 8.2b.

Table 8.2b Interventions to Manage Hypoxia

| Interventions | Additional Information |

|---|---|

| Raise the head of the bed. | Raising the head of the bed to high Fowler’s position promotes effective chest expansion and diaphragmatic descent, maximizes inhalation, and decreases the work of breathing. |

| Use tripod positioning. | Situate the patient in a tripod position. Patients who are short of breath may gain relief by sitting upright and leaning over a bedside table while in bed, which is called a three-point or tripod position. |

| Encourage enhanced breathing and coughing techniques. | Enhanced breathing and coughing techniques such as using pursed-lip breathing, coughing and deep breathing, huffing technique, incentive spirometry, and flutter valves may assist patients to clear their airway while maintaining their oxygen levels. See the “Enhanced Breathing and Coughing Techniques” section below for additional information regarding these techniques. |

| Manage oxygen therapy and equipment. | If the patient is already on supplemental oxygen, ensure the equipment is turned on, set at the required flow rate, and is properly connected to an oxygen supply source. If a portable tank is being used, check the oxygen level in the tank. Ensure the connecting oxygen tubing is not kinked, which could obstruct the flow of oxygen. Feel for the flow of oxygen from the exit ports on the oxygen equipment. In hospitals where medical air and oxygen are used, ensure the patient is connected to the oxygen flow port.

Various types of oxygenation equipment are prescribed for patients requiring oxygen therapy. Oxygenation equipment is typically managed in collaboration with a respiratory therapist in hospital settings. Equipment includes devices such as nasal cannula, masks, Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP), Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure (BiPAP), and mechanical ventilators. For more information, see the “Oxygenation Equipment” section of the "Oxygen Therapy" chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills. |

| Assess the need for respiratory medications. | Pharmacological management is essential for patients with respiratory disease such as asthma, COPD, or severe allergic response. Bronchodilators effectively relax smooth muscles and open airways. Glucocorticoids relieve inflammation and also assist in opening air passages. Mucolytics decrease the thickness of pulmonary secretions so that they can be expectorated more easily. |

| Provide suctioning, if needed. | Some patients may have a weakened cough that inhibits their ability to clear secretions from the mouth and throat. Patients with muscle disorders or those who have experienced a stroke (i.e., cerebral vascular accident) are at risk for aspiration, which could lead to pneumonia and hypoxia. Provide oral suction if the patient is unable to clear secretions from the mouth and pharynx. See the “Tracheostomy Care and Suctioning” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills for additional details on suctioning. |

| Provide pain relief, If needed. | Provide adequate pain relief if the patient is reporting pain. Pain increases anxiety and metabolic demands, which, in turn, increase the need for more oxygen supply. |

| Consider side effects of pain medication. | A common side effect of pain medication is respiratory depression. For more information about managing respiratory depression, see the “Pain Management” section of the "Comfort" chapter. |

| Consider other devices to enhance clearance of secretions. | Chest physiotherapy and specialized devices assist with secretion clearance, such as handheld flutter valves or vests that inflate and vibrate the chest wall. Consult with a respiratory therapist as needed based on the patient’s situation. |

| Plan frequent rest periods between activities. | Plan interventions for patients with dyspnea so they can rest frequently and decrease oxygen demand. |

| Consider other potential causes of dyspnea. | If a patient’s level of dyspnea is worsening, assess for other underlying causes in addition to the primary diagnosis. For example, are there other respiratory, cardiovascular, or hematological conditions occurring? Start by reviewing the patient’s most recent hemoglobin and hematocrit lab results, as well as any other diagnostic tests such as chest X-rays and ABG results. Completing a thorough assessment may reveal abnormalities in these systems to report to the health care provider. |

| Consider obstructive sleep apnea. | Patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) are often not previously diagnosed prior to hospitalization. The nurse may notice the patient snores, has pauses in breathing while snoring, has decreased oxygen saturation levels while sleeping, or awakens feeling not rested. These signs may indicate the patient is unable to maintain an open airway while sleeping, resulting in periods of apnea and hypoxia. If these apneic periods are noticed but have not been previously documented, the nurse should report these findings to the health care provider for further testing and follow-up. A prescription for a CPAP or BiPAP device while sleeping may be needed to prevent adverse outcomes. |

| Monitor patient's anxiety. | Assess patient’s anxiety. Anxiety often accompanies the feeling of dyspnea and can worsen it. Anxiety in patients with COPD is chronically undertreated. It is important for the nurse to address the feelings of anxiety in addition to the feelings of dyspnea. Anxiety can be relieved by teaching enhanced breathing and coughing techniques, encouraging relaxation techniques, or administering antianxiety medications. |

Enhanced Breathing and Coughing Techniques

In addition to oxygen therapy and the interventions listed in Table 8.2b, there are several techniques a nurse can teach a patient to use to enhance their breathing and coughing. These techniques include pursed-lip breathing, incentive spirometry, coughing and deep breathing, and the huffing technique. Additionally, vibratory positive expiratory pressure (PEP) therapy can be incorporated in collaboration with a respiratory therapist.

Pursed-lip Breathing

Pursed-lip breathing is a technique that decreases dyspnea by teaching people to control their oxygenation and ventilation. See Figure 8.5[30] for an illustration of pursed-lip breathing. The technique teaches a person to inhale through the nose and exhale through the mouth at a slow, controlled flow. This type of exhalation gives the person a puckered or pursed-lip appearance. By prolonging the expiratory phase of respiration, a small amount of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is created in the airways that helps to keep them open so that more air can be exhaled. This subsequently reduces air trapping that commonly occurs in conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Pursed-lip breathing relieves the feeling of shortness of breath, decreases the work of breathing, and improves gas exchange. People also regain a sense of control over their breathing while simultaneously increasing their relaxation.[31]

Incentive Spirometry

An incentive spirometer is a medical device commonly prescribed after surgery to expand the lungs, reduce the buildup of fluid in the lungs, and prevent pneumonia. See Figure 8.6[32] for an image of a patient using an incentive spirometer. While sitting upright, if possible, the patient should place the mouthpiece in their mouth and create a tight seal with their lips around it. They should breathe in slowly and as deeply as possible through the tubing with the goal of raising the piston to their prescribed level. The resistance indicator on the right side should be monitored to ensure they are not breathing in too quickly. The patient should attempt to hold their breath for as long as possible (at least 5 seconds) and then exhale and rest for a few seconds. Coughing is expected. Encourage the patient to expel the mucus and not swallow it. This technique should be repeated by the patient 10 times every hour while awake.[33] The nurse may delegate this intervention to unlicensed assistive personnel, but the frequency in which it is completed and the volume achieved should be documented and monitored by the nurse.

Coughing and Deep Breathing

Coughing and deep breathing is a breathing technique similar to incentive spirometry but no device is required. The patient is encouraged to take deep, slow breaths and then exhale slowly. After each set of breaths, the patient should cough. This technique is repeated 3 to 5 times every hour.

Huffing Technique

The huffing technique is helpful to teach patients who have difficulty coughing. Teach the patient to inhale with a medium-sized breath and then make a sound like “ha” to push the air out quickly with the mouth slightly open.

Vibratory PEP Therapy

Vibratory Positive Expiratory Pressure (PEP) Therapy uses handheld devices such as flutter valves or Acapella devices for patients who need assistance in clearing mucus from their airways. These devices require a prescription and are used in collaboration with a respiratory therapist or advanced health care provider. To use vibratory PEP therapy, the patient should sit up, take a deep breath, and blow into the device. A flutter valve within the device creates vibrations that help break up the mucus so the patient can cough and spit it out. Additionally, a small amount of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is created in the airways that helps to keep them open so that more air can be exhaled. See the supplementary video below regarding how to use the flutter valve device.

View this video on Using a Flutter Valve Device (Acapella).[34]