Nursing Process

4.3 Assessment

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Assessment is the first step of the nursing process (and the first Standard of Practice set by the American Nurses Association). This standard is defined as, “The registered nurse collects pertinent data and information relative to the health care consumer’s health or the situation.” This includes collecting “pertinent data related to the health and quality of life in a systematic, ongoing manner, with compassion and respect for the wholeness, inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person, including but not limited to, demographics, environmental and occupational exposures, social determinants of health, health disparities, physical, functional, psychosocial, emotional, cognitive, spiritual/transpersonal, sexual, sociocultural, age-related, environmental, and lifestyle/economic assessments.”[1]

Nurses assess patients to gather clues, make generalizations, and diagnose human responses to health conditions and life processes. Patient data is considered either subjective or objective, and it can be collected from multiple sources.

Subjective Assessment Data

Subjective data is information obtained from the patient and/or family members and offers important cues from their perspectives. When documenting subjective data stated by a patient, it should be in quotation marks and start with verbiage such as, The patient reports. It is vital for the nurse to establish rapport with a patient to obtain accurate, valuable subjective data regarding the mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects of their condition.

There are two types of subjective information, primary and secondary. Primary data is information provided directly by the patient. Patients are the best source of information about their bodies and feelings, and the nurse who actively listens to a patient will often learn valuable information while also promoting a sense of well-being. Information collected from a family member, chart, or other sources is known as secondary data. Family members can provide important information, especially for individuals with memory impairments, infants, children, or when patients are unable to speak for themselves.

See Figure 4.5[2] for an illustration of a nurse obtaining subjective data and establishing rapport after obtaining permission from the patient to sit on the bed.

Example. An example of documented subjective data obtained from a patient assessment is, “The patient reports, ‘My pain is a level 2 on a 1-10 scale.’”

Objective Assessment Data

Objective data is anything that you can observe through your sense of hearing, sight, smell, and touch while assessing the patient. Objective data is reproducible, meaning another person can easily obtain the same data. Examples of objective data are vital signs, physical examination findings, and laboratory results. See Figure 4.6[3] for an image of a nurse performing a physical examination.

Example. An example of documented objective data is, “The patient’s radial pulse is 58 and regular, and their skin feels warm and dry.”

Sources of Assessment Data

There are three sources of assessment data: interview, physical examination, and review of laboratory or diagnostic test results.

Interviewing

Interviewing includes asking the patient questions, listening, and observing verbal and nonverbal communication. Reviewing the chart prior to interviewing the patient may eliminate redundancy in the interview process and allows the nurse to hone in on the most significant areas of concern or need for clarification. However, if information in the chart does not make sense or is incomplete, the nurse should use the interview process to verify data with the patient.

After performing patient identification, the best way to initiate a caring relationship is to introduce yourself to the patient and explain your role. Share the purpose of your interview and the approximate time it will take. When beginning an interview, it may be helpful to start with questions related to the patient’s medical diagnoses to gather information about how they have affected the patient’s functioning, relationships, and lifestyle. Listen carefully and ask for clarification when something isn’t clear to you. Patients may not volunteer important information because they don’t realize it is important for their care. By using critical thinking and active listening, you may discover valuable cues that are important to provide safe, quality nursing care. Sometimes nursing students can feel uncomfortable having difficult conversations or asking personal questions due to generational or other cultural differences. Don’t shy away from asking about information that is important to know for safe patient care. Most patients will be grateful that you cared enough to ask and listen.

Be alert and attentive to how the patient answers questions, as well as when they do not answer a question. Nonverbal communication and body language can be cues to important information that requires further investigation. A keen sense of observation is important. To avoid making inappropriate inferences, the nurse should validate any cues. For example, a nurse may make an inference that a patient is depressed when the patient avoids making eye contact during an interview. However, upon further questioning, the nurse may discover that the patient’s cultural background believes direct eye contact to be disrespectful and this is why they are avoiding eye contact. To read more information about communicating with patients, review the “Communication” chapter of this book.

Physical Examination

A physical examination is a systematic data collection method of the body that uses the techniques of inspection, auscultation, palpation, and percussion. Inspection is the observation of a patient’s anatomical structures. Auscultation is listening to sounds, such as heart, lung, and bowel sounds, created by organs using a stethoscope. Palpation is the use of touch to evaluate organs for size, location, or tenderness. Percussion is an advanced physical examination technique typically performed by providers where body parts are tapped with fingers to determine their size and if fluid is present. Detailed physical examination procedures of various body systems can be found in the Open RN Nursing Skills textbook with a head-to-toe checklist in Appendix C. Physical examination also includes the collection and analysis of vital signs.

Registered Nurses (RNs) complete the initial physical examination and analyze the findings as part of the nursing process. Collection of follow-up physical examination data can be delegated to Licensed Practical Nurses/Licensed Vocational Nurses (LPNs/LVNs), or measurements such as vital signs and weight may be delegated to trained Unlicensed Assistive Personnel (UAP) when appropriate to do so. However, the RN remains responsible for supervising these tasks, analyzing the findings, and ensuring they are documented .

A physical examination can be performed as a comprehensive, head-to-toe assessment or as a focused assessment related to a particular condition or problem. Assessment data is documented in the patient’s Electronic Medical Record (EMR), an electronic version of the patient’s medical chart.

Reviewing Laboratory and Diagnostic Test Results

Reviewing laboratory and diagnostic test results provides relevant and useful information related to the needs of the patient. Understanding how normal and abnormal results affect patient care is important when implementing the nursing care plan and administering provider prescriptions. If results cause concern, it is the nurse’s responsibility to notify the provider and verify the appropriateness of prescriptions based on the patient’s current status before implementing them.

Types of Assessments

Several types of nursing assessment are used in clinical practice:

- Primary Survey: Used during every patient encounter to briefly evaluate level of consciousness, airway, breathing, and circulation and implement emergency care if needed.

- Admission Assessment: A comprehensive assessment completed when a patient is admitted to a facility that involves assessing a large amount of information using an organized approach.

- Ongoing Assessment: In acute care agencies such as hospitals, a head-to-toe assessment is completed and documented at least once every shift. Any changes in patient condition are reported to the health care provider.

- Focused Assessment: Focused assessments are used to reevaluate the status of a previously diagnosed problem.

- Time-lapsed Reassessment: Time-lapsed reassessments are used in long-term care facilities when three or more months have elapsed since the previous assessment to evaluate progress on previously identified outcomes.[4]

Putting It Together

Review Scenario C in the following box to apply concepts of assessment to a patient scenario.

Scenario C[5]

Ms. J. is a 74-year-old woman who is admitted directly to the medical unit after visiting her physician because of shortness of breath, increased swelling in her ankles and calves, and fatigue. Her medical history includes hypertension (30 years), coronary artery disease (18 years), heart failure (2 years), and type 2 diabetes (14 years). She takes 81 mg of aspirin every day, metoprolol 50 mg twice a day, furosemide 40 mg every day, and metformin 2,000 mg every day.

Ms. J.’s vital sign values on admission were as follows:

- Blood Pressure: 162/96 mm Hg

- Heart Rate: 88 beats/min

- Oxygen Saturation: 91% on room air

- Respiratory Rate: 28 breaths/minute

- Temperature: 97.8 degrees F orally

Her weight is up 10 pounds since the last office visit three weeks prior. The patient states, “I am so short of breath” and “My ankles are so swollen I have to wear my house slippers.” Ms. J. also shares, “I am so tired and weak that I can’t get out of the house to shop for groceries,” and “Sometimes I’m afraid to get out of bed because I get so dizzy.” She confides, “I would like to learn more about my health so I can take better care of myself.”

The physical assessment findings of Ms. J. are bilateral basilar crackles in the lungs and bilateral 2+ pitting edema of the ankles and feet. Laboratory results indicate a decreased serum potassium level of 3.4 mEq/L.

As the nurse completes the physical assessment, the patient’s daughter enters the room. She confides, “We are so worried about mom living at home by herself when she is so tired all the time!”

Critical Thinking Questions

- Identify subjective data.

- Identify objective data.

- Provide an example of secondary data.

Answers are located in the Answer Key at the end of the book.

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- "361341143-huge.jpg” by Monkey Business Images is used under license from Shutterstock.com ↵

- “13394660711603.jpg” by CDC/ Amanda Mills is in the Public Domain ↵

- Gordon, M. (2008). Assess notes: Nursing assessment and diagnostic reasoning. F.A. Davis Company. ↵

- “grandmother-1546855_960_720.jpg” by vendie4u is licensed under CC0 ↵

Before learning about cognitive impairment, it is important to understand the physiological processes of normal growth and development. Growth includes physical changes that occur during the development of an individual beginning at the time of conception. Development encompasses these biological changes, as well as social and cognitive changes that occur continuously throughout our lives. Cognition starts at birth and continues throughout the life span. See Figure 6.1[1] for an image of the human life cycle.

There are multiple factors that affect human cognitive development. While there are expected milestones along the way, cognitive development encompasses several different skills that develop at different rates. Cognition takes the form of many paths leading to unique developmental ends. Each human has their own individual experience that influences development of intelligence and reasoning as they interact with one another. With these unique experiences, everyone has a memory of feelings and events that is exclusive to them.[2]

Developmental Stages

As newborns, we learn behavior and communication to help us to interact with the world around us and to fulfill our needs. For example, crying provides communication to cue parents or caregivers about a newborn’s needs. The human brain undergoes tremendous development throughout the first year of life. As infants receive and experience input from the environment, they begin to interact with the individuals around them as they learn and grow.

Jean Piaget, a well-known cognitive development theorist, noted that children explore the world as they attempt to make sense of their experiences. His theory explains that humans move from one stage to another as they seek cognitive equilibrium and mental balance. There are four stages in Piaget’s theory of development that occur in children from all cultures:

- The first stage is the Sensorimotor period. It extends from birth to approximately two years and is a period of rapid cognitive growth. During this period, infants develop an understanding of the world by coordinating sensory experiences (seeing, hearing) with motor actions (reaching, touching). The main development during the sensorimotor stage is the understanding that objects exist and events occur in the world independently of one's own actions.[3] Infants develop an understanding of what they want and what they must do to have their needs met. They begin to understand language used by those around them to make needs met.

- Infants progress from the Sensorimotor period to a Pre-Operational period in their toddler years. This continues through early school age years. This is the time frame when children learn to think in images and symbols. Play is an important part of cognitive development during this period.

- Older school age children (age 7 years to 11 years) enter a Concrete Operations period. They learn to think in terms of processes and can understand that there is more than one perspective when discussing a concept.[4] This stage is considered a major turning point in the child's cognitive development because it marks the beginning of logical or operational thought.

- Adolescents transition to the Formal Operations stage around age 12 as they become self-conscious and egocentric. As adolescents enter this stage, they gain the ability to think in an abstract manner by manipulating ideas in their head. Moving toward adulthood, this further develops into the ability to critically reason.[5],[6]

Cognitive impairments in children range from mild impairment in these specific operations to profound intellectual impairments leading to minimal independent functioning. Cognitive impairment is a term used to describe impairment in mental processes that drive how an individual understands and acts in the world, affecting the acquisition of information and knowledge. The following areas are domains of cognitive functioning:

- Attention

- Decision-making

- General knowledge

- Judgment

- Language

- Memory

- Perception

- Planning

- Reasoning

- Visuospatial[7]

Intellectual disability (formerly referred to as mental retardation) is a diagnostic term that describes intellectual and adaptive functioning deficits identified during the developmental period. In the United States, the developmental period refers to the span of time prior to the age 18. Children with intellectual disabilities may demonstrate a delay in developmental milestones (e.g., sitting, speaking, walking) or demonstrate mild cognitive impairments that may not be identified until school age. Intellectual disability is typically nonprogressive and lifelong. It is diagnosed by multidisciplinary clinical assessments and standardized testing and is treated with a multidisciplinary treatment plan that maximizes quality of life.[8] See Figure 6.2[9] for an image of an adolescent with an intellectual disability participating in a Special Olympics event.

Adults and Older Adults

There are several physical changes that occur in the brain due to aging. The structure of neurons change, including a decreased number and length of dendrites, loss of dendritic spines, a decrease in the number of axons, an increase in axons with segmental demyelination, and a significant loss of synapses. Loss of synapse is a key marker of aging in the nervous system. These physical changes occur in older adults experiencing cognitive impairments, as well as in those who do not.[10] See Figure 6.3[11] of an older adult experiencing typical physical changes of aging.

It is a common myth that all individuals experience cognitive impairments as they age. Many people are afraid of growing older because they fear becoming forgetful, confused, and incapable of managing their daily life leading to incorrect perceptions and ageism. Ageism refers to stereotyping older individuals because of their age. Losing language skills, becoming unable to make decisions appropriately, and being disoriented to self or surroundings are not normal aging changes.

Dementia, Delirium, and Depression

If changes in cognition in adults do occur, a complete assessment is required to determine the underlying cause of the change and if it is caused by an acute or chronic condition. For example, dementia is a chronic condition that affects cognition whereas depression and delirium can cause acute confusion with a similar clinical appearance to dementia.

Dementia

Dementia is a chronic condition of impaired cognition, caused by brain disease or injury, and marked by personality changes, memory deficits, and impaired reasoning. Dementia can be caused by a group of conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, frontal-temporal dementia, and Lewy body disease. Clinical manifestations of dementia include forgetfulness, impaired social skills, and impaired decision-making and thinking abilities that interfere with daily living. It is gradual, progressive, and irreversible.[12] While dementia is not reversible, appropriate assessment and nursing care improve the safety and quality of life for those affected by dementia.

As dementia progresses and cognition continues to deteriorate, nursing care must be individualized to meet the needs of the patient and family. Providing patient safety and maintaining quality of life while meeting physical and psychosocial needs are important aspects of nursing care. Unsafe behaviors put individuals with dementia at increased risk for injury. These unsafe or inappropriate behaviors often occur due to the patient having a need or emotion without the ability to express it, such as pain, hunger, anxiety, or the need to use the bathroom. The patient’s family/caregivers require education and support to recognize that behaviors are often a symptom of dementia and/or a communication of a need and to help them to best meet the needs of their family member.[13]

Delirium

Delirium is an acute state of cognitive impairment that typically occurs suddenly due to a physiological cause, such as infection, hypoxia, electrolyte imbalances, drug effects, or other acute brain injury. Sensory overload, excess stress, and sleep deprivation can also cause delirium. Hospitalized older adults are at increased risk for developing delirium, especially if they have been previously diagnosed with dementia. One third of patients aged 70 years or older exhibit delirium during their hospitalization. Delirium is the most common surgical complication for older adults, occurring in 15 to 25% of patients after major elective surgery and up to 50% of patients experiencing hip-fracture repair or cardiac surgery.[14]

The symptoms of delirium usually start suddenly, over a few hours or a few days, and they often come and go. Common symptoms include the following:

- Changes in alertness (usually most alert in the morning and decreased at night)

- Changing levels of consciousness

- Confusion

- Disorganized thinking or talking in a way that do not make sense

- Disrupted sleep patterns or sleepiness

- Emotional changes: anger, agitation, depression, irritability, overexcitement

- Hallucinations and delusions

- Incontinence

- Memory problems, especially with short-term memory

- Trouble concentrating[15]

Delirium and dementia have similar symptoms, so it can be hard to tell them apart. They can also occur together.

Nurses must closely monitor the cognitive function of all patients and promptly report any changes in mental status to the health care provider. The provider will take a medical history, perform a physical and neurological examination, perform mental status testing, and may order diagnostic tests based on the patient’s medical history. After the cause of delirium is determined, treatment is targeted to the cause to reverse the effects. See Figure 6.4[16] for an illustration of an older adult experiencing delirium.

General interventions to prevent and treat delirium in older adults are as follows:

- Control the environment. Make sure that the room is quiet and well-lit, have clocks or calendars in view, and encourage family members to visit.

- Ensure a safe environment with the call light within reach and side rails up as indicated.

- Administer prescribed medications, including those that control aggression or agitation, and pain relievers if there is pain.

- Ensure the patient has their glasses, hearing aids, or other assistive devices for communication in place. Lack of assistive sensory devices can worsen delirium.

- Avoid sedatives. Sedatives can worsen delirium.

- Assign the same staff for patient care when possible.[18]

Depression

Depression is a brain disorder with a variety of causes, including genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological factors. It is a commonly untreated condition in older adults that can result in impaired cognition and difficulty in making decisions. It is likely to occur in response to major life events involving health and loved ones. Having other chronic health problems, such as diabetes, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, cancer, heart disease, and kidney disease, increases the likelihood for depression in older adults and can cause the loss of their ability to maintain independence.[19] See Figure 6.5[20] for an illustration of an older adult experiencing symptoms of depression.

Symptoms of depression include the following:

- Feeling sad or "empty"

- Loss of interest in favorite activities

- Overeating or not wanting to eat at all

- Not being able to sleep or sleeping too much

- Feeling very tired

- Feeling hopeless, irritable, anxious, or guilty

- Aches, pains, headaches, cramps, or digestive problems

- Thoughts of death or suicide[21]

Depression is treatable with medication and psychotherapy. However, older adults have an increased risk for suicide, with the suicide rates for individuals over age 85 years the second highest rate overall. Nurses should provide appropriate screening to detect potential signs of depression as an important part of promoting health for older adults.

Comparison of Three Conditions

When an older adult presents with confusion, determining if it is caused by delirium, dementia, depression, or a combination of these conditions can pose many challenges to the health care team. It is helpful to know the patient’s baseline mental status from a family member, caregiver, or previous health care records. If a patient’s baseline mental status is not known, it is an important patient safety consideration to assume that confusion is caused by delirium with a thorough assessment for underlying causes.[22] See Table 6.2 for a comparison of symptoms of dementia, delirium, and depression.[23]

Table 6.2 Comparison of Dementia, Delirium, and Depression[24]

| Dementia | Delirium | Depression | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset | Vague, insidious onset; symptoms progress slowly | Sudden onset over hours and days with fluctuations | Onset often rapid with identifiable trigger or life event such as bereavement |

| Symptoms | Symptoms may go unnoticed for years. May attempt to hide cognitive problems or may be unaware of them. Often disoriented to time, place, and person. Impaired short-term memory and information processing. Confusion is often worse in the evening (referred to as "sundowning") | Often disoriented to time, place, and person. Impaired short-term memory loss and information processing. Confusion is often worse in the evening | Obvious at early stages and often worse in the morning. Can include subjective complaints of memory loss |

| Consciousness | Normal | Impaired attention/alertness | Normal |

| Mental State | Possibly labile mood. Consistently decreased cognitive performance | Emotional lability with anxiety, fear, depression, aggression. Variable cognitive performance | Distressed/unhappy. Variable cognitive performance |

| Delusions/Hallucinations | Common | Common | Rare |

| Psychomotor Disturbance | Psychomotor disturbance in later stages | Psychomotor disturbance present - hyperactive, purposeless, or apathetic | Slowed psychomotor status in severe depression |

Alzheimer’s disease is an irreversible, progressive brain disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills and eventually the ability to carry out the simplest tasks. It is the most common cause of dementia. In most people with Alzheimer’s disease, symptoms first appear in their mid-60s. One in ten Americans age 65 and older has Alzheimer's disease.[25]

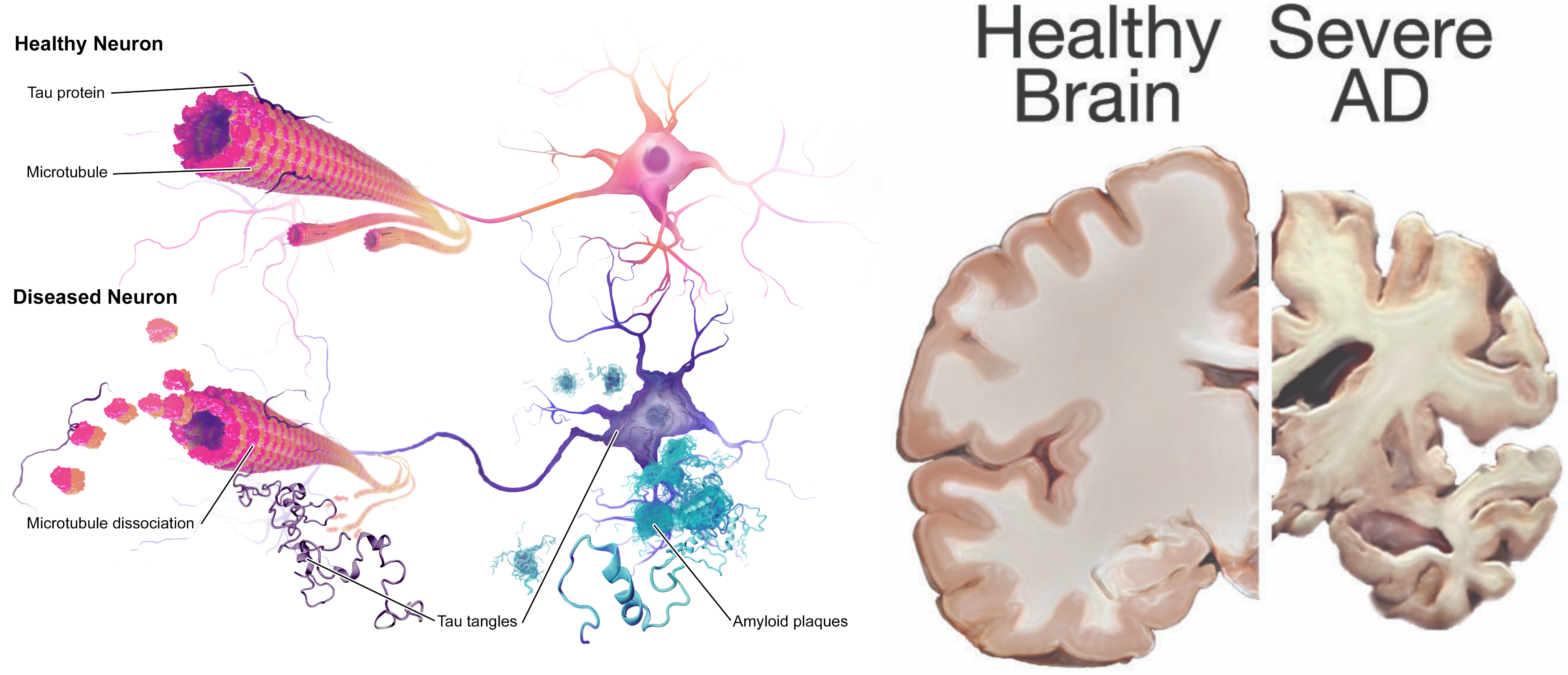

Scientists continue to unravel the complex brain changes involved in the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease. It is thought that changes in the brain may begin a decade or more before memory and other cognitive problems appear. Abnormal deposits of proteins form amyloid plaques and tau tangles throughout the brain. Previously healthy neurons stop functioning, lose connections with other neurons, and die. The damage initially appears to take place in the hippocampus and cortex, the parts of the brain essential in forming memories. As more neurons die, additional parts of the brain are affected and begin to shrink. By the final stage of Alzheimer’s, damage is widespread, and brain tissue has shrunk significantly.[26] See Figure 6.6[27] for an image of the changes occurring in the brain during Alzheimer’s disease.

View a video of the changes that occur in the brain during Alzheimer’s disease:[28]

Symptoms of Early Alzheimer’s Disease

There are ten symptoms of early Alzheimer’s disease:

- Forgetting recently learned information that disrupts daily life. This includes forgetting important dates or events, asking the same questions over and over, and increasingly needing to rely on memory aids (e.g., reminder notes or electronic devices) or family members for things they used to handle on their own. This is different than a typical age-related change of sometimes forgetting names or appointments, but remembering them later.

- Challenges in planning or solving problems. This includes changes in an individual’s ability to develop and follow a plan or work with numbers. For example, they may have trouble following a familiar recipe or keeping track of monthly bills. They may have difficulty concentrating and take much longer to do things than they did before. This is different from a typical age-related change of making occasional errors when managing finances or household bills.

- Difficulty completing familiar tasks. This includes trouble driving to a familiar location, organizing a grocery list, or remembering the rules of a favorite game. This symptom is different from a typical age-related change of occasionally needing help to use microwave settings or to record a TV show.

- Confusion with time or place. This includes losing track of dates, seasons, and the passage of time. Individuals may have trouble understanding something if it is not happening immediately. Sometimes they may forget where they are or how they got there. This symptom is different from a typical age-related change of forgetting the date or day of the week but figuring it out later.

- Trouble understanding visual images and spatial relationships. Vision problems that include difficulty judging distance, determining color or contrast, or causing issues with balance or driving can be symptoms of Alzeheimer’s. This is different from a typical age-related change of blurred vision related to presbyopia or cataracts. (See the “Sensory Impairments” chapter for more information on common vision problems.)

- New problems with words in speaking or writing. Individuals with Alzheimer's may have trouble following or joining a conversation. They may stop in the middle of a conversation and have no idea how to continue or they may repeat themselves. They may struggle with vocabulary, have trouble naming a familiar object, or use the wrong name (e.g., calling a "watch" a "hand-clock"). This is different from a typical age-related change of having trouble finding the right word.

- Misplacing things and losing the ability to retrace steps. A person with Alzheimer's disease may put things in unusual places. They may lose things and be unable to go back over their steps to find them again. They may accuse others of stealing, especially as the disease progresses. This is different from a typical age-related change of misplacing things from time to time and retracing steps to find them.

- Decreased or poor judgment. Individuals with Alzheimer’s may experience changes in judgment or decision-making. For example, they may use poor judgment when dealing with money or pay less attention to grooming or keeping themselves clean. This is different from a typical age-related change of making a bad decision or mistake once in a while, like neglecting to change the oil in the car.

- Withdrawal from work or social activities. A person living with Alzheimer’s disease may experience changes in the ability to hold or follow a conversation. As a result, he or she may withdraw from hobbies, social activities, or other engagements. They may have trouble keeping up with a favorite team or activity. This is different from a typical age-related change of sometimes feeling uninterested in family or social obligations.

- Changes in mood and personality. Individuals living with Alzheimer’s may experience mood and personality changes. They can become confused, suspicious, depressed, fearful, or anxious. They may be easily upset at home, with friends, or when out of their comfort zone. This is different from a typical age-related change of developing very specific ways of doing things and becoming irritable when a routine is disrupted.[29]

Three Stages of Dementia

There are three stages of dementia: early, moderate, and advanced. Early stages of dementia include the ten symptoms previously discussed. Patients with moderate dementia require additional assistance with reminders to eat, wash, and use the restroom. They may not recognize family and friends. Behavioral symptoms such as wandering, getting lost, hallucinations, delusions, and repetitive behavior may occur. Patients living at home may engage in risky behavior, such as leaving the house in clothing inappropriate for weather conditions or leaving on the stove burners. Patients with advanced dementia require full assistance in washing, dressing, eating, and toileting. They often have urinary and bowel incontinence. Their gait becomes shuffled or unsteady. There may be increased aggressive behavior, disinhibition, or inappropriate laughing. Eventually they have difficulty eating, swallowing, and speaking, and seizures may develop.[30] See Figure 6.7[31] of a patient with dementia requiring assistance with dressing.

There is no single diagnostic test that can determine if a person has Alzheimer’s disease. Health care providers use a patient’s medical history, mental status tests, physical and neurological exams, and diagnostic tests to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia. During the neurological exam, reflexes, coordination, muscle tone and strength, eye movement, speech, and sensation are tested.

Mental status testing evaluates memory, thinking, and simple problem-solving abilities. Some tests are brief, whereas others can be more time-intensive and complex. These tests give an overall sense of whether a person is aware of their symptoms; knows the date, time, and place where they are; can remember a short list of words; and if they can follow instructions and do simple calculations. The Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE) and Mini-Cog test are two commonly used assessments.

During the MMSE, a health professional asks a patient a series of questions designed to test a range of everyday mental skills. The maximum MMSE score is 30 points. A score of 20 to 24 suggests mild dementia, 13 to 20 suggests moderate dementia, and less than 12 indicates severe dementia. On average, the MMSE score of a person with Alzheimer's declines about two to four points each year.

During the Mini-Cog, a person is asked to complete two tasks: remember and then later repeat the names of three common objects and draw a face of a clock showing all 12 numbers in the right places with the time indicated as specified by the examiner. The results of this brief test determine if further evaluation is needed. In addition to assessing mental status, the health care provider evaluates a person's sense of well-being to detect depression or other mood disorders that can cause memory problems, loss of interest in life, and other symptoms that can overlap with dementia.

Diagnostic testing for Alzheimer's disease may include structural imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT). These tests are primarily used to rule out other conditions that can cause symptoms similar to Alzheimer's but require different treatment. For example, structural imaging can reveal brain tumors, evidence of strokes, damage from head trauma, or a buildup of fluid in the brain.[32]

Treatments

While there is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease, there are medications to help lessen symptoms of memory loss and confusion and interventions to manage common symptomatic behaviors.

Medications

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved two types of medications, cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine, to treat the cognitive symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (memory loss, confusion, and problems with thinking and reasoning). As Alzheimer’s progresses, brain cells die and connections among cells are lost, causing cognitive symptoms to worsen. While current medications cannot stop the damage Alzheimer’s causes to brain cells, they may help lessen or stabilize symptoms for a limited time by affecting certain chemicals involved in carrying messages among the brain's nerve cells. Sometimes both types of medications are prescribed together.

Cholinesterase inhibitors are prescribed to treat early to moderate symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease related to memory, thinking, language, judgment, and other thought processes. Cholinesterase inhibitors prevent the breakdown of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter that is vital for learning and memory. It supports communication among nerve cells by keeping acetylcholine high and delays or slows the worsening of symptoms. Effectiveness varies from person to person, and the medications are generally well-tolerated. If side effects occur, they commonly include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and increased frequency of bowel movements. These three cholinesterase inhibitors are commonly prescribed:

- Donepezil (Aricept), approved to treat all stages of Alzheimer’s disease

- Galantamine (Razadyne), approved for mild-to-moderate stages

- Rivastigmine (Exelon), approved for mild-to-moderate stages

Memantine (Namenda) and a combination of memantine and donepezil (Namzaric) are approved by the FDA for treatment of moderate to severe Alzheimer’s. Memantine is prescribed to improve memory, attention, reasoning, language, and the ability to perform simple tasks. Memantine regulates the activity of glutamate, a chemical involved in information processing, storage, and retrieval. It improves mental function and the ability to perform daily activities for some people, but it can cause side effects, including headache, constipation, confusion, and dizziness.

Other medications may be prescribed to treat specific symptoms of depression, anxiety, or psychosis. However, the decision to use an antipsychotic drug must be considered with extreme caution. Research has shown that these drugs are associated with an increased risk of stroke and death in older adults with dementia. The FDA has ordered manufacturers to label such drugs with a “Black Box” warning about their risks and a reminder that they are not approved to treat dementia symptoms. Individuals with dementia should use antipsychotic medications only under one of the following conditions:

- Behavioral symptoms are due to mania or psychosis.

- The symptoms present a danger to the person or others.

- The person is experiencing inconsolable or persistent distress, a significant decline in function, or substantial difficulty receiving needed care.

Antipsychotic medications should not be used to sedate or restrain persons with dementia. The minimum dosage should be used for the minimum amount of time possible, and nurses should carefully monitor for adverse side effects and report them to the health care provider.[33]

Interventions for Symptomatic Behavior

Many people find the behavioral changes caused by Alzheimer's disease to be the most challenging and distressing effect of the disease. The chief cause of behavioral symptoms is the progressive deterioration of brain cells. However, medication, environmental influences, and some medical conditions can also cause symptoms or make them worse.

In the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, people may experience behavior and personality changes, such as irritability, anxiety, and depression. In later stages, other symptoms may occur, including the following:

- Aggression and anger

- Anxiety and agitation

- General emotional distress

- Physical or verbal outbursts

- Restlessness, pacing, or shredding paper or tissues

- Hallucinations (seeing, hearing, or feeling things that are not really there)

- Delusions (firmly held beliefs in things that are not true)

- Sleep issues and sundowning

Sundowning is restlessness, agitation, irritability, or confusion that typically begins or worsens as daylight begins to fade and can continue into the night, making it hard for patients with Alzheimer's to sleep. Being too tired can increase late-afternoon and early-evening restlessness. Tips to manage sundowning are as follows:[34]

- Take them outside or expose them to bright light in the morning to reset their circadian rhythm.

- Do not plan too many activities during the day. A full schedule can be overtiring.

- Make early evening a quiet time of day. Play soothing music or ask a family member or friend to call during this time.

- Close the curtains or blinds at dusk to minimize shadows and the confusion they may cause.

- Reduce noise, clutter, or the number of people in the room.

- Do not serve coffee, cola, or other drinks with caffeine late in the day.

Aggressive Behaviors

Aggressive behaviors may be verbal or physical. They can occur suddenly, with no apparent reason, or result from a frustrating situation. While aggression can be hard to cope with, understanding this is a symptom of Alzheimer’s disease and the person with Alzheimer's or dementia is not acting this way on purpose can help. See Figure 6.8[35] for an image of a resident with dementia demonstrating aggressive verbal behavior.

Aggression can be caused by many factors including physical discomfort, environmental factors, and poor communication. If the person with Alzheimer's is aggressive, consider what might be contributing to the change in behavior.

Physical Discomfort

- Is the person able to let you know that he or she is experiencing physical pain? It is not uncommon for persons with Alzheimer's or other dementias to have urinary tract or other infections. Due to their loss of cognitive function, they are unable to articulate or identify the cause of physical discomfort and, therefore, may express it through physical aggression.

- Is the person tired because of inadequate rest or sleep?

- Is the person hungry or thirsty?

- Are medications causing side effects? Side effects are especially likely to occur when individuals are taking multiple medications for several health conditions.

Environmental Factors

- Is the person overstimulated by loud noises, an overactive environment, or physical clutter? Large crowds or being surrounded by unfamiliar people — even within one's own home — can be overstimulating for a person with dementia.

- Does the person feel lost?

- What time of day is the person most alert? Most people function better during a certain time of day; typically mornings are best. Consider the time of day when making appointments or scheduling activities. Choose a time when you know the person is most alert and best able to process new information or surroundings.

Poor Communication

- Are your instructions simple and easy to understand?

- Are you asking too many questions or making too many statements at once?

- Is the person picking up on your own stress or irritability?

Techniques for Response

There are many therapeutic methods for a nurse or caregiver to respond to aggressive behaviors displayed by a person with dementia. The following are some methods that can be used with aggressive behavior:

- Begin by trying to identify the immediate cause of the behavior. Think about what happened right before the reaction that may have triggered the behavior. Rule out pain as the cause of the behavior. Pain can trigger aggressive behavior for a person with dementia.

- Focus on the person’s feelings, not the facts. Look for the feelings behind the specific words or actions.

- Don't get upset. Be positive and reassuring and speak slowly in a soft tone.

- Limit distractions. Examine the person's surroundings, and adapt them to avoid future triggers.

- Implement a relaxing activity. Try music, massage, or exercise to help soothe the person.

- Shift the focus to another activity. The immediate situation or activity may have unintentionally caused the aggressive response, so try a different approach.

- Take a break if needed. If the person is in a safe environment and you are able, walk away and take a moment for emotions to cool.

- Ensure safety! Make sure you and the person are safe. If these interventions do not successfully calm down the person, seek assistance from others. If it is an emergency situation, call 911 and be sure to tell the responders the person has dementia that causes them to act aggressively.

When educating caregivers about responding to aggressive behaviors, encourage them to share their experience with others, such as face-to-face support groups, where they can share response strategies they have tried and also get more ideas from other caregivers.

Anxiety and Agitation

A person with Alzheimer's may feel anxious or agitated. They may become restless, causing a need to move around or pace or become upset in certain places or when focused on specific details. See Figure 6.9[36] for an illustration of an older adult feeling the need to move around. Anxiety and agitation can be caused by several medical conditions, medication interactions, or by any circumstances that worsen the person's ability to think. Ultimately, the person with dementia is biologically experiencing a profound loss of their ability to negotiate new information and stimuli. It is a direct result of the disease. Situations that may lead to agitation can include moving to a new residence or nursing home; changes in environment, such as travel, hospitalization, or the presence of houseguests; changes in caregiver arrangements; misperceived threats; or fear and fatigue resulting from trying to make sense out of a confusing world.

Interventions to prevent and treat agitation include the following:

- Create a calm environment and remove stressors. This may involve moving the person to a safer or quieter place or offering a security object, rest, or privacy. Providing soothing rituals and limiting caffeine use are also helpful.

- Avoid environmental triggers. Noise, glare, and background distraction (such as having the television on) can act as triggers.

- Monitor personal comfort. Check for pain, hunger, thirst, constipation, full bladder, fatigue, infections, and skin irritation. Make sure the room is at a comfortable temperature. Be sensitive to the person’s fears, misperceived threats, and frustration with expressing what is wanted.

- Simplify tasks and routines.

- Find outlets for the person's energy. The person may be looking for something to do. Provide an opportunity for exercise such as going for a walk or putting on music and dancing.

Techniques for Response

If a patient with dementia becomes anxious or agitated, consider these potential interventions:

- Back off and ask permission before performing care tasks. Use calm, positive statements, slow down, add lighting, and provide reassurance. Offer guided choices between two options when possible. Focus on pleasant events and try to limit stimulation.

- Use effective language. When speaking, try phrases such as, “May I help you? Do you have time to help me? You're safe here. Everything is under control. I apologize. I'm sorry that you are upset. I know it's hard. I will stay with you until you feel better.”

- Listen to the person’s frustration. Find out what may be causing the agitation, and try to understand.

- Check yourself. Do not raise your voice, show alarm or offense, or corner, crowd, restrain, criticize, ignore, or argue with the person. Take care not to make sudden movements out of the person's view.

If the person’s anxiety or agitation does not improve using these techniques, notify the provider to rule out physiological causes or medication-related side effects.

Hallucinations

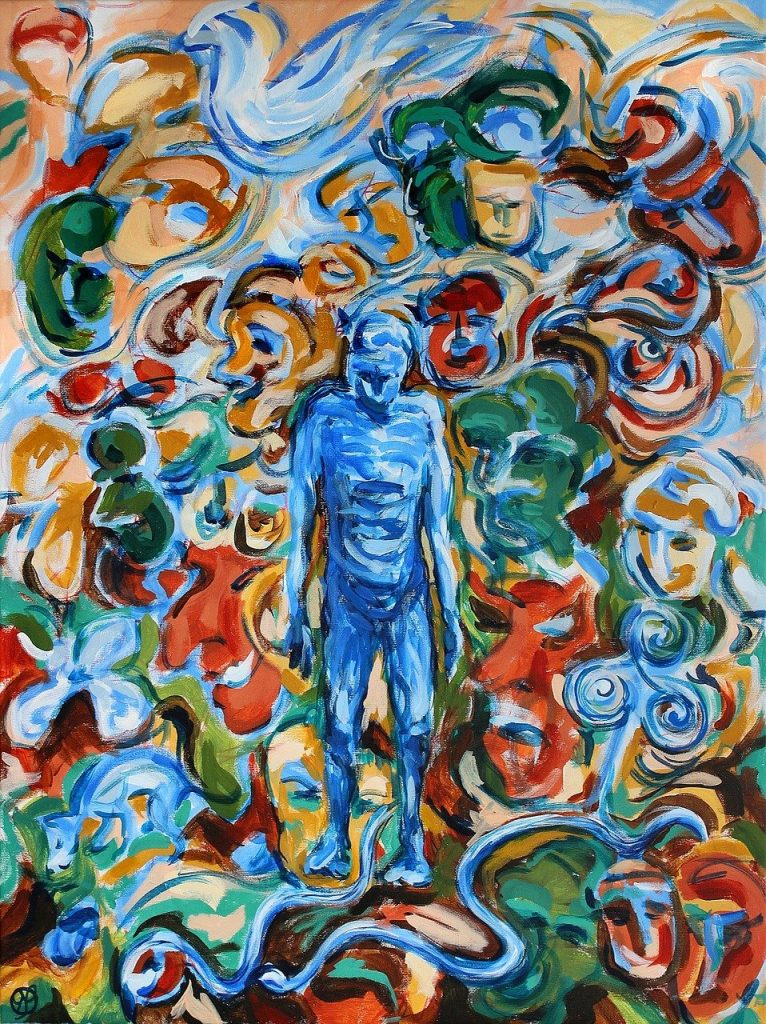

When a person with dementia experiences hallucinations, they may see, hear, smell, taste, or feel something that isn't there. Some hallucinations may be frightening, while others may involve ordinary visions of people, situations, or objects from the past. Alzheimer's and other dementias are not the only cause of hallucinations. Other causes of hallucinations include schizophrenia; physical problems, such as kidney or bladder infections, dehydration, or intense pain; alcohol or drug abuse; eyesight or hearing problems; and medications. See Figure 6.10[37] for an illustration of hallucinations experienced by a person with dementia.

If a person with dementia begins hallucinating, notify the health care provider to rule out other possible causes and to determine if medication is needed. It may also help to have the person's eyesight or hearing checked. If these strategies fail and symptoms are severe, medication may be prescribed. While antipsychotic medications can be effective in some situations, they are associated with an increased risk of stroke and death in older adults with dementia and must be used carefully.

Techniques for Response

When responding to a patient with dementia experiencing hallucinations, be cautious. First, assess the situation and determine whether the hallucination is a problem for the person or for you. Is the hallucination upsetting? Is it leading the person to do something dangerous? Is the sight of an unfamiliar face causing the person to become frightened? If so, react calmly and quickly with reassuring words and a comforting touch. Do not argue with the person about what he or she sees or hears. If the behavior is not dangerous, there may not be a need to intervene.

- Offer reassurance. Respond in a calm, supportive manner. You may want to respond with, "Don't worry. I'm here. I'll protect you. I'll take care of you." Gentle patting may turn the person's attention toward you and reduce the hallucination.

- Acknowledge the feelings behind the hallucination and try to find out what the hallucination means to the individual. You might want to say, "It sounds as if you're worried" or "This must be frightening for you."

- Use distractions. Suggest a walk or move to another room. Frightening hallucinations often subside in well-lit areas where other people are present. Try to turn the person's attention to music, conversation, or activities they enjoy.

- Respond honestly. If the person asks you about a hallucination or delusion, be honest. For example, if he or she asks, "Do you see the spider on the wall?," you can respond, "I know you see something, but I don't see it." This way you're not denying what the person sees or hears and avoiding escalating their agitation.

- Modify the environment. Check for sounds that might be misinterpreted, such as noise from a television or an air conditioner. Look for lighting that casts shadows, reflections, or distortions on the surfaces of floors, walls, and furniture. Turn on lights to reduce shadows. Cover mirrors with a cloth or remove them if the person thinks that he or she is looking at a stranger.

Sundowning

Sundowning is increased confusion, anxiety, agitation, pacing, and disorientation in patients with dementia that typically begins at dusk and continues throughout the night. Although the exact cause of sundowning and sleep disorders in people with Alzheimer’s disease is unknown, these changes result from the disease’s impact on the brain. There are several factors that may contribute to sleep disturbances and sundowning:

- Mental and physical exhaustion from a full day trying to keep up with an unfamiliar or confusing environment.

- An upset in the "internal body clock," causing a biological mix-up between day and night.

- Reduced lighting causing shadows and misinterpretation is seen, causing agitation.

- Nonverbal behaviors of others, especially if stress or frustration is present.

- Disorientation due to the inability to separate dreams from reality when sleeping.

- Decreased need for sleep, a common condition among older adults.[38]

There are several interventions that nurses and caregivers can implement to help manage sleep issues and sundowning:

- Promote plenty of rest.

- Encourage a regular routine of waking up, eating meals, and going to bed.

- When possible and appropriate, include walks or time outside in the sunlight.

- Make notes about what happens before sundowning events and try to identify triggers.

- Reduce stimulation during the evening hours (e.g., TV, doing chores, loud music, etc.). These distractions may add to the person’s confusion.

- Offer a larger meal at lunch and keep the evening meal lighter.

- Keep the home environment well-lit in the evening. Adequate lighting may reduce the person’s confusion.

- Do not physically restrain the person; it can make agitation worse.

- Try to identify activities that are soothing to the person, such as listening to calming music, looking at photographs, or watching a favorite movie.

- Take a walk with the person to help reduce his or her restlessness.

- Consider the best times of day for administering medication; consult with the prescribing provider or pharmacist as needed.

- Limit daytime naps if the person has trouble sleeping at night.

- Reduce or avoid alcohol, caffeine, and nicotine that can affect the ability to sleep.

- Discuss the situation with the provider when behavioral interventions and environmental changes do not work. Additional medications may be prescribed.

Caregiver Role Strain

Eighty-three percent of the help provided to people living with dementia in their homes in the United States comes from family members, friends, or other unpaid caregivers. Approximately one quarter of dementia caregivers are also "sandwich generation" caregivers — meaning that they care not only for an aging parent, but also for children under age 18. Dementia can take a devastating toll on caregivers. Compared with caregivers of people without dementia, twice as many caregivers of people with dementia indicate substantial emotional, financial, and physical difficulties.[39] See Figure 6.11[40] of an image of a caregiver daughter caring for her mother with dementia.

The caregivers of patients with dementia frequently report experiencing high levels of stress that often eventually impact their health and well-being. Nurses should monitor caregivers for these symptoms of stress:

- Denial about the disease and its effect on the person who has been diagnosed. For example, the caregiver might say, “I know Mom is going to get better.”

- Anger at the person with Alzheimer’s or frustration that he or she can’t do the things they used to be able to do. For example, the caregiver might say, “He knows how to get dressed — he’s just being stubborn.”

- Social withdrawal from friends and activities. For example, the caregiver may say, “I don’t care about visiting with my friends anymore.”

- Anxiety about the future and facing another day. For example, the caregiver might say, “What happens when he needs more care than I can provide?”

- Depression or decreased ability to cope. For example, the caregiver might say, “I just don't care anymore.”

- Exhaustion that makes it difficult for them to complete necessary daily tasks. For example, the caregiver might say, “I'm too tired to prepare meals.”

- Sleeplessness caused by concerns. For example, the caregiver might say, “What if she wanders out of the house or falls and hurts herself?”

- Irritability, moodiness, or negative responses.

- Lack of concentration that makes it difficult to perform familiar tasks. For example, the caregiver might say, “I was so busy; I forgot my appointment.”

- Health problems that begin to take a mental and physical toll. For example, the caregiver might say, “I can't remember the last time I felt good.”

Nurses should monitor for these signs of caregiver stress and provide information about community resources. (See additional information about community resources below.) Caregivers should be encouraged to take good care of themselves by visiting their health care provider, eating well, exercising, and getting plenty of rest. It is helpful to remind them that “taking care of yourself and being healthy can help you be a better caregiver.” It is helpful to teach them relaxation techniques, such as relaxation breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, visualization, and meditation.

Caregivers should also be educated about additional care options, such as adult day care, respite care, residential facilities, or hospice care. Adult day centers offer people with dementia and other chronic illnesses the opportunity to be social and to participate in activities in a safe environment, while also giving their caregivers the opportunity to work, run errands, or take a break. Respite care can be provided at home (by a volunteer or paid service) or in a care setting, such as adult day care or residential facility, to provide the caregiver a much-needed break. If the person with Alzheimer's or other dementia prefers a communal living environment or requires more care than can be safely provided at home, a residential facility may be the best option for providing care. Different types of facilities provide different levels of care, depending on the person's needs. Hospice care focuses on providing comfort and dignity at the end of life; it involves care and support services that can be of great benefit to people in the final stages of dementia and their families.

Read about alternative care options and caregiver support at the Alzheimer Association webpage.

Community Resources

Local Alzheimer's Association chapters can connect families and caregivers with the resources they need to cope with the challenges of caring for individuals with Alzheimer's.

- Find a chapter in your community by visiting the Find Your Local Chapter web page.

- The Alzheimer’s Association 24/7 Helpline (800.272.3900) is available around the clock, 365 days a year. Through this free service, specialists and master’s-level clinicians offer confidential support and information to people living with dementia, caregivers, families, and the public.

- The Alzheimer’s Association has a free virtual library web page devoted to resources that increase knowledge about Alzheimer's and other dementias.[41]