Nursing Process

4.2 Basic Concepts

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Before learning how to use the nursing process, it is important to understand some basic concepts related to critical thinking and nursing practice. Let’s take a deeper look at how nurses think.

Critical Thinking and Clinical Reasoning

Nurses make decisions while providing patient care by using critical thinking and clinical reasoning. Critical thinking is a broad term used in nursing that includes “reasoning about clinical issues such as teamwork, collaboration, and streamlining workflow.”[1] Using critical thinking means that nurses take extra steps to maintain patient safety and don’t just “follow orders.” It also means the accuracy of patient information is validated and plans for caring for patients are based on their needs, current clinical practice, and research.

“Critical thinkers” possess certain attitudes that foster rational thinking. These attitudes are as follows:

- Independence of thought: Thinking on your own

- Fair-mindedness: Treating every viewpoint in an unbiased, unprejudiced way

- Insight into egocentricity and sociocentricity: Thinking of the greater good and not just thinking of yourself. Knowing when you are thinking of yourself (egocentricity) and when you are thinking or acting for the greater good (sociocentricity)

- Intellectual humility: Recognizing your intellectual limitations and abilities

- Nonjudgmental: Using professional ethical standards and not basing your judgments on your own personal or moral standards

- Integrity: Being honest and demonstrating strong moral principles

- Perseverance: Persisting in doing something despite it being difficult

- Confidence: Believing in yourself to complete a task or activity

- Interest in exploring thoughts and feelings: Wanting to explore different ways of knowing

- Curiosity: Asking “why” and wanting to know more

Clinical reasoning is defined as, “A complex cognitive process that uses formal and informal thinking strategies to gather and analyze patient information, evaluate the significance of this information, and weigh alternative actions.”[2] To make sound judgments about patient care, nurses must generate alternatives, weigh them against the evidence, and choose the best course of action. The ability to clinically reason develops over time and is based on knowledge and experience.[3]

Inductive and Deductive Reasoning and Clinical Judgment

Inductive and deductive reasoning are important critical thinking skills. They help the nurse use clinical judgment when implementing the nursing process.

Inductive reasoning involves noticing cues, making generalizations, and creating hypotheses. Cues are data that fall outside of expected findings that give the nurse a hint or indication of a patient’s potential problem or condition. The nurse organizes these cues into patterns and creates a generalization. A generalization is a judgment formed from a set of facts, cues, and observations and is similar to gathering pieces of a jigsaw puzzle into patterns until the whole picture becomes more clear. Based on generalizations created from patterns of data, the nurse creates a hypothesis regarding a patient problem. A hypothesis is a proposed explanation for a situation. It attempts to explain the “why” behind the problem that is occurring. If a “why” is identified, then a solution can begin to be explored.

No one can draw conclusions without first noticing cues. Paying close attention to a patient, the environment, and interactions with family members is critical for inductive reasoning. As you work to improve your inductive reasoning, begin by first noticing details about the things around you. A nurse is similar to the detective looking for cues in Figure 4.1.[4] Be mindful of your five primary senses: the things that you hear, feel, smell, taste, and see. Nurses need strong inductive reasoning patterns and be able to take action quickly, especially in emergency situations. They can see how certain objects or events form a pattern (i.e., generalization) that indicates a common problem (i.e., hypothesis).

Example: A nurse assesses a patient and finds the surgical incision site is red, warm, and tender to the touch. The nurse recognizes these cues form a pattern of signs of infection and creates a hypothesis that the incision has become infected. The provider is notified of the patient’s change in condition, and a new prescription is received for an antibiotic. This is an example of the use of inductive reasoning in nursing practice.

Deductive reasoning is another type of critical thinking that is referred to as “top-down thinking.” Deductive reasoning relies on using a general standard or rule to create a strategy. Nurses use standards set by their state’s Nurse Practice Act, federal regulations, the American Nursing Association, professional organizations, and their employer to make decisions about patient care and solve problems.

Example: Based on research findings, hospital leaders determine patients recover more quickly if they receive adequate rest. The hospital creates a policy for quiet zones at night by initiating no overhead paging, promoting low-speaking voices by staff, and reducing lighting in the hallways. (See Figure 4.2).[5] The nurse further implements this policy by organizing care for patients that promotes periods of uninterrupted rest at night. This is an example of deductive thinking because the intervention is applied to all patients regardless if they have difficulty sleeping or not.

Clinical judgment is the result of critical thinking and clinical reasoning using inductive and deductive reasoning. Clinical judgment is defined by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) as, “The observed outcome of critical thinking and decision-making. It uses nursing knowledge to observe and assess presenting situations, identify a prioritized patient concern, and generate the best possible evidence-based solutions in order to deliver safe patient care.” [6] The NCSBN administers the national licensure exam (NCLEX) that measures nursing clinical judgment and decision-making ability of prospective entry-level nurses to assure safe and competent nursing care by licensed nurses.

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is defined by the American Nurses Association (ANA) as, “A lifelong problem-solving approach that integrates the best evidence from well-designed research studies and evidence-based theories; clinical expertise and evidence from assessment of the health care consumer’s history and condition, as well as health care resources; and patient, family, group, community, and population preferences and values.”[7]

Nursing Process

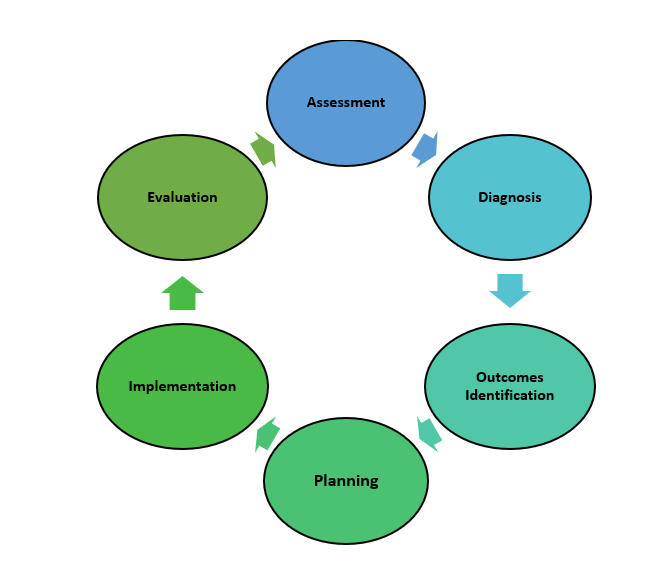

The nursing process is a critical thinking model based on a systematic approach to patient-centered care. Nurses use the nursing process to perform clinical reasoning and make clinical judgments when providing patient care. The nursing process is based on the Standards of Professional Nursing Practice established by the American Nurses Association (ANA). These standards are authoritative statements of the actions and behaviors that all registered nurses, regardless of role, population, specialty, and setting, are expected to perform competently.[8] The mnemonic ADOPIE is an easy way to remember the ANA Standards and the nursing process. Each letter refers to the six components of the nursing process: Assessment, Diagnosis, Outcomes Identification, Planning, Implementation, and Evaluation.

The nursing process is a continuous, cyclic process that is constantly adapting to the patient’s current health status. See Figure 4.3[9] for an illustration of the nursing process.

Review Scenario A in the following box for an example of a nurse using the nursing process while providing patient care.

Patient Scenario A: Using the Nursing Process[10]

A hospitalized patient has a prescription to receive Lasix 80mg IV every morning for a medical diagnosis of heart failure. During the morning assessment, the nurse notes that the patient has a blood pressure of 98/60, heart rate of 100, respirations of 18, and a temperature of 98.7F. The nurse reviews the medical record for the patient’s vital signs baseline and observes the blood pressure trend is around 110/70 and the heart rate in the 80s. The nurse recognizes these cues form a pattern related to fluid imbalance and hypothesizes that the patient may be dehydrated. The nurse gathers additional information and notes the patient’s weight has decreased 4 pounds since yesterday. The nurse talks with the patient and validates the hypothesis when the patient reports that their mouth feels like cotton and they feel light-headed. By using critical thinking and clinical judgment, the nurse diagnoses the patient with the nursing diagnosis Fluid Volume Deficit and establishes outcomes for reestablishing fluid balance. The nurse withholds the administration of IV Lasix and contacts the health care provider to discuss the patient’s current fluid status. After contacting the provider, the nurse initiates additional nursing interventions to promote oral intake and closely monitor hydration status. By the end of the shift, the nurse evaluates the patient status and determines that fluid balance has been restored.

In Scenario A, the nurse is using clinical judgment and not just “following orders” to administer the Lasix as scheduled. The nurse assesses the patient, recognizes cues, creates a generalization and hypothesis regarding the fluid status, plans and implements nursing interventions, and evaluates the outcome. Additionally, the nurse promotes patient safety by contacting the provider before administering a medication that could cause harm to the patient at this time.

The ANA’s Standards of Professional Nursing Practice associated with each component of the nursing process are described below.

Assessment

The “Assessment” Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse collects pertinent data and information relative to the health care consumer’s health or the situation.”[11] A registered nurse uses a systematic method to collect and analyze patient data. Assessment includes physiological data, as well as psychological, sociocultural, spiritual, economic, and lifestyle data. For example, a nurse’s assessment of a hospitalized patient in pain includes the patient’s response to pain, such as the inability to get out of bed, refusal to eat, withdrawal from family members, or anger directed at hospital staff.[12]

The “Assessment” component of the nursing process is further described in the “Assessment” section of this chapter.

Diagnosis

The “Diagnosis” Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse analyzes the assessment data to determine actual or potential diagnoses, problems, and issues.”[13] A nursing diagnosis is the nurse’s clinical judgment about the client's response to actual or potential health conditions or needs. Nursing diagnoses are the bases for the nurse’s care plan and are different than medical diagnoses.[14]

The “Diagnosis” component of the nursing process is further described in the “Diagnosis” section of this chapter.

Outcomes Identification

The “Outcomes Identification” Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse identifies expected outcomes for a plan individualized to the health care consumer or the situation.”[15] The nurse sets measurable and achievable short- and long-term goals and specific outcomes in collaboration with the patient based on their assessment data and nursing diagnoses.

The “Outcomes Identification” component of the nursing process is further described in the “Outcomes Identification” section of this chapter.

Planning

The “Planning” Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse develops a collaborative plan encompassing strategies to achieve expected outcomes.”[16] Assessment data, diagnoses, and goals are used to select evidence-based nursing interventions customized to each patient’s needs and concerns. Goals, expected outcomes, and nursing interventions are documented in the patient’s nursing care plan so that nurses, as well as other health professionals, have access to it for continuity of care.[17]

The “Planning” component of the nursing process is further described in the “Planning” section of this chapter.

Nursing Care Plans

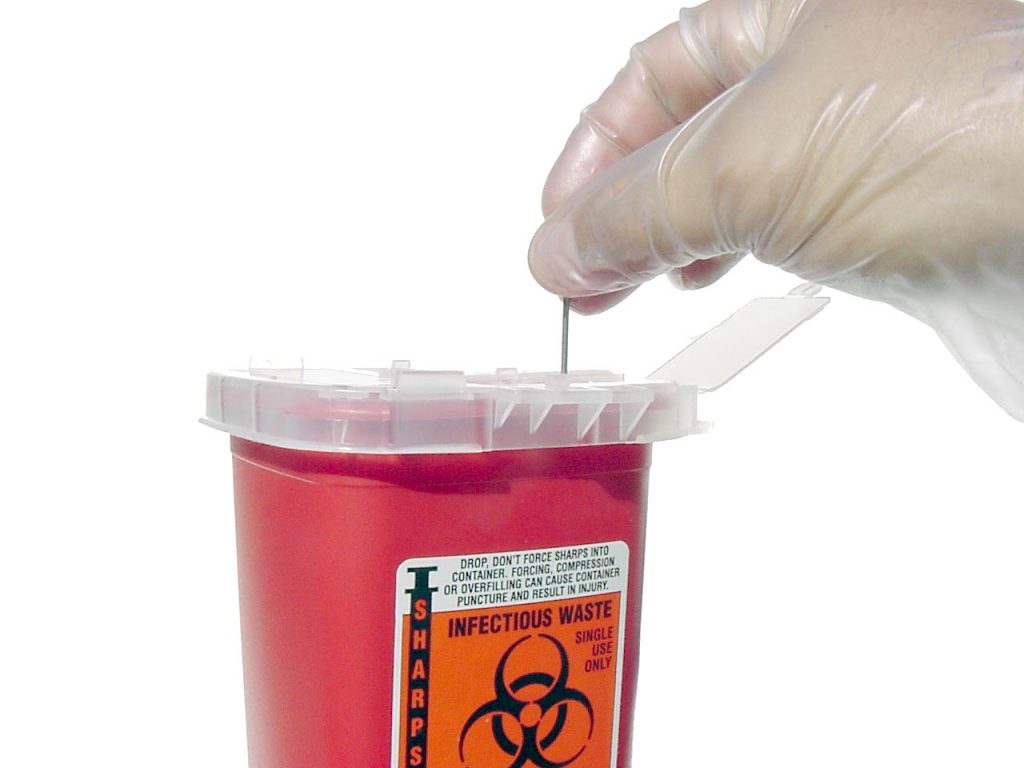

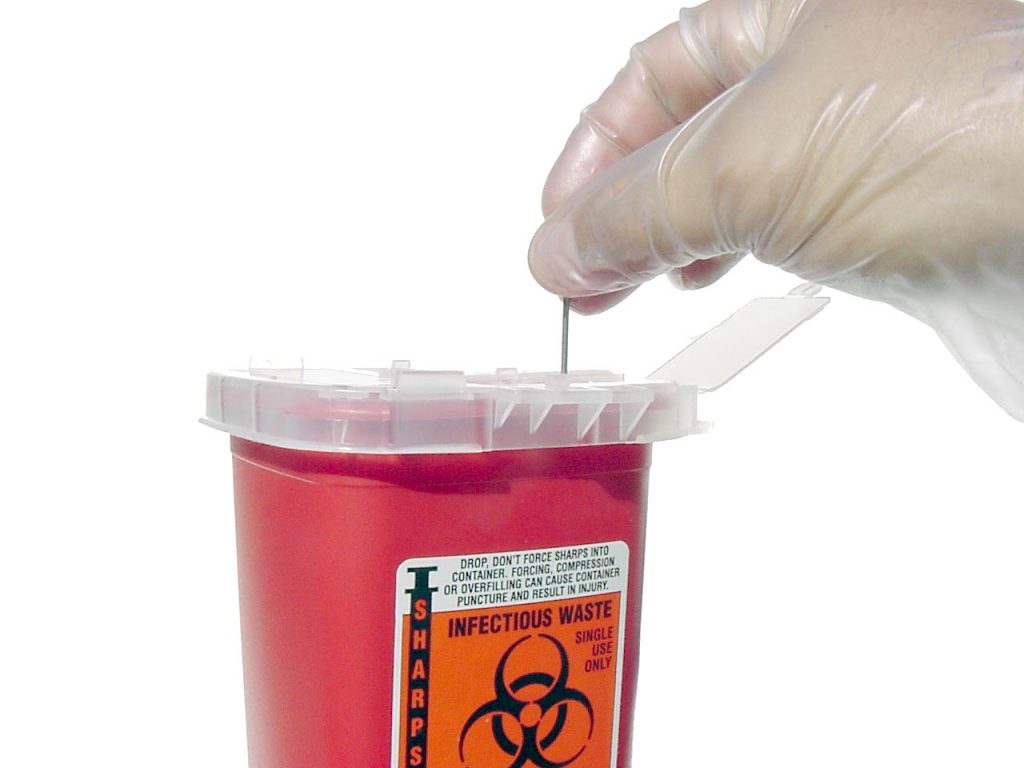

Creating nursing care plans is a part of the “Planning” step of the nursing process. A nursing care plan is a type of documentation that demonstrates the individualized planning and delivery of nursing care for each specific patient using the nursing process. Registered nurses (RNs) create nursing care plans so that the care provided to the patient across shifts is consistent among health care personnel. Some interventions can be delegated to Licensed Practical Nurses (LPNs) or trained Unlicensed Assistive Personnel (UAPs) with the RN’s supervision. Developing nursing care plans and implementing appropriate delegation are further discussed under the “Planning” and “Implementing” sections of this chapter.

Implementation

The “Implementation” Standard of Practice is defined as, “The nurse implements the identified plan.”[18] Nursing interventions are implemented or delegated with supervision according to the care plan to assure continuity of care across multiple nurses and health professionals caring for the patient. Interventions are also documented in the patient’s electronic medical record as they are completed.[19]

The “Implementation” Standard of Professional Practice also includes the subcategories “Coordination of Care” and “Health Teaching and Health Promotion” to promote health and a safe environment.[20]

The “Implementation” component of the nursing process is further described in the “Implementation” section of this chapter.

Evaluation

The “Evaluation” Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse evaluates progress toward attainment of goals and outcomes.”[21] During evaluation, nurses assess the patient and compare the findings against the initial assessment to determine the effectiveness of the interventions and overall nursing care plan. Both the patient’s status and the effectiveness of the nursing care must be continuously evaluated and modified as needed.[22]

The “Evaluation” component of the nursing process is further described in the “Evaluation” section of this chapter.

Benefits of Using the Nursing Process

Using the nursing process has many benefits for nurses, patients, and other members of the health care team. The benefits of using the nursing process include the following:

- Promotes quality patient care

- Decreases omissions and duplications

- Provides a guide for all staff involved to provide consistent and responsive care

- Encourages collaborative management of a patient’s health care problems

- Improves patient safety

- Improves patient satisfaction

- Identifies a patient’s goals and strategies to attain them

- Increases the likelihood of achieving positive patient outcomes

- Saves time, energy, and frustration by creating a care plan or path to follow

By using these components of the nursing process as a critical thinking model, nurses plan interventions customized to the patient’s needs, plan outcomes and interventions, and determine whether those actions are effective in meeting the patient’s needs. In the remaining sections of this chapter, we will take an in-depth look at each of these components of the nursing process. Using the nursing process and implementing evidence-based practices are referred to as the “science of nursing.” Let’s review concepts related to the “art of nursing” while providing holistic care in a caring manner using the nursing process.

Holistic Nursing Care

The American Nurses Association (ANA) recently updated the definition of nursing as, “Nursing integrates the art and science of caring and focuses on the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and human functioning; prevention of illness and injury; facilitation of healing; and alleviation of suffering through compassionate presence. Nursing is the diagnosis and treatment of human responses and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, groups, communities, and populations in the recognition of the connection of all humanity.”[23]

The ANA further describes nursing is a learned profession built on a core body of knowledge that integrates both the art and science of nursing. The art of nursing is defined as, “Unconditionally accepting the humanity of others, respecting their need for dignity and worth, while providing compassionate, comforting care.”[24]

Nurses care for individuals holistically, including their emotional, spiritual, psychosocial, cultural, and physical needs. They consider problems, issues, and needs that the person experiences as a part of a family and a community as they use the nursing process. Review a scenario illustrating holistic nursing care provided to a patient and their family in the following box.

Holistic Nursing Care Scenario

A single mother brings her child to the emergency room for ear pain and a fever. The physician diagnoses the child with an ear infection and prescribes an antibiotic. The mother is advised to make a follow-up appointment with their primary provider in two weeks. While providing discharge teaching, the nurse discovers that the family is unable to afford the expensive antibiotic prescribed and cannot find a primary care provider in their community they can reach by a bus route. The nurse asks a social worker to speak with the mother about affordable health insurance options and available providers in her community and follows up with the prescribing physician to obtain a prescription for a less expensive generic antibiotic. In this manner, the nurse provides holistic care and advocates for improved health for the child and their family.

Caring and the Nursing Process

The American Nurses Association (ANA) states, “The act of caring is foundational to the practice of nursing.”[25] Successful use of the nursing process requires the development of a care relationship with the patient. A care relationship is a mutual relationship that requires the development of trust between both parties. This trust is often referred to as the development of rapport and underlies the art of nursing. While establishing a caring relationship, the whole person is assessed, including the individual’s beliefs, values, and attitudes, while also acknowledging the vulnerability and dignity of the patient and family. Assessing and caring for the whole person takes into account the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects of being a human being.[26] Caring interventions can be demonstrated in simple gestures such as active listening, making eye contact, touching, and verbal reassurances while also respecting and being sensitive to the care recipient’s cultural beliefs and meanings associated with caring behaviors.[27] See Figure 4.4[28] for an image of a nurse using touch as a therapeutic communication technique to communicate caring.

Dr. Jean Watson is a nurse theorist who has published many works on the art and science of caring in the nursing profession. Her theory of human caring sought to balance the cure orientation of medicine, giving nursing its unique disciplinary, scientific, and professional standing with itself and the public. Dr. Watson’s caring philosophy encourages nurses to be authentically present with their patients while creating a healing environment.[29]

Now that we have discussed basic concepts related to the nursing process, let’s look more deeply at each component of the nursing process in the following sections.

- Klenke-Borgmann, L., Cantrell, M. A., & Mariani, B. (2020). Nurse educator’s guide to clinical judgment: A review of conceptualization, measurement, and development. Nursing Education Perspectives, 41(4), 215-221. ↵

- Klenke-Borgmann, L., Cantrell, M. A., & Mariani, B. (2020). Nurse educator’s guide to clinical judgment: A review of conceptualization, measurement, and development. Nursing Education Perspectives, 41(4), 215-221. ↵

- Powers, L., Pagel, J., & Herron, E. (2020). Nurse preceptors and new graduate success. American Nurse Journal, 15(7), 37-39. ↵

- “The Detective” by paurian is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- “In the Quiet Zone…” by C.O.D. Library is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 ↵

- NCSBN. (n.d.). NCSBN clinical judgment model. https://www.ncsbn.org/14798.htm ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- “The Nursing Process” by Kim Ernstmeyer at Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Patient Image in LTC.JPG” by ARISE project is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.). The nursing process. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/workforce/what-is-nursing/the-nursing-process/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.). The nursing process. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/workforce/what-is-nursing/the-nursing-process/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.). The nursing process. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/workforce/what-is-nursing/the-nursing-process/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (3rd ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.) The nursing process. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/workforce/what-is-nursing/the-nursing-process/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.). The nursing process. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/workforce/what-is-nursing/the-nursing-process/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- Walivaara, B., Savenstedt, S., & Axelsson, K. (2013). Caring relationships in home-based nursing care - registered nurses’ experiences. The Open Journal of Nursing, 7, 89-95. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3722540/pdf/TONURSJ-7-89.pdf ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- “hospice-1793998_1280.jpg” by truthseeker08 is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Watson Caring Science Institute. (n.d.). Watson Caring Science Institute. Jean Watson, PHD, RN, AHN-BC, FAAN, (LL-AAN). https://www.watsoncaringscience.org/jean-bio/ ↵

To promote safety for patients of all ages, nurses should be knowledgeable about safety risks according to age and developmental stages because the types and frequencies of accidents vary among age groups. Information from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) regarding safety tips for each age group is summarized in the following subsections.[1]

Infants and Preschoolers

Drowning is the leading cause of death in children aged 1-3 years. Motor vehicle accidents, falls, choking, and accidental poisoning are also safety concerns for this age group. Infants and toddlers are curious, but they lack the judgement to recognize the dangers of their actions, so childproofing the home and providing adult supervision are essential for this developmental age group.[2] See Figure 5.7[3] for an image of an infant car seat used to protect infants in the event of a motor vehicle accident. Nurses help educate parents about the proper use, positioning, and installation of car seats.

School-Aged Children

In children aged 4-11, motor vehicle injuries are a major cause of unintentional injury, along with drowning and poisoning. This age group is more aware of dangers and limitations, but adult supervision is still important. The nurse should educate parents of school-aged children about safety seats, booster seats, or shoulder seat belts while riding in the car.[4]

Bicycle accidents are also a common concern in this age group. Many bike accidents involve the head or face because of the lack of helmet use. Nurses provide health teaching to school-aged children regarding bicycle safety and helmet use. See Figure 5.8[5] for an image of a girl wearing a bike helmet.

Because this age group is beginning to enjoy more independence, basic instructions and education on how to recognize and respond to potentially dangerous situations with strangers should also be provided. Parents should also be educated about the AMBER alert system that can be activated if a child is missing and believed to be kidnapped or in danger. This AMBER alert system uses the resources of law enforcement and the media to notify the public about a possible abduction or a missing child in danger.[6]

Nurses must also be aware of signs of maltreatment and child abuse because millions of children are affected each year. Child abuse includes physical, sexual, emotional abuse, and neglect. According to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP), after abuse or violence, many children develop mental health problems, including depression and posttraumatic stress disorder. These children may also have serious medical problems, learning problems, and problems getting along with friends and family members. Every state has laws that require health care professionals to report suspected child abuse no matter what form this abuse takes.[7]

Adolescents

Motor vehicle accidents are the number one cause of death for adolescents. Teens aged 16-19 are three times more likely to be in a fatal crash than drivers older than age 20. Adolescent males are twice as likely to die in a motor vehicle accident than females of the same age. Texting while driving is a common cause of distracted driving and accidents in adolescents. Because much of an adolescent’s time is spent away from the home, it is difficult for parents to control many of the decisions that adolescents make. Nurses educate teenagers to use seat belts, obey speed limits, and never use a cell phone or text while driving.[8] See Figure 5.9[9] for an image reminding teenage drivers to not text and drive.

Traumatic brain injuries (TBI) may occur in this age group due to participation in sports and recreation-related activities. TBI results from a blow, jolt, or hit to the head that causes a disruption in blood function or flow to the brain. Nurses should always be alert for indications of a concussion when a sports injury has occurred. Signs of a concussion requiring immediate medical attention include the following:

- Headache, vomiting, balance problems, fatigue, or drowsiness

- A dazed and confused appearance or difficulty concentrating or remembering; confusion

- Emotional irritability, nervousness, or a change in personality

The CDC has comprehensive information and education materials for parents, coaches, players, and health care providers as part of their “Heads Up” program.[10]

Substance abuse is another significant concern in the adolescent population and includes substances such as tobacco, alcohol, illicit drugs, prescription medication, over-the-counter medications, and bath salts. The National Institutes of Health provides many resources for educating teens and their parents about substance abuse.[11]

Adults

Intimate partner violence and substance abuse are common safety issues in the adult population.

Intimate Partner Violence

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is widespread in the United States and is the most prevalent adult safety issue. Intimate partner violence includes physical or sexual violence, stalking, and psychological or coercive aggression by current or former intimate partners. Victims can be female or male, and sexual orientation can be heterosexual or LGBTQ+. The nurse is often the initial health care professional in contact with a victim of IPV. Prompt recognition of a potential or actual threat to patient and staff safety is crucial. It is often the nurse’s assessment that plays an important role in identifying a patient experiencing IPV. Compassion and understanding are important to show to this vulnerable population. Effective communication is necessary to help victims come forward and share their experiences of abuse. IPV is a complex issue, and the patient may not initially consider leaving the abuser as an option. See Figure 5.10[12] for an image of a sign in a community demonstrating support against domestic violence.

See the following hyperlinks for tools and resources to share with patients experiencing IPV. For example, the Danger Assessment Tool is a self-administered survey that is free to use and is available in several languages.[13] Nurses can refer patients experiencing IPV to the National Center on Domestic Violence, the Trauma and Mental Health database for resources,[14] and the National Domestic Violence Hotline for free, confidential support.[15] Most importantly, nurses should assist patients experiencing IPV to create a safety plan.

View the tools and resources available at these hyperlinks to share with individuals experiencing intimate partner violence:

Substance Abuse

Substance abuse is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a maladaptive pattern of using alcohol and/or drugs despite it causing persistent social, occupational, psychological, or physical problems that can be physically hazardous. Substance abuse continues to be a safety issue that affects adults across all socioeconomic levels. In America over 450,000 people died between 1999 and 2018 as a result of an opioid overdose.[16] The abuse of prescription pain medication (such as oxycontin and fentanyl) and heroin is a national crisis that plagues social and economic welfare. Substance abuse not only affects an individual, but also causes harm to their family members. Early identification of substance abuse, rehabilitation interventions, and continued support are key for helping the individual, as well as their family members, in the recovery process. See Figure 5.11[17] for an image of a heroin needle found in a community setting.

Older Adults

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, falls and motor vehicle accidents are leading causes of injury in older adults. However, several other issues pose significant hazards for this population, such as fires, accidental overdosing on medications (due to poor eyesight and confusion), elder abuse, and financial exploitation.[18] In most reported cases of elder abuse, a caregiver or a person in trusted relationship is the perpetrator. For various reasons such as fear and disappointment, most of these cases go unreported. Abuse, including neglect and exploitation, is experienced by about 1 in 10 people aged 60 and older who live at home. From 2002 to 2016, more than 643,000 older adults were treated in the emergency department for nonfatal assaults and over 19,000 homicides occurred.[19] Read an example of an older adult experiencing financial exploitation in the following box.

Consider the story of John, a 92-year-old male who lost his wife over a year ago and has been lonely ever since. He lives alone in a large home in the country. John hired a repairman to fix his roof. The repairman befriended John, bringing him homemade cookies and pies and even running errands for him. The repairman often stayed for coffee, and the two of them spent time talking about fishing and gardening. The repairman convinced John to take out a reverse mortgage to pay for additional improvements on his home. Then, knowing John’s bank account numbers and login information, the repairman stole $250,000 that John received for his reverse mortgage.

Most victims of elder abuse are frequently seen in the emergency department several times before they are admitted to the hospital. Nurses must be alert to any indications of elder abuse, such as suspicious injuries or behaviors, and report suspected incidents to local adult protective services agencies. Commons signs of elder abuse or maltreatment include the following:[20]

- Bruises, cuts, burns, or broken bones that are unexplainable or suspiciously explained

- Malnourishment or weight loss

- Poor hygiene, an unkempt appearance, unclean clothing, or dirty, matted hair

- Foul odor from clothing or body

- Anxiety, depression, or confusion

- Unexplained transactions or loss of money

- Withdrawal from family members or friends

View additional resources related to elder abuse using the hyperlinks in the following box.

Additional resources for older adults suspected as being victims of elder abuse:

To promote safety for patients of all ages, nurses should be knowledgeable about safety risks according to age and developmental stages because the types and frequencies of accidents vary among age groups. Information from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) regarding safety tips for each age group is summarized in the following subsections.[22]

Infants and Preschoolers

Drowning is the leading cause of death in children aged 1-3 years. Motor vehicle accidents, falls, choking, and accidental poisoning are also safety concerns for this age group. Infants and toddlers are curious, but they lack the judgement to recognize the dangers of their actions, so childproofing the home and providing adult supervision are essential for this developmental age group.[23] See Figure 5.7[24] for an image of an infant car seat used to protect infants in the event of a motor vehicle accident. Nurses help educate parents about the proper use, positioning, and installation of car seats.

School-Aged Children

In children aged 4-11, motor vehicle injuries are a major cause of unintentional injury, along with drowning and poisoning. This age group is more aware of dangers and limitations, but adult supervision is still important. The nurse should educate parents of school-aged children about safety seats, booster seats, or shoulder seat belts while riding in the car.[25]

Bicycle accidents are also a common concern in this age group. Many bike accidents involve the head or face because of the lack of helmet use. Nurses provide health teaching to school-aged children regarding bicycle safety and helmet use. See Figure 5.8[26] for an image of a girl wearing a bike helmet.

Because this age group is beginning to enjoy more independence, basic instructions and education on how to recognize and respond to potentially dangerous situations with strangers should also be provided. Parents should also be educated about the AMBER alert system that can be activated if a child is missing and believed to be kidnapped or in danger. This AMBER alert system uses the resources of law enforcement and the media to notify the public about a possible abduction or a missing child in danger.[27]

Nurses must also be aware of signs of maltreatment and child abuse because millions of children are affected each year. Child abuse includes physical, sexual, emotional abuse, and neglect. According to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP), after abuse or violence, many children develop mental health problems, including depression and posttraumatic stress disorder. These children may also have serious medical problems, learning problems, and problems getting along with friends and family members. Every state has laws that require health care professionals to report suspected child abuse no matter what form this abuse takes.[28]

Adolescents

Motor vehicle accidents are the number one cause of death for adolescents. Teens aged 16-19 are three times more likely to be in a fatal crash than drivers older than age 20. Adolescent males are twice as likely to die in a motor vehicle accident than females of the same age. Texting while driving is a common cause of distracted driving and accidents in adolescents. Because much of an adolescent’s time is spent away from the home, it is difficult for parents to control many of the decisions that adolescents make. Nurses educate teenagers to use seat belts, obey speed limits, and never use a cell phone or text while driving.[29] See Figure 5.9[30] for an image reminding teenage drivers to not text and drive.

Traumatic brain injuries (TBI) may occur in this age group due to participation in sports and recreation-related activities. TBI results from a blow, jolt, or hit to the head that causes a disruption in blood function or flow to the brain. Nurses should always be alert for indications of a concussion when a sports injury has occurred. Signs of a concussion requiring immediate medical attention include the following:

- Headache, vomiting, balance problems, fatigue, or drowsiness

- A dazed and confused appearance or difficulty concentrating or remembering; confusion

- Emotional irritability, nervousness, or a change in personality

The CDC has comprehensive information and education materials for parents, coaches, players, and health care providers as part of their “Heads Up” program.[31]

Substance abuse is another significant concern in the adolescent population and includes substances such as tobacco, alcohol, illicit drugs, prescription medication, over-the-counter medications, and bath salts. The National Institutes of Health provides many resources for educating teens and their parents about substance abuse.[32]

Adults

Intimate partner violence and substance abuse are common safety issues in the adult population.

Intimate Partner Violence

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is widespread in the United States and is the most prevalent adult safety issue. Intimate partner violence includes physical or sexual violence, stalking, and psychological or coercive aggression by current or former intimate partners. Victims can be female or male, and sexual orientation can be heterosexual or LGBTQ+. The nurse is often the initial health care professional in contact with a victim of IPV. Prompt recognition of a potential or actual threat to patient and staff safety is crucial. It is often the nurse’s assessment that plays an important role in identifying a patient experiencing IPV. Compassion and understanding are important to show to this vulnerable population. Effective communication is necessary to help victims come forward and share their experiences of abuse. IPV is a complex issue, and the patient may not initially consider leaving the abuser as an option. See Figure 5.10[33] for an image of a sign in a community demonstrating support against domestic violence.

See the following hyperlinks for tools and resources to share with patients experiencing IPV. For example, the Danger Assessment Tool is a self-administered survey that is free to use and is available in several languages.[34] Nurses can refer patients experiencing IPV to the National Center on Domestic Violence, the Trauma and Mental Health database for resources,[35] and the National Domestic Violence Hotline for free, confidential support.[36] Most importantly, nurses should assist patients experiencing IPV to create a safety plan.

View the tools and resources available at these hyperlinks to share with individuals experiencing intimate partner violence:

Substance Abuse

Substance abuse is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a maladaptive pattern of using alcohol and/or drugs despite it causing persistent social, occupational, psychological, or physical problems that can be physically hazardous. Substance abuse continues to be a safety issue that affects adults across all socioeconomic levels. In America over 450,000 people died between 1999 and 2018 as a result of an opioid overdose.[37] The abuse of prescription pain medication (such as oxycontin and fentanyl) and heroin is a national crisis that plagues social and economic welfare. Substance abuse not only affects an individual, but also causes harm to their family members. Early identification of substance abuse, rehabilitation interventions, and continued support are key for helping the individual, as well as their family members, in the recovery process. See Figure 5.11[38] for an image of a heroin needle found in a community setting.

Older Adults

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, falls and motor vehicle accidents are leading causes of injury in older adults. However, several other issues pose significant hazards for this population, such as fires, accidental overdosing on medications (due to poor eyesight and confusion), elder abuse, and financial exploitation.[39] In most reported cases of elder abuse, a caregiver or a person in trusted relationship is the perpetrator. For various reasons such as fear and disappointment, most of these cases go unreported. Abuse, including neglect and exploitation, is experienced by about 1 in 10 people aged 60 and older who live at home. From 2002 to 2016, more than 643,000 older adults were treated in the emergency department for nonfatal assaults and over 19,000 homicides occurred.[40] Read an example of an older adult experiencing financial exploitation in the following box.

Consider the story of John, a 92-year-old male who lost his wife over a year ago and has been lonely ever since. He lives alone in a large home in the country. John hired a repairman to fix his roof. The repairman befriended John, bringing him homemade cookies and pies and even running errands for him. The repairman often stayed for coffee, and the two of them spent time talking about fishing and gardening. The repairman convinced John to take out a reverse mortgage to pay for additional improvements on his home. Then, knowing John’s bank account numbers and login information, the repairman stole $250,000 that John received for his reverse mortgage.

Most victims of elder abuse are frequently seen in the emergency department several times before they are admitted to the hospital. Nurses must be alert to any indications of elder abuse, such as suspicious injuries or behaviors, and report suspected incidents to local adult protective services agencies. Commons signs of elder abuse or maltreatment include the following:[41]

- Bruises, cuts, burns, or broken bones that are unexplainable or suspiciously explained

- Malnourishment or weight loss

- Poor hygiene, an unkempt appearance, unclean clothing, or dirty, matted hair

- Foul odor from clothing or body

- Anxiety, depression, or confusion

- Unexplained transactions or loss of money

- Withdrawal from family members or friends

View additional resources related to elder abuse using the hyperlinks in the following box.

Additional resources for older adults suspected as being victims of elder abuse:

In addition to promoting safety for patients and their families, it is important for nurses to be aware of safety risks in the environments and to take measures to protect themselves. Common safety risks to nurses include sharps injuries, exposure to blood-borne pathogens, lifting injuries, and lack of personal protective equipment (PPE).

Workplace Safety

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines a healthy environment as a place of physical, mental, and social well-being supporting optimal health and safety. The American Nurses Association (ANA) created the Nurses’ Bill of Rights, a document that sets forth seven basic principles concerning expectations for workplace environments. One of the ANA principles states, “Nurses have the right to a work environment that is safe for themselves and their patients.” [43] Environmental Health is also one of the ANA Standards of Professional Performance. This standard includes "creating a safe and healthy workplace and professional environment."[44]

Preventing Sharps Injuries and Blood-Borne Pathogen Exposure

Exposure to sharps and blood-borne pathogens is a critical safety issue that nurses face in the workplace.[45]Blood-borne pathogen exposure can cause life-threatening illnesses such as hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV. Regulations and laws, such as the Blood-borne Pathogen Standard from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act of 2002, have been effective in significantly reducing sharps injuries and blood exposures among health care workers. Areas covered by these regulations include sharps disposal practices, evaluation and selection of safety-engineered sharps devices and personal protective equipment (PPE), training, record keeping for needlestick injuries, hepatitis B vaccination, and post exposure follow-up. Medical device manufacturers have also played an important role in reducing sharps injury risks to health care workers by developing innovative safety-engineered technology, such as needleless IV access devices.[46] While substantial progress has been made to reduce injuries, preventable sharps injuries and blood exposures continue to occur in health care settings. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), around 385,000 sharps-related injuries occur annually among health care workers in hospitals, but it has been estimated that as many as half of injuries go unreported.[47] See Figure 5.12[48] of a sharps container used to prevent sharps-related injuries.

If you do experience a sharps injury or are exposed to the blood or other body fluid of a patient, follow agency and school policy and immediately follow these steps:

- Wash needlesticks and cuts with soap and water.

- Flush splashes to the nose, mouth, or skin with water.

- Irrigate eyes with clean water, saline, or sterile irrigants.

- Report the incident to your supervisor.

- Immediately seek medical treatment.[49]

Safe Patient Handling

Back injuries and other musculoskeletal disorders can be caused by one bad patient lift or from the daily wear and tear of manually lifting patients. At least 56% of nurses have reported pain from musculoskeletal disorders that were exacerbated by requirements of their job. Consequences of these injuries can be devastating to nurses and their careers; musculoskeletal injuries related to patient handling are responsible for more lost work time, long-term medical care needs, and permanent disabilities than any other work-related injury. Even using proper body mechanics and the use of gait belts can result in patient handling injuries in nurses and health care workers. The ANA has established safe patient handling and mobility initiatives with the goal of complete elimination of manual patient handling.[50] See Figure 5.13[51] for an example of safe patient handling equipment.

View these videos on safe patient handling and mobility from the ANA:

Personal Protective Equipment

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requires employers to provide personal protective equipment (PPE) to their workers and ensure its proper use.[54] In health care settings, the use of PPE includes gloves, gowns, goggles, face shields, and N95 respirators according to a patient’s condition. Health care workers rely on personal protective equipment to protect themselves and their patients from being infected and infecting others. It is vital to follow agency procedures regarding PPE and transmission precautions to avoid exposure to infectious disease. See Figure 5.14[55] for an image of health care team members wearing PPE. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic created global shortages of PPE, resulting in many nurses and health care workers being exposed to the fatal disease. The ANA continues to advocate for adequate PPE for nurses in their work environments. Read more about PPE shortages in the hyperlink below.

Explore the Healthy Work Environment web page by the American Nursing Association (ANA) for additional strategies that promote safe work environments for nurses, including the Nurses' Bill of Rights and ways to put this plan into action.

In addition to promoting safety for patients and their families, it is important for nurses to be aware of safety risks in the environments and to take measures to protect themselves. Common safety risks to nurses include sharps injuries, exposure to blood-borne pathogens, lifting injuries, and lack of personal protective equipment (PPE).

Workplace Safety

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines a healthy environment as a place of physical, mental, and social well-being supporting optimal health and safety. The American Nurses Association (ANA) created the Nurses’ Bill of Rights, a document that sets forth seven basic principles concerning expectations for workplace environments. One of the ANA principles states, “Nurses have the right to a work environment that is safe for themselves and their patients.” [56] Environmental Health is also one of the ANA Standards of Professional Performance. This standard includes "creating a safe and healthy workplace and professional environment."[57]

Preventing Sharps Injuries and Blood-Borne Pathogen Exposure

Exposure to sharps and blood-borne pathogens is a critical safety issue that nurses face in the workplace.[58]Blood-borne pathogen exposure can cause life-threatening illnesses such as hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV. Regulations and laws, such as the Blood-borne Pathogen Standard from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the Needlestick Safety and Prevention Act of 2002, have been effective in significantly reducing sharps injuries and blood exposures among health care workers. Areas covered by these regulations include sharps disposal practices, evaluation and selection of safety-engineered sharps devices and personal protective equipment (PPE), training, record keeping for needlestick injuries, hepatitis B vaccination, and post exposure follow-up. Medical device manufacturers have also played an important role in reducing sharps injury risks to health care workers by developing innovative safety-engineered technology, such as needleless IV access devices.[59] While substantial progress has been made to reduce injuries, preventable sharps injuries and blood exposures continue to occur in health care settings. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), around 385,000 sharps-related injuries occur annually among health care workers in hospitals, but it has been estimated that as many as half of injuries go unreported.[60] See Figure 5.12[61] of a sharps container used to prevent sharps-related injuries.

If you do experience a sharps injury or are exposed to the blood or other body fluid of a patient, follow agency and school policy and immediately follow these steps:

- Wash needlesticks and cuts with soap and water.

- Flush splashes to the nose, mouth, or skin with water.

- Irrigate eyes with clean water, saline, or sterile irrigants.

- Report the incident to your supervisor.

- Immediately seek medical treatment.[62]

Safe Patient Handling

Back injuries and other musculoskeletal disorders can be caused by one bad patient lift or from the daily wear and tear of manually lifting patients. At least 56% of nurses have reported pain from musculoskeletal disorders that were exacerbated by requirements of their job. Consequences of these injuries can be devastating to nurses and their careers; musculoskeletal injuries related to patient handling are responsible for more lost work time, long-term medical care needs, and permanent disabilities than any other work-related injury. Even using proper body mechanics and the use of gait belts can result in patient handling injuries in nurses and health care workers. The ANA has established safe patient handling and mobility initiatives with the goal of complete elimination of manual patient handling.[63] See Figure 5.13[64] for an example of safe patient handling equipment.

View these videos on safe patient handling and mobility from the ANA:

Personal Protective Equipment

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) requires employers to provide personal protective equipment (PPE) to their workers and ensure its proper use.[67] In health care settings, the use of PPE includes gloves, gowns, goggles, face shields, and N95 respirators according to a patient’s condition. Health care workers rely on personal protective equipment to protect themselves and their patients from being infected and infecting others. It is vital to follow agency procedures regarding PPE and transmission precautions to avoid exposure to infectious disease. See Figure 5.14[68] for an image of health care team members wearing PPE. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic created global shortages of PPE, resulting in many nurses and health care workers being exposed to the fatal disease. The ANA continues to advocate for adequate PPE for nurses in their work environments. Read more about PPE shortages in the hyperlink below.

Explore the Healthy Work Environment web page by the American Nursing Association (ANA) for additional strategies that promote safe work environments for nurses, including the Nurses' Bill of Rights and ways to put this plan into action.

Patient Scenario

Mr. Olson is a 64-year-old patient admitted to the medical surgical floor with a diagnosis of pneumonia. The patient has severe macular degeneration and limited visual acuity. He is alert and oriented but notes that he has suffered a “few stumbles” at home over the last few weeks. He ambulates without assistance but relies heavily on tactile cues to help provide guidance.

Applying the Nursing Process

Assessment: The nurse notes that Mr. Olson’s macular degeneration and limited visual acuity pose a significant safety risk. He has reported “stumbling” at home and uses tactile cues to establish room boundaries.

Based on the assessment information that has been gathered, the following nursing care plan is created for Mr. Olson.

Nursing Diagnosis: Risk for Injury related to physical barrier associated with alteration in visual acuity.

Overall Goal: The patient will be free from injury or falls.

SMART Expected Outcome: Mr. Olson will be free from injury throughout his hospitalization.

Planning and Implementing Nursing Interventions:

The nurse will provide the patient with education regarding the room layout and tactile boundary cues. The nurse will keep the patient’s room free from clutter and provide appropriate lighting. The nurse will instruct the patient to utilize the call light and request assistance when ambulating throughout the room. The nurse will provide the patient with nonskid footwear to enhance safety during ambulation.

Sample Documentation

Mr. Olson is at risk for injury as a result of his decreased visual acuity and hospitalization in an unfamiliar environment. The patient has been provided education and safety equipment to decrease his risk of injury. The patient has received education regarding the room layout and has been encouraged to request assistance when ambulating about the room.

Evaluation:

During the patient’s hospitalization, Mr. Olson utilizes the recommended safety equipment and requests assistance when ambulating and no falls occurred. SMART outcome was "met."

Patient Scenario

Mr. Olson is a 64-year-old patient admitted to the medical surgical floor with a diagnosis of pneumonia. The patient has severe macular degeneration and limited visual acuity. He is alert and oriented but notes that he has suffered a “few stumbles” at home over the last few weeks. He ambulates without assistance but relies heavily on tactile cues to help provide guidance.

Applying the Nursing Process

Assessment: The nurse notes that Mr. Olson’s macular degeneration and limited visual acuity pose a significant safety risk. He has reported “stumbling” at home and uses tactile cues to establish room boundaries.

Based on the assessment information that has been gathered, the following nursing care plan is created for Mr. Olson.

Nursing Diagnosis: Risk for Injury related to physical barrier associated with alteration in visual acuity.

Overall Goal: The patient will be free from injury or falls.

SMART Expected Outcome: Mr. Olson will be free from injury throughout his hospitalization.

Planning and Implementing Nursing Interventions:

The nurse will provide the patient with education regarding the room layout and tactile boundary cues. The nurse will keep the patient’s room free from clutter and provide appropriate lighting. The nurse will instruct the patient to utilize the call light and request assistance when ambulating throughout the room. The nurse will provide the patient with nonskid footwear to enhance safety during ambulation.

Sample Documentation

Mr. Olson is at risk for injury as a result of his decreased visual acuity and hospitalization in an unfamiliar environment. The patient has been provided education and safety equipment to decrease his risk of injury. The patient has received education regarding the room layout and has been encouraged to request assistance when ambulating about the room.

Evaluation:

During the patient’s hospitalization, Mr. Olson utilizes the recommended safety equipment and requests assistance when ambulating and no falls occurred. SMART outcome was "met."

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

Assessing a patient’s risk for falls and planning interventions to prevent falls are common safety strategies completed by nurses. This section uses a patient scenario to demonstrate how to use the nursing process to assess a patient and then create a nursing care plan to prevent falls. Begin by reading the Handoff Report received from the nurse on the previous shift.

Handoff Report

Mr. Moore is a 72-year-old widower recovering in the hospital after sustaining injuries he received from a fall he sustained at home. See Figure 5.15 for an image of Mr. Moore.[69] He fractured his right hip and underwent surgical repair two days ago. He is receiving IV fluids and morphine for pain control. He has a history of hypertension and cardiovascular disease. He wears glasses and hearing aids. Per recommendations from the physical therapist, he is able to transfer with one assist with a walker, but is weak on his right side. He has an order to ambulate at least 100 feet four times daily with a wheeled walker. He is 6 feet tall and weighs 165 pounds. Prior to the fall, he lived at home alone independently, and he is looking forward to returning home.

Assessment

The nurse collects the following assessment findings:

- Vital Signs: Blood pressure 90/60, heart rate 56, respiratory rate 18, temperature 37 degrees Celsius, pulse oximetry reading 92%, current pain level 0

- Alert and oriented x 3 to person, place, and time

- Lungs clear

- Cardiovascular Assessment: Heart rate is regular, capillary refill less than 3 seconds in fingers and toes, pedal pulses 2+

- Right lower extremity strength is 1+ (weak)

- Ambulates with walker with assistance; gait is unsteady

Critical Thinking Questions

1. Describe the fall risk factors for Mr. Moore.

2. Use the Morse Fall Risk Assessment tool to assess Mr. Moore’s risk for falling.

Diagnosis

The NANDA-I nursing diagnosis is established: Risk for Falls as evidenced by lower extremity weakness and difficulty with gait.

Outcome Identification

Overall Goal: Mr. Moore will remain free from falls during his hospitalization stay.

SMART Expected Outcomes:

- Mr. Moore will not experience a fall during hospitalization.

- Mr. Moore will correctly use his assistive device (walker) every time he ambulates during hospitalization.

Planning Interventions

The following interventions are planned based on Mr. Moore’s fall risk factors.

- Remove clutter from the floor.

- Provide adequate lighting with a night-light at the bedside.

- Use half side rails to prevent falls from the bed.

- Monitor gait, balance, and fatigue with ambulation and encourage resting as needed.

- Place personal items within easy reach of the patient at the bedside.

- Provide an elevated toilet seat.

- Encourage the use of prescribed glasses and hearing aids when walking.

- Obtain orthostatic blood pressures daily and notify the provider as indicated.

- Ensure the patient wears shoes that fit properly, are fastened securely, and have no-skid soles.

- Suggest home adaptations to improve safety after discharge, such as adjusting the toilet seat height, installing grab bars in the bathroom, and using a rubber mat in the shower.

Critical Thinking Question

3. What additional interventions could be implemented for Mr. Moore to reduce his risk of falls that target his specific risk factors?

Implementation of Interventions

The following day, upon entering the room, you find Mr. Moore has climbed out of bed and is on his way to the bathroom. He states, “I need to go to the bathroom for a bowel movement and didn’t have time to ring the call light and wait.” You assist him with his walker, but he seems unsteady on his feet as he walks toward the bathroom. You’re not sure if he will make it to the toilet without falling. He says, “We need to hurry or I’m not going to make it.”

Critical Thinking Question:

4. What is the best response?

Evaluation

The nurse evaluates Mr. Moore’s progress based on the established expected outcomes:

- Mr. Moore will not experience a fall during hospitalization: Outcome Met.

- Mr. Moore will use his assistive device (walker) correctly during hospitalization: Outcome Partially Met.

Mr. Moore forgets to call for assistance and uses a walker when he needs to go to the bathroom. A “stop” sign has been placed within patient view to remind him to use the call light before getting up. In addition to hourly rounding, toileting will be performed at scheduled intervals every two hours. An icon has been posted on the doorframe to alert staff that the patient is at high risk for falls. In addition to the bed being kept low and locked, a mat will be placed next to the bed at night. If Mr. Moore continues to forget to call for assistance, a bed alarm will be placed to alert staff of movement so that quick assistance can be offered.

Professional communication with other members of the health care team is an important component of every nurse’s job. See Figure 2.8[70] for an image illustrating communication between health care team members. Common types of professional interactions include reports to health care team members, handoff reports, and transfer reports.

Reports to Health Care Team Members

Nurses routinely report information to other health care team members, as well as urgently contact health care providers to report changes in patient status.

Standardized methods of communication have been developed to ensure that information is exchanged between health care team members in a structured, concise, and accurate manner to ensure safe patient care. One common format used by health care team members to exchange patient information is ISBARR, a mnemonic for the components of Introduction, Situation, Background, Assessment, Request/Recommendations, and Repeat back.

-

- Introduction: Introduce your name, role, and the agency from which you are calling.

- Situation: Provide the patient’s name and location, why you are calling, recent vital signs, and the status of the patient.

- Background: Provide pertinent background information about the patient such as admitting medical diagnoses, code status, recent relevant lab or diagnostic results, and allergies.

- Assessment: Share abnormal assessment findings and your evaluation of the current patient situation.

- Request/Recommendations: State what you would like the provider to do, such as reassess the patient, order a lab/diagnostic test, prescribe/change medication, etc.

- Repeat back: If you are receiving new orders from a provider, repeat them to confirm accuracy. Be sure to document communication with the provider in the patient’s chart.

Read an example of an ISBARR report in the following box. A hyperlink is provided to a printable ISBARR reference card.

Sample ISBARR Report From a Nurse to a Health Care Provider

I: “Hello Dr. Smith, this is Jane White, RN from the Med Surg unit.”

S: “I am calling to tell you about Ms. White in Room 210, who is experiencing an increase in pain, as well as redness at her incision site. Her recent vital signs were BP 160/95, heart rate 90, respiratory rate 22, O2 sat 96%, and temperature 38 degrees Celsius. She is stable but her pain is worsening.”

B: “Ms. White is a 65-year-old female, admitted yesterday post hip surgical replacement. She has been rating her pain at 3 or 4 out of 10 since surgery with her scheduled medication, but now she is rating the pain as a 7, with no relief from her scheduled medication of Vicodin 5/325 mg administered an hour ago. She is scheduled for physical therapy later this morning and is stating she won’t be able to participate because of the pain this morning.”

A: “I just assessed the surgical site and her dressing was clean, dry, and intact, but there is 4 cm redness surrounding the incision, and it is warm and tender to the touch. There is moderate serosanguinous drainage. Otherwise, her lungs are clear and her heart rate is regular.”

R: “I am calling to request an order for a CBC and increased dose of pain medication.”

R: “I am repeating back the order to confirm that you are ordering a STAT CBC and an increase of her Vicodin to 10/325 mg.”

View or print an ISBARR reference card

.

Handoff Reports

Handoff reports are defined by The Joint Commission as “a transfer and acceptance of patient care responsibility achieved through effective communication. It is a real-time process of passing patient specific information from one caregiver to another, or from one team of caregivers to another, for the purpose of ensuring the continuity and safety of the patient’s care.”[71] In 2017, The Joint Commission issued a sentinel alert about inadequate handoff communication that has resulted in patient harm such as wrong-site surgeries, delays in treatment, falls, and medication errors. Strategies for improving handoff communication have been implemented at agencies across the country.

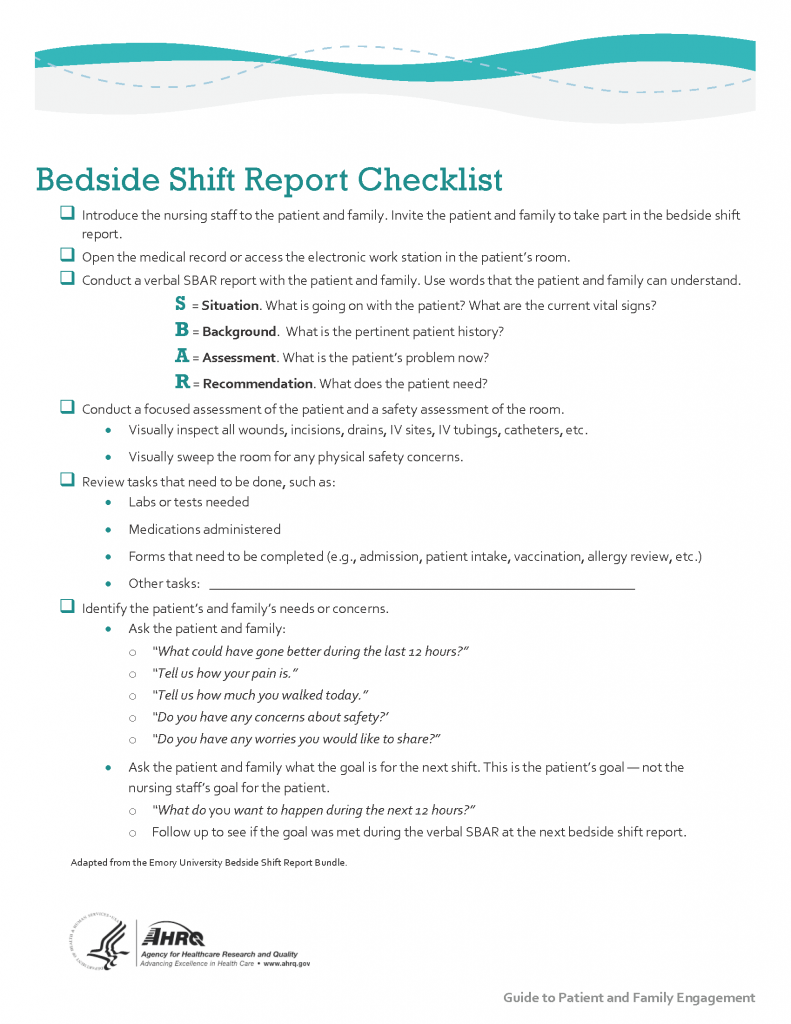

Although many types of nursing shift-to-shift handoff reports have been used over the years, evidence strongly supports that bedside handoff reports increase patient safety, as well as patient and nurse satisfaction, by effectively communicating current, accurate patient information in real time.[72] See Figure 2.9[73] for an image illustrating two nurses participating in a handoff report. Bedside reports typically occur in hospitals and include the patient, along with the off-going and the oncoming nurses in a face-to-face handoff report conducted at the patient's bedside. HIPAA rules must be kept in mind if visitors are present or the room is not a private room. Family members may be included with the patient’s permission. See a sample checklist for a bedside handoff report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality in Figure 2.10.[74] Although a bedside handoff report is similar to an ISBARR report, it contains additional information to ensure continuity of care across nursing shifts. For example, the “assessment” portion of the bedside handoff report includes detailed pertinent data the oncoming nurse needs to know, such as current head-to-toe assessment findings to establish a baseline; information about equipment such as IVs, catheters, and drainage tubes; and recent changes in medications, lab results, diagnostic tests, and treatments.

![]"618721604-huge" by Rido is used under license from Shutterstock.com. Image showing two nurses discussing a chart both are holding](https://nicoletcollege.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/55/2022/04/618721604-huge-scaled-1.jpg)

View Sample Information to Include in a Shift Report.

View a video on creating shift reports.[75]

Transfer Reports

Transfer reports are provided by nurses when transferring a patient to another unit or to another agency. Transfer reports contain similar information as bedside handoff reports, but are even more detailed when the patient is being transferred to another agency. Checklists are often provided by agencies to ensure accurate, complete information is shared.

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

Assessing a patient’s risk for falls and planning interventions to prevent falls are common safety strategies completed by nurses. This section uses a patient scenario to demonstrate how to use the nursing process to assess a patient and then create a nursing care plan to prevent falls. Begin by reading the Handoff Report received from the nurse on the previous shift.

Handoff Report

Mr. Moore is a 72-year-old widower recovering in the hospital after sustaining injuries he received from a fall he sustained at home. See Figure 5.15 for an image of Mr. Moore.[76] He fractured his right hip and underwent surgical repair two days ago. He is receiving IV fluids and morphine for pain control. He has a history of hypertension and cardiovascular disease. He wears glasses and hearing aids. Per recommendations from the physical therapist, he is able to transfer with one assist with a walker, but is weak on his right side. He has an order to ambulate at least 100 feet four times daily with a wheeled walker. He is 6 feet tall and weighs 165 pounds. Prior to the fall, he lived at home alone independently, and he is looking forward to returning home.

Assessment

The nurse collects the following assessment findings:

- Vital Signs: Blood pressure 90/60, heart rate 56, respiratory rate 18, temperature 37 degrees Celsius, pulse oximetry reading 92%, current pain level 0

- Alert and oriented x 3 to person, place, and time

- Lungs clear

- Cardiovascular Assessment: Heart rate is regular, capillary refill less than 3 seconds in fingers and toes, pedal pulses 2+

- Right lower extremity strength is 1+ (weak)

- Ambulates with walker with assistance; gait is unsteady

Critical Thinking Questions

1. Describe the fall risk factors for Mr. Moore.

2. Use the Morse Fall Risk Assessment tool to assess Mr. Moore’s risk for falling.

Diagnosis

The NANDA-I nursing diagnosis is established: Risk for Falls as evidenced by lower extremity weakness and difficulty with gait.

Outcome Identification

Overall Goal: Mr. Moore will remain free from falls during his hospitalization stay.

SMART Expected Outcomes:

- Mr. Moore will not experience a fall during hospitalization.

- Mr. Moore will correctly use his assistive device (walker) every time he ambulates during hospitalization.

Planning Interventions

The following interventions are planned based on Mr. Moore’s fall risk factors.

- Remove clutter from the floor.

- Provide adequate lighting with a night-light at the bedside.

- Use half side rails to prevent falls from the bed.

- Monitor gait, balance, and fatigue with ambulation and encourage resting as needed.

- Place personal items within easy reach of the patient at the bedside.

- Provide an elevated toilet seat.

- Encourage the use of prescribed glasses and hearing aids when walking.

- Obtain orthostatic blood pressures daily and notify the provider as indicated.

- Ensure the patient wears shoes that fit properly, are fastened securely, and have no-skid soles.

- Suggest home adaptations to improve safety after discharge, such as adjusting the toilet seat height, installing grab bars in the bathroom, and using a rubber mat in the shower.

Critical Thinking Question

3. What additional interventions could be implemented for Mr. Moore to reduce his risk of falls that target his specific risk factors?

Implementation of Interventions

The following day, upon entering the room, you find Mr. Moore has climbed out of bed and is on his way to the bathroom. He states, “I need to go to the bathroom for a bowel movement and didn’t have time to ring the call light and wait.” You assist him with his walker, but he seems unsteady on his feet as he walks toward the bathroom. You’re not sure if he will make it to the toilet without falling. He says, “We need to hurry or I’m not going to make it.”

Critical Thinking Question:

4. What is the best response?

Evaluation

The nurse evaluates Mr. Moore’s progress based on the established expected outcomes:

- Mr. Moore will not experience a fall during hospitalization: Outcome Met.

- Mr. Moore will use his assistive device (walker) correctly during hospitalization: Outcome Partially Met.

Mr. Moore forgets to call for assistance and uses a walker when he needs to go to the bathroom. A “stop” sign has been placed within patient view to remind him to use the call light before getting up. In addition to hourly rounding, toileting will be performed at scheduled intervals every two hours. An icon has been posted on the doorframe to alert staff that the patient is at high risk for falls. In addition to the bed being kept low and locked, a mat will be placed next to the bed at night. If Mr. Moore continues to forget to call for assistance, a bed alarm will be placed to alert staff of movement so that quick assistance can be offered.

Functional Ability Case Study by Susan Jepsen for Lansing Community College are licensed under CC BY 4.0