Diverse Patients

3.4 Cultural Competence

The freedom to express one’s cultural beliefs is a fundamental right of all people. Nurses realize that people speak, behave, and act in many different ways due to the influential role that culture plays in their lives and their view of the world. Cultural competence is a lifelong process of applying evidence-based nursing in agreement with the cultural values, beliefs, worldview, and practices of patients to produce improved patient outcomes.[1],[2],[3]

Culturally-competent care requires nurses to combine their knowledge and skills with awareness, curiosity, and sensitivity about their patients’ cultural beliefs. It takes motivation, time, and practice to develop cultural competence, and it will evolve throughout your nursing career. Culturally competent nurses have the power to improve the quality of care leading to better health outcomes for culturally diverse patients. Nurses who accept and uphold the cultural values and beliefs of their patients are more likely to develop supportive and trusting relationships with their patients. In turn, this opens the way for optimal disease and injury prevention and leads towards positive health outcomes for all patients .

The roots of providing culturally-competent care are based on the original transcultural nursing theory developed by Dr. Madeleine Leininger. Transcultural nursing incorporates cultural beliefs and practices of individuals to help them maintain and regain health or to face death in a meaningful way.[4] See Figure 3.4[5] for an image of Dr. Leininger. Read more about transcultural nursing theory in the following box.

Madeleine Leininger and the Transcultural Nursing Theory[6]

Dr. Madeleine Leininger (1925-2012) founded the transcultural nursing theory. She was the first professional nurse to obtain a PhD in anthropology. She combined the “culture” concept from anthropology with the “care” concept from nursing and reformulated these concepts into “culture care.”

In the mid-1950s, no cultural knowledge base existed to guide nursing decisions or understand cultural behaviors as a way of providing therapeutic care. Leininger wrote the first books in the field and coined the term “culturally congruent care.” She developed and taught the first transcultural nursing course in 1966, and master’s and doctoral programs in transcultural nursing were launched shortly after. Dr. Leininger was honored as a Living Legend of the American Academy of Nursing in 1998.

Nurses have an ethical and moral obligation to provide culturally competent care to the patients they serve.[7] The “Respectful and Equitable Practice” Standard of Professional Performance set by the American Nurses Association (ANA) states that nurses must practice with cultural humility and inclusiveness. The ANA Code of Ethics also states that the nurse should collaborate with other health professionals, as well as the public, to protect human rights, fight discriminatory practices, and reduce disparities.[8] Additionally, the ANA Code of Ethics also states that nurses “are expected to be aware of their own cultural identifications in order to control their personal biases that may interfere with the therapeutic relationship. Self-awareness involves not only examining one’s culture but also examining perceptions and assumptions about the patient’s culture…nurses should possess knowledge and understanding how oppression, racism, discrimination, and stereotyping affect them personally and in their work.”[9]

Developing cultural competence begins in nursing school.[10],[11] Culture is an integral part of life, but its impact is often implicit. It is easy to assume that others share the same cultural values that you do, but each individual has their own beliefs, values, and preferences. Begin the examination of your own cultural beliefs and feelings by answering the questions below.[12]

Reflect on the following questions carefully and contemplate your responses as you begin your journey of providing culturally responsive care as a nurse. (Questions are adapted from the Anti Defamation League’s “Imagine a World Without Hate” Personal Self-Assessment Anti-Bias Behavior).[13]

- Who are you? With what cultural group or subgroups do you identify?

- When you meet someone from another culture/country/place, do you try to learn more about them?

- Do you notice instances of bias, prejudice, discrimination, and stereotyping against people of other groups or cultures in your environment (home, school, work, TV programs or movies, restaurants, places where you shop)?

- Have you reflected on your own upbringing and childhood to better understand your own implicit biases and the ways you have internalized messages you received?

- Do you ever consider your use of language to avoid terms or phrases that may be degrading or hurtful to other groups?

- When other people use biased language and behavior, do you feel comfortable speaking up and asking them to refrain?

- How ready are you to give equal attention, care, and support to people regardless of their culture, socioeconomic class, religion, gender expression, sexual orientation, or other “difference”?

The Process of Developing Cultural Competence

Dr. Josephine Campinha-Bacote is an influential nursing theorist and researcher who developed a model of cultural competence. The model asserts there are specific characteristics that a nurse becoming culturally competent possesses, including cultural awareness, cultural knowledge, cultural skill, and cultural encounters.[14]

Cultural awareness is a deliberate, cognitive process in which health care providers become appreciative and sensitive to the values, beliefs, attitudes, practices, and problem-solving strategies of a patient’s culture. To become culturally aware, the nurse must undergo reflective exploration of personal cultural values while also becoming conscious of the cultural practices of others. In addition to reflecting on one’s own cultural values, the culturally competent nurse seeks to reverse harmful prejudices, ethnocentric views, and attitudes they have. Cultural awareness goes beyond a simple awareness of the existence of other cultures and involves an interest, curiosity, and appreciation of other cultures. Although cultural diversity training is typically a requirement for health care professionals, cultural desire refers to the intrinsic motivation and commitment on the part of a nurse to develop cultural awareness and cultural competency.[15]

Acquiring cultural knowledge is another important step towards becoming a culturally competent nurse. Cultural knowledge refers to seeking information about cultural health beliefs and values to understand patients’ world views. To acquire cultural knowledge, the nurse actively seeks information about other cultures, including common practices, beliefs, values, and customs, particularly for those cultures that are prevalent within the communities they serve.[16] Cultural knowledge also includes understanding the historical backgrounds of culturally diverse groups in society, as well as physiological variations and the incidence of certain health conditions in culturally diverse groups. Cultural knowledge is best obtained through cultural encounters with patients from diverse backgrounds to learn about individual variations that occur within cultural groups and to prevent stereotyping.

While obtaining cultural knowledge, it is important to demonstrate cultural sensitivity. Cultural sensitivity means being tolerant and accepting of cultural practices and beliefs of people. Cultural sensitivity is demonstrated when the nurse conveys nonjudgmental interest and respect through words and action and an understanding that some health care treatments may conflict with a person’s cultural beliefs.[17] Cultural sensitivity also implies a consciousness of the damaging effects of stereotyping, prejudice, or biases on patients and their well-being. Nurses who fail to act with cultural sensitivity may be viewed as uncaring or inconsiderate, causing a breakdown in trust for the patient and their family members. When a patient experiences nursing care that contradicts with their cultural beliefs, they may experience moral or ethical conflict, nonadherence, or emotional distress.

Cultural desire, awareness, sensitivity, and knowledge are the building blocks for developing cultural skill. Cultural skill is reflected by the nurse’s ability to gather and synthesize relevant cultural information about their patients while planning care and using culturally sensitive communication skills. Nurses with cultural skill provide care consistent with their patients’ cultural needs and deliberately take steps to secure a safe health care environment that is free of discrimination or intolerance. For example, a culturally skilled nurse will make space and seating available within a patient’s hospital room for accompanying family members when this support is valued by the patient.[18]

Cultural encounters is a process where the nurse directly engages in face-to-face cultural interactions and other types of encounters with clients from culturally diverse backgrounds in order to modify existing beliefs about a cultural group and to prevent possible stereotyping.

By developing the characteristics of cultural awareness, cultural knowledge, cultural skill, and cultural encounters, a nurse develops cultural competence.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, October 21). Cultural competence in health and human services. https://npin.cdc.gov/pages/cultural-competence ↵

- Curtis, E., Jones, R., Tipene-Leach, D., Walker, C., Loring, B., Paine, S.-J., & Reid, P. (2019). Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: A literature review and recommended definition. International Journal for Equity in Health, 18, 174. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-1082-3 ↵

- Young, S., & Guo, K. (2016). Cultural diversity training: The necessity for cultural competence for healthcare providers and in nursing practice. The Health Care Manager, 35(2), 94-102. https://doi.org/10.1097/hcm.0000000000000100 ↵

- Murphy, S. C. (2006). Mapping the literature of transcultural nursing. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 94(2 Suppl), e143–e151. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1463039/ ↵

- “Leininger.jpg” by Juda712 is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Murphy, S. C. (2006). Mapping the literature of transcultural nursing. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 94(2 Suppl), e143–e151. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1463039/ ↵

- Young, S., & Guo, K. (2016). Cultural diversity training: The necessity for cultural competence for healthcare providers and in nursing practice. The Health Care Manager, 35(2), 94-102. https://doi.org/10.1097/hcm.0000000000000100 ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/ ↵

- Gillson, S., & Cherian, N. (2019). The importance of teaching cultural diversity in baccalaureate nursing education. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 26(3), 85–88. ↵

- Gavin-Knecht, J., Fontana, J. S., Fischer, B., Spitz, K. R., & Tetreault, J. N. (2018). An investigation of the development of cultural competence in baccalaureate nursing students: A mixed methods study. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 26(3), 89-95. ↵

- Zeran, V. (2016). Cultural competency and safety in nursing education: A case study. Northern Review, 43, 105–115. https://thenorthernreview.ca/index.php/nr/article/view/591 ↵

- Anti-Defamation League. (2013). Imagine a world without hate: Anti-Defamation League 2012 Annual Report. https://www.adl.org/media/4528/download. ↵

- Transcultural C.A.R.E. Associates. (2020). The Process of Cultural Competemility. http://transculturalcare.net/the-process-of-cultural-competence-in-the-delivery-of-healthcare-services/ ↵

- Anti-Defamation League. (2013). Imagine a world without hate: Anti-Defamation League 2012 Annual Report. https://www.adl.org/media/4528/download. ↵

- Gillson, S., & Cherian, N. (2019). The importance of teaching cultural diversity in baccalaureate nursing education. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 26(3), 85–88. ↵

- Curtis, E., Jones, R., Tipene-Leach, D., Walker, C., Loring, B., Paine, S.-J., & Reid, P. (2019). Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: A literature review and recommended definition. International Journal for Equity in Health, 18, 174. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-1082-3 ↵

- Brooks, L., Manias, E., & Bloomer, M. (2019). Culturally sensitive communication in healthcare: A concept analysis. Collegian, 26(3), 383-391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2018.09.007 ↵

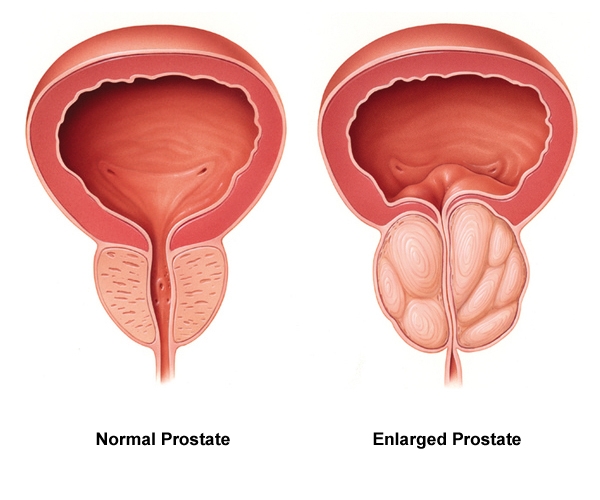

Urinary retention is a condition when the patient cannot empty all of the urine from their bladder. Urinary retention can be acute (i.e., the sudden inability to urinate after receiving anesthesia during surgery) or chronic (i.e., a gradual inability to completely empty the bladder due to enlargement of the prostate gland in males). Urinary retention is caused by a blockage that partially or fully prevents the flow of urine or the bladder not being able to create a strong enough force to expel all the urine. In addition to causing discomfort, urinary retention increases the patient’s risk for developing a urinary tract infection (UTI). See Figure 16.5[1] for an image of an enlarged prostate gland blocking the flow of urine from the bladder into the urethra.

Symptoms of urinary retention can range from none to severe abdominal pain.[2] Health care providers use a patient’s medical history, physical exam finding, and diagnostic tests to find the cause of urinary retention. Nurses typically receive orders to measure post-void residual amounts when urinary retention is suspected. Post-void residual measurements are taken after a patient has voided by using a bladder scanner or inserting a straight urinary catheter to determine how much urine is left in the bladder. See the following box regarding how to perform a bladder scan at the bedside. Read about other diagnostic tests related to urinary retention, such as urodynamic testing and cystoscopy, under the “Applying the Nursing Process” section of this chapter.[3]

Performing a Bladder Scan

A bladder scanner is a portable, noninvasive medical device that uses sound waves to calculate the amount of urine in a patient’s bladder. Nurses use bladder scanners at the bedside to determine post-void residual urine amounts in patients to avoid the need to perform an invasive urinary catheterization. Typically the use of a bladder scan does not require a physician order, but be sure to check agency policy.

After the patient voids and is lying in a supine position, turn on the device and indicate if the patient is male or female. (If the female has had a hysterectomy, then “male” is selected.) Apply warmed gel to the transducer head, and then place it approximately one inch above the symphysis pubis with the probe directed towards the bladder. Press the "scan" button, making sure to hold the scanner steady until you hear a beep. The bladder scanner will display the volume measured using a display with crosshairs. If the crosshairs are not centered on the urine displayed, adjust the probe and rescan until it is properly centered. If the post-void residual is greater than 300 mL, the provider should be notified and typically an order will be received for a straight urinary catheterization. Whenever possible, indwelling urinary catheterization (also referred to as a “Foley”) placement is avoided to reduce the patient’s risk of developing a catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI).[4]

View this following YouTube video to see a bladder scanner in use[5]: How to Use BladderScan Prime Plus™ by Diane Newman

Interventions

Treatment for urinary retention depends on the cause. It may include urinary catheterization to drain the bladder, bladder training therapy, medications, or surgery.[6] Read more about bladder training therapy under the “Urinary Incontinence” section. Alpha blockers, such as tamsulosin (Flomax), are used to treat urinary retention caused by an enlarged prostate. A surgery called transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) may be performed to treat urinary retention caused by an enlarged prostate that is not responsive to medication.

Read more about alpha-blocker medication (i.e., tamsulosin) in the “Autonomic Nervous System” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

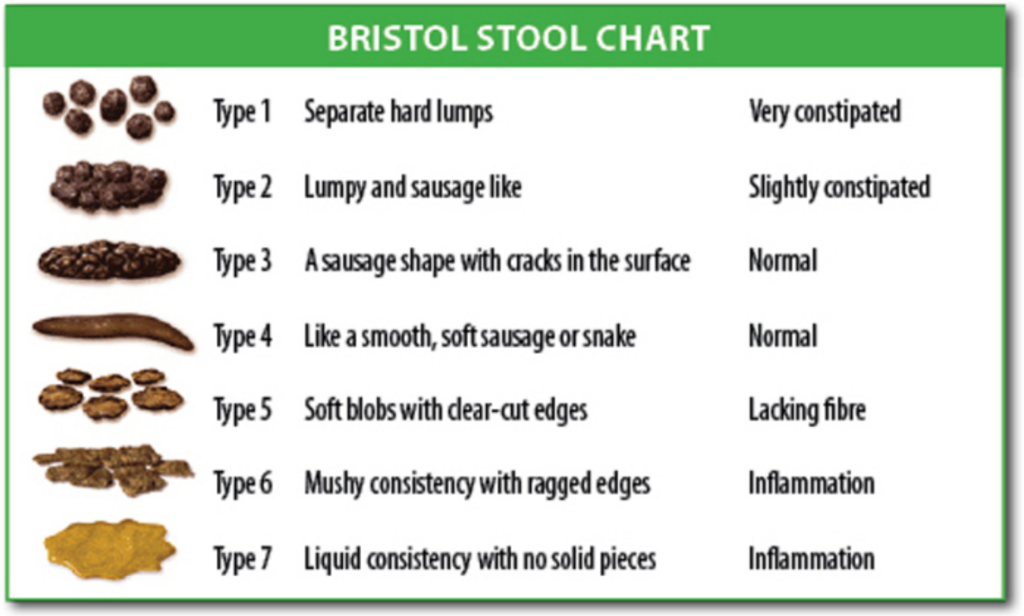

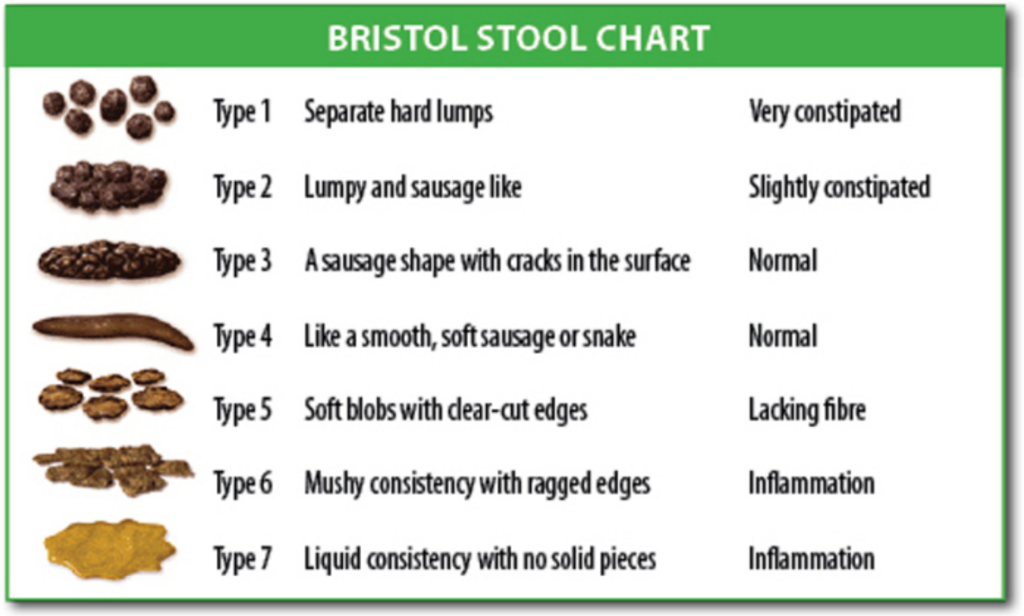

Constipation is defined by NANDA-I as, “A decrease in normal frequency of defecation accompanied by difficult or incomplete passage of stool and/or passage of excessively hard, dry stool.”[7] Typically a patient is diagnosed with constipation if they have less than three bowel movements per week. Constipation can be caused by slowed peristalsis due to decreased activity, dehydration, lack of fiber, medications such as opioids, depression, or surgical procedures in the abdominal area. As the stool moves slowly through the large intestine, additional water is reabsorbed, resulting in the stool becoming hard, dry, and difficult to move through the lower intestines. See Figure 16.6[8] for the Bristol Stool Chart used to assess the characteristics of stools ranging from constipation to diarrhea.

The patient may experience associated symptoms such as rectal pressure, abdominal cramps, bloating, distension, and straining. Fecal impaction can occur when stool accumulates in the rectum, usually due to the patient not feeling the presence of stool or not using the toilet when the urge is felt. Large balls of hard stool need to be digitally removed or treated with mineral oil enemas.

Interventions

The goal of interventions implemented to treat constipation is to establish what is considered a normal bowel pattern for each patient and to set an expected outcome of a bowel movement at least every 72 hours regardless of intake. Treatment typically includes a prescribed daily bowel regimen, such as oral stool softeners (e.g., docusate) and a mild stimulant laxative (e.g., sennosides). Stronger laxatives (e.g., Milk of Magnesia or bisacodyl), rectal suppositories, or enemas are implemented when oral medications are not effective.

Patients should be educated about the importance of increased fluids, increased dietary fiber, and increased activity to prevent constipation. Some food sources, such as prune juice, prunes, and apricots, are helpful in preventing constipation. Over-the-counter medication, such as methylcellulose or psyllium, can be used to increase dietary fiber. When administering these medications, mix in a full 8-ounce glass of water to avoid the development of an intestinal obstruction.

Read more about laxatives used to treat constipation in the “Gastrointestinal” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

Intestinal Obstruction or Paralytic Ileus

Intestinal obstruction is a partial or complete blockage of the intestines so that contents of the intestine cannot pass through it. It can be caused by paralytic ileus, a condition where peristalsis is not propelling the contents through the intestines, or by a mechanical cause, such as fecal impaction. Patients who have undergone abdominal surgery or received general anesthesia are at increased risk for paralytic ileus. Other risk factors include the chronic use of opioids, electrolyte imbalances, bacterial or viral infections of the intestines, decreased blood flow to the intestines, or kidney or liver disease. If an obstruction blocks the blood supply to the intestine, it can cause infection and tissue death (gangrene).[9]

Symptoms of an intestinal obstruction or paralytic ileus include abdominal distention or a feeling of fullness, abdominal pain or cramping, inability to pass gas, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea. Because of the common occurrence of paralytic ileus in postoperative patients, nurses routinely monitor for these symptoms, and diet orders are not upgraded until the patient is able to pass gas.

Treatment may include insertion of an NG tube attached to suction to help relieve abdominal distention and vomiting until peristalsis returns. Obstructions may require surgery if the tube does not relieve the symptoms or if there are signs of tissue death.[10]

Diarrhea is defined as having more than three unformed stools in 24 hours. It can cause dehydration, skin breakdown, and electrolyte imbalances. Diarrhea is caused by increased peristalsis causing the stool to move too quickly through the large intestines so that water is not effectively reabsorbed, resulting in loose, watery stools.

Many conditions can cause diarrhea, such as infectious processes (bacteria, viruses, and protozoa), food poisoning, medications (such as antibiotics and laxatives), food intolerances, allergies, anxiety, and medical conditions like irritable bowel disease and Crohn's disease, or dumping syndrome for patients receiving tube feeding. Antibiotic therapy also places patients at risk of developing Clostridium difficile (C-diff) due to the elimination of normal flora in the gastrointestinal tract. Patients with C-diff have very watery, foul-smelling stools, and transmission-based precautions are implemented to prevent the spread of infection.

Read more about C-diff and transmission-based precautions in the “Infection” chapter in this text.

Interventions

Treatment of diarrhea includes promoting hydration with water or other fluids (e.g., sports drinks) that improve electrolyte status. Intravenous fluids may be required if the patient becomes dehydrated. Medications such as loperamide, psyllium, and anticholinergic agents may be prescribed to treat diarrhea causing dehydration. In some cases, rectal tubes may be prescribed to collect watery stool. However, strict monitoring is required due to possible damage to the rectal mucosa.

Read about medications used to treat diarrhea in the “Gastrointestinal” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

Constipation is defined by NANDA-I as, “A decrease in normal frequency of defecation accompanied by difficult or incomplete passage of stool and/or passage of excessively hard, dry stool.”[11] Typically a patient is diagnosed with constipation if they have less than three bowel movements per week. Constipation can be caused by slowed peristalsis due to decreased activity, dehydration, lack of fiber, medications such as opioids, depression, or surgical procedures in the abdominal area. As the stool moves slowly through the large intestine, additional water is reabsorbed, resulting in the stool becoming hard, dry, and difficult to move through the lower intestines. See Figure 16.6[12] for the Bristol Stool Chart used to assess the characteristics of stools ranging from constipation to diarrhea.

The patient may experience associated symptoms such as rectal pressure, abdominal cramps, bloating, distension, and straining. Fecal impaction can occur when stool accumulates in the rectum, usually due to the patient not feeling the presence of stool or not using the toilet when the urge is felt. Large balls of hard stool need to be digitally removed or treated with mineral oil enemas.

Interventions

The goal of interventions implemented to treat constipation is to establish what is considered a normal bowel pattern for each patient and to set an expected outcome of a bowel movement at least every 72 hours regardless of intake. Treatment typically includes a prescribed daily bowel regimen, such as oral stool softeners (e.g., docusate) and a mild stimulant laxative (e.g., sennosides). Stronger laxatives (e.g., Milk of Magnesia or bisacodyl), rectal suppositories, or enemas are implemented when oral medications are not effective.

Patients should be educated about the importance of increased fluids, increased dietary fiber, and increased activity to prevent constipation. Some food sources, such as prune juice, prunes, and apricots, are helpful in preventing constipation. Over-the-counter medication, such as methylcellulose or psyllium, can be used to increase dietary fiber. When administering these medications, mix in a full 8-ounce glass of water to avoid the development of an intestinal obstruction.

Read more about laxatives used to treat constipation in the “Gastrointestinal” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

Intestinal Obstruction or Paralytic Ileus

Intestinal obstruction is a partial or complete blockage of the intestines so that contents of the intestine cannot pass through it. It can be caused by paralytic ileus, a condition where peristalsis is not propelling the contents through the intestines, or by a mechanical cause, such as fecal impaction. Patients who have undergone abdominal surgery or received general anesthesia are at increased risk for paralytic ileus. Other risk factors include the chronic use of opioids, electrolyte imbalances, bacterial or viral infections of the intestines, decreased blood flow to the intestines, or kidney or liver disease. If an obstruction blocks the blood supply to the intestine, it can cause infection and tissue death (gangrene).[13]

Symptoms of an intestinal obstruction or paralytic ileus include abdominal distention or a feeling of fullness, abdominal pain or cramping, inability to pass gas, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea. Because of the common occurrence of paralytic ileus in postoperative patients, nurses routinely monitor for these symptoms, and diet orders are not upgraded until the patient is able to pass gas.

Treatment may include insertion of an NG tube attached to suction to help relieve abdominal distention and vomiting until peristalsis returns. Obstructions may require surgery if the tube does not relieve the symptoms or if there are signs of tissue death.[14]

Bowel incontinence is the accidental loss of bowel control causing the unexpected passage of stool. Incontinence can range from leaking a small amount of stool or gas to not being able to control bowel movements. The rectum, anus, pelvic muscles, and nervous system must work together to control bowel movements. A patient must also be able to recognize and respond to the urge to have a bowel movement. If there is a problem with any of these factors, bowel incontinence can occur.[15]

Causes of bowel incontinence include the following:

- Ongoing (chronic) constipation, causing the anus muscles and intestines to stretch and weaken, leading to diarrhea and stool leakage

- Fecal impaction with a lump of hard stool that partly blocks the large intestine

- Long-term laxative use

- Colectomy or bowel surgery

- Lack of sensation of the need to have a bowel movement

- Gynecological, prostate, or rectal surgery

- Injury to the anal muscles in women due to childbirth

- Nerve or muscle damage from injury, a tumor, or radiation

- Severe diarrhea that causes leakage

- Severe hemorrhoids or rectal prolapse

- Stress of being in an unfamiliar environment

- Emotional or mental health issues[16]

Interventions

Many people feel embarrassed about bowel incontinence and do not share this information with their health care provider. It is essential for nurses to communicate therapeutically with patients experiencing bowel incontinence and let them know it can often be treated with simple changes such as diet changes, bowel retraining, pelvic floor exercises, or surgery.[17]

Ask the patient to track the foods eaten to determine if certain types of foods cause problems. Foods that may lead to incontinence in some people include the following:

- Alcohol

- Caffeine

- Dairy products (due to lactose intolerance)

- Fatty, fried, or greasy foods

- Spicy foods

- Cured or smoked meats

- Sweeteners such as fructose, mannitol, sorbitol, and xylitol[18]

It is often helpful to add fiber to the diet to add bulk and thicken loose stool. To increase fiber, encourage the patient to eat whole grains with a goal of 30 grams of fiber a day. Other products, such as psyllium, can be used to add bulk to stools.[19]

Bowel retraining involves teaching the body to have a bowel movement at a certain time of the day. This also includes encouraging the patient to go to the bathroom when feeling the urge to do so and not ignoring it. For some people, it is helpful to schedule this consistent time in the morning when the natural urge occurs after drinking warm fluids or eating breakfast. For other people, especially those with a neurological cause, a laxative may be scheduled every three days to stimulate the urge to have a bowel movement.[20]

Patients can be educated about pelvic floor exercises to regain control of their anal sphincter muscle.[21]Read more about pelvic floor exercises under the “Urinary Incontinence” section.

Some patients can't tell when it's time to have a bowel movement or they can't move well enough to get to the bathroom safely on their own. These patients require special care in long-term care settings. To promote effective bowel movements, assist them to the toilet after meals and when they feel the urge. Also, make sure the bathroom is comfortable and private.[22]

If these simple treatments do not work, surgery may be needed to correct the problem. There are several types of procedures that a surgeon selects based on the cause of the bowel incontinence and the person's general health.[23]

Encourage patients with bowel incontinence to use special pads or undergarments to help them feel protected from accidents when they leave home. These products are available in pharmacies and in many other stores.