Diverse Patients

3.2 Diverse Patients Basic Concepts

Let’s begin the journey of developing cultural competency by exploring basic concepts related to culture.

Culture and Subculture

Culture is a set of beliefs, attitudes, and practices shared by a group of people or community that is accepted, followed, and passed down to other members of the group. The word “culture” may at times be interchanged with terms such as ethnicity, nationality, or race. See Figure 3.1[1] for an illustration depicting culture by various nationalities. Cultural beliefs and practices bind group or community members together and help form a cohesive identity.[2],[3] Culture has an enduring influence on a person’s view of the world, expressed through language and communication patterns, family connections and kinship, religion, cuisine, dress, and other customs and rituals.[4] Culture is not static but is dynamic and ever-changing; it changes as members come into contact with beliefs from other cultures. For example, sushi is a traditional Asian dish that has become popular in America in recent years.

Nurses and other health care team members are impacted by their own personal cultural beliefs. For example, a commonly held belief in American health care is the importance of timeliness; medications are administered at specifically scheduled times, and appearing for appointments on time is considered crucial.

Most cultural beliefs are a combination of beliefs, values, and habits that have been passed down through family members and authority figures. The first step in developing cultural competence is to become aware of your own cultural beliefs, attitudes, and practices.

Nurses should also be aware of subcultures. A subculture is a smaller group of people within a culture, often based on a person’s occupation, hobbies, interests, or place of origin. People belonging to a subculture may identify with some, but not all, aspects of their larger “parent” culture. Members of the subculture share beliefs and commonalities that set them apart and do not always conform with those of the larger culture. See Table 3.2a for examples of subcultures.

Table 3.2a Examples of Subcultures

| Age/Generation | Baby Boomers, Millennials, Gen Z |

|---|---|

| Occupation | Truck Driver, Computer Scientist, Nurse |

| Hobbies/Interests | Birdwatchers, Gamers, Foodies, Skateboarders |

| Religion | Hinduism, Baptist, Islam |

| Gender | Male, Female, Nonbinary, Two-Spirit |

| Geography | Rural, Urban, Southern, Midwestern |

Culture is much more than a person’s nationality or ethnicity. Culture can be expressed in a multitude of ways, including the following:

- Language(s) spoken

- Religion and spiritual beliefs

- Gender identity

- Socioeconomic status

- Age

- Sexual orientation

- Geography

- Educational background

- Life experiences

- Living situation

- Employment status

- Immigration status

- Ability/Disability

People typically belong to more than one culture simultaneously. These cultures overlap, intersect, and are woven together to create a person’s cultural identity. In other words, the many ways in which a person expresses their cultural identity are not separated, but are closely intertwined, referred to as intersectionality.

Assimilation

Assimilation is the process of adopting or conforming to the practices, habits, and norms of a cultural group. As a result, the person gradually takes on a new cultural identity and may lose their original identity in the process.[5] An example of assimilation is a newly graduated nurse, who after several months of orientation on the hospital unit, offers assistance to a colleague who is busy. The new nurse has developed self-confidence in the role and has developed an understanding that helping others is a norm for the nurses on that unit.

Assimilation is not always voluntary, however, and may become a source of distress. There are historic examples of involuntary assimilation in many countries. For example, in the past, authorities in the United States and Canadian governments required indigenous children to attend boarding schools, separated them from their families, and punished them for speaking their native language.[6],[7]

Cultural Values and Beliefs

Culture provides an important source of values and comfort for patients, families, and communities. Think of culture as a thread that is woven through a person’s world and impacts one’s choices, perspectives, and way of life. It plays a role in all of a person’s life events and threads its way through the development of one’s self-concept, sexuality, and spirituality. It affects lifelong nutritional habits, as well as coping strategies with death and dying.

Culture influences how a patient interprets “good” health, as well as their perspectives on illness and the causes of illness. The manner in which pain is expressed is also shaped by a person’s culture. See Table 3.2b for additional examples of how a person’s culture impacts common values and beliefs regarding family patterns, communication patterns, space orientation, time orientation, and nutritional patterns. As you read Table 3.2b, take a moment to reflect on your own cultural background and your personally held beliefs for each of these concepts.

Table 3.2b Cultural Concepts

| Cultural Concepts | Examples of Culturally Influenced Values and Beliefs |

|---|---|

| Family Patterns | Family size

Views on contraception Roles of family members Naming customs Value placed on elders and children Discipline/upbringing of children Rites of passage End-of-life care |

| Communication Patterns | Eye contact

Touch Use of silence or humor Intonation, vocabulary, grammatical structure Topics considered personal (i.e., difficult to discuss) Greeting customs (handshakes, hugs) |

| Space Orientation | Personal distance and intimate space |

| Time Orientation | Focus on the past, present, or future

Importance of following a routine or schedule Arrival on time for appointments |

| Nutritional Patterns | Common meal choices

Foods to avoid Foods to heal or treat disease Religious practices (e.g., fasting, dietary restrictions) Foods to celebrate life events and holidays |

A person’s culture can also affect encounters with health care providers in other ways, such as the following:

- Level of family involvement in care

- Timing for seeking care

- Acceptance of treatment (as preventative measure or for an actual health problem)

- The accepted decision-maker (i.e., the patient or other family members)

- Use of home or folk remedies

- Seeking advice or treatment from nontraditional providers

- Acceptance of a caregiver of the opposite gender

Cultural Diversity and Cultural Humility

Cultural diversity is a term used to describe cultural differences among people. See Figure 3.2[8] for artwork depicting diversity. While it is useful to be aware of specific traits of a culture or subculture, it is just as important to understand that each individual is unique and there are always variations in beliefs among individuals within a culture. Nurses should, therefore, refrain from making assumptions about the values and beliefs of members of specific cultural groups.[9] Instead, a better approach is recognizing that culture is not a static, uniform characteristic but instead realizing there is diversity within every culture and in every person. The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines cultural humility as, “A humble and respectful attitude toward individuals of other cultures that pushes one to challenge their own cultural biases, realize they cannot possibly know everything about other cultures, and approach learning about other cultures as a lifelong goal and process.”[10]

Current demographics in the United States reveal that the population is predominantly white. People who were born in another country, but now live in the United States, comprise approximately 14% of the nation’s total population. However, these demographics are rapidly changing. The United States Census Bureau projects that more than 50 percent of Americans will belong to a minority group by 2060. With an increasingly diverse population to care for, it is imperative for nurses to integrate culturally responsive care into their nursing practice.[11],[12] Creative a culturally responsive environment is discussed in a later subsection of this chapter.

Concepts Related to Culture

There are additional concepts related to culture that can impact a nurse’s ability to provide culturally responsive care, including stereotyping, ethnocentrism, discrimination, prejudice, and bias. See Table 3.2c for definitions and examples of these concepts.

Table 3.2c Concepts Related to Culture

| Concepts | Definitions | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Stereotyping | The assumption that a person has the attributes, traits, beliefs, and values of a cultural group because they are a member of that group. | The nurse teaches the daughter of an older patient how to make online doctor appointments, assuming that the older patient does not understand how to use a computer. |

| Ethnocentrism | The belief that one’s culture (or race, ethnicity, or country) is better and preferable than another’s. | The nurse disparages the patient’s use of nontraditional medicine and tells the patient that traditional treatments are superior. |

| Discrimination | The unfair and different treatment of another person or group, denying them opportunities and rights to participate fully in society. | A nurse manager refuses to hire a candidate for a nursing position because she is pregnant. |

| Prejudice | A prejudgment or preconceived idea, often unfavorable, about a person or group of people. | The nurse withholds pain medication from a patient with a history of opioid addiction. |

| Bias | An attitude, opinion, or inclination (positive or negative) towards a group or members of a group. Bias can be a conscious attitude (explicit) or an unconscious attitude where the person is not aware of their bias (implicit). | A patient does not want the nurse to care for them because the nurse has a tattoo. |

Race is a socially constructed idea because there are no true genetically- or biologically-distinct races. Humans are not biologically different from each other. Racism presumes that races are distinct from one another, and there is a hierarchy to race, implying that races are unequal. Ernest Grant, president of the American Nurses Association (ANA), recently declared that nurses are obligated “to speak up against racism, discrimination, and injustice. This is non-negotiable.”[13] As frontline health care providers, nurses have an obligation to recognize the impact of racism on their patients and the communities they serve.[14]

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Culture can exert a powerful influence on a person’s sexual orientation and gender expression. Sexual orientation refers to a person’s physical and emotional interest or desire for others. Sexual orientation is on a continuum and is manifested in one’s self-identity and behaviors.[15] The acronym LGBTQ stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or questioning in reference to sexual orientation. (A “+” is sometimes added after LGBTQ to capture additional orientations). See Figure 3.3[16] for an image of participants in a LGBTQ rally in Dublin. Historically, individuals within the LGBTQ community have experienced discrimination and prejudice from health care providers and avoided or delayed health care due to these negative experiences. Despite increased recognition of this group of people in recent years, members of the LGBTQ community continue to experience significant health disparities. Persistent cultural bias and stigmatization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBTQ) people have also been shown to contribute to higher rates of substance abuse and suicide rates in this population.[17],[18],[19]

Gender identity refers to a person’s inner sensibility that they are a man, a woman, or perhaps neither. Cisgender is the term used to describe a person whose identity matches their sex assigned at birth.[20] To the extent that a person’s gender identity does not conform with the sex assigned to them at birth, they may identify as transgender or as gender nonbinary. Transgender people, like cisgender people, “may be sexually oriented toward men, women, both sexes, or neither sex.”[21] Gender expression refers to a person’s outward demonstration of gender in relation to societal norms, such as in style of dress, hairstyle, or other mannerisms.[22]Sharing pronouns as part of a basic introduction to a patient can assist a transgender patient to feel secure sharing their pronouns in a health care setting. Asking a patient for their pronoun (he, she, they, ze, etc.) is considered part of a nursing assessment.

Related Ethical Considerations

Justice, a principle and moral obligation to act on the basis of equality and equity, is a standard linked to fairness for all in society.[23] The ANA states this obligation guarantees not only basic rights (respect, human dignity, autonomy, security, and safety) but also fairness in all operations of societal structures. This includes care being delivered with fairness, rightness, correctness, unbiasedness, and inclusiveness while being based on well-founded reason and evidence.[24]

Social justice is related to respect, equity, and inclusion. The ANA defines social justice as equal rights, equal treatment, and equitable opportunities for all.[25] The ANA further states, “Nurses need to model the profession’s commitment to social justice and health through actions and advocacy to address the social determinants of health and promote well-being in all settings within society.”[26] Social determinants of health are nonmedical factors that influence health outcomes, including conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider sets of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.[27] Health outcomes impacted by social determinants of health are referred to as health disparities. Health disparities are further discussed in a subsection later in this chapter.

- “Cultural diversity large.jpg” by მარიამ იაკობაძე is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Curtis, E., Jones, R., Tipene-Leach, D., Walker, C., Loring, B., Paine, S.-J., & Reid, P. (2019). Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: A literature review and recommended definition. International Journal for Equity in Health, 18, 174. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-1082-3 ↵

- Young, S., & Guo, K. (2016). Cultural diversity training: The necessity for cultural competence for healthcare providers and in nursing practice. The Health Care Manager, 35(2), 94-102. https://doi.org/10.1097/hcm.0000000000000100 ↵

- Campinha-Bacote, J. (2011). Coming to know cultural competence: An evolutionary process. International Journal for Human Caring, 15(3), 42-48. ↵

- Cole, N. L. (2018). How different cultural groups become more alike: Definition, overview and theories of assimilation. ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/assimilation-definition-4149483 ↵

- The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.(2015). Honoring the truth, reconciling for the future: A summary of the final report of the truth and reconciliation commission of Canada. http://www.trc.ca/assets/pdf/Honouring_the_Truth_Reconciling_for_the_Future_July_23_2015.pdf ↵

- Smith, A. (2007, March 26). Soul wound: The legacy of Native American schools. Amnesty International Magazine. https://web.archive.org/web/20121206131053/http://www.amnestyusa.org/node/87342 ↵

- “Pure_Diversity,_Mirta_Toledo_1993.jpg” by Mirta Toledo is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Young, S., & Guo, K. (2016). Cultural diversity training: The necessity for cultural competence for healthcare providers and in nursing practice. The Health Care Manager, 35(2), 94-102. https://doi.org/10.1097/hcm.0000000000000100 ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association ↵

- Young, S., & Guo, K. (2016). Cultural diversity training: The necessity for cultural competence for healthcare providers and in nursing practice. The Health Care Manager, 35(2), 94-102. https://doi.org/10.1097/hcm.0000000000000100 ↵

- Kaihlanen, A. M., Hietapakka, L., & Heponiemi, T. (2019) Increasing cultural awareness: Qualitative study of nurses’ perceptions about cultural competence training. BMC Nursing, 18(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-019-0363-x ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2020, June 1). ANA president condemns racism, brutality and senseless violence against black communities. https://www.nursingworld.org/news/news-releases/2020/ana-president-condemns-racism-brutality-and-senseless-violence-against-black-communities/ ↵

- Fulbright-Sumpter, D. (2020). “But I’m not racist ...” The nurse’s role in dismantling institutionalized racism. Texas Nursing, 94(3), 14–17. ↵

- Brydum, S. (2015, July 31). The true meaning of the word cisgender. The Advocate. https://www.advocate.com/transgender/2015/07/31/true-meaning-word-cisgender ↵

- “Dublin_LGBTQ_Pride_Festival_2013_-_LGBT_Rights_Matter_(9183564890).jpg” by infomatique is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 ↵

- Cole, N. L. (2018). How different cultural groups become more alike: Definition, overview and theories of assimilation. ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/assimilation-definition-4149483 ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-health ↵

- Chance, T. F. (2013). Going to pieces over LGBT health disparities: How an amended affordable care act could cure the discrimination that ails the LGBT community. Journal of Health Care Law and Policy, 16(2), 375–402. https://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1309&context=jhclp ↵

- Brydum, S. (2015, July 31). The true meaning of the word cisgender. The Advocate. https://www.advocate.com/transgender/2015/07/31/true-meaning-word-cisgender ↵

- Meerwijk, E. L., & Sevelius, J. M. (2017). Transgender population size in the United States: A meta-regression of population-based probability samples. American Journal of Public Health, 107(2), e1–e8. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303578 ↵

- Keuroghlian, A. S., Ard, K. L., & Makadon, H. J. (2017). Advancing health equity for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people through sexual health education and LGBT-affirming health care environments. Sexual Health, 14(1), 119–122. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH16145 ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association ↵

Patient Scenario

Mr. Hernandez is a 54-year-old patient admitted to the medical telemetry floor with a diagnosis of heart failure exacerbation. He tells the nurse, "My breathing has gotten worse the past last three days and I have a lot of swelling in my feet."

Applying the Nursing Process

Assessment: Vital signs at the start of shift were blood pressure 154/94, heart rate 88, respiratory rate 24, and oxygen saturation 88%. On assessment, the nurse finds fine crackles in bilateral posterior lower lung bases, an S3 heart sound, and 2+ pitting edema in bilateral lower extremities midway to the knee. The nurse reviews the patient's chart and discovers Mr. Hernandez has gained 10 pounds since his previous office visit last week.

Based on the assessment information that has been gathered, the nurse creates the following nursing care plan for Mr. Hernandez:

Nursing Diagnosis: Excess Fluid Volume related to compromised regulatory mechanism as evidenced by fine crackles in bilateral posterior lung bases, S3 heart sound, weight gain of 10 pounds in the past week, and the patient states, "My breathing has gotten worse the past last three days and I have a lot of swelling in my feet."

Overall Goal: The patient will demonstrate stabilization in fluid volume.

SMART Expected Outcomes:

- Mr. Hernandez's vital signs and weight will return to his baseline in the next 48 hours.

- Mr. Hernandez will verbalize three rules of dietary and fluid restriction to follow at home following his educational session.

Planning and Implementing Nursing Interventions:

The nurse will weigh the patient daily and analyze weight trends and 24-hour intake and output. The nurse will closely monitor lung sounds, respiratory rate, and oxygenation status. The nurse will establish a 24-hour schedule for fluid intake and educate the patient regarding fluid restriction. The nurse will closely monitor lab results, especially sodium and potassium, and monitor for symptoms of fluid shifts. The nurse will provide patient education regarding fluid and sodium restrictions.

Sample Documentation:

The patient was admitted with acute heart failure exacerbation and stated, "My breathing has gotten worse the past last three days and I have a lot of swelling in my feet." On admission to the unit at 0900, vital signs were blood pressure 154/94, heart rate 88, respiratory rate 24, and oxygen saturation 88%. Fine crackles were present in bilateral posterior lower lung bases, an S3 heart sound was present, and there was 2+ pitting edema in bilateral lower extremities midway to the knee. The chart indicates he has gained 10 pounds since his previous office visit last week. Provider orders and fluid restrictions were implemented. Lab results are within normal ranges. Patient education regarding fluid and sodium restrictions and a handout were provided. At the end of the session, Mr. Hernandez was able to report back three rules of dietary and fluid restrictions to follow at home when discharged.

Evaluation:

By the end of the shift, the second SMART outcome was "met" when Mr. Hernandez was able to report back three rules of dietary and fluid restrictions after the patient education session. The first SMART outcome was not yet met but will be reevaluated every shift for the next 24 hours.

Patient Scenario

Mr. Hernandez is a 54-year-old patient admitted to the medical telemetry floor with a diagnosis of heart failure exacerbation. He tells the nurse, "My breathing has gotten worse the past last three days and I have a lot of swelling in my feet."

Applying the Nursing Process

Assessment: Vital signs at the start of shift were blood pressure 154/94, heart rate 88, respiratory rate 24, and oxygen saturation 88%. On assessment, the nurse finds fine crackles in bilateral posterior lower lung bases, an S3 heart sound, and 2+ pitting edema in bilateral lower extremities midway to the knee. The nurse reviews the patient's chart and discovers Mr. Hernandez has gained 10 pounds since his previous office visit last week.

Based on the assessment information that has been gathered, the nurse creates the following nursing care plan for Mr. Hernandez:

Nursing Diagnosis: Excess Fluid Volume related to compromised regulatory mechanism as evidenced by fine crackles in bilateral posterior lung bases, S3 heart sound, weight gain of 10 pounds in the past week, and the patient states, "My breathing has gotten worse the past last three days and I have a lot of swelling in my feet."

Overall Goal: The patient will demonstrate stabilization in fluid volume.

SMART Expected Outcomes:

- Mr. Hernandez's vital signs and weight will return to his baseline in the next 48 hours.

- Mr. Hernandez will verbalize three rules of dietary and fluid restriction to follow at home following his educational session.

Planning and Implementing Nursing Interventions:

The nurse will weigh the patient daily and analyze weight trends and 24-hour intake and output. The nurse will closely monitor lung sounds, respiratory rate, and oxygenation status. The nurse will establish a 24-hour schedule for fluid intake and educate the patient regarding fluid restriction. The nurse will closely monitor lab results, especially sodium and potassium, and monitor for symptoms of fluid shifts. The nurse will provide patient education regarding fluid and sodium restrictions.

Sample Documentation:

The patient was admitted with acute heart failure exacerbation and stated, "My breathing has gotten worse the past last three days and I have a lot of swelling in my feet." On admission to the unit at 0900, vital signs were blood pressure 154/94, heart rate 88, respiratory rate 24, and oxygen saturation 88%. Fine crackles were present in bilateral posterior lower lung bases, an S3 heart sound was present, and there was 2+ pitting edema in bilateral lower extremities midway to the knee. The chart indicates he has gained 10 pounds since his previous office visit last week. Provider orders and fluid restrictions were implemented. Lab results are within normal ranges. Patient education regarding fluid and sodium restrictions and a handout were provided. At the end of the session, Mr. Hernandez was able to report back three rules of dietary and fluid restrictions to follow at home when discharged.

Evaluation:

By the end of the shift, the second SMART outcome was "met" when Mr. Hernandez was able to report back three rules of dietary and fluid restrictions after the patient education session. The first SMART outcome was not yet met but will be reevaluated every shift for the next 24 hours.

Learning Activities

(Answers to “Learning Activities” can be found in the “Answer Key” at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

Scenario A[1]

Mr. Smith, a 60-year-old male, was admitted to the general medical floor with a diagnosis of an exacerbation of heart failure. See Figure 15.17 for an image of Mr. Smith.[2] He has a past medical history of hypertension and coronary artery disease. His admitting weight was 225 pounds. His baseline weight from a previous clinic visit was 210 pounds. On admission, he had fine crackles throughout his lower posterior lobes and 4+ pitting edema in his lower extremities. His ABG results on admission were: pH 7.30, PaCO2 50 mmHg, PaO2 80 mm Hg, HCO3- 21 mEq/L, SaO2 85%.

Questions

- Interpret Mr. Smith's ABG results on admission.

- Explain the likely cause of the ABG results.

- Create a nursing diagnosis for Mr. Smith's fluid status in PES format based on his admission data.

Mr. Smith has received multiple doses of IV diuretics over the past three days since admission. During your morning assessment, Mr. Smith tells you he very thirsty and feels dizzy. You notice he is irritable and is becoming increasingly confused. You quickly obtain his vital signs: BP 85/45, HR 110, RR 24/minute, O2 saturation 98% on 2L/min per nasal cannula, and temperature 37.2 degrees Celsius. His lung sounds are clear and his heart sounds are regular sinus rhythm. You notice his weight this morning was 205 pounds. You call the provider and receive orders for STAT Basic Metabolic Panel and to initiate 0.9% Normal Saline IV fluids at 250 mL/hour until the provider arrives to evaluate the patient.

The Basic Metabolic Panel results (with the lab's normal reference range in parentheses) are:

Sodium: 155 mEq/L (135-145)

Potassium: 3.3 mEq/L (3.5-5.3)

Chloride: 103 mEq/L (98-108)

Carbon dioxide: 25 mEq/L (23-27)

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN): 30 mg/dL (10-25)

Creatinine: 1.9 mg/dL (0.5-1.5)

Glucose: 100 mg/dL (fasting 70-99)

Questions

4. What is Mr. Smith’s fluid balance this morning? Support your answer with data.

5. What is the probable cause of his fluid balance?

6. Interpret Mr. Smith's lab results. What are the potential causes of these results?

7. Create a nursing diagnosis statement in PES format for Mr. Smith's current fluid status.

8. Create a new expected outcome in SMART format for Mr. Smith.

9. In addition to providing intravenous fluids, what additional interventions will you implement for Mr. Smith?

10. How will you evaluate if the nursing interventions are effective?

Scenario B[3]

A 74-year-old male, Mr. M., was admitted to the general medical floor during the night shift with a diagnosis of pneumonia. See Figure 15.18 for an image of Mr. M.[4] He has a past medical history of alcohol abuse and coronary artery disease. You are the day shift nurse, and during your morning assessment you notice that Mr. M. becomes increasingly lethargic and is not following commands consistently. You obtain the following vital signs: BP 80/45, HR 110, RR 8 and labored, O2 saturation 80% on 3L per nasal cannula, temperature 38.1 degrees Celsius. His lung sounds reveal coarse crackles throughout, and you notice he is using accessory muscles with breathing. You notify the provider using an SBAR report and receive orders to increase oxygen to 10L per non-rebreather mask.

Lab results are ordered with the following results:

ABGs: pH 7.30, PaCO2 50, PaO2 59, HCO3 24, SaO2 80

Potassium: 5.9 mEq/L

Magnesium: 1.0 mEq/L

Calcium: 10.2 mg/dL

Sodium: 137 mEq/L

Hematocrit: 55%

Serum Osmolarity: 305 mmol/kg

BUN: 30 mg/dL

Urine Specific Gravity: 1.025

Questions:

- What is Mr. M.’s fluid balance? Provide data supporting the imbalance.

- What is your interpretation of Mr. M.’s ABGs?

- What is your interpretation of Mr. M.’s electrolyte studies?

- Is Mr. M. stable or unstable? Why?

- For what complications will you monitor?

- Write an SBAR communication you would have with the health care provider to notify them about Mr. M.’s condition.

- Create a NANDA-I diagnosis for Mr. M. in PES format.

- Identify an expected outcome for Mr. M. in SMART format.

- What interventions will you plan for Mr. M.?

- How will you evaluate if your interventions are effective?

- Write a nursing note about Mr. M.’s condition and your actions taken. This can be in the form of a DAR, SOAP, or summary nursing note.

Learning Activities

(Answers to “Learning Activities” can be found in the “Answer Key” at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

Scenario A[5]

Mr. Smith, a 60-year-old male, was admitted to the general medical floor with a diagnosis of an exacerbation of heart failure. See Figure 15.17 for an image of Mr. Smith.[6] He has a past medical history of hypertension and coronary artery disease. His admitting weight was 225 pounds. His baseline weight from a previous clinic visit was 210 pounds. On admission, he had fine crackles throughout his lower posterior lobes and 4+ pitting edema in his lower extremities. His ABG results on admission were: pH 7.30, PaCO2 50 mmHg, PaO2 80 mm Hg, HCO3- 21 mEq/L, SaO2 85%.

Questions

- Interpret Mr. Smith's ABG results on admission.

- Explain the likely cause of the ABG results.

- Create a nursing diagnosis for Mr. Smith's fluid status in PES format based on his admission data.

Mr. Smith has received multiple doses of IV diuretics over the past three days since admission. During your morning assessment, Mr. Smith tells you he very thirsty and feels dizzy. You notice he is irritable and is becoming increasingly confused. You quickly obtain his vital signs: BP 85/45, HR 110, RR 24/minute, O2 saturation 98% on 2L/min per nasal cannula, and temperature 37.2 degrees Celsius. His lung sounds are clear and his heart sounds are regular sinus rhythm. You notice his weight this morning was 205 pounds. You call the provider and receive orders for STAT Basic Metabolic Panel and to initiate 0.9% Normal Saline IV fluids at 250 mL/hour until the provider arrives to evaluate the patient.

The Basic Metabolic Panel results (with the lab's normal reference range in parentheses) are:

Sodium: 155 mEq/L (135-145)

Potassium: 3.3 mEq/L (3.5-5.3)

Chloride: 103 mEq/L (98-108)

Carbon dioxide: 25 mEq/L (23-27)

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN): 30 mg/dL (10-25)

Creatinine: 1.9 mg/dL (0.5-1.5)

Glucose: 100 mg/dL (fasting 70-99)

Questions

4. What is Mr. Smith’s fluid balance this morning? Support your answer with data.

5. What is the probable cause of his fluid balance?

6. Interpret Mr. Smith's lab results. What are the potential causes of these results?

7. Create a nursing diagnosis statement in PES format for Mr. Smith's current fluid status.

8. Create a new expected outcome in SMART format for Mr. Smith.

9. In addition to providing intravenous fluids, what additional interventions will you implement for Mr. Smith?

10. How will you evaluate if the nursing interventions are effective?

Scenario B[7]

A 74-year-old male, Mr. M., was admitted to the general medical floor during the night shift with a diagnosis of pneumonia. See Figure 15.18 for an image of Mr. M.[8] He has a past medical history of alcohol abuse and coronary artery disease. You are the day shift nurse, and during your morning assessment you notice that Mr. M. becomes increasingly lethargic and is not following commands consistently. You obtain the following vital signs: BP 80/45, HR 110, RR 8 and labored, O2 saturation 80% on 3L per nasal cannula, temperature 38.1 degrees Celsius. His lung sounds reveal coarse crackles throughout, and you notice he is using accessory muscles with breathing. You notify the provider using an SBAR report and receive orders to increase oxygen to 10L per non-rebreather mask.

Lab results are ordered with the following results:

ABGs: pH 7.30, PaCO2 50, PaO2 59, HCO3 24, SaO2 80

Potassium: 5.9 mEq/L

Magnesium: 1.0 mEq/L

Calcium: 10.2 mg/dL

Sodium: 137 mEq/L

Hematocrit: 55%

Serum Osmolarity: 305 mmol/kg

BUN: 30 mg/dL

Urine Specific Gravity: 1.025

Questions:

- What is Mr. M.’s fluid balance? Provide data supporting the imbalance.

- What is your interpretation of Mr. M.’s ABGs?

- What is your interpretation of Mr. M.’s electrolyte studies?

- Is Mr. M. stable or unstable? Why?

- For what complications will you monitor?

- Write an SBAR communication you would have with the health care provider to notify them about Mr. M.’s condition.

- Create a NANDA-I diagnosis for Mr. M. in PES format.

- Identify an expected outcome for Mr. M. in SMART format.

- What interventions will you plan for Mr. M.?

- How will you evaluate if your interventions are effective?

- Write a nursing note about Mr. M.’s condition and your actions taken. This can be in the form of a DAR, SOAP, or summary nursing note.

Let’s begin by reviewing the basic anatomy and physiology of the urinary and gastrointestinal systems.

Urinary System

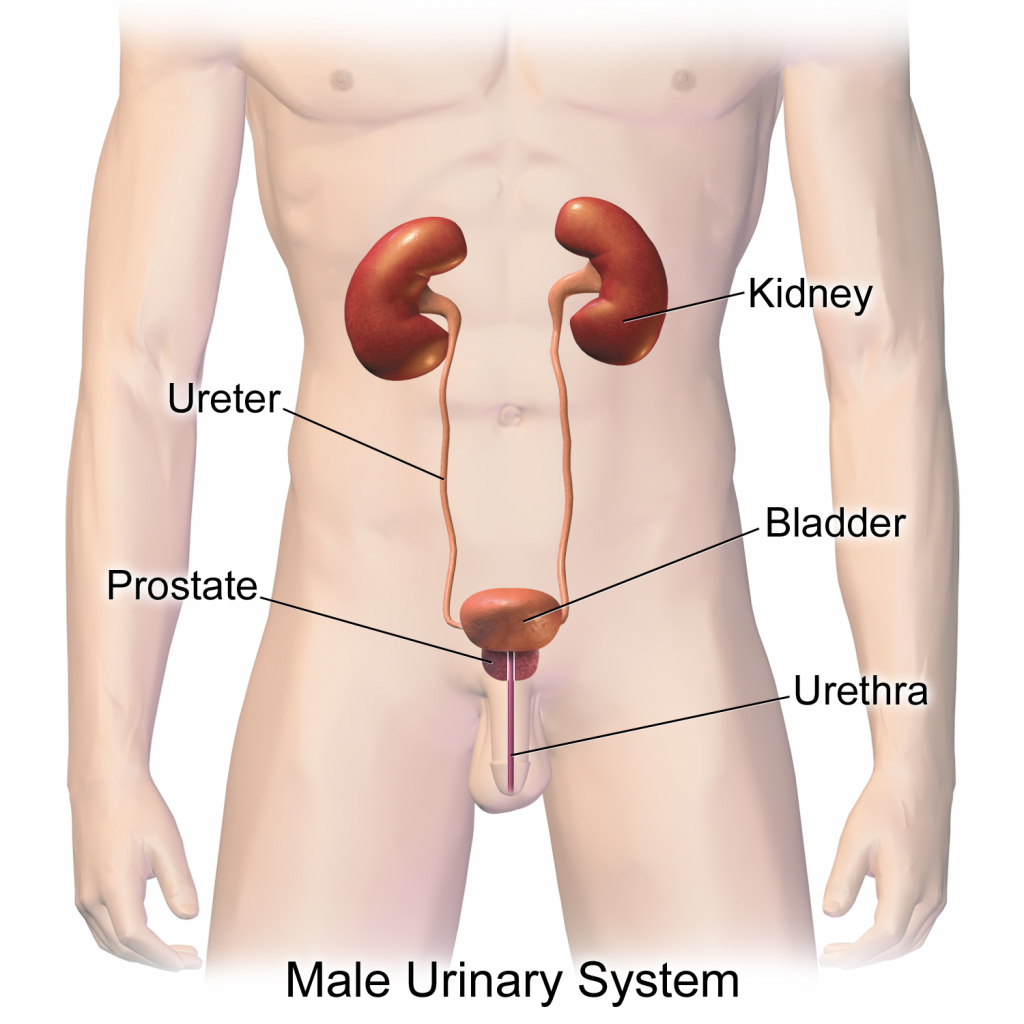

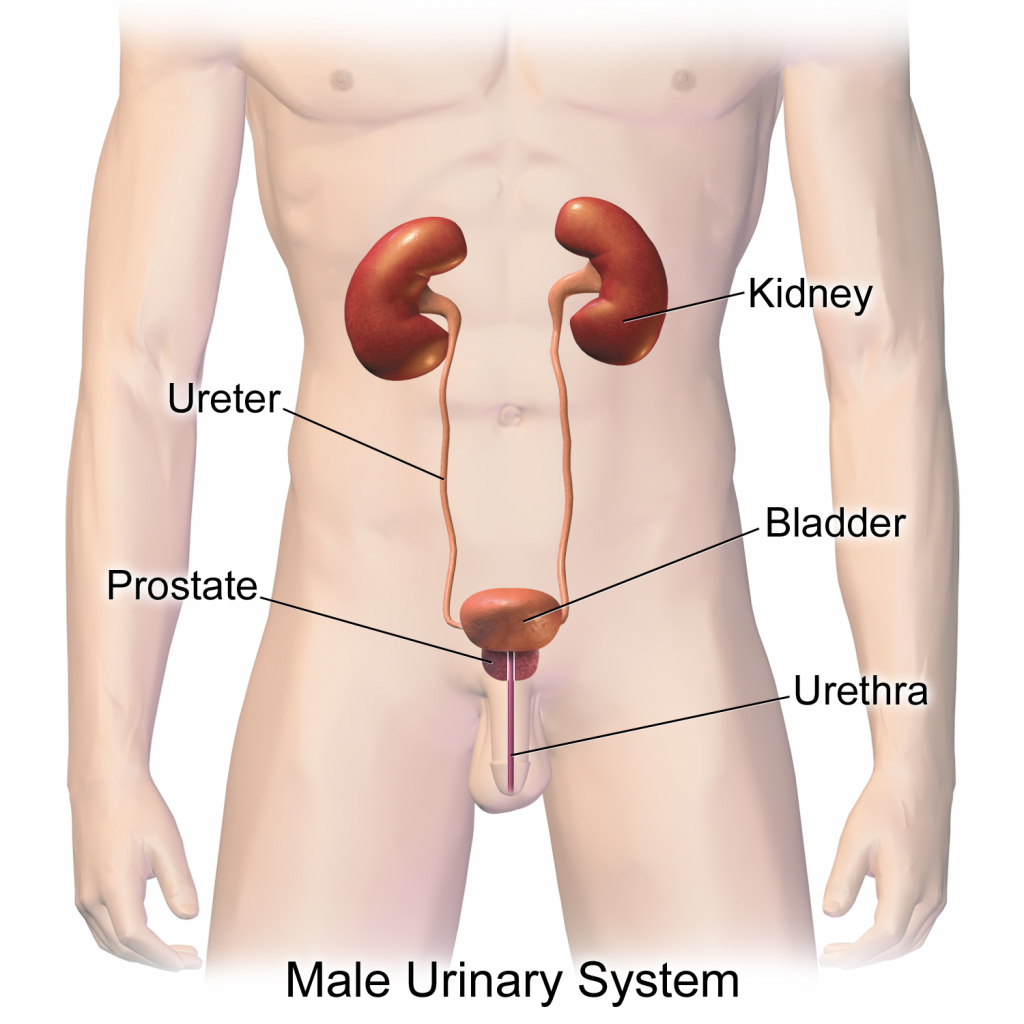

The urinary system, also referred to as the renal system or urinary tract, consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. The purpose of the urinary system is to eliminate waste from the body, regulate blood volume and blood pressure, control levels of electrolytes and metabolites, and regulate blood pH. The kidneys filter blood in the nephrons and remove waste in the form of urine. Urine exits the kidney via the ureters and enters the urinary bladder, where it is stored until it is expelled by urination (also referred to as voiding).[9] See Figure 16.1[10] for an image of the male urinary system. The female urinary system is similar except for a smaller urethra.

A healthy adult with normal kidney function produces 800-2,000 mL of urine per day, depending on fluid intake, as well as the amount of fluid lost through sweating and breathing. The bladder typically holds about 360-480 mL of urine. As the bladder fills, it sends signals to the brain that it is time to urinate. The urinary tract includes two sets of muscles that work together as a sphincter, closing off the urethra to keep urine in the bladder until the brain sends signals to urinate. Urination occurs when the brain sends signals to the wall of the bladder to contract and squeeze urine out of the bladder and through the urethra. Frequency of urination depends on how quickly the kidneys produce urine and how much urine a person’s bladder can comfortably hold.[11]

Normal urine should be clear, pale to light yellow in color, and not foul-smelling. However, some foods or medications may change the smell or color of urine. For instance, phenazopyridine (Pyridium), a common medication prescribed to treat the pain, frequency, and burning associated with urinary tract infections, can cause urine to appear orange.[12]

Nurses frequently monitor and document a patient’s urine output as part of the overall plan of care. It can be collected by placing a collection hat in the patient’s toilet and then measured in a graduated cylinder. If the patient has an indwelling catheter, the urine is emptied every shift from the catheter bag and measured in a graduated cylinder. For infants and toddlers, the number of daily wet diapers provides a general measure of urine output. For more specific measurement of urine output during hospitalization, wet diapers are weighed.

Terms commonly used to document conditions related to the urinary tract are as follows:

- Anuria: Absence of urine output, typically found during kidney failure, defined as less than 50 mL of urine over a 24-hour period.

- Dysuria: Painful or difficult urination.

- Frequency: The need to urinate several times during the day or at night (nocturia) in normal or less-than-normal volumes. It may be accompanied by a feeling of urgency.[13]

- Hematuria: Blood in the urine, either visualized or found during microscopic analysis.

- Oliguria: Decreased urine output, defined as less than 500 mL of urine in adults in a 24-hour period. In hospitalized patients, oliguria is further defined as less than 0.5 mL of urine per kilogram per hour for adults and children or less than 1 mL of urine per kilogram per hour for infants.[14] New oliguria should be reported to the health care provider because it can indicate dehydration, fluid retention, or decreasing kidney function.

- Nocturia: The need to get up at night on a regular basis to urinate. Nocturia often causes sleep deprivation that affects a person’s quality of life.[15]

- Polyuria: Greater than 2.5 liters of urine output over 24 hours, also referred to as diuresis. Urine is typically clear with no color.[16] New polyuria should be reported to the health care provider because it can be a sign of many medical conditions.

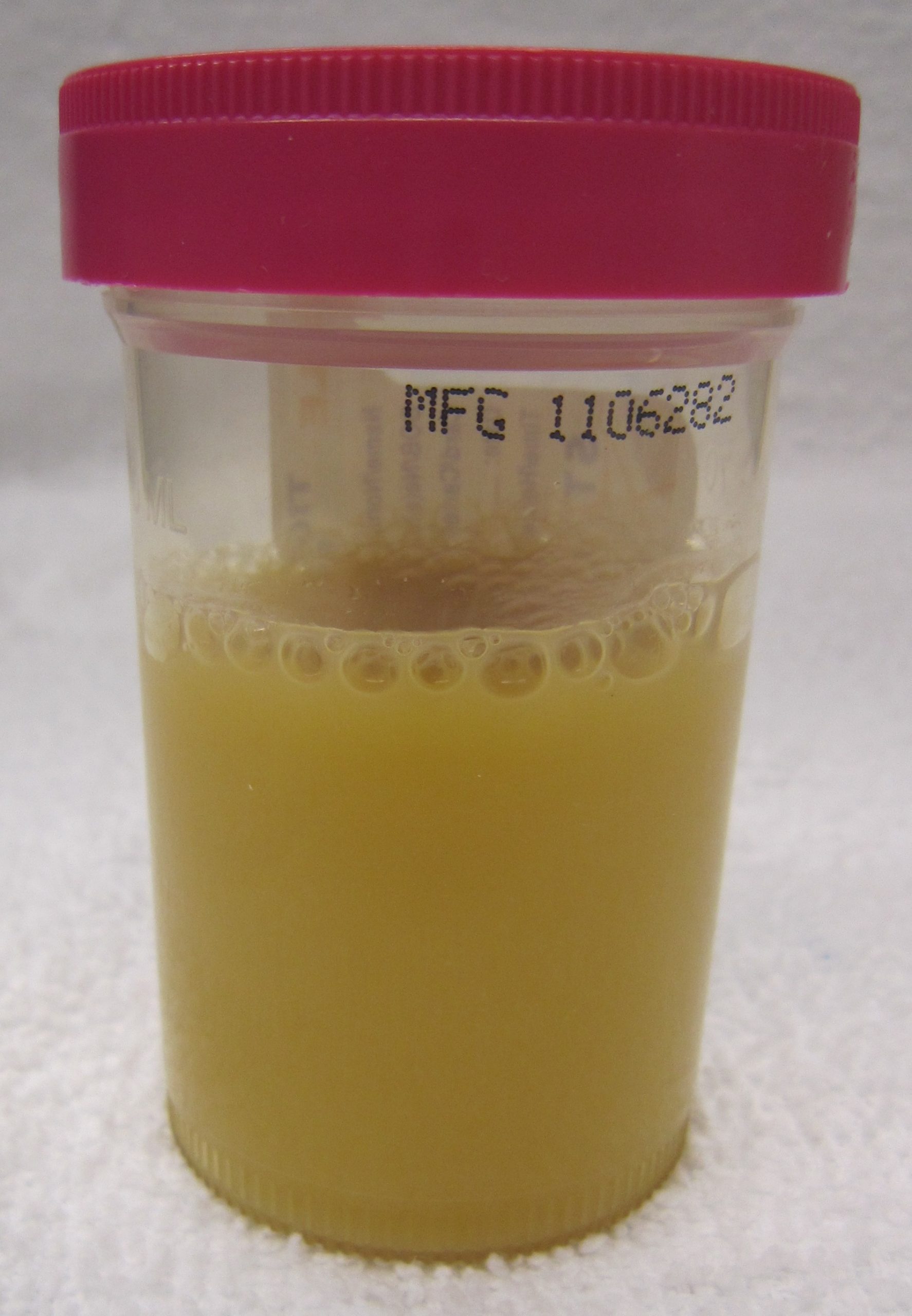

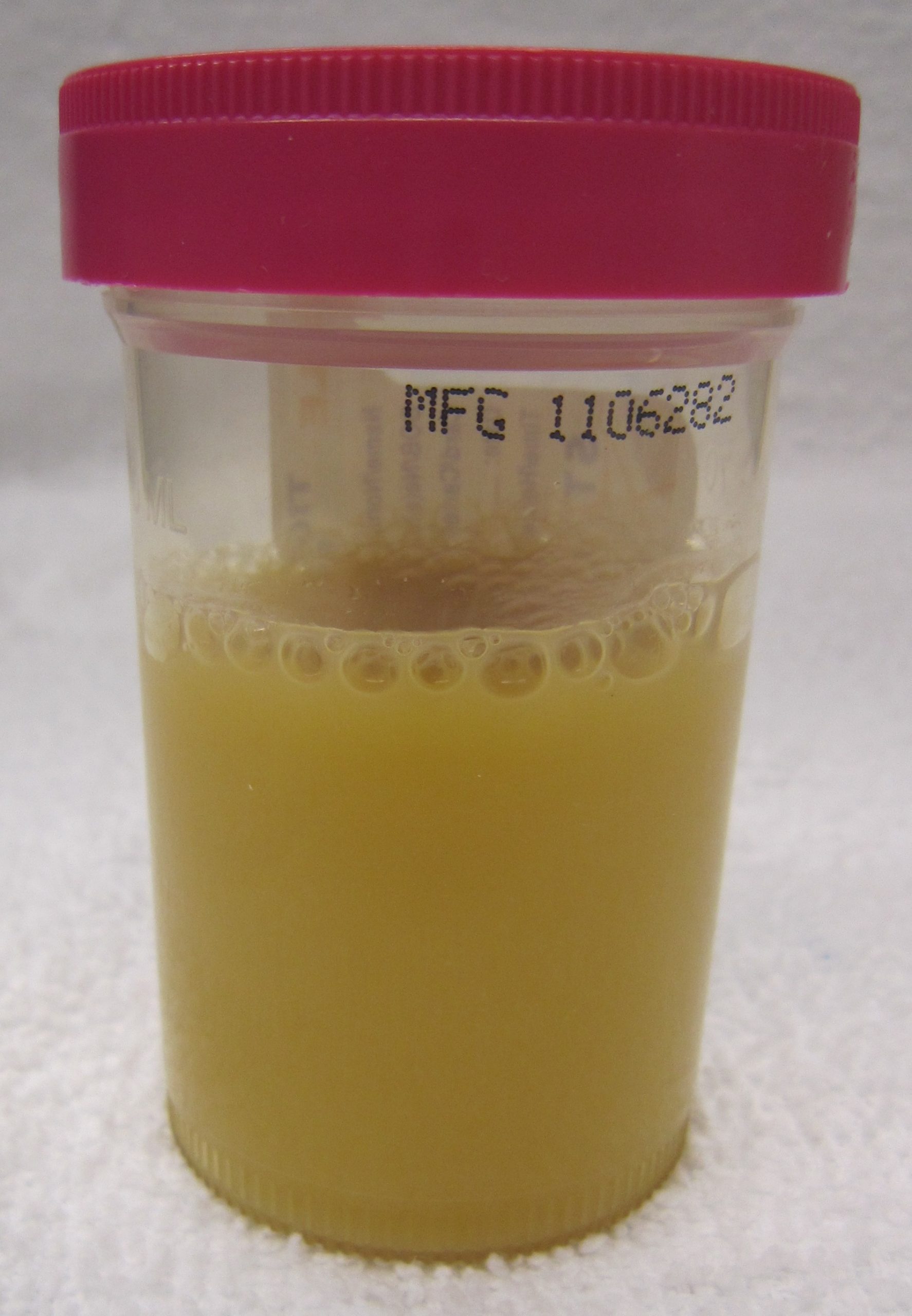

- Pyuria: At least ten white blood cells in each cubic millimeter of urine in a urine sample, typically indicating infection. In severe infections, pus may be visible in the urine.[17] See Figure 16.2[18] for an image of pyuria for a patient with urosepsis.

- Urgency: A sensation of an urgent need to void.[19] Urgency can cause urge incontinence if the patient is not able to reach the bathroom quickly.

View an activity reviewing the Vascular System of the Kidneys.

Gastrointestinal System

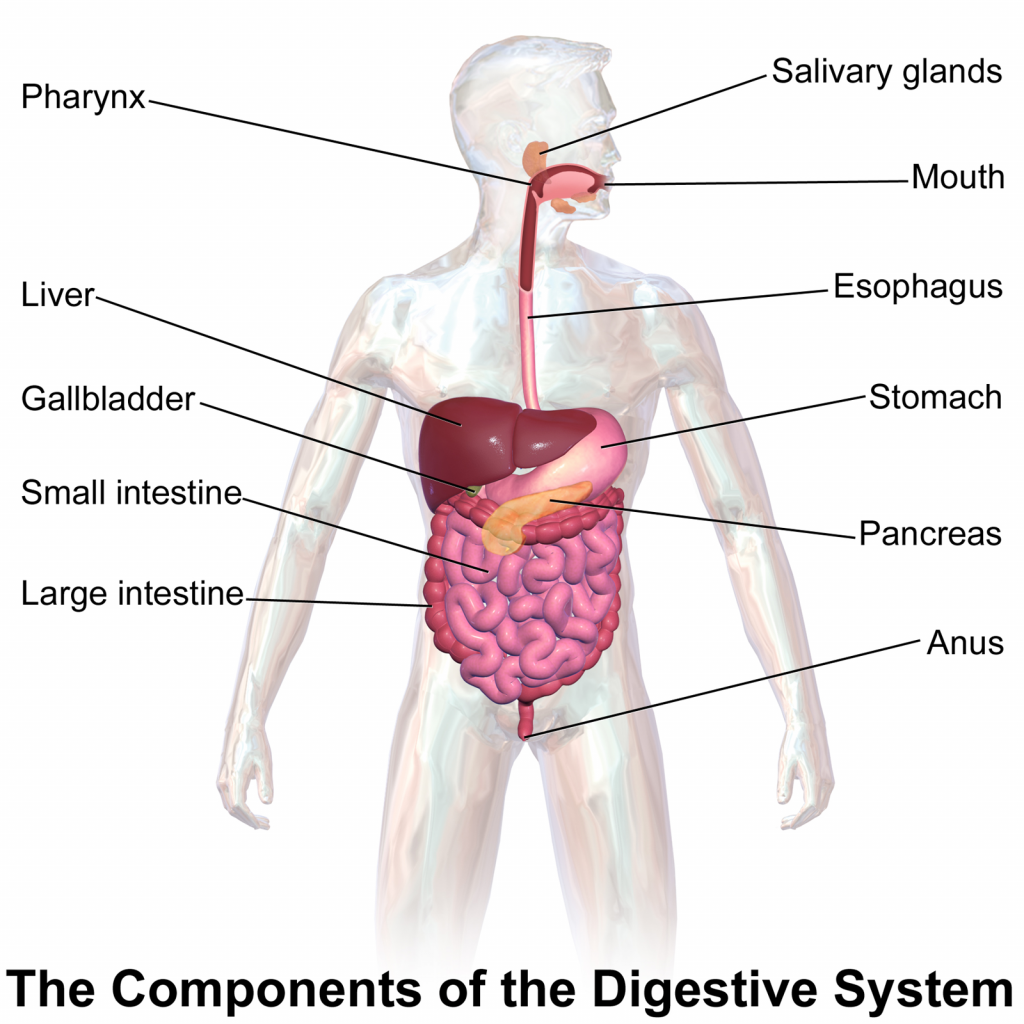

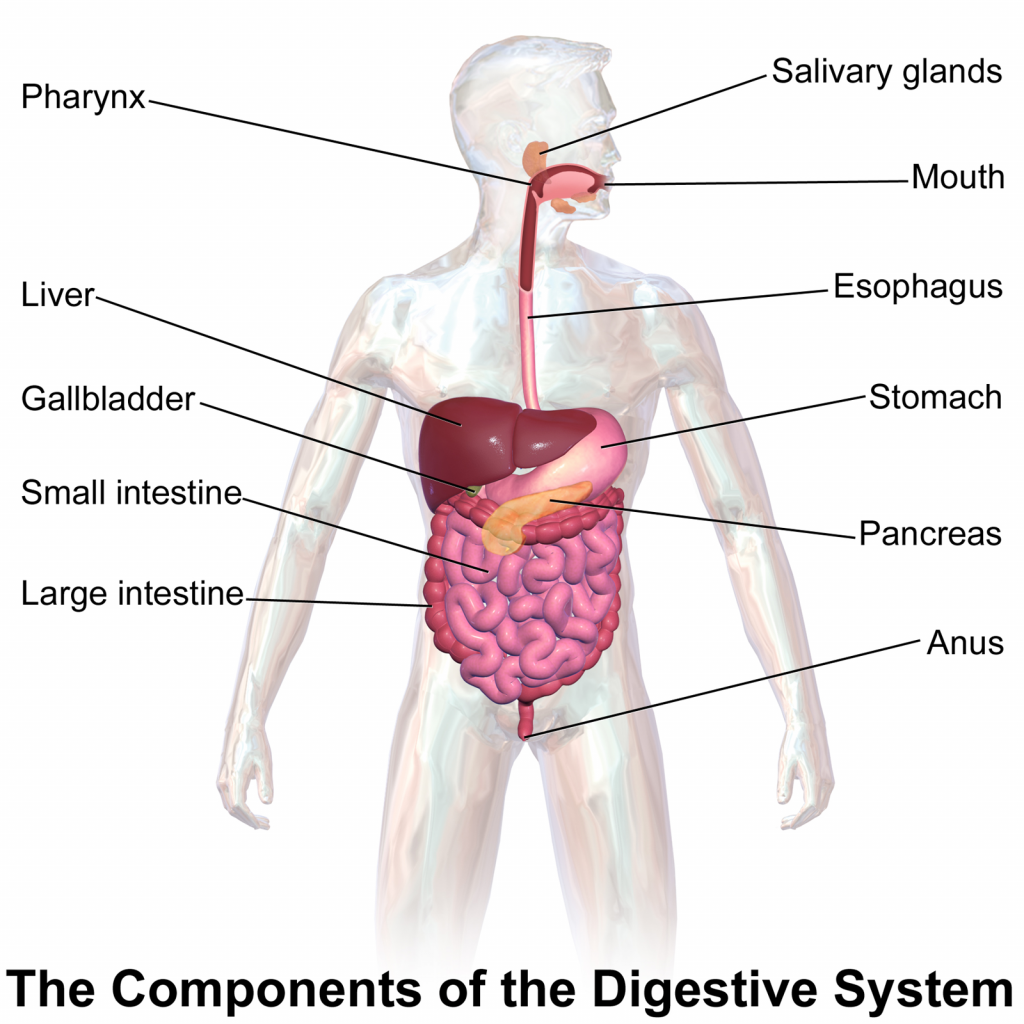

The gastrointestinal (GI) system includes the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and anus. See Figure 16.3[20] for an image of the gastrointestinal system. Ingested food and liquid are pushed through the GI tract by peristalsis, the involuntary contraction and relaxation of muscle creating wave-like movements of the intestines. The stomach mixes food and liquid with digestive enzymes and then empties into the small intestine. The muscles of the small intestine mix food with enzymes and bile from the pancreas, liver, and intestine and push the mixture forward for further digestion. Bacteria in the GI tract, called normal flora or microbiome, also assist with digestion. The walls of the small intestine absorb water and the digested nutrients into the bloodstream. As peristalsis continues, the waste products of the digestive process move into the large intestine. The large intestine absorbs water and changes the waste from liquid into stool. The rectum, at the lower end of the large intestine, stores stool until it is pushed out of the anus during a bowel movement.[21]

This section will focus on common alterations in bowel elimination, including constipation, diarrhea, and bowel incontinence. These alterations are common symptoms of several diseases and conditions of the gastrointestinal system. Nurses provide care to help manage these alterations.

Terms related to alterations in bowel elimination include the following:

- Black stools: Black-colored stools can be side effects of iron supplements or bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol).

- Rectal bleeding: Rectal bleeding refers to bright red blood in the stools, also referred to as hematochezia. It is a sign of bleeding from the lower GI tract. Rectal bleeding can range in severity from minimal drops of blood on the toilet tissue caused by hemorrhoids to severe bleeding in large amounts that are life-threatening and require emergency care.[22] New bleeding should always be reported to the health care provider.

- Tarry stools: Stools that are black, sticky, and appear like tar are referred to as melena. Melena is typically caused by bleeding in the upper part of the gastrointestinal tract, such as the esophagus, stomach, or the first part of the small intestine, or due to the patient swallowing blood. The blood appears darker and tarry-looking because it undergoes digestion on its way through the GI tract.[23] Bleeding from the upper part of the GI tract can also range from mild to life-threatening, depending upon the cause, and should always be reported to the health care provider.

Read information about the "Gastrointestinal" system in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

Newborns and Infants

Meconium refers to the first bowel movement of a newborn that appears sticky and black to dark green in color. See Figure 16.4[24] for an image of meconium. The stool of a breastfed baby usually appears like a curdled yellow, while that of a formula-fed baby is more pasty. Breastfed babies often have bowel movements after every feeding. Formula-fed babies tend to have fewer bowel movements.

Toddlers

Toddlers usually begin the process of toilet training between 2 and 3 years old. Enuresis is the term used to describe incontinence when sleeping (i.e., bed-wetting). Enuresis in children is considered normal unless it continues past 7 or 8 years of age, when it should be addressed with a pediatrician. Toddlers often have undigested food in their bowel movements due to the intestinal system not fully digesting some foods, such as corn or grapes.

Children

School-aged children may be at risk for developing constipation due to delaying bowel movements during school times until they are in the privacy of their homes.

Adults

Adult females often develop urinary incontinence related to pregnancy and delivery, menopause, or vaginal hysterectomy. Adults males may have urgency and urinary retention with possible overflow urinary incontinence as their prostate enlarges. Adults over the age of 30 may develop nocturia.

Older Adults

Peristalsis typically slows as aging occurs. Older adults should be encouraged to increase fluids, fiber, and activity, as appropriate, to prevent constipation. If a patient is not able to meet the goal of a bowel movement with soft, formed stools every three days, then a bowel management program should be initiated.

Now that we have reviewed the basic structure and function of the urinary and gastrointestinal systems, let’s review common alterations of urinary tract infection, urinary incontinence, urinary retention, constipation, diarrhea, and bowel incontinence in the following sections.

Let’s begin by reviewing the basic anatomy and physiology of the urinary and gastrointestinal systems.

Urinary System

The urinary system, also referred to as the renal system or urinary tract, consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. The purpose of the urinary system is to eliminate waste from the body, regulate blood volume and blood pressure, control levels of electrolytes and metabolites, and regulate blood pH. The kidneys filter blood in the nephrons and remove waste in the form of urine. Urine exits the kidney via the ureters and enters the urinary bladder, where it is stored until it is expelled by urination (also referred to as voiding).[25] See Figure 16.1[26] for an image of the male urinary system. The female urinary system is similar except for a smaller urethra.

A healthy adult with normal kidney function produces 800-2,000 mL of urine per day, depending on fluid intake, as well as the amount of fluid lost through sweating and breathing. The bladder typically holds about 360-480 mL of urine. As the bladder fills, it sends signals to the brain that it is time to urinate. The urinary tract includes two sets of muscles that work together as a sphincter, closing off the urethra to keep urine in the bladder until the brain sends signals to urinate. Urination occurs when the brain sends signals to the wall of the bladder to contract and squeeze urine out of the bladder and through the urethra. Frequency of urination depends on how quickly the kidneys produce urine and how much urine a person’s bladder can comfortably hold.[27]

Normal urine should be clear, pale to light yellow in color, and not foul-smelling. However, some foods or medications may change the smell or color of urine. For instance, phenazopyridine (Pyridium), a common medication prescribed to treat the pain, frequency, and burning associated with urinary tract infections, can cause urine to appear orange.[28]

Nurses frequently monitor and document a patient’s urine output as part of the overall plan of care. It can be collected by placing a collection hat in the patient’s toilet and then measured in a graduated cylinder. If the patient has an indwelling catheter, the urine is emptied every shift from the catheter bag and measured in a graduated cylinder. For infants and toddlers, the number of daily wet diapers provides a general measure of urine output. For more specific measurement of urine output during hospitalization, wet diapers are weighed.

Terms commonly used to document conditions related to the urinary tract are as follows:

- Anuria: Absence of urine output, typically found during kidney failure, defined as less than 50 mL of urine over a 24-hour period.

- Dysuria: Painful or difficult urination.

- Frequency: The need to urinate several times during the day or at night (nocturia) in normal or less-than-normal volumes. It may be accompanied by a feeling of urgency.[29]

- Hematuria: Blood in the urine, either visualized or found during microscopic analysis.

- Oliguria: Decreased urine output, defined as less than 500 mL of urine in adults in a 24-hour period. In hospitalized patients, oliguria is further defined as less than 0.5 mL of urine per kilogram per hour for adults and children or less than 1 mL of urine per kilogram per hour for infants.[30] New oliguria should be reported to the health care provider because it can indicate dehydration, fluid retention, or decreasing kidney function.

- Nocturia: The need to get up at night on a regular basis to urinate. Nocturia often causes sleep deprivation that affects a person’s quality of life.[31]

- Polyuria: Greater than 2.5 liters of urine output over 24 hours, also referred to as diuresis. Urine is typically clear with no color.[32] New polyuria should be reported to the health care provider because it can be a sign of many medical conditions.

- Pyuria: At least ten white blood cells in each cubic millimeter of urine in a urine sample, typically indicating infection. In severe infections, pus may be visible in the urine.[33] See Figure 16.2[34] for an image of pyuria for a patient with urosepsis.

- Urgency: A sensation of an urgent need to void.[35] Urgency can cause urge incontinence if the patient is not able to reach the bathroom quickly.

View an activity reviewing the Vascular System of the Kidneys.

Gastrointestinal System

The gastrointestinal (GI) system includes the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and anus. See Figure 16.3[36] for an image of the gastrointestinal system. Ingested food and liquid are pushed through the GI tract by peristalsis, the involuntary contraction and relaxation of muscle creating wave-like movements of the intestines. The stomach mixes food and liquid with digestive enzymes and then empties into the small intestine. The muscles of the small intestine mix food with enzymes and bile from the pancreas, liver, and intestine and push the mixture forward for further digestion. Bacteria in the GI tract, called normal flora or microbiome, also assist with digestion. The walls of the small intestine absorb water and the digested nutrients into the bloodstream. As peristalsis continues, the waste products of the digestive process move into the large intestine. The large intestine absorbs water and changes the waste from liquid into stool. The rectum, at the lower end of the large intestine, stores stool until it is pushed out of the anus during a bowel movement.[37]

This section will focus on common alterations in bowel elimination, including constipation, diarrhea, and bowel incontinence. These alterations are common symptoms of several diseases and conditions of the gastrointestinal system. Nurses provide care to help manage these alterations.

Terms related to alterations in bowel elimination include the following:

- Black stools: Black-colored stools can be side effects of iron supplements or bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol).

- Rectal bleeding: Rectal bleeding refers to bright red blood in the stools, also referred to as hematochezia. It is a sign of bleeding from the lower GI tract. Rectal bleeding can range in severity from minimal drops of blood on the toilet tissue caused by hemorrhoids to severe bleeding in large amounts that are life-threatening and require emergency care.[38] New bleeding should always be reported to the health care provider.

- Tarry stools: Stools that are black, sticky, and appear like tar are referred to as melena. Melena is typically caused by bleeding in the upper part of the gastrointestinal tract, such as the esophagus, stomach, or the first part of the small intestine, or due to the patient swallowing blood. The blood appears darker and tarry-looking because it undergoes digestion on its way through the GI tract.[39] Bleeding from the upper part of the GI tract can also range from mild to life-threatening, depending upon the cause, and should always be reported to the health care provider.

Read information about the "Gastrointestinal" system in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

Newborns and Infants

Meconium refers to the first bowel movement of a newborn that appears sticky and black to dark green in color. See Figure 16.4[40] for an image of meconium. The stool of a breastfed baby usually appears like a curdled yellow, while that of a formula-fed baby is more pasty. Breastfed babies often have bowel movements after every feeding. Formula-fed babies tend to have fewer bowel movements.

Toddlers

Toddlers usually begin the process of toilet training between 2 and 3 years old. Enuresis is the term used to describe incontinence when sleeping (i.e., bed-wetting). Enuresis in children is considered normal unless it continues past 7 or 8 years of age, when it should be addressed with a pediatrician. Toddlers often have undigested food in their bowel movements due to the intestinal system not fully digesting some foods, such as corn or grapes.

Children

School-aged children may be at risk for developing constipation due to delaying bowel movements during school times until they are in the privacy of their homes.

Adults

Adult females often develop urinary incontinence related to pregnancy and delivery, menopause, or vaginal hysterectomy. Adults males may have urgency and urinary retention with possible overflow urinary incontinence as their prostate enlarges. Adults over the age of 30 may develop nocturia.

Older Adults

Peristalsis typically slows as aging occurs. Older adults should be encouraged to increase fluids, fiber, and activity, as appropriate, to prevent constipation. If a patient is not able to meet the goal of a bowel movement with soft, formed stools every three days, then a bowel management program should be initiated.

Now that we have reviewed the basic structure and function of the urinary and gastrointestinal systems, let’s review common alterations of urinary tract infection, urinary incontinence, urinary retention, constipation, diarrhea, and bowel incontinence in the following sections.

A urinary tract infection (UTI) is a common infection that occurs when bacteria, typically from the rectum, enter the urethra and infect the urinary tract. Infections can affect several parts of the urinary tract, but the most common type is a bladder infection (cystitis). Kidney infections (pyelonephritis) are more serious than a bladder infection because they can have long-lasting effects on the kidneys.[41]

Some people are at higher risk of getting a UTI. UTIs are more common in females because their urethras are shorter and closer to the rectum, which makes it easier for bacteria to enter the urinary tract. Other factors that can increase the risk of UTIs include the following:

- A previous UTI

- Sexual activity, especially with a new sexual partner

- Pregnancy

- Age (Older adults and young children are at higher risk. Refer to the "Care of the Older Adult" chapter for more details about older adults.)

- Structural problems in the urinary tract, such as prostate enlargement[42]

Symptoms of a UTI include the following:[43]

- Pain or burning while urinating (dysuria)

- Frequent urination (frequency)

- Urgency with small amounts of urine

- Bloody urine

- Pressure or cramping in the groin or lower abdomen

- Confusion or altered mental status in older adults

Symptoms of a more serious kidney infection (pyelonephritis) include fever above 101 degrees F (38.3 degrees C), shaking chills, lower back pain or flank pain (i.e., on the sides of the back), and nausea or vomiting.[44] It is important to remember that older adults with a UTI may not exhibit these symptoms but often demonstrate an increased level of confusion. Sometimes UTIs can spread to the blood (septicemia), leading to life-threatening infection called sepsis. Read more about sepsis in the “Infection” chapter.

When a patient presents with symptoms of a UTI, the provider will order diagnostic tests, such as a urine dip, urinalysis, or urine culture. Read more about diagnostic tests in the “Assessment” section of the "Nursing Process" chapter.

Interventions

Antibiotics are prescribed for urinary tract infections. Nurses provide important patient education to patients with a UTI, such as the importance of finishing their antibiotic therapy as prescribed, even if they begin to feel better after a few days. Patients should also be encouraged to drink extra fluids to help flush bacteria from the urinary tract. Additional patient education regarding preventing future UTIs includes the following:

- Urinate after sexual activity.

- Stay well-hydrated and urinate regularly.

- Take showers instead of baths.

- Minimize douching, sprays, or powders in the genital area.

- Teach girls when potty training to wipe front to back.[45]

A urinary tract infection (UTI) is a common infection that occurs when bacteria, typically from the rectum, enter the urethra and infect the urinary tract. Infections can affect several parts of the urinary tract, but the most common type is a bladder infection (cystitis). Kidney infections (pyelonephritis) are more serious than a bladder infection because they can have long-lasting effects on the kidneys.[46]

Some people are at higher risk of getting a UTI. UTIs are more common in females because their urethras are shorter and closer to the rectum, which makes it easier for bacteria to enter the urinary tract. Other factors that can increase the risk of UTIs include the following:

- A previous UTI

- Sexual activity, especially with a new sexual partner

- Pregnancy

- Age (Older adults and young children are at higher risk. Refer to the "Care of the Older Adult" chapter for more details about older adults.)

- Structural problems in the urinary tract, such as prostate enlargement[47]

Symptoms of a UTI include the following:[48]

- Pain or burning while urinating (dysuria)

- Frequent urination (frequency)

- Urgency with small amounts of urine

- Bloody urine

- Pressure or cramping in the groin or lower abdomen

- Confusion or altered mental status in older adults

Symptoms of a more serious kidney infection (pyelonephritis) include fever above 101 degrees F (38.3 degrees C), shaking chills, lower back pain or flank pain (i.e., on the sides of the back), and nausea or vomiting.[49] It is important to remember that older adults with a UTI may not exhibit these symptoms but often demonstrate an increased level of confusion. Sometimes UTIs can spread to the blood (septicemia), leading to life-threatening infection called sepsis. Read more about sepsis in the “Infection” chapter.

When a patient presents with symptoms of a UTI, the provider will order diagnostic tests, such as a urine dip, urinalysis, or urine culture. Read more about diagnostic tests in the “Assessment” section of the "Nursing Process" chapter.

Interventions

Antibiotics are prescribed for urinary tract infections. Nurses provide important patient education to patients with a UTI, such as the importance of finishing their antibiotic therapy as prescribed, even if they begin to feel better after a few days. Patients should also be encouraged to drink extra fluids to help flush bacteria from the urinary tract. Additional patient education regarding preventing future UTIs includes the following:

- Urinate after sexual activity.

- Stay well-hydrated and urinate regularly.

- Take showers instead of baths.

- Minimize douching, sprays, or powders in the genital area.

- Teach girls when potty training to wipe front to back.[50]

Urinary incontinence is the involuntary loss of urine. Although abnormal, it is a common symptom that can seriously affect the physical, psychological, and social well-being of affected individuals of all ages. It has been estimated that 1 in 5 women develop urinary incontinence, but many are too embarrassed to discuss the condition with their health care providers. Some believe it’s a normal part of aging that they have to live with. The result can be isolation and depression when they limit their activities and social interactions because of embarrassment due to incontinence. Nurses can greatly improve the quality of life for these patients by assessing for incontinence in a sensitive manner and then providing patient education about methods to prevent and/or manage incontinence.

Types of Urinary Incontinence

Continence is achieved through an interplay of the physiology of the bladder, urethra, sphincter, pelvic floor, and the nervous system coordinating these organs.[51] A disruption in any of these areas can cause several types of urinary incontinence.

- Stress urinary incontinence is the involuntary loss of urine with intra-abdominal pressure (e.g., laughing and coughing) or physical exertion (e.g., jumping). It is caused by weak pelvic floor muscles that is often the result of pregnancy and vaginal delivery, menopause, and vaginal hysterectomy.[52]

- Urge urinary incontinence (also referred to as “overactive bladder”) is urine leakage caused by the sensation of a strong desire to void (urgency). It can be caused by increased sensitivity to stimulation by the detrusor muscle in the bladder or decreased inhibitory control of the central nervous system.[53]

- Mixed urinary incontinence is a mix of urinary frequency, urgency, and stress incontinence.[54]

- Overflow incontinence occurs when small amounts of urine leak from a bladder that is always full. This condition tends to occur in males with enlarged prostates that prevent the complete emptying of the bladder.[55]

- Functional incontinence occurs in older adults who have normal bladder control but have a problem getting to the toilet because of arthritis or other disorders that make it hard to move quickly or manipulate zippers or buttons. Patients with dementia also have increased risk for functional incontinence.

It is important to understand the types of incontinence so that appropriate interventions can be targeted to the cause.

Assessment of Incontinence

Assessment begins with screening questions during a health history, including questions such as, “Do you have any problems with the leakage or dribbling of urine? Do you ever have problems making it to the bathroom in time?” If a patient responds “Yes” to either of these questions, it is helpful to encourage them to start a voiding diary to record their urination habits and activities. The voiding diary should include the following:

- When and how much the patient urinates

- Urinary leakage and what the patient was doing when it happened (for example, running, biking, laughing)

- Sudden urges to urinate

- How often the patient wakes at night to use the bathroom

- Type and volume of food and beverages and the time of intake

- Medication use, such as diuretics, and the timing of administration

- Any pain or problems experienced before, during, and after urinating (for example, sudden urges, difficulty urinating, dribbling urine, feeling as if the bladder is never empty, weak urine flow).[56]

The provider will review information from the voiding diary, perform a physical assessment, and likely order diagnostic testing, such as a urine dip to check for a urinary tract infection, and urodynamic diagnostic testing that includes a variety of tests about bladder function, including filling, urine storage, and emptying.[57] Individualized treatment will be based on the assessment and tests to assess any structural abnormalities and bladder function.

Interventions

Nurses should use therapeutic communication with patients experiencing urinary incontinence to help them feel comfortable in expressing their fears, worries, and embarrassment about incontinence and work toward improving their quality of life. Let them know they’re not alone and that urinary incontinence is not something they have to live with. Provide education about pelvic floor muscle training exercises, timed voiding, lifestyle modification, and incontinence products. Encourage them to learn more about their condition so they can optimally manage it and improve their quality of life.[58]

Nurses play an important role in educating patients about bladder control training to prevent incontinence. Bladder control training includes several these techniques:

- Pelvic muscle exercises (also known as Kegel exercises) work the muscles used to stop urination, which can help prevent stress incontinence. Learn more about pelvic floor exercises in the box below.

- Timed voiding can be used to help a patient regain control of the bladder. Timed voiding encourages the patient to urinate on a set schedule, for example, every hour, whether they feel the urge to urinate or not. The time between bathroom trips is gradually extended with the general goal of achieving four hours between voiding. Timed voiding helps to control urge and overflow incontinence as the brain is trained to be less sensitive to the sensation of the bladder walls expanding as they fill.[59]

- Lifestyle changes can help with incontinence. Losing weight, drinking less caffeine (found in coffee, tea, and many sodas), preventing constipation, and avoiding lifting heavy objects may help with incontinence. Limiting fluid intake before bedtime and scheduling prescribed diuretic medication in the morning or early afternoon are also helpful.[60]

- Protective products may be needed to protect the skin from breakdown and prevent leakage onto clothing. Incontinence underwear has a waterproof liner and built-in cloth pad to absorb large amounts of urine to protect skin from moisture and control odor. It is available in daytime and nighttime styles (designed to hold more urine). A product resembling a tampon is another option for females. It is made of absorbent fibers that support the urethra and prevents accidental leaks but doesn’t inhibit urination and won’t move or fall out during bowel movements.[61]

Teaching Pelvic Floor Exercises

Kegel exercises are designed to make your pelvic floor muscles stronger. Your pelvic floor muscles hold up your bladder and prevent it from leaking urine.

- Start by finding the right muscles. There are two easy ways to do this: stop the stream of urine as you are urinating or imagine that you are trying to stop the passage of gas. Squeeze the muscles you would use to do both. If you sense a "pulling" feeling, you are squeezing the right muscles for pelvic exercises. Many people have trouble finding the right muscles. A doctor, nurse, or therapist can check to make sure you are doing the exercises correctly and targeting the correct muscles.

- Find a quiet spot to practice so you can concentrate. Lie on the floor. Pull in the pelvic muscles and hold for a count of 3. Then relax for a count of 3. Work up to 10 to 15 repeats each time you exercise.

- Complete pelvic exercises at least three times a day. Try to use three different positions while performing the exercises: lying down, sitting, and standing. For example, you can exercise while lying on the floor, sitting at a desk, or standing in the kitchen. Using all three positions while exercising makes these muscles their strongest.

- Be patient. Most people notice an improvement after a few weeks, but the maximum effect may take up to 3-6 weeks.

View a YouTube video about Kegel Exercises[62] from Michigan Medicine.

Patient education regarding other treatment options may be provided:

- Biofeedback uses sensors to help a patient become more aware of signals from the body to regain control over the muscles in their bladder and urethra.[63] Mechanical devices, such as pessaries, support the urethra and can support vaginal prolapse to prevent or reduce urinary leakage. They come in various sizes and are professionally fitted by trained health care providers. They should be removed, cleaned, and reinserted regularly to prevent infection. Some of the devices, such as ring pessaries, can be removed and reinserted by the patient. They are similar to a diaphragm and can be removed or left in place for sexual intercourse.[64]

- Anticholinergic medications, such as oxybutynin, may be prescribed to treat urge urinary incontinence and mixed urinary incontinence. They block the action of acetylcholine and provide an antispasmodic effect on smooth muscle to relieve symptoms. However, side effects include dry mouth, constipation, dizziness, and drowsiness, which can increase fall risk in older adults.

- If bladder training and medications are not effective, surgery may be performed, such as a sling procedure or a bladder neck suspension.[65]

Active transport: Movement of solutes and ions across a cell membrane against a concentration gradient from an area of lower concentration to an area of higher concentration using energy during the process.

Chvostek’s sign: An assessment sign of acute hypocalcemia characterized by involuntary facial muscle twitching when the facial nerve is tapped.

Diffusion: The movement of solute particles from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration.

Edema: Swelling caused by excessive interstitial fluid retention.

Extracellular fluids (ECF): Fluids found outside cells in the intravascular or interstitial spaces.

Filtration: Movement of fluids through a permeable membrane utilizing hydrostatic pressure.

Hydrostatic pressure: The pressure that a contained fluid exerts on what is confining it.

Hypercapnia: Elevated levels of retained carbon dioxide in the body.

Hypertonic solution: Intravenous fluids with a higher concentration of dissolved particles than blood plasma.

Hypervolemia: Excess intravascular fluid. Used interchangeably with “excessive fluid volume.”

Hypotonic solution: Intravenous fluids with a lower concentration of dissolved particles than blood plasma.

Hypovolemia: Intravascular fluid loss. Used interchangeably with “deficient fluid volume” and “dehydration.”

Interstitial fluids: Fluids found between the cells and outside of the vascular system.

Intracellular fluids (ICF): Fluids found inside cells consisting of protein, water, and electrolytes.

Intravascular fluids: Fluids found in the vascular system consisting of the body’s arteries, veins, and capillary networks.

Isotonic solution: Intravenous fluids with a similar concentration of dissolved particles as blood plasma.

Oncotic pressure: Pressure inside the vascular compartment created by protein content of the blood (in the form of albumin) that holds water inside the blood vessels.

Osmolality: Proportion of dissolved particles in a specific weight of fluid.

Osmolarity: Proportion of dissolved particles or solutes in a specific volume of fluid.

Osmosis: Movement of fluid through a semipermeable membrane from an area of lesser solute concentration to an area of greater solute concentration.

Passive transport: Movement of fluids or solutes down a concentration gradient where no energy is used during the process.

Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS): A body system that regulates extracellular fluids and blood pressure by regulating fluid output and electrolyte excretion.

Trousseau’s sign: A sign associated with hypocalcemia that causes a spasm of the hand when a blood pressure cuff is inflated.

Urine specific gravity: A measurement of hydration status that measures the concentration of particles in urine.

Active transport: Movement of solutes and ions across a cell membrane against a concentration gradient from an area of lower concentration to an area of higher concentration using energy during the process.

Chvostek’s sign: An assessment sign of acute hypocalcemia characterized by involuntary facial muscle twitching when the facial nerve is tapped.

Diffusion: The movement of solute particles from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration.

Edema: Swelling caused by excessive interstitial fluid retention.

Extracellular fluids (ECF): Fluids found outside cells in the intravascular or interstitial spaces.

Filtration: Movement of fluids through a permeable membrane utilizing hydrostatic pressure.

Hydrostatic pressure: The pressure that a contained fluid exerts on what is confining it.

Hypercapnia: Elevated levels of retained carbon dioxide in the body.

Hypertonic solution: Intravenous fluids with a higher concentration of dissolved particles than blood plasma.

Hypervolemia: Excess intravascular fluid. Used interchangeably with “excessive fluid volume.”

Hypotonic solution: Intravenous fluids with a lower concentration of dissolved particles than blood plasma.

Hypovolemia: Intravascular fluid loss. Used interchangeably with “deficient fluid volume” and “dehydration.”

Interstitial fluids: Fluids found between the cells and outside of the vascular system.

Intracellular fluids (ICF): Fluids found inside cells consisting of protein, water, and electrolytes.

Intravascular fluids: Fluids found in the vascular system consisting of the body’s arteries, veins, and capillary networks.

Isotonic solution: Intravenous fluids with a similar concentration of dissolved particles as blood plasma.

Oncotic pressure: Pressure inside the vascular compartment created by protein content of the blood (in the form of albumin) that holds water inside the blood vessels.

Osmolality: Proportion of dissolved particles in a specific weight of fluid.

Osmolarity: Proportion of dissolved particles or solutes in a specific volume of fluid.

Osmosis: Movement of fluid through a semipermeable membrane from an area of lesser solute concentration to an area of greater solute concentration.

Passive transport: Movement of fluids or solutes down a concentration gradient where no energy is used during the process.

Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS): A body system that regulates extracellular fluids and blood pressure by regulating fluid output and electrolyte excretion.

Trousseau’s sign: A sign associated with hypocalcemia that causes a spasm of the hand when a blood pressure cuff is inflated.

Urine specific gravity: A measurement of hydration status that measures the concentration of particles in urine.

Learning Objectives

- Assess factors that put a patient at risk for alterations in urinary and bowel elimination

- Identify factors related to alterations in elimination across the life span

- Outline the data that must be collected for identification of alterations in bowel/urine elimination

- Base decisions on the interpretation of basic diagnostic tests of urinary and bowel elimination: urinalysis and occult blood

- Detail the nonpharmacologic measures to promote urinary and bowel elimination

- Identify evidence-based practices

After ingesting food and fluids, our body eliminates waste products through the urinary system and the gastrointestinal system. Nurses provide care for patients with commonly occuring elimination alterations, including urinary tract infections, urinary incontinence, urinary retention, constipation, diarrhea, and bowel incontinence. This chapter will provide an overview of these alterations and the associated nursing care.

Learning Objectives

- Assess factors that put a patient at risk for alterations in urinary and bowel elimination

- Identify factors related to alterations in elimination across the life span

- Outline the data that must be collected for identification of alterations in bowel/urine elimination

- Base decisions on the interpretation of basic diagnostic tests of urinary and bowel elimination: urinalysis and occult blood

- Detail the nonpharmacologic measures to promote urinary and bowel elimination

- Identify evidence-based practices

After ingesting food and fluids, our body eliminates waste products through the urinary system and the gastrointestinal system. Nurses provide care for patients with commonly occuring elimination alterations, including urinary tract infections, urinary incontinence, urinary retention, constipation, diarrhea, and bowel incontinence. This chapter will provide an overview of these alterations and the associated nursing care.