Spirituality

18.3 Common Religions and Spiritual Practices

It can be helpful for nurses to learn basic knowledge about common religions and religious practices as they support their patients’ beliefs. This section will review basic elements of common religions and religious practices.

Religious Classifications

For centuries, humankind has sought to understand and explain the “meaning of life.” Many philosophers believe this contemplation and the desire to understand our place in the universe are what differentiate humankind from other species. Religion, in one form or another, has been found in all human societies since human societies first appeared.[1]

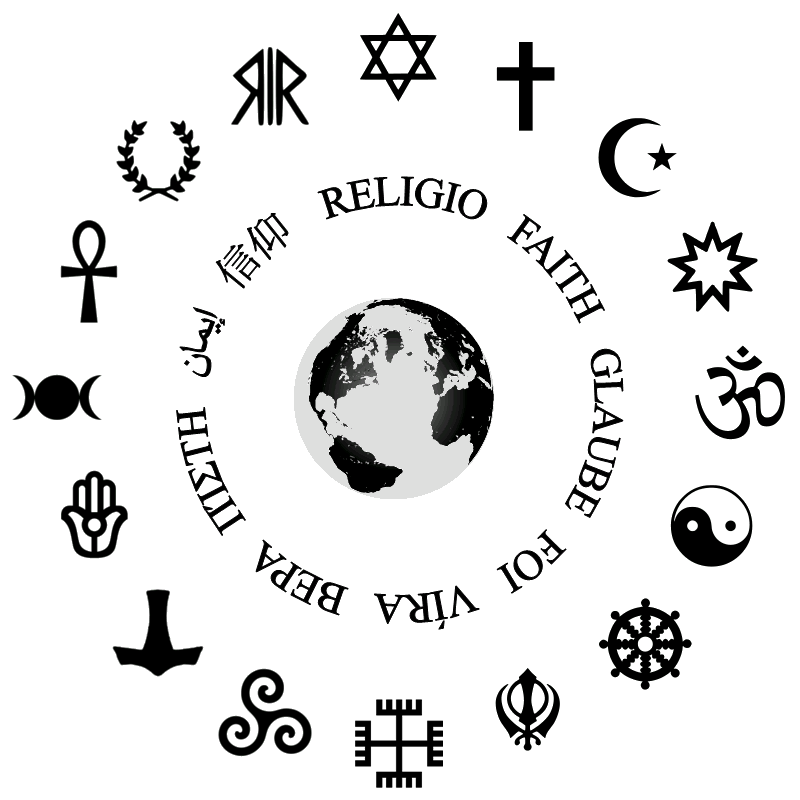

Religion is a unified system of beliefs, values, and practices that a person holds sacred or considers to be spiritually significant. Spiritual practices often unite a moral community called a church. Some people associate religion with a place of worship (e.g., a synagogue or church), a practice (e.g., attending religious services, being baptized, or receiving communion), or a concept that guides one’s daily life (e.g., sin or kharma).[2] See Figure 18.3[3] for an illustration of symbols from many worldwide religions.

The symbols are arranged in clockwise order starting at the 12:00 position: Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Bahá’í faith, Hinduism, Taoism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Rodnoveril, Celtic paganism, Heathenism, Semitic paganism, Wicca, Kemetism, Hellenic paganism, and Roman paganism.

Religions

Religions have been classified based on what or whom people worship (if anything). See Table 18.3 for a list of religious classifications.[4]

Table 18.3 Religious Classifications[5]

| Religious Classification | What/Who Is Divine | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Polytheism | Multiple gods | Belief systems of the ancient Greeks and Romans |

| Monotheism | Single god | Judaism, Christianity, Islam |

| Atheism | Nothing | Atheism |

| Animism | Nonhuman beings (animals, plants, natural world) | Indigenous nature worship |

| Totemism | Human-natural being connection | Native American beliefs |

Every culture has atheists who do not believe in a divine being or entity and agnostics who hold that ultimate reality (such as God) is unknowable. However, being a nonbeliever in a divine being does not mean the individual has no morality. For example, many Nobel Peace Prize winners have classified themselves as atheists or agnostics.[6]

Monotheism includes the religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. People who practice Judaism are called Jews, people who practice Christianity are called Christians, and people who practice Islam are called Muslims. Jews, Christians, and Muslims believe in many of the same historical sacred stories, referred to by Christians as the “Old Testament.” In these shared sacred stories, it is believed that the son of God (a messiah) will return to save God’s followers. While Christians believe that the messiah has already appeared in the person of Jesus Christ, Jews and Muslims believe the messiah has yet to appear.[7]

The following subsections describe the general beliefs of five worldwide religions. However, as with all cultural beliefs, nurses should recognize an individual’s specific spiritual values, beliefs, and practices and not assume they believe in these elements based on the religion they profess.

Judaism

After their exodus from slavery in Egypt in the thirteenth century B.C., Jews became a nomadic society worshipping only one God. The Jewish covenant, a promise of a special relationship with Yahweh (God), is an important element of Judaism. The sacred text of Judaism is the Torah, which contains the same sacred stories in the first five books of the Christian’s Bible. Talmud is a collection of additional sacred Jewish oral interpretations of the Torah. Jews emphasize moral behavior and action in life.[8] Jewish religious services are held in a synagogue. See Figure 18.4[9] for an image of the Torah and the Star of David, a traditional symbol of Judaism.

Christianity

Christianity began over 2,000 years ago in Palestine with the birth of a Jew named Jesus Christ. Jesus was a charismatic leader and believed by Christians to be the son of God, who taught his followers to treat others as one would like to be treated. The sacred text for Christians is the Bible that includes the “Old Testament” and the “New Testament.” The New Testament describes the life and teachings of Jesus.[10] Christians attend religious services in a church or cathedral. See Figure 18.5[11] for an image of a sculpture depicting Jesus Christ crucified on a cross, a common symbol of Christianity.

Christianity is broadly split into three branches: Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox. The Catholic branch is governed by the Pope and many bishops around the world. There are many different denominations of Protestant faiths, such as Lutherans, Baptists, Presbyterians, Methodists, Seventh-Day Adventists, Pentecostals, and Mormons. Although all Christians believe the Bible is a sacred text, different denominations have variations in their sacred texts. For example, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints uses the Book of Mormon that they believe details other parts of Christian doctrine and Jesus’ life that aren’t included in the Bible. Similarly, the Catholic Bible includes a collection of stories that were part of the King James translation created in 1611 but are no longer included in Protestant versions of the Bible.[12]

Although monotheistic, Christians often describe God through three manifestations called the Holy Trinity: the father (God), the son (Jesus), and the Holy Spirit, similar to how water can be in different forms of ice, water, and gas. Another foundation to Christian faith is the Ten Commandments, a set of rules that includes acts considered sinful, such as theft, murder, and adultery.[13]

Islam

Islam is monotheistic religion that follows the teaching of the prophet Muhammad, born in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, in 570 C.E. Muhammad is viewed as a prophet and a messenger of Allah (God), who is divine. The followers of Islam are called Muslims who attend religious services in mosques.[14] See Figure 18.6[15] for an image of a mosque.

Islam means “peace” and “submission.” The sacred text for Muslims is the Qur’an (or Koran).

Muslims are guided by five beliefs and practices, often called pillars of their faith, including believing that Allah is the only god and Muhammad is his prophet, participating in daily prayer, helping those in poverty, fasting as a spiritual practice, and participating in pilgrimage to the holy center of Mecca.[16]

Hinduism

Hinduism originated in the Indus River Valley about 4,500 years ago in what is now modern-day northwest India and Pakistan. Hindus believe in a divine power that can manifest as different entities. Three main incarnations, Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva, are sometimes compared to the Christian belief in the Holy Trinity.[17]

Multiple sacred texts, collectively called the Vedas, contain hymns and rituals from ancient India and are mostly written in Sanskrit. Hindus believe in a set of principles called dharma that refer to one’s duty in the world and correspond with “right” actions. Hindus also believe in karma, the notion that spiritual ramifications of one’s actions are balanced cyclically in this life or a future life (referred to as reincarnation).[18] Most Hindus observe religious rituals at home. The rituals vary greatly among regions, villages, and individuals. See Figure 18.7[19] for a statue of Shiva in a yogic meditation. Yoga is a Hindu discipline that trains the body, mind, and consciousness for health, tranquility, and spiritual insight.

Buddhism

Buddhism is a philosophy founded by Siddhartha Gautama around 500 B.C.E. Siddhartha is believed to have given up a comfortable, upper-class life to follow one of poverty and spiritual devotion. At the age of thirty-five, he famously meditated under a sacred fig tree and vowed not to rise before he achieved enlightenment, called bodhi. After this experience, he became known as Buddha or “enlightened one.” Followers were drawn to Buddha’s teachings and the practice of meditation, and he later established a monastic order.[20]

Buddha’s teachings encourage Buddhists to lead a moral life by accepting the four Noble Truths: life is suffering, suffering arises from attachment to desires, suffering ceases when attachment to desires ceases, and freedom from suffering is possible by following the “middle way.” The concept of the “middle way” is central to Buddhist thinking and encourages people to live in the present, practice acceptance of others, and accept personal responsibility.[21] See Figure 18.8[22] for a statue of the enlightenment of Buddha.

Common Religious Beliefs and Practices

Now that we have reviewed the basic beliefs of various world religions, this section describes common religious beliefs and practices that may impact nursing care. As always, customize nursing interventions according to each patient’s specific values, practices, and beliefs.

Buddhist Patients

- Buddhism places strong emphasis on “mindfulness,” so patients may request peace and quiet for the purpose of meditation, especially during crises.

- Some Buddhists may express strong, culturally-based concerns about modesty (for instance, regarding treatment by someone of the opposite sex).

- Some Buddhists are strictly vegetarian and refuse to consume any meat or animal by-product. For such patients, even medications that are produced using animals are likely to be problematic. See Figure 18.9[23] for an image of a vegetarian meal in a Buddhist temple.

- The importance of mindful awareness of all of life’s experience may affect patients’ or family members’ decisions about pain medications out of worry that analgesics may unduly cloud awareness. Nonpharmacological pain management options are often attractive.

- Patients or families may pray or chant out loud repetitiously. This is often done quietly, and any noise concerns in a hospital can usually be negotiated easily. Families sometimes wish to place a picture of the Buddha in the patient’s room.

- In end-of-life care, Buddhists may be very concerned about safeguarding their awareness/consciousness. Clarification of the patient’s wishes about the use of analgesics in the days and hours before death is strategically important for developing an ethical pain management plan.

- As a patient approaches death, medical and nursing staff should minimize actions that might disturb their concentration or meditation in preparation for dying. Near the time of death, a Buddhist patient’s family may appear quite emotionally reserved and even keep their physical distance from the patient’s bed. This can be a custom for the purpose of supporting the patient’s desire to concentrate without distraction on the experience of dying.

- After the patient has died, staff should try to keep the body as still as possible and avoid jostling during transport. Buddhism teaches that the body is not immediately devoid of the person’s spirit after death, so there is continued concern about disturbing the body. Such belief may also be an impediment to discussion of organ donation.

- Families may request that after a patient has died the patient’s body be kept available to them for a number of hours for the purpose of religious rites. All such requests should be negotiated carefully, maximizing the opportunity for accommodation in recognition of the religious significance.[24]

Catholic Patients

- Sacraments and blessings by a Catholic priest can be viewed as highly important, especially before surgery or as a perceived risk of death.

- If a patient is near death, there may be an urgent request for a Catholic priest to offer “Sacrament of the Sick” (which some Catholics may call “Last Rites”). Even if the sacrament has already been offered, there may still be a request for a priest to offer prayers and bless the patient.

- All requests for the sacrament of baptism should be relayed to a Catholic priest. However, if an infant is likely to die before a priest can arrive, the infant may be baptized by any person with proper intent. The person would say, “[name of infant], I baptize you in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit,” pouring a small amount of water over the infant’s head three times. Emergency baptisms are reported to the local Catholic parish priest.

- Patients may request Holy Communion (Eucharist) prior to surgery. While a Catholic priest or Eucharistic Minister would typically offer such a patient only a tiny portion of a wafer, patients who are NPO (to have nothing by mouth) should have this request approved by the care team as medically safe.

- Some patients may keep religious objects with them, such as a rosary (a loop of beads with a crucifix used for prayer), a scapula (a small cloth devotional pendant), or a religious medal. See Figure 18.10[25] for an image of a rosary. If patients request that such an object remain with them during medical procedures, discuss the option of placing the object in a sealed bag that can be kept on or near the patient. If an object is metal and the patient is having a radiological procedure or test (like an MRI scan), ask the patient or family if they can bring in a nonmetal substitute.

- Interruption of religious practices, such as regular attendance at Mass or special observance of special holy days, may be highly stressful to Catholic patients. Discuss contacting clergy and/or a hospital chaplain.

- Patients may have moral questions about treatment decisions such as the withholding/withdrawing of life-sustaining treatment. A priest can offer authoritative guidance in specific situations.

- Patients may request non-meat diets, especially during the time of Lent (the 40 days before the festival of Easter).[26]

Hindu Patients

- Hindu patients may express strong, culturally-based concerns about modesty, especially regarding treatment by someone of the opposite sex. Genital and urinary issues are often not discussed with a spouse present.

- Hindus are often strictly vegetarian and do not consume meat or animal by-products. For such patients, even medications that are produced using animals are likely to be problematic. Some Hindus may also refrain from eating certain vegetables, like onions or garlic.

- Fasting is a common practice in Hinduism, and patients may wish to discuss the implications in light of the medical/dietary care plan.

- The act of washing is generally conceived as requiring running water, either from a tap or (poured) from a pitcher. A patient may have a strong desire to wash their hands after meals. See Figure 18.11[27] for an image of a Hindu worshipping with water.

- For many Hindu patients, there is a cultural norm to use the right hand for “clean” tasks like eating (often without utensils) and their left hand for “unclean” tasks like toileting. Medical and nursing staff should consider this right-left significance before hindering a patient’s hand or arm movement in any way. Discuss these preferences with the patient.

- Patients may wear jewelry or adornments that have strong cultural and religious meaning, and staff should not remove these without discussing the matter with the patient or family.

- Hinduism teaches that death is a crucial “transition” with karmic implications. There may be a strong desire that death occurs in the home rather than in the hospital. Family may wish to perform a number of pre-death rituals (for example, tying a thread around the person’s neck or wrist). After death, family members may request to wash the patient’s body (by family members of the same sex as the patient).

- Family may request constant attendance of the deceased’s body. A family member or representative may wish to accompany the body to the morgue (where the person may sit outside any restricted area yet relatively near the body).[28]

Jehovah’s Witness Patients

- The most defining tenant for Jehovah’s Witnesses in health care is the strict prohibition against receiving blood (i.e., red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets, or plasma) by transfusion (even the transfusion of a patient’s stored blood), in medication using blood products, or in food. Some blood fractions (such as albumin, immunoglobulin, and hemophiliac preparations) are allowed, but patients are guided by their own conscience.

- Organ donation and transplantation are allowed, but patients are guided by their own conscience.

- Jehovah’s Witnesses are usually well-prepared to work with health care providers to seek all possible options for treatment that do not conflict with religious concerns. It is very common for adults to carry a card at all times stating religiously-based directives for treatment without blood.

- Contrary to popular misconceptions, faith-healing is not a part of Jehovah’s Witness tradition. Prayers are often said for comfort and endurance.

- Tradition of Jehovah’s Witnesses does not teach that those who die experience an immediate afterlife. It would be inappropriate to say to the family of a deceased patient, “He’s in a better place now.”

- Jehovah’s Witnesses do not celebrate birthdays or Christian “holidays.”[29]

Jewish Patients

- Some Jewish patients may strictly observe a rule not to “work” on the Sabbath (from sundown on Friday until sundown on Saturday) or on religious holidays. If so, this religious injunction against “work,” including prohibitions against using certain tools or engaging in tasks that initiate use of electricity, can prevent tasks like writing, flipping a light switch, pushing buttons to call a nurse, adjusting a motorized bed, or operating a patient controlled analgesia (PCA) pump. The tearing of paper can be considered “work,” so roll toilet paper may need to be replaced with an opened box of individual sheets. Medical procedures should not be scheduled during the Sabbath or religious holidays (unless they are life-saving) nor should hospital discharges be planned during such times without the consent of the patient. While these restrictions on “work” are generally associated with Orthodox Judaism, they may be important for any Jewish patient.

- Jewish holidays are usually highly significant for patients, especially Passover in the spring and Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur in the fall. These holidays may affect the scheduling of medical procedures and may involve dietary changes (related to a need for special food or to a desire to fast). All Jewish holidays run from sundown-to-sundown.

- Jewish patients often request a special Kosher diet in accordance with religious laws that govern the preparation of certain foods (e.g., beef), the prohibition of certain foods (e.g., pork and gelatin), or the combination of some food (e.g., beef served with dairy products). During the holiday of Passover, an important distinction is made between food that is merely “Kosher” and that which is specifically “Kosher for Passover.” Hand washing before eating may have a religious significance.

- Some Jewish patients may have culturally-based concerns about modesty, especially regarding treatment by someone of the opposite sex. However, because Jewish tradition holds the expertise of medical practitioners in high regard, this may reduce concerns about treatment by the opposite sex.

- Questions about the withholding or withdrawing of life-sustaining therapy are deeply debated within Judaism, and some Jews are strongly opposed to the idea. Family members often wish to consult with a rabbi about the specific circumstances and decisions regarding end-of-life care.

- After a patient has died, Jewish tradition directs that burial happen quickly and that there be no autopsy (unless the autopsy is deemed necessary by a mandate from the Medical Examiner). Also, the family may request that a family member or representative constantly accompany the body in the hospital or even to the morgue (where the person may sit outside any restricted area yet relatively near the body) to say prayers and read psalms.

- There may be a request that amputated limbs be made available for burial. Details should be arranged through the patient’s/family’s funeral home.

- Jewish religious laws pose a complex set of restrictions that can affect medical decisions, and patients or family members may request to speak with a rabbi to determine the moral propriety of any particular decision. Exceptions are often made when an action is understood in terms of “saving a life,” such as emergency surgery or organ donation during the Sabbath. The value of “saving a life” is held in extremely high regard in Jewish tradition.

- It is common for male Jewish patients to wear a yarmulke or kippah (skull cap) during prayer, and some Jews may wish to keep them on at all times. Patients or family members may wear prayer shawls and use phylacteries (two small boxes containing scriptural verses and having leather straps, worn on the forehead and forearm during prayer). There may be a request that at least ten people (called a minyan) be allowed in the patient’s room for prayer. See Figure 18.12[30] for an image of a skull cap worn during prayer.

- A Jewish person need not be religious to identify culturally as “Jewish” and may observe Jewish religious traditions for cultural reasons.

- The word “Jew” is commonly used within Jewish culture, but non-Jews should be mindful of its complex historical connotations that can sometimes be perceived as disrespectful when spoken by non-Jews.[31]

Muslim Patients

- Muslim patients may express strong concerns about modesty, especially regarding treatment by someone of the opposite sex. A Muslim woman may need to cover her body completely and should always be given time and opportunity to do so before anyone enters her room. Women may also request that a family member be present during an exam and may desire to remain clothed during an exam if at all possible. Muslim men may find examination by a woman to be extremely challenging. Nudity is emphatically discouraged. There should be no casual physical contact by non-family members of the opposite sex (such as shaking hands). Some Muslims may avoid eye contact as a function of modesty.

- Muslims may specifically request a diet in accordance with religious laws for “Halal” food, though many Muslims opt for a vegetarian diet as a simple way to avoid religious prohibitions against such things as pork products or gelatin. Forbidden foods are referred to as “Haraam.”

- Muslim dietary regulation can affect patients’ use of medications, especially drugs that have pork origins or that contain gelatin or alcohol. The dietary prohibition against alcohol has occasionally raised questions about Muslims’ use of alcohol-based hand rubs in the hospital. Because hand rubs do not have an intoxicating effect and are used for life-saving hygiene, any concern should be addressed thoroughly and sensitively and perhaps with the input of an imam. An imam is a person who leads prayers in a mosque.

- The act of washing may require running water, either from a tap or poured from a pitcher. As a result, Muslim patients typically do not feel truly cleaned by a sponge bath. Many Muslims wash with running water before and after meals and also before prayers.

- Muslim prayers are conducted five times a day. Patients may desire to pray by kneeling and bending to the floor, but Islamic tradition recognizes circumstances when this is not medically advisable. If patients are disturbed by their inability to pray on the floor, advice should be encouraged from an imam. See Figure 18.13[32] for an image of Muslim men prostrate in prayer.

- Muslim patients may react to suffering with emotional reserve and may hesitate to express the need for pain management. Some may even refuse pain medication if they understand the experience of their pain to be spiritually enriching.

- There may be a request that amputated limbs be made available for burial. Details should be arranged through the patient’s/family’s funeral home.

- Muslim tradition generally discourages the withholding or withdrawing of life-sustaining therapy. However, because decisions on this subject involve the particular circumstances of the patient and the complexities of medical treatments, family members who are morally conflicted may wish to bring an experienced imam into their discussion with physicians.

- A family member may request to be present with a dying person, so as to be able to whisper a proclamation of faith in the patient’s ear right before death. (Similarly, a husband may request to be present at a birth to whisper a proclamation of faith in the ear of the newborn.)

- After a death, the family may request to wash the patient and to position their bed to face Mecca. The patient’s head should rest on a pillow.

- Burial is usually accomplished as soon as possible. Muslim families rarely allow for autopsy unless there is an order by a Medical Examiner. Some Muslims may consider organ donation, but the subject is open to great differences of opinion within Islamic circles.

- During the thirty-day month of Ramadan, Muslims refrain from food and drink from dawn until sundown. Physicians should explore with patients whether it is medically appropriate to fast while in the hospital. If so, investigate options for predawn meals, for providing patients with dates and spring water in the late afternoon (a traditional way to break the daily fast), and for delaying dinner until after sunset. While anyone who is ill is not obligated to fast, the Ramadan observance can be powerfully meaningful to patients if they can participate. The month of Ramadan shifts according to a lunar calendar, and when it occurs during the summertime, longer days can make the fast more physically stressful.[33]

Pentecostal Patients

- Pentecostal patients may pray exuberantly. Noise concerns in a hospital can sometimes present a problem in this regard, but simply shutting the door to the patient’s room can usually provide an adequate solution.

- Pentecostals may pray by “speaking in tongues,” expression of words that seem unintelligible to an individual hearer but holds very deep religious significance for worshippers.

- Patients or families may request that relatively large numbers of people be allowed in the patient’s room for prayer.

- Patients or families may express strong belief in miraculous healing.[34]

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Sociology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Sociology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology ↵

- “RELIGIONES.png” by Niusereset is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Sociology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Sociology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Sociology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Sociology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Sociology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology ↵

- “star-of-david-458372_960_720.jpg” by hurk is licensed under CC0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Sociology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology ↵

- “crucifix-4061847_960_720.jpg” by fz_3d is licensed under CC0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Sociology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Sociology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Sociology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology ↵

- “Amman_BW_29.JPG” by Berthold Werner is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Sociology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Sociology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Sociology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology ↵

- “Shiva_Bangalore.jpg” by Kalyan Kumar is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Sociology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology ↵

- This work is a derivative of Introduction to Sociology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology ↵

- “Four_Scenes_from_the_Life_of_the_Buddha_-_Enlightenment_-_Kushan_dynasty,_late_2nd_to_early_3rd_century_AD,_Gandhara,_schist_-_Freer_Gallery_of_Art_-_DSC05124.JPG” by Daderot is in the Public Domain, CC0 ↵

- “Vegetarian_meal_at_Buddhist_temple_(3810298969).jpg” by Andrea Schaffer is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- Ehman, J. (2012, May 8). Religious diversity: Practical points for healthcare providers. Penn Medicine: Pastoral Care and Education. https://www.uphs.upenn.edu/pastoral/resed/diversity_points.html ↵

- “SilverRosary.png” by Aprilwine is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Ehman, J. (2012, May 8). Religious diversity: Practical points for healthcare providers. Penn Medicine: Pastoral Care and Education. https://www.uphs.upenn.edu/pastoral/resed/diversity_points.html ↵

- “hindu-1588337_960_720.jpg” by gauravaroraji0 is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Ehman, J. (2012, May 8). Religious diversity: Practical points for healthcare providers. Penn Medicine: Pastoral Care and Education. https://www.uphs.upenn.edu/pastoral/resed/diversity_points.html ↵

- Ehman, J. (2012, May 8). Religious diversity: Practical points for healthcare providers. Penn Medicine: Pastoral Care and Education. https://www.uphs.upenn.edu/pastoral/resed/diversity_points.html ↵

- “Casamento_judeu1.jpg” by David Berkowitz is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- Ehman, J. (2012, May 8). Religious diversity: Practical points for healthcare providers. Penn Medicine: Pastoral Care and Education. https://www.uphs.upenn.edu/pastoral/resed/diversity_points.html ↵

- “Mosque.jpg” by Antonio Melina/Agência Brasil is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- Ehman, J. (2012, May 8). Religious diversity: Practical points for healthcare providers. Penn Medicine: Pastoral Care and Education. https://www.uphs.upenn.edu/pastoral/resed/diversity_points.html ↵

- Ehman, J. (2012, May 8). Religious diversity: Practical points for healthcare providers. Penn Medicine: Pastoral Care and Education. https://www.uphs.upenn.edu/pastoral/resed/diversity_points.html ↵