Scope of Practice

1.6 Legal Considerations & Ethics

Legal Considerations

As discussed earlier in this chapter, nurses can be reprimanded or have their licenses revoked for not appropriately following the Nurse Practice Act in the state they are practicing. Nurses can also be held legally liable for negligence, malpractice, or breach of patient confidentiality when providing patient care.

Negligence and Malpractice

Negligence is a “general term that denotes conduct lacking in due care, carelessness, and a deviation from the standard of care that a reasonable person would use in a particular set of circumstances.”[1] Malpractice is a more specific term that looks at a standard of care, as well as the professional status of the caregiver.” [2]

To prove negligence or malpractice, the following elements must be established in a court of law:

- Duty owed the patient

- Breach of duty owed the patient

- Foreseeability

- Causation

- Injury

- Damages[3]

To avoid being sued for negligence or malpractice, it is essential for nurses and nursing students to follow the scope and standards of practice care set forth by their state’s Nurse Practice Act; the American Nurses Association; and employer policies, procedures, and protocols to avoid the risk of losing their nursing license. Examples of nurses breach of duty that can be viewed as negligence include:[4]

- Failure to Assess: Nurses should assess for all potential nursing problems/diagnoses, not just those directly affected by the medical disease. For example, all patients should be assessed for fall risk and appropriate fall precautions implemented.

- Insufficient monitoring: Some conditions require frequent monitoring by the nurse, such as risk for falls, suicide risk, confusion, and self-injury.

- Failure to Communicate:

- Lack of documentation: A basic rule of thumb in a court of law is that if an assessment or action was not documented, it is considered not done. Nurses must document all assessments and interventions, in addition to the specific type of patient documentation called a nursing care plan.

- Lack of provider notification: Changes in patient condition should be urgently communicated to the health care provider based on patient status. Documentation of provider notification should include the date, time, and person notified and follow-up actions taken by the nurse.

- Failure to Follow Protocols: Agencies and states have rules for reporting certain behaviors or concerns. For example, a nurse is required to report suspicion of patient, child, or elder abuse based on data gathered during an assessment.

Patient Confidentiality

In addition to negligence and malpractice, patient confidentiality is a major legal consideration for nurses and nursing students. Patient confidentiality is the right of an individual to have personal, identifiable medical information, referred to as protected health information (PHI), kept private. This right is protected by federal regulations called the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). HIPAA was enacted in 1996 and was prompted by the need to ensure privacy and protection of personal health records and data in an environment of electronic medical records and third-party insurance payers. There are two main sections of HIPAA law, the Privacy Rule and the Security Rule. The Privacy Rule addresses the use and disclosure of individuals’ health information. The Security Rule sets national standards for protecting the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of electronically protected health information. HIPAA regulations extend beyond medical records and apply to patient information shared with others. Therefore, all types of patient information should only be shared with health care team members who are actively providing care to them.

How do HIPAA regulations affect you as a student nurse? You are required to adhere to HIPAA guidelines from the moment you begin to provide patient care. Nursing students may be disciplined or expelled by their nursing program for violating HIPAA. Nurses who violate HIPAA rules may be fired from their jobs or face lawsuits. See the following box for common types of HIPAA violations and ways to avoid them.

Common HIPAA Violations and Ways to Avoid Them[5]

- Gossiping in the hallways or otherwise talking about patients where other people can hear you. It is understandable that you will be excited about what is happening when you begin working with patients and your desire to discuss interesting things that occur. As a student, you will be able to discuss patient care in a confidential manner behind closed doors with your instructor. However, as a health care professional, do not talk about patients in the hallways, elevator, breakroom, or with others who are not directly involved with that patient’s care because it is too easy for others to overhear what you are saying.

- Mishandling medical records or leaving medical records unsecured. You can breach HIPAA rules by leaving your computer unlocked for anyone to access or by leaving written patient charts in unsecured locations. You should never share your password with anyone else. Make sure that computers are always locked with a password when you step away from them and paper charts are closed and secured in an area where unauthorized people don’t have easy access to them. NEVER take records from a facility or include a patient’s name on paperwork that leaves the facility.

- Illegally or unauthorized accessing of patient files. If someone you know, like a neighbor, coworker, or family member is admitted to the unit you are working on, do not access their medical record unless you are directly caring for them. Facilities have the capability of tracing everything you access within the electronic medical record and holding you accountable. This rule holds true for employees who previously cared for a patient as a student; once your shift is over as a student, you should no longer access that patient’s medical records.

- Sharing information with unauthorized people. Anytime you share medical information with anyone but the patient themselves, you must have written permission to do so. For instance, if a husband comes to you and wants to know his spouse’s lab results, you must have permission from his spouse before you can share that information with him. Just confirming or denying that a patient has been admitted to a unit or agency can be considered a breach of confidentiality.

- Information can generally be shared with the parents of children until they turn 18, although there are exceptions to this rule if the minor child seeks birth control, an abortion, or becomes pregnant. After a child turns 18, information can no longer be shared with the parent unless written permission is provided, even if the minor is living at home and/or the parents are paying for their insurance or health care. As a general rule, any time you are asked for patient information, check first to see if the patient has granted permission.

- Texting or e-mailing patient information on an unencrypted device. Only use properly encrypted devices that have been approved by your health care facility for e-mailing or faxing protected patient information. Also, ensure that the information is being sent to the correct person, address, or phone number.

- Sharing information on social media. Never post anything on social media that has anything to do with your patients, the facility where you are working or have clinical, or even how your day went at the agency. Nurses and other professionals have been fired for violating HIPAA rules on social media.[6],[7],[8]

Social Media Guidelines

Nursing students, nurses, and other health care team members must use extreme caution when posting to Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, and other social media sites. Information related to patients, patient care, and/or health care agencies should never be posted on social media; health care team members who violate this guideline can lose their jobs and may face legal action and students can be disciplined or expelled from their nursing program. Be aware that even if you think you are posting in a private group, the information can become public.

The American Nurses Association (ANA) has established the following principles for nurses using social media:[9]

- Nurses must not transmit or place online individually identifiable patient information.

- Nurses must observe ethically prescribed professional patient-nurse boundaries.

- Nurses should understand that patients, colleagues, organizations, and employers may view postings.

- Nurses should take advantage of privacy settings and seek to separate personal and professional information online.

- Nurses should bring content that could harm a patient’s privacy, rights, or welfare to the attention of appropriate authorities.

- Nurses should participate in developing organizational policies governing online conduct.

In addition to these principles, the ANA has also provided these tips for nurses and nursing students using social media:[10]

- Remember that standards of professionalism are the same online as in any other circumstance.

- Do not share or post information or photos gained through the nurse-patient relationship.

- Maintain professional boundaries in the use of electronic media. Online contact with patients blurs this boundary.

- Do not make disparaging remarks about patients, employers, or coworkers, even if they are not identified.

- Do not take photos or videos of patients on personal devices, including cell phones.

- Promptly report a breach of confidentiality or privacy.

Read more about the ANA’s Social Media Principles.

Code of Ethics

In addition to legal considerations, there are also several ethical guidelines for nursing care.

There is a difference between morality, ethical principles, and a code of ethics. Morality refers to “personal values, character, or conduct of individuals within communities and societies.”[11] An ethical principle is a general guide, basic truth, or assumption that can be used with clinical judgment to determine a course of action. Four common ethical principles are beneficence (do good), nonmaleficence (do no harm), autonomy (control by the individual), and justice (fairness). A code of ethics is set for a profession and makes their primary obligations, values, and ideals explicit.

The American Nursing Association (ANA) guides nursing practice with the Code of Ethics for Nurses.[12] This code provides a framework for ethical nursing care and a guide for decision-making. The Code of Ethics for Nurses serves the following purposes:

- It is a succinct statement of the ethical values, obligations, duties, and professional ideals of nurses individually and collectively.

- It is the profession’s nonnegotiable ethical standard.

- It is an expression of nursing’s own understanding of its commitment to society.[13]

The ANA Code of Ethics contains nine provisions. See a brief description of each provision in the following box.

Provisions of the ANA Code of Ethics[14]

The nine provisions of the ANA Code of Ethics are briefly described below. The full code is available to read for free at Nursingworld.org.

Provision 1: The nurse practices with compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person.

Provision 2: The nurse’s primary commitment is to the patient, whether an individual, family, group, community, or population.

Provision 3: The nurse promotes, advocates for, and protects the rights, health, and safety of the patient.

Provision 4: The nurse has authority, accountability, and responsibility for nursing practice; makes decisions; and takes action consistent with the obligation to promote health and to provide optimal care.

Provision 5: The nurse owes the same duties to self as to others, including the responsibility to promote health and safety, preserve wholeness of character and integrity, maintain competence, and continue personal and professional growth.

Provision 6: The nurse, through individual and collective effort, establishes, maintains, and improves the ethical environment of the work setting and conditions of employment that are conducive to safe, quality health care.

Provision 7: The nurse, in all roles and settings, advances the profession through research and scholarly inquiry, professional standards development, and the generation of both nursing and health policy.

Provision 8: The nurse collaborates with other health professionals and the public to protect human rights, promote health diplomacy, and reduce health disparities.

Provision 9: The profession of nursing, collectively through its professional organizations, must articulate nursing values, maintain the integrity of the profession, and integrate principles of social justice into nursing and health policy.

The ANA Center for Ethics and Human Rights

In addition to publishing the Code of Ethics, the ANA Center for Ethics and Human Rights was established to help nurses navigate ethical and value conflicts and life-and-death decisions, many of which are common to everyday practice.

Check your knowledge with the following questions:

- Missouri Department of Health & Senior Services. (n.d.). Negligence and malpractice. https://health.mo.gov/living/lpha/phnursing/negligence.php#:~:text=Negligence%20is%3A,a%20particular%20set%20of%20circumstances. ↵

- Missouri Department of Health & Senior Services. (n.d.). Negligence and malpractice. https://health.mo.gov/living/lpha/phnursing/negligence.php#:~:text=Negligence%20is%3A,a%20particular%20set%20of%20circumstances. ↵

- Missouri Department of Health & Senior Services. (n.d.). Negligence and malpractice. https://health.mo.gov/living/lpha/phnursing/negligence.php#:~:text=Negligence%20is%3A,a%20particular%20set%20of%20circumstances. ↵

- Vera, M. (2020). Nursing care plan (NCP): Ultimate guide and database. https://nurseslabs.com/nursing-care-plans/#:~:text=Collaborative%20interventions%20are%20actions%20that,to%20gain%20their%20professional%20viewpoint. ↵

- Patterson, A. (2018, July 3). Most common HIPAA violations with examples. Inspired eLearning. https://inspiredelearning.com/blog/hipaa-violation-examples/ ↵

- Karimi, H., & Masoudi Alavi, N. (2015). Florence Nightingale: The mother of nursing. Nursing and Midwifery Studies, 4(2), e29475. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4557413/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.). About ANA. https://www.nursingworld.org/ana/about-ana/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.). Scope of practice. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/scope-of-practice/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.). Social media. https://www.nursingworld.org/social/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.). Social media. https://www.nursingworld.org/social/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. American Nurses Association. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/ethics/code-of-ethics-for-nurses/coe-view-only/ ↵

Providing culturally responsive care integrates an individual’s cultural beliefs into their health care. Begin by conveying cultural sensitivity to patients and their family members with these suggestions:[1]

- Set the stage by introducing yourself by name and role when meeting the patient and their family for the first time. Until you know differently, address the patient formally by using their title and last name. Ask the patient how they wish to be addressed and record this in the patient’s chart. Respectfully acknowledge any family members and visitors at the patient’s bedside.

- Begin by standing or sitting at least arm’s length from the patient.

- Observe the patient and family members in regards to eye contact, space orientation, touch, and other nonverbal communication behaviors and follow their lead.

- Make note of the language the patient prefers to use and record this in the patient’s chart. If English is not the patient’s primary language, determine if a medical interpreter is required before proceeding with interview questions. See the box below for guidelines in using a medical interpreter.

- Use inclusive language that is culturally sensitive and appropriate. For example, do not refer to someone as “wheelchair bound”; instead say “a person who uses a wheelchair.” [2]

- Be open and honest about the extent of your knowledge of their culture. It is acceptable to politely ask questions about their beliefs and seek clarification to avoid misunderstandings.

- Adopt a nonjudgmental approach and show respect for the patient’s cultural beliefs, values, and practices. It is possible that you may not agree with a patient’s cultural expressions, but it is imperative that the patient’s rights are upheld. As long as the expressions are not unsafe for the patient or others, the nurse should attempt to integrate them into their care.

- Assure the patient that their cultural considerations are a priority their care.

Guidelines for Using a Medical Interpreter[3]

When caring for a patient whose primary language is not English and they have a limited ability to speak, read, write, or understand the English language, seek the services of a trained medical interpreter. Health care facilities are mandated by The Joint Commission to provide qualified medical interpreters. Use of a trained medical interpreter is linked to fewer communication errors, shorter hospital stays, reduced 30-day readmission rates, and improved patient satisfaction.

Refrain from asking a family member to act as an interpreter. The patient may withhold sensitive information from them, or family members may possibly edit or change the information provided. Unfamiliarity with medical terminology can also cause misunderstanding and errors.

Medical interpreters may be on-site or available by videoconferencing or telephone. The nurse should also consider coordinating patient and family member conversations with other health care team members to streamline communication, while being aware of cultural implications such who can discuss what health care topics and who makes the decisions. When possible, obtain a medical interpreter of the same gender as the patient to prevent potential embarrassment if a sensitive matter is being discussed.

Guidelines for working with a medical interpreter:

- Allow extra time for the interview or conversation with the patient.

- Whenever possible, meet with the interpreter beforehand to provide background.

- Document the name of the medical interpreter in the progress note.

- Always face and address the patient directly, using a normal tone of voice. Do not direct questions or conversation to the interpreter.

- Speak in the first person (using “I”).

- Avoid using idioms, such as, “Are you feeling under the weather today?” Avoid abbreviations, slang, jokes, and jargon.

- Speak in short paragraphs or sentences. Ask only one question at a time. Allow sufficient time for the interpreter to finish interpreting before beginning another statement or topic.

- Ask the patient to repeat any instructions and explanations given to verify that they understood.

After establishing a culturally sensitive environment and performing a cultural assessment, nurses and nursing students can continue to promote culturally responsive care. Culturally responsive care includes creating a culturally safe environment, using cultural negotiation, and considering the impact of culture on patients’ time orientation, space orientation, eye contact, and food choices.

Culturally Safe Environment

A primary responsibility of the nurse is to ensure the environment is culturally safe for the patient. A culturally safe environment is a safe space for patients to interact with the nurse, without judgment or discrimination, where the patient is free to express their cultural beliefs, values, and identity. This responsibility belongs to both the individual nurse and also to the larger health care organization.

Cultural Negotiation

Many aspects of nursing care are influenced by the patient’s cultural beliefs, as well as the beliefs of the health care culture. For example, the health care culture in the United States places great importance on punctuality for medical appointments, yet a patient may belong to a culture that views “being on time” as relative. In some cultures, time is determined simply by whether it is day or night or time to wake up, eat, or sleep. Making allowances or accommodations for these aspects of a patient’s culture is instrumental in fostering the nurse-patient relationship. This accommodation is referred to as cultural negotiation. See Figure 3.6[4] for an image illustrating cultural negotiation. During cultural negotiation, both the patient and nurse seek a mutually acceptable way to deal with competing interests of nursing care, prescribed medical care, and the patient’s cultural needs. Cultural negotiation is reciprocal and collaborative. When a patient’s cultural needs do not significantly or adversely affect their treatment plan, their cultural needs should be accommodated when feasible.

As an example, think about the previous example of a patient for whom a fixed schedule is at odds with their cultural views. Instead of teaching the patient to take a daily medication at a scheduled time, the nurse could explain that the patient should take the medication every day when he gets up. Another example of cultural negotiation is illustrated by a scenario in which the nurse is preparing a patient for a surgical procedure. As the nurse goes over the preoperative checklist, the nurse asks the patient to remove her head covering (hijab). The nurse is aware that personal items should be removed before surgery; however, the patient wishes to keep on the hijab. As an act of cultural negotiation and respect for the patient’s cultural beliefs, the nurse makes arrangements with the surgical team to keep the patient’s hijab in place for the surgical procedure and covering the patient’s hijab with a surgical cap.

Decision-Making

Health care culture in the United States mirrors cultural norms of the country, with an emphasis on individuality, personal freedom, and self-determination. This perspective may conflict with a patient whose cultural background values group decision-making and decisions made to benefit the group, not necessarily the individual. As an example, in the 2019 film The Farewell, a Chinese-American family decides to not tell the family matriarch she is dying of cancer and only has a few months left to live. The family keeps this secret from the woman in the belief that the family should bear the emotional burden of this knowledge, which is a collectivistic viewpoint in contrast to American individualistic viewpoint.

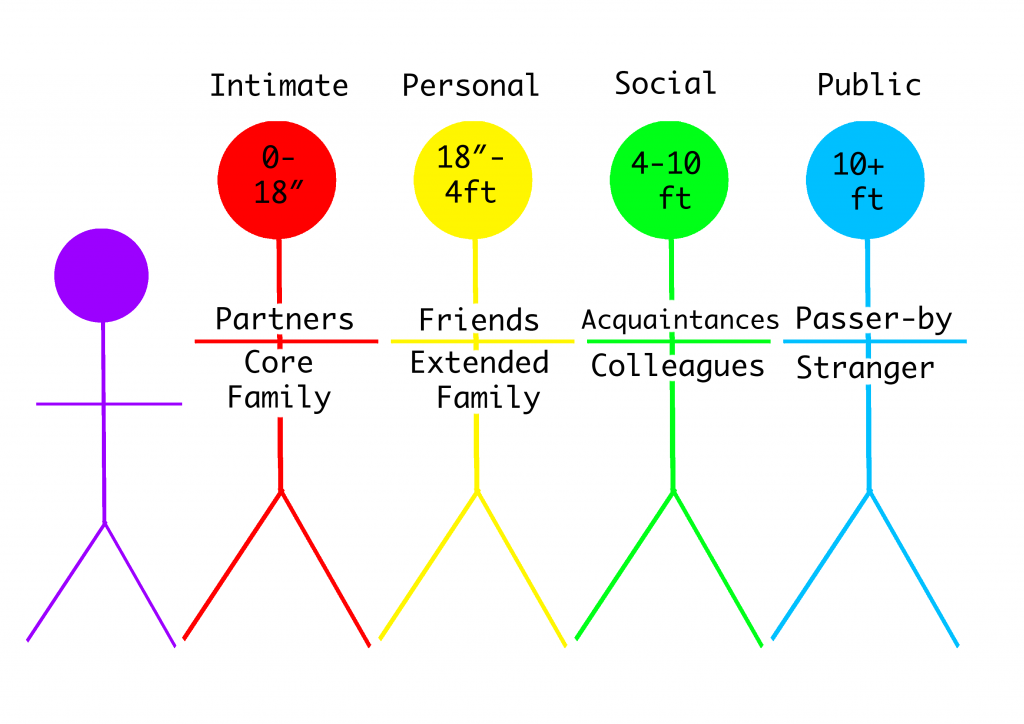

Space Orientation

The amount of space that a person surrounds themselves with to feel comfortable is influenced by culture. (Read more about space orientation in the "Communication" chapter.) See Figure 3.7[5] for an image illustrating space orientation. For example, for some people, it would feel awkward to stand four inches away from another person while holding a social conversation, but for others a small personal space is expected when conversing with another.[6]There are times when a nurse must enter a patient’s intimate or personal space, which can cause emotional distress for some patients. The nurse should always ask for permission before entering a patient’s personal space and explain why and what is about to happen.

Patients may also be concerned about their modesty or being exposed. A patient may deal with the violation of their space by removing themselves from the situation, pulling away, or closing their eyes. The nurse should recognize these cues for what they are, an expression of cultural preference, and allow the patient to assume a position or distance that is comfortable for them.

Similar to cultural influences on personal space, touch is also culturally determined. This has implications for nurses because it may be inappropriate for a male nurse to provide care for a female patient and vice versa. In some cultures, it is also considered rude to touch a person’s head without permission.

Eye Contact

Eye contact is also a culturally mediated behavior. See Figure 3.8[7] for an image of eye contact. In the United States, direct eye contact is valued when communicating with others, but in some cultures, direct eye contact is interpreted as being rude or bold. Rather than making direct eye contact, a patient may avert their eyes or look down at the floor to show deference and respect to the person who is speaking. The nurse should notice these cultural cues from the patient and mirror the patient’s behaviors when possible.

Food Choices

Culture plays a meaningful role in the dietary practices and food choices of many people. Food is used to celebrate life events and holidays. Most cultures have staple foods, such as bread, pasta, or rice and particular ways of preparing foods. See Figure 3.9[8] for an image of various food choices. Special foods are prepared to heal and to cure or to demonstrate kinship, caring, and love. For example, in the United States, chicken noodle soup is often prepared and provided to family members who are ill.

Conversely, certain foods and beverages (such as meat and alcohol) are forbidden in some cultures. Nurses should accommodate or negotiate dietary requests of their patients, knowing that food holds such an important meaning to many people.

Summary

In summary, there are several steps in the journey of becoming a culturally competent nurse with cultural humility who provides culturally responsive care to patients. As you continue in your journey of developing cultural competency, keep the summarized points in the following box in mind.

Summary of Developing Cultural Competency

- Cultural competence is an ongoing process for nurses and takes dedication, time, and practice to develop.

- Pursuing the goal of cultural competence in nursing and other health care disciplines is a key strategy in reducing health care disparities.

- Culturally competent nurses recognize that culture functions as a source of values and comfort for patients, their families, and communities.

- Culturally competent nurses intentionally provide patient-centered care with sensitivity and respect for culturally diverse populations.

- Misunderstandings, prejudices, and biases on the part of the health care provider interfere with the patient’s health outcomes.

- Culturally competent nurses negotiate care with a patient so that is congruent with the patient’s cultural beliefs and values.

- Nurses should examine their own biases, ethnocentric views, and prejudices so as not to interfere with the patient’s care.

- Nurses who respect and understand the cultural values and beliefs of their patients are more likely to develop positive, trusting relationships with their patients.