Scope of Practice

1.5 Nursing Education and the NCLEX

Nursing Education and the NCLEX

Everyone who wants to become a nurse has a story to tell about why they want to enter the nursing profession. What is your story? Perhaps it has been a lifelong dream to become a Life Flight nurse, or maybe you became interested after watching a nurse help you or a family member through the birth of a baby, heal from a challenging illness, or assist a loved one at the end of life. Whatever the reason, everyone who wants to become a nurse must do two things: graduate from a state-approved nursing program and pass the National Council Licensure Exam (known as the NCLEX).

Nursing Programs

There are several types of nursing programs you can attend to become a nurse. If your goal is to become a Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN), you must successfully complete a one-year nursing program, pass the NCLEX-PN exam, and apply to your state board of nursing to receive a LPN license.

If you want to become a Registered Nurse, you can obtain either a two-year associate degree (ADN) or a four-year baccalaureate of science in nursing degree (BSN). Associate degree nursing graduates often enroll into a baccalaureate or higher degree program after they graduate. Many hospitals hire ADN nurses on a condition they complete their BSN within a specific time frame. A BSN is required for military nursing, case management, public health nursing, and school-based nursing services. Another lesser-known option to become an RN is to complete a three-year hospital-based diploma program, which was historically the most common way to become a nurse. Diploma programs have slowly been replaced by college degrees, and now only nine states offer this option.[1] After completing a diploma program, associate degree, or baccalaureate degree, nursing graduates must successfully pass the NCLEX-RN to apply for a registered nursing license from their state’s Board of Nursing.

NCLEX

Nursing graduates must successfully pass the National Council Licensure Examination (NCLEX) to receive a nursing license. Registered nurses must successfully pass the NCLEX-RN exam, and Licensed Practical Nurses (LPNs) or Licensed Vocational Nurses (LVNs) must pass the NCLEX-PN exam.

The NCLEX-PN and NCLEX-RN are online, adaptive tests taken at a specialized testing center. The NCLEX tests knowledge, skills, and abilities essential to the safe and effective practice of nursing at the entry level. NCLEX exams are continually reviewed and updated based on surveys of newly graduated nurses every three years.

Both the NCLEX-RN and the NCLEX-PN are variable length tests that adapt as you answer the test items. The NCLEX-RN examination can be anywhere from 75 to 265 items, depending on how quickly you are able to demonstrate your proficiency. Of these items, 15 are unscored test items. The time limit for this examination is six hours. The NCLEX-PN examination can be anywhere from 85 to 205 items. Of these items, 25 are unscored items. The time limit for this examination is five hours.[2]

You will have Kaplan Nursing Resources for formulating a study plan starting with this course and continuing with this resource in your Nicolet College Nursing Education journey! Please sign in to your account to get started and follow the Brightspace assignments to participate in your plan. http://https://atom.kaptest.com/studyplan/gettingStarted

In 2023, the Next Generation NCLEX (NGN) is anticipated to go into effect. Examination questions on the NGN will use the new Clinical Judgment Measurement Model as a framework to measure prelicensure nursing graduates’ clinical judgment and decision-making. The critical thinking model called the “Nursing Process” (discussed in Chapter 4 of this book) will continue to underlie the NGN, but candidates will notice new terminology used to assess their decision-making. For example, candidates may be asked to “recognize cues,” “analyze cues,” “create a hypothesis,” “prioritize hypotheses,” “generate solutions,” “take actions,” or “evaluate outcomes.”[3] For this reason, many of the case studies and learning activities included in this book will use similar terminology as the NGN.

There will also be new types of examination questions on the NGN, including case studies, enhanced hot spots, drag and drop ordering of responses, multiple responses, and embedded answer choices within paragraphs of text. View sample NGN questions in the following hyperlink. NCSBN’s rationale for including these types of questions is to “measure the nursing clinical judgment and decision-making ability of prospective entry-level nurses to protect the public’s health and welfare by assuring that safe and competent nursing care is provided by licensed nurses.”[4] Similar questions have been incorporated into learning activities throughout this textbook.

Use the hyperlinks below to read more information about the NCLEX and the Next Generation NCLEX.

Read more information about the NCLEX & Test Plans.

Review sample Next Generation NCLEX questions at https://www.ncsbn.org/NGN-Sample-Questions.pdf.

Nurse Licensure Compact

The Nurse Licensure Compact (NLC) allows a nurse to have one multistate nursing license with the ability to practice in their home state, as well as in other compact states. As of 2020, 33 states have implemented NLC legislation.

Read additional details about the Nurse Licensure Compact.

Advanced Nursing Degrees

After obtaining an RN license, nurses can receive advanced degrees to expand their opportunities in the nursing profession.

Master’s Degree in Nursing

A Master’s of Science in Nursing Degree (MSN) requires additional credits and years of schooling beyond the BSN. There are a variety of potential focuses in this degree, including Nurse Educator and Advanced Practice Nurse (APRN). Certifications associated with an MSN degree are Certified Nurse Educator (CNE), Nurse Practitioner (NP), Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS), Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist (CRNA), and Certified Nurse Midwife (CNM). Certifications require the successful completion of a certification exam, as well as continuing education requirements to maintain the certification. Scope of practice for advanced practice nursing roles is defined by each state’s Nurse Practice Act.

Doctoral Degrees in Nursing

Doctoral nursing degrees include the Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing (PhD) and the Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP). PhD-prepared nurses complete doctoral work that is focused on research. They often teach in a university setting or environment to conduct research. DNP-prepared nurses complete doctoral work that is focused on clinical nursing practice. They typically have work roles in advanced nursing practice, clinical leadership, or academic settings.

Lifelong Learning

No matter what nursing role or level of nursing education you choose, nursing practice changes rapidly and is constantly updated with new evidence-based practices. Nurses must commit to lifelong learning to continue to provide safe, quality care to their patients. Many states require continuing education credits to renew RN licenses, whereas others rely on health care organizations to set education standards and ongoing educational requirements.

Now that we have discussed nursing roles and education, let’s review legal and ethical considerations in nursing.

- NCSBN. (2019). 2018 NCLEX examination statistics 77. https://www.ncsbn.org/2018_NCLEXExamStats.pdf ↵

- NCSBN. (2019). NCLEX & Other Exams. https://www.ncsbn.org/nclex.htm ↵

- NCSBN. (2021). NCSBN Next Generation NCLEX Project. https://www.ncsbn.org/next-generation-nclex.htm ↵

- NCSBN. (2021). NCSBN Next Generation NCLEX Project. https://www.ncsbn.org/next-generation-nclex.htm ↵

Let’s begin the journey of developing cultural competency by exploring basic concepts related to culture.

Culture and Subculture

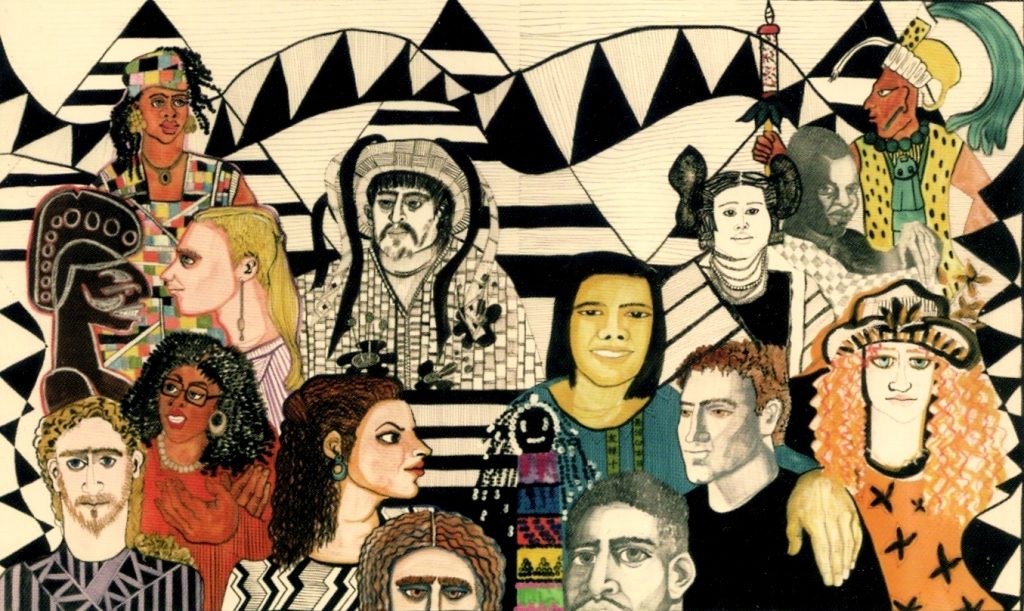

Culture is a set of beliefs, attitudes, and practices shared by a group of people or community that is accepted, followed, and passed down to other members of the group. The word “culture” may at times be interchanged with terms such as ethnicity, nationality, or race. See Figure 3.1[1] for an illustration depicting culture by various nationalities. Cultural beliefs and practices bind group or community members together and help form a cohesive identity.[2],[3] Culture has an enduring influence on a person’s view of the world, expressed through language and communication patterns, family connections and kinship, religion, cuisine, dress, and other customs and rituals.[4] Culture is not static but is dynamic and ever-changing; it changes as members come into contact with beliefs from other cultures. For example, sushi is a traditional Asian dish that has become popular in America in recent years.

Nurses and other health care team members are impacted by their own personal cultural beliefs. For example, a commonly held belief in American health care is the importance of timeliness; medications are administered at specifically scheduled times, and appearing for appointments on time is considered crucial.

Most cultural beliefs are a combination of beliefs, values, and habits that have been passed down through family members and authority figures. The first step in developing cultural competence is to become aware of your own cultural beliefs, attitudes, and practices.

Nurses should also be aware of subcultures. A subculture is a smaller group of people within a culture, often based on a person’s occupation, hobbies, interests, or place of origin. People belonging to a subculture may identify with some, but not all, aspects of their larger “parent” culture. Members of the subculture share beliefs and commonalities that set them apart and do not always conform with those of the larger culture. See Table 3.2a for examples of subcultures.

Table 3.2a Examples of Subcultures

| Age/Generation | Baby Boomers, Millennials, Gen Z |

|---|---|

| Occupation | Truck Driver, Computer Scientist, Nurse |

| Hobbies/Interests | Birdwatchers, Gamers, Foodies, Skateboarders |

| Religion | Hinduism, Baptist, Islam |

| Gender | Male, Female, Nonbinary, Two-Spirit |

| Geography | Rural, Urban, Southern, Midwestern |

Culture is much more than a person’s nationality or ethnicity. Culture can be expressed in a multitude of ways, including the following:

- Language(s) spoken

- Religion and spiritual beliefs

- Gender identity

- Socioeconomic status

- Age

- Sexual orientation

- Geography

- Educational background

- Life experiences

- Living situation

- Employment status

- Immigration status

- Ability/Disability

People typically belong to more than one culture simultaneously. These cultures overlap, intersect, and are woven together to create a person’s cultural identity. In other words, the many ways in which a person expresses their cultural identity are not separated, but are closely intertwined, referred to as intersectionality.

Assimilation

Assimilation is the process of adopting or conforming to the practices, habits, and norms of a cultural group. As a result, the person gradually takes on a new cultural identity and may lose their original identity in the process.[5] An example of assimilation is a newly graduated nurse, who after several months of orientation on the hospital unit, offers assistance to a colleague who is busy. The new nurse has developed self-confidence in the role and has developed an understanding that helping others is a norm for the nurses on that unit.

Assimilation is not always voluntary, however, and may become a source of distress. There are historic examples of involuntary assimilation in many countries. For example, in the past, authorities in the United States and Canadian governments required indigenous children to attend boarding schools, separated them from their families, and punished them for speaking their native language.[6],[7]

Cultural Values and Beliefs

Culture provides an important source of values and comfort for patients, families, and communities. Think of culture as a thread that is woven through a person’s world and impacts one’s choices, perspectives, and way of life. It plays a role in all of a person’s life events and threads its way through the development of one’s self-concept, sexuality, and spirituality. It affects lifelong nutritional habits, as well as coping strategies with death and dying.

Culture influences how a patient interprets “good” health, as well as their perspectives on illness and the causes of illness. The manner in which pain is expressed is also shaped by a person’s culture. See Table 3.2b for additional examples of how a person’s culture impacts common values and beliefs regarding family patterns, communication patterns, space orientation, time orientation, and nutritional patterns. As you read Table 3.2b, take a moment to reflect on your own cultural background and your personally held beliefs for each of these concepts.

Table 3.2b Cultural Concepts

| Cultural Concepts | Examples of Culturally Influenced Values and Beliefs |

|---|---|

| Family Patterns | Family size

Views on contraception Roles of family members Naming customs Value placed on elders and children Discipline/upbringing of children Rites of passage End-of-life care |

| Communication Patterns | Eye contact

Touch Use of silence or humor Intonation, vocabulary, grammatical structure Topics considered personal (i.e., difficult to discuss) Greeting customs (handshakes, hugs) |

| Space Orientation | Personal distance and intimate space |

| Time Orientation | Focus on the past, present, or future

Importance of following a routine or schedule Arrival on time for appointments |

| Nutritional Patterns | Common meal choices

Foods to avoid Foods to heal or treat disease Religious practices (e.g., fasting, dietary restrictions) Foods to celebrate life events and holidays |

A person’s culture can also affect encounters with health care providers in other ways, such as the following:

- Level of family involvement in care

- Timing for seeking care

- Acceptance of treatment (as preventative measure or for an actual health problem)

- The accepted decision-maker (i.e., the patient or other family members)

- Use of home or folk remedies

- Seeking advice or treatment from nontraditional providers

- Acceptance of a caregiver of the opposite gender

Cultural Diversity and Cultural Humility

Cultural diversity is a term used to describe cultural differences among people. See Figure 3.2[8] for artwork depicting diversity. While it is useful to be aware of specific traits of a culture or subculture, it is just as important to understand that each individual is unique and there are always variations in beliefs among individuals within a culture. Nurses should, therefore, refrain from making assumptions about the values and beliefs of members of specific cultural groups.[9] Instead, a better approach is recognizing that culture is not a static, uniform characteristic but instead realizing there is diversity within every culture and in every person. The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines cultural humility as, "A humble and respectful attitude toward individuals of other cultures that pushes one to challenge their own cultural biases, realize they cannot possibly know everything about other cultures, and approach learning about other cultures as a lifelong goal and process."[10]

Current demographics in the United States reveal that the population is predominantly white. People who were born in another country, but now live in the United States, comprise approximately 14% of the nation’s total population. However, these demographics are rapidly changing. The United States Census Bureau projects that more than 50 percent of Americans will belong to a minority group by 2060. With an increasingly diverse population to care for, it is imperative for nurses to integrate culturally responsive care into their nursing practice.[11],[12] Creative a culturally responsive environment is discussed in a later subsection of this chapter.

Concepts Related to Culture

There are additional concepts related to culture that can impact a nurse’s ability to provide culturally responsive care, including stereotyping, ethnocentrism, discrimination, prejudice, and bias. See Table 3.2c for definitions and examples of these concepts.

Table 3.2c Concepts Related to Culture

| Concepts | Definitions | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Stereotyping | The assumption that a person has the attributes, traits, beliefs, and values of a cultural group because they are a member of that group. | The nurse teaches the daughter of an older patient how to make online doctor appointments, assuming that the older patient does not understand how to use a computer. |

| Ethnocentrism | The belief that one’s culture (or race, ethnicity, or country) is better and preferable than another’s. | The nurse disparages the patient’s use of nontraditional medicine and tells the patient that traditional treatments are superior. |

| Discrimination | The unfair and different treatment of another person or group, denying them opportunities and rights to participate fully in society. | A nurse manager refuses to hire a candidate for a nursing position because she is pregnant. |

| Prejudice | A prejudgment or preconceived idea, often unfavorable, about a person or group of people. | The nurse withholds pain medication from a patient with a history of opioid addiction. |

| Bias | An attitude, opinion, or inclination (positive or negative) towards a group or members of a group. Bias can be a conscious attitude (explicit) or an unconscious attitude where the person is not aware of their bias (implicit). | A patient does not want the nurse to care for them because the nurse has a tattoo. |

Race is a socially constructed idea because there are no true genetically- or biologically-distinct races. Humans are not biologically different from each other. Racism presumes that races are distinct from one another, and there is a hierarchy to race, implying that races are unequal. Ernest Grant, president of the American Nurses Association (ANA), recently declared that nurses are obligated “to speak up against racism, discrimination, and injustice. This is non-negotiable.”[13] As frontline health care providers, nurses have an obligation to recognize the impact of racism on their patients and the communities they serve.[14]

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Culture can exert a powerful influence on a person’s sexual orientation and gender expression. Sexual orientation refers to a person’s physical and emotional interest or desire for others. Sexual orientation is on a continuum and is manifested in one’s self-identity and behaviors.[15] The acronym LGBTQ stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or questioning in reference to sexual orientation. (A “+” is sometimes added after LGBTQ to capture additional orientations). See Figure 3.3[16] for an image of participants in a LGBTQ rally in Dublin. Historically, individuals within the LGBTQ community have experienced discrimination and prejudice from health care providers and avoided or delayed health care due to these negative experiences. Despite increased recognition of this group of people in recent years, members of the LGBTQ community continue to experience significant health disparities. Persistent cultural bias and stigmatization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBTQ) people have also been shown to contribute to higher rates of substance abuse and suicide rates in this population.[17],[18],[19]

Gender identity refers to a person’s inner sensibility that they are a man, a woman, or perhaps neither. Cisgender is the term used to describe a person whose identity matches their sex assigned at birth.[20] To the extent that a person’s gender identity does not conform with the sex assigned to them at birth, they may identify as transgender or as gender nonbinary. Transgender people, like cisgender people, “may be sexually oriented toward men, women, both sexes, or neither sex.”[21] Gender expression refers to a person’s outward demonstration of gender in relation to societal norms, such as in style of dress, hairstyle, or other mannerisms.[22]Sharing pronouns as part of a basic introduction to a patient can assist a transgender patient to feel secure sharing their pronouns in a health care setting. Asking a patient for their pronoun (he, she, they, ze, etc.) is considered part of a nursing assessment.

Related Ethical Considerations

Justice, a principle and moral obligation to act on the basis of equality and equity, is a standard linked to fairness for all in society.[23] The ANA states this obligation guarantees not only basic rights (respect, human dignity, autonomy, security, and safety) but also fairness in all operations of societal structures. This includes care being delivered with fairness, rightness, correctness, unbiasedness, and inclusiveness while being based on well-founded reason and evidence.[24]

Social justice is related to respect, equity, and inclusion. The ANA defines social justice as equal rights, equal treatment, and equitable opportunities for all.[25] The ANA further states, "Nurses need to model the profession's commitment to social justice and health through actions and advocacy to address the social determinants of health and promote well-being in all settings within society."[26] Social determinants of health are nonmedical factors that influence health outcomes, including conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider sets of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.[27] Health outcomes impacted by social determinants of health are referred to as health disparities. Health disparities are further discussed in a subsection later in this chapter.

Despite decades of promoting cultural competent care and the Patient's Bill of Rights, disparities in health care continue. Vulnerable populations continue to experience increased prevalence and burden of diseases, as well as problems accessing quality health care. In 2003 the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, sharing evidence that “bias, prejudice, and stereotyping on the part of health care providers may contribute to differences in care.”[28] The health care system in the United States was shaped by the values and beliefs of mainstream white culture and originally designed to primarily serve English-speaking patients with financial resources.[29] In addition, most health care professionals in the United States are members of the white culture and medical treatments tend to arise from that perspective.[30],[31]

The term health disparities describes the differences in health outcomes that result from social determinants of health. Social determinants of health are conditions in the environment where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes. Resources that enhance quality of life can have a significant influence on population health outcomes. Examples of resources include safe and affordable housing, access to education, public safety, availability of healthy foods, local emergency/health services, and environments free of life-threatening toxins.[32]

Vulnerable populations experience increased prevalence and burden of diseases, as well as problems accessing quality health care because of social determinants of health. Health disparities negatively impact groups of people based on their ethnicity, gender, age, mental health, disability, sexual orientation, gender identity, socioeconomic status, geographic location, or other characteristics historically linked to discrimination or exclusion.[33] A related term is health care disparity that refers to differences in access to health care and insurance coverage. Health disparities and health care disparities can lead to decreased quality of life, increased personal costs, and lower life expectancy. More broadly, these disparities also translate to greater societal costs, such as the financial burden of uncontrolled chronic illnesses.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) releases an annual National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report that provides a comprehensive overview of the quality of health care received by the general U.S. population and disparities in care experienced by different racial and socioeconomic groups. Quality is described in terms of patient safety, person-centered care, care coordination, effective treatment, healthy living, and care affordability.[34] Although access to health care and quality have improved since 2000 in the wake of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the 2019 report shows continued disparities, especially for poor and uninsured populations:

- For about 40% of quality measures, Blacks, African Americans, and Alaska Natives received worse care than Whites. For more than one third of quality measures, Hispanics received worse care than Whites.

- For nearly a quarter of quality measures, residents of large metropolitan areas received worse care than residents of suburban areas. For one third of quality measures, residents of rural areas received worse care than residents of suburban areas.[35]

There are several initiatives and agencies designed to combat the problem of health disparities in the United States. See Table 3.5 for a list of hyperlinks to available resources to combat health disparities.

Table 3.5 Resources to Combat Health Disparities

| AHRQ publishes the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report, a report on measures related to access to care, affordable care, care coordination, effective treatment, healthy living, patient safety, and person-centered care. | |

| A new Healthy People initiative is launched every ten years. The initiative guides national health promotion and disease prevention efforts to improve the health of the nation. | |

| The mission of the Office of Minority Health is to improve the health of minority populations and to act as a resource for health care providers. The Office of Minority Health has published National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health and Health Care (CLAS). | |

|

Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health Across the United States (REACH-US) |

This initiative, overseen by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), seeks to remove barriers to health linked to race or ethnicity, education, income, location, or other social factors. |

|

National Partnership for Action to End Health Disparities (NPA) |

The mission of the NPA is to raise awareness and increase the effectiveness of programs targeting health disparities. |

| RWJF is a philanthropic organization with the goal of identifying the root causes of health disparities and removing barriers to improve health outcomes. | |

| The nonprofit Sullivan Alliance was formed to increase the numbers of ethnic and racial minorities within the health professions to raise awareness about health disparities and to develop partnerships between academia and the health professions. | |

|

Transcultural Nursing Society – Many Cultures One World (TCNS) |

The mission of TCNS is to improve the quality of culturally congruent and equitable care for people worldwide by ensuring cultural competence in nursing practice, scholarship, education, research, and administration. |

See the following box for an example of nurses addressing a community health care disparity during the water crisis in Flint, Michigan.

Nurses Addressing the Flint Michigan Water Crisis[36]

In 2014 the water system in Flint, Michigan, was discovered to be contaminated with lead. The city’s children were found to have perilously elevated lead levels. Children from poor households were most affected by the crisis. Lead is a dangerous neurotoxin. Elevated lead levels are linked to slowed physical development; low IQ; problems with cognition, attention, and memory; and learning disabilities.

In Flint approximately 150 local nurses and nursing students answered the call, organizing and arranging educational seminars, as well as setting up lead testing clinics to determine who had been affected by the water contamination. A nursing student involved in the effort told CBS Detroit that this situation has illustrated that "the need for health care, the need for nursing, goes way outside the hospital walls." See Figure 3.5[37] for an image of the water crisis in Flint, Michigan.

Reflective Questions

- What factors led to the children from poor households being so adversely harmed by this crisis?

- What are ways that you as a future nurse can make a difference for vulnerable or marginalized people?

Providing culturally responsive care is a key strategy for reducing health disparities.[38] While there are multiple determinants contributing to a person’s health, nurses play an important role in reducing health disparities by providing a culturally sensitive environment, performing a cultural assessment, and providing culturally responsive care. These interventions will be further discussed in the following sections. On the other hand, a lack of culturally responsive care potentially contributes to miscommunication between the patient and the nurse. The patient may experience distress or loss of trust in the nurse or the health care system as a whole and may not adhere to prescribed treatments. Nurses are uniquely positioned to directly impact patient outcomes as we become more aware of unacceptable health disparities and work together to overcome them.[39]