Scope of Practice

1.3 Health Care Settings & Team

Health Care Settings

There are several levels of health care including primary, secondary, and tertiary care. Each of these levels focuses on different aspects of health care and is typically provided in different settings.

Primary Care

Primary care promotes wellness and prevents disease. This care includes health promotion, education, protection (such as immunizations), early disease screening, and environmental considerations. Settings providing this type of health care include physician offices, public health clinics, school nursing, and community health nursing.

Secondary care

Secondary care occurs when a person has contracted an illness or injury and requires medical care. Secondary care is often referred to as acute care. Secondary care can range from uncomplicated care to repair a small laceration or treat a strep throat infection to more complicated emergent care such as treating a head injury sustained in an automobile accident. Whatever the problem, the patient needs medical and nursing attention to return to a state of health and wellness. Secondary care is provided in settings such as physician offices, clinics, urgent care facilities, or hospitals. Specialized units include areas such as burn care, neurosurgery, cardiac surgery, and transplant services.

Tertiary Care

Tertiary care addresses the long-term effects from chronic illnesses or conditions with the purpose to restore a patient’s maximum physical and mental function. The goal of tertiary care is to achieve the highest level of functioning possible while managing the chronic illness. For example, a patient who falls and fractures their hip will need secondary care to set the broken bones, but may need tertiary care to regain their strength and ability to walk even after the bones have healed. Patients with incurable diseases, such as dementia, may need specialized tertiary care to provide support they need for daily functioning. Tertiary care settings include rehabilitation units, assisted living facilities, adult day care, skilled nursing units, home care, and hospice centers.

Health Care Team

No matter the setting, quality health care requires a team of health care professionals collaboratively working together to deliver holistic, individualized care. Nursing students must be aware of the roles and contributions of various health care team members. The health care team consists of health care providers, nurses (licensed practical nurses, registered nurses, and advanced registered nurses), unlicensed assistive personnel, and a variety of interprofessional team members.

Health Care Providers

The Wisconsin Nurse Practice Act defines a provider as, “A physician, podiatrist, dentist, optometrist, or advanced practice nurse.”[1] Providers are responsible for ordering diagnostic tests such as blood work and X-rays, diagnosing a patient’s medical condition, developing a medical treatment plan, and prescribing medications. In a hospital setting, the medical treatment plan developed by a provider is communicated in the “History and Physical” component of the patient’s medical record with associated prescriptions (otherwise known as “orders”). Prescriptions or “orders” include diagnostic and laboratory tests, medications, and general parameters regarding the care that each patient is to receive. Nurses should respectfully clarify prescriptions they have questions or concerns about to ensure safe patient care. Providers typically visit hospitalized patients daily in what is referred to as “rounds.” It is helpful for nurses and nursing students to attend provider rounds for their assigned patients to be aware of and provide input regarding the current medical treatment plan, seek clarification, or ask questions. This helps to ensure that the provider, nurse, and patient have a clear understanding of the goals of care and minimize the need for follow-up phone calls.

Nurses

There are three levels of nurses as defined by each state’s Nurse Practice Act: Licensed Practical Nurse/Vocational Nurse (LPN/LVN), Registered Nurse (RN), and Advanced Practice Nurse (APRN).

Licensed Practical/Vocational Nurses

The NCSBN defines a licensed practical nurse (LPN) as, “An individual who has completed a state-approved practical or vocational nursing program, passed the NCLEX-PN examination, and is licensed by a state board of nursing to provide patient care.”[2] In some states, the term licensed vocational nurse (LVN) is used. LPN/LVNs typically work under the supervision of a registered nurse, advanced practice registered nurse, or physician.[3] LPNs provide “basic nursing care” and work with stable and/or chronically ill populations. Basic nursing care is defined by the Wisconsin Nurse Practice Act as “care that can be performed following a defined nursing procedure with minimal modification in which the responses of the patient to the nursing care are predictable.”[4] LPN/LVNs typically collect patient assessment information, administer medications, and perform nursing procedures according to their scope of practice in that state. The Open RN Nursing Skills textbook discusses the skills and procedures that LPNs frequently perform in Wisconsin. See the following box for additional details about the scope of practice of the Licensed Practical Nurse in Wisconsin.

Scope of Practice for Licensed Practical Nurses in Wisconsin

The Wisconsin Nurse Practice Act defines the scope of practice for Licensed Practical Nurses as the following: “In the performance of acts in basic patient situations, the LPN shall, under the general supervision of an RN or the direction of a provider:

(a) Accept only patient care assignments which the LPN is competent to perform.

(b) Provide basic nursing care.

(c) Record nursing care given and report to the appropriate person changes in the condition of a patient.

(d) Consult with a provider in cases where an LPN knows or should know a delegated act may harm a patient.

(e) Perform the following other acts when applicable:

- Assist with the collection of data.

- Assist with the development and revision of a nursing care plan.

- Reinforce the teaching provided by an RN provider and provide basic health care instruction.

- Participate with other health team members in meeting basic patient needs.”[5]

Registered Nurses

The NCSBN defines a Registered Nurse as “An individual who has graduated from a state-approved school of nursing, passed the NCLEX-RN examination and is licensed by a state board of nursing to provide patient care.”[6] Registered Nurses (RNs) use the nursing process as a critical thinking model as they make decisions and use clinical judgment regarding patient care. The nursing process is discussed in more detail in the “Nursing Process” chapter of this book. RNs may be delegated tasks from providers or may delegate tasks to LPNs and UAPs with supervision. See the following box for additional details about the scope of practice for Registered Nurses in the state of Wisconsin.

Scope of Practice for Registered Nurses in Wisconsin

(1) GENERAL NURSING PROCEDURES. An RN shall utilize the nursing process in the execution of general nursing procedures in the maintenance of health, prevention of illness or care of the ill. The nursing process consists of the steps of assessment, planning, intervention, and evaluation. This standard is met through performance of each of the following steps of the nursing process:

(a) Assessment. Assessment is the systematic and continual collection and analysis of data about the health status of a patient culminating in the formulation of a nursing diagnosis.

(b) Planning. Planning is developing a nursing plan of care for a patient, which includes goals and priorities derived from the nursing diagnosis.

(c) Intervention. Intervention is the nursing action to implement the plan of care by directly administering care or by directing and supervising nursing acts delegated to LPNs or less skilled assistants.

(d) Evaluation. Evaluation is the determination of a patient’s progress or lack of progress toward goal achievement, which may lead to modification of the nursing diagnosis.

(2) PERFORMANCE OF DELEGATED ACTS. In the performance of delegated acts, an RN shall do all of the following:

(a) Accept only those delegated acts for which there are protocols or written or verbal orders.

(b) Accept only those delegated acts for which the RN is competent to perform based on his or her nursing education, training or experience.

(c) Consult with a provider in cases where the RN knows or should know a delegated act may harm a patient.

(d) Perform delegated acts under the general supervision or direction of provider.

(3) SUPERVISION AND DIRECTION OF DELEGATED ACTS. In the supervision and direction of delegated acts, an RN shall do all of the following:

(a) Delegate tasks commensurate with educational preparation and demonstrated abilities of the person supervised.

(b) Provide direction and assistance to those supervised.

(c) Observe and monitor the activities of those supervised.

(d) Evaluate the effectiveness of acts performed under supervision.[7]

Advanced Practice Nurses

Advanced Practice Nurses (APRN) are defined by the NCSBN as an RN who has a graduate degree and advanced knowledge. There are four categories of Advanced Practice Nurses: certified nurse-midwife (CNM), clinical nurse specialist (CNS), certified nurse practitioner (CNP), and certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA). APRNs can diagnose illnesses and prescribe treatments and medications. Additional information about advanced nursing degrees and roles is provided in the box below.

Advanced Practice Nursing Roles[8]

Nurse Practitioners: Nurse practitioners (NPs) work in a variety of settings and complete physical examinations, diagnose and treat common acute illness and manage chronic illness, order laboratory and diagnostic tests, prescribe medications and other therapies, provide health teaching and supportive counseling with an emphasis on prevention of illness and health maintenance, and refer patients to other health professionals and specialists as needed. In many states, NPs can function independently and manage their own clinics, whereas in other states physician supervision is required. NP certifications include, but are not limited to, Family Practice, Adult-Gerontology Primary Care and Acute Care, and Psychiatric/Mental Health.

To read more about NP certification, visit Nursing World’s Our Certifications web page.

Clinical Nurse Specialists: Clinical Nurse Specialists (CNS) practice in a variety of health care environments and participate in mentoring other nurses, case management, research, designing and conducting quality improvement programs, and serving as educators and consultants. Specialty areas include, but are not limited to, Adult/Gerontology, Pediatrics, and Neonatal.

To read more about CNS certification, visit NACNS’s What is a CNS? web page.

Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists: Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists (CRNAs) administer anesthesia and related care before, during, and after surgical, therapeutic, diagnostic, and obstetrical procedures, as well as provide airway management during medical emergencies. CRNAs deliver more than 65 percent of all anesthetics to patients in the United States. Practice settings include operating rooms, dental offices, and outpatient surgical centers.

To read more about CRNA certification, visit NBCRNA’s website.

Certified Nurse Midwives: Certified Nurse Midwives provide gynecological exams, family planning advice, prenatal care, management of low-risk labor and delivery, and neonatal care. Practice settings include hospitals, birthing centers, community clinics, and patient homes.

To read more about CNM certification, visit AMCB Midwife’s website.

Unlicensed Assistive Personnel

Unlicensed Assistive Personnel (UAP) are defined by the NCSBN as, “Any unlicensed person, regardless of title, who performs tasks delegated by a nurse. This includes certified nursing aides/assistants (CNAs), patient care assistants (PCAs), patient care technicians (PCTs), state tested nursing assistants (STNAs), nursing assistants-registered (NA/Rs), or certified medication aides/assistants (MA-Cs). Certification of UAPs varies between jurisdictions.”[9]

CNAs, PCAs, and PCTs in Wisconsin generally work in hospitals and long-term care facilities and assist patients with daily tasks such as bathing, dressing, feeding, and toileting. They may also collect patient information such as vital signs, weight, and input/output as delegated by the nurse. The RN remains accountable that delegated tasks have been completed and documented by the UAP.

Interprofessional Team Members

Nurses, as the coordinator of a patient’s care, continuously review the plan of care to ensure all contributions of the multidisciplinary team are moving the patient toward expected outcomes and goals. The roles and contributions of interprofessional health care team members are further described in the following box.

Interprofessional Team Member Roles[10]

Dieticians: Dieticians assess, plan, implement, and evaluate interventions including those relating to dietary needs of those patients who need regular or therapeutic diets. They also provide dietary education and work with other members of the health care team when a client has dietary needs secondary to physical disorders such as dysphagia.

Occupational Therapists (OT): Occupational therapists assess, plan, implement, and evaluate interventions, including those that facilitate the patient’s ability to achieve their highest possible level of independence in their activities of daily living such as bathing, grooming, eating, and dressing. They also provide patients adaptive devices such as long shoe horns so the patient can put their shoes on, sock pulls so they can independently pull on socks, adaptive silverware to facilitate independent eating, grabbers so the patient can pick items up from the floor, and special devices to manipulate buttoning so the person can dress and button their clothing independently. Occupational therapists also assess the home for safety and the need for assistive devices when the patient is discharged home. They may recommend modifications to the home environment such as ramps, grab rails, and handrails to ensure safety and independence. Like physical therapists, occupational therapists practice in all health care environments including the home, hospital, and rehabilitation centers.

Pharmacists: Pharmacists ensure the safe prescribing and dispensing of medication and are a vital resource for nurses with questions or concerns about medications they are administering to patients. Pharmacists ensure that patients not only get the correct medication and dosing, but also have the guidance they need to use the medication safely and effectively.

Physical Therapists (PT): Physical therapists are licensed health care professionals who assess, plan, implement, and evaluate interventions including those related to the patient’s functional abilities in terms of their strength, mobility, balance, gait, coordination, and joint range of motion. They supervise prescribed exercise activities according to a patient’s condition and also provide and teach patients how to use assistive aids like walkers and canes and exercise regimens. Physical therapists practice in all health care environments including the home, hospital, and rehabilitation centers.

Podiatrists: Podiatrists provide care and services to patients who have foot problems. They often work with diabetic patients to clip toenails and provide foot care to prevent complications.

Prosthetists: Prosthetists design, fit, and supply the patient with an artificial body part such as a leg or arm prosthesis. They adjust prosthesis to ensure proper fit, patient comfort, and functioning.

Psychologists and Psychiatrists: Psychologists and psychiatrists provide mental health and psychiatric services to patients with mental health disorders and provide psychological support to family members and significant others as indicated.

Respiratory Therapists: Respiratory therapists treat respiratory-related conditions in patients. Their specialized respiratory care includes managing oxygen therapy; drawing arterial blood gases; managing patients on specialized oxygenation devices such as mechanical ventilators, CPAP, and Bi-PAP machines; administering respiratory medications like inhalers and nebulizers; intubating patients; assisting with bronchoscopy and other respiratory-related diagnostic tests; performing pulmonary hygiene measures like chest physiotherapy; and serving an integral role during cardiac and respiratory arrests.

Social Workers: Social workers counsel patients and provide psychological support, help set up community resources according to patients’ financial needs, and serve as part of the team that ensures continuity of care after the person is discharged.

Speech Therapists: Speech therapists assess, diagnose, and treat communication and swallowing disorders. For example, speech therapists help patients with a disorder called expressive aphasia. They also assist patients with using word boards and other electronic devices to facilitate communication. They assess patients with swallowing disorders called dysphagia and treat them in collaboration with other members of the health care team including nurses, dieticians, and health care providers.

Ancillary Department Members: Nurses also work with ancillary departments such as laboratory and radiology departments. Clinical laboratory departments provide a wide range of laboratory procedures that aid health care providers to diagnose, treat, and manage patients. These laboratories are staffed by medical technologists who test biological specimens collected from patients. Examples of laboratory tests performed include blood tests, blood banking, cultures, urine tests, and histopathology (changes in tissues caused by disease).[11]Radiology departments use imaging to assist providers in diagnosing and treating diseases seen within the body. They perform diagnostic tests such as X-rays, CTs, MRIs, nuclear medicine, PET scans, and ultrasound scans.

Chain of Command

Nurses rarely make patient decisions in isolation, but instead consult with other nurses and interprofessional team members. Concerns and questions about patient care are typically communicated according to that agency’s chain of command. In the military, chain of command refers to a hierarchy of reporting relationships – from the bottom to the top of an organization – regarding who must answer to whom. The chain of command not only establishes accountability, but also lays out lines of authority and decision-making power. The chain of command also applies to health care. For example, a registered nurse in a hospital may consult a “charge nurse,” who may consult the “nurse supervisor,” who may consult the “director of nursing,” who may consult the “vice president of nursing.” In a long-term care facility, a licensed practical/vocational nurse typically consults the registered nurse/charge nurse, who may consult with the director of nursing. Nursing students should always consult with their nursing instructor regarding questions or concerns about patient care before “going up the chain of command.”

Nurse Specialties

Registered nurses can obtain several types of certifications as a nurse specialist. Certification is the formal recognition of specialized knowledge, skills, and experience demonstrated by the achievement of standards identified by a nursing specialty. See the following box for descriptions of common nurse specialties.

Common Nurse Specialties

Critical Care Nurses provide care to patients with serious, complex, and acute illnesses or injuries that require very close monitoring and extensive medication protocols and therapies. Critical care nurses most often work in intensive care units of hospitals.

Public Health Nurses work to promote and protect the health of populations based on knowledge from nursing, social, and public health sciences. Public Health Nurses most often work in municipal and state health departments.

Home Health/Hospice Nurses provide a variety of nursing services for chronically ill patients and their caregivers in the home, including end-of-life care.

Occupational/Employee Health Nurses provide health screening, wellness programs and other health teaching, minor treatments, and disease/medication management services to people in the workplace. The focus is on promotion and restoration of health, prevention of illness and injury, and protection from work-related and environmental hazards.

Oncology Nurses care for patients with various types of cancer, administering chemotherapy and providing follow-up care, teaching, and monitoring. Oncology nurses work in hospitals, outpatient clinics, and patients’ homes.

Perioperative/Operating Room Nurses provide preoperative and postoperative care to patients undergoing anesthesia or assist with surgical procedures by selecting and handling instruments, controlling bleeding, and suturing incisions. These nurses work in hospitals and outpatient surgical centers.

Rehabilitation Nurses care for patients with temporary and permanent disabilities within inpatient and outpatient settings such as clinics and home health care.

Psychiatric/Mental Health Nurses specialize in mental and behavioral health problems and provide nursing care to individuals with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric nurses work in hospitals, outpatient clinics, and private offices.

School Nurses provide health assessment, intervention, and follow-up to maintain school compliance with health care policies and ensure the health and safety of staff and students. They administer medications and refer students for additional services when hearing, vision, and other issues become inhibitors to successful learning.

Other common specialty areas include a life span approach across health care settings and include maternal-child, neonatal, pediatric, and gerontological nursing.[12]

Now that we have discussed various settings where nurses work and various nursing roles, let’s review levels of nursing education and the national licensure exam (NCLEX).

- Wisconsin Administrative Code. (2018). Chapter N 6 standards of practice for registered nurses and licensed practical nurses. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/code/admin_code/n/6.pdf ↵

- NCSBN. https://www.ncsbn.org/ ↵

- NCSBN. https://www.ncsbn.org/index.htm ↵

- Wisconsin Administrative Code. (2018). Chapter N 6 standards of practice for registered nurses and licensed practical nurses. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/code/admin_code/n/6.pdf ↵

- Wisconsin Administrative Code. (2018). Chapter N 6 standards of practice for registered nurses and licensed practical nurses. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/code/admin_code/n/6.pdf ↵

- NCSBN. https://www.ncsbn.org/index.htm ↵

- Wisconsin Administrative Code. (2018). Chapter N 6 standards of practice for registered nurses and licensed practical nurses. https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/code/admin_code/n/6.pdf ↵

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Initiative on the Future of Nursing at the Institute of Medicine. (2011). The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. National Academies Press. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/12956/the-future-of-nursing-leading-change-advancing-health ↵

- NCSBN. https://www.ncsbn.org/index.htm ↵

- Burke, A. (2020, January 15). Collaboration with interdisciplinary team: NCLEX-RN. RegisteredNursing.org. https://www.registerednursing.org/nclex/collaboration-interdisciplinary-team/#collaborating-healthcare-members-disciplines-providing-client-care ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Bayot and Naidoo and licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Initiative on the Future of Nursing at the Institute of Medicine. (2011). The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. National Academies Press. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/12956/the-future-of-nursing-leading-change-advancing-health ↵

Let’s begin the journey of developing cultural competency by exploring basic concepts related to culture.

Culture and Subculture

Culture is a set of beliefs, attitudes, and practices shared by a group of people or community that is accepted, followed, and passed down to other members of the group. The word “culture” may at times be interchanged with terms such as ethnicity, nationality, or race. See Figure 3.1[1] for an illustration depicting culture by various nationalities. Cultural beliefs and practices bind group or community members together and help form a cohesive identity.[2],[3] Culture has an enduring influence on a person’s view of the world, expressed through language and communication patterns, family connections and kinship, religion, cuisine, dress, and other customs and rituals.[4] Culture is not static but is dynamic and ever-changing; it changes as members come into contact with beliefs from other cultures. For example, sushi is a traditional Asian dish that has become popular in America in recent years.

Nurses and other health care team members are impacted by their own personal cultural beliefs. For example, a commonly held belief in American health care is the importance of timeliness; medications are administered at specifically scheduled times, and appearing for appointments on time is considered crucial.

Most cultural beliefs are a combination of beliefs, values, and habits that have been passed down through family members and authority figures. The first step in developing cultural competence is to become aware of your own cultural beliefs, attitudes, and practices.

Nurses should also be aware of subcultures. A subculture is a smaller group of people within a culture, often based on a person’s occupation, hobbies, interests, or place of origin. People belonging to a subculture may identify with some, but not all, aspects of their larger “parent” culture. Members of the subculture share beliefs and commonalities that set them apart and do not always conform with those of the larger culture. See Table 3.2a for examples of subcultures.

Table 3.2a Examples of Subcultures

| Age/Generation | Baby Boomers, Millennials, Gen Z |

|---|---|

| Occupation | Truck Driver, Computer Scientist, Nurse |

| Hobbies/Interests | Birdwatchers, Gamers, Foodies, Skateboarders |

| Religion | Hinduism, Baptist, Islam |

| Gender | Male, Female, Nonbinary, Two-Spirit |

| Geography | Rural, Urban, Southern, Midwestern |

Culture is much more than a person’s nationality or ethnicity. Culture can be expressed in a multitude of ways, including the following:

- Language(s) spoken

- Religion and spiritual beliefs

- Gender identity

- Socioeconomic status

- Age

- Sexual orientation

- Geography

- Educational background

- Life experiences

- Living situation

- Employment status

- Immigration status

- Ability/Disability

People typically belong to more than one culture simultaneously. These cultures overlap, intersect, and are woven together to create a person’s cultural identity. In other words, the many ways in which a person expresses their cultural identity are not separated, but are closely intertwined, referred to as intersectionality.

Assimilation

Assimilation is the process of adopting or conforming to the practices, habits, and norms of a cultural group. As a result, the person gradually takes on a new cultural identity and may lose their original identity in the process.[5] An example of assimilation is a newly graduated nurse, who after several months of orientation on the hospital unit, offers assistance to a colleague who is busy. The new nurse has developed self-confidence in the role and has developed an understanding that helping others is a norm for the nurses on that unit.

Assimilation is not always voluntary, however, and may become a source of distress. There are historic examples of involuntary assimilation in many countries. For example, in the past, authorities in the United States and Canadian governments required indigenous children to attend boarding schools, separated them from their families, and punished them for speaking their native language.[6],[7]

Cultural Values and Beliefs

Culture provides an important source of values and comfort for patients, families, and communities. Think of culture as a thread that is woven through a person’s world and impacts one’s choices, perspectives, and way of life. It plays a role in all of a person’s life events and threads its way through the development of one’s self-concept, sexuality, and spirituality. It affects lifelong nutritional habits, as well as coping strategies with death and dying.

Culture influences how a patient interprets “good” health, as well as their perspectives on illness and the causes of illness. The manner in which pain is expressed is also shaped by a person’s culture. See Table 3.2b for additional examples of how a person’s culture impacts common values and beliefs regarding family patterns, communication patterns, space orientation, time orientation, and nutritional patterns. As you read Table 3.2b, take a moment to reflect on your own cultural background and your personally held beliefs for each of these concepts.

Table 3.2b Cultural Concepts

| Cultural Concepts | Examples of Culturally Influenced Values and Beliefs |

|---|---|

| Family Patterns | Family size

Views on contraception Roles of family members Naming customs Value placed on elders and children Discipline/upbringing of children Rites of passage End-of-life care |

| Communication Patterns | Eye contact

Touch Use of silence or humor Intonation, vocabulary, grammatical structure Topics considered personal (i.e., difficult to discuss) Greeting customs (handshakes, hugs) |

| Space Orientation | Personal distance and intimate space |

| Time Orientation | Focus on the past, present, or future

Importance of following a routine or schedule Arrival on time for appointments |

| Nutritional Patterns | Common meal choices

Foods to avoid Foods to heal or treat disease Religious practices (e.g., fasting, dietary restrictions) Foods to celebrate life events and holidays |

A person’s culture can also affect encounters with health care providers in other ways, such as the following:

- Level of family involvement in care

- Timing for seeking care

- Acceptance of treatment (as preventative measure or for an actual health problem)

- The accepted decision-maker (i.e., the patient or other family members)

- Use of home or folk remedies

- Seeking advice or treatment from nontraditional providers

- Acceptance of a caregiver of the opposite gender

Cultural Diversity and Cultural Humility

Cultural diversity is a term used to describe cultural differences among people. See Figure 3.2[8] for artwork depicting diversity. While it is useful to be aware of specific traits of a culture or subculture, it is just as important to understand that each individual is unique and there are always variations in beliefs among individuals within a culture. Nurses should, therefore, refrain from making assumptions about the values and beliefs of members of specific cultural groups.[9] Instead, a better approach is recognizing that culture is not a static, uniform characteristic but instead realizing there is diversity within every culture and in every person. The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines cultural humility as, "A humble and respectful attitude toward individuals of other cultures that pushes one to challenge their own cultural biases, realize they cannot possibly know everything about other cultures, and approach learning about other cultures as a lifelong goal and process."[10]

Current demographics in the United States reveal that the population is predominantly white. People who were born in another country, but now live in the United States, comprise approximately 14% of the nation’s total population. However, these demographics are rapidly changing. The United States Census Bureau projects that more than 50 percent of Americans will belong to a minority group by 2060. With an increasingly diverse population to care for, it is imperative for nurses to integrate culturally responsive care into their nursing practice.[11],[12] Creative a culturally responsive environment is discussed in a later subsection of this chapter.

Concepts Related to Culture

There are additional concepts related to culture that can impact a nurse’s ability to provide culturally responsive care, including stereotyping, ethnocentrism, discrimination, prejudice, and bias. See Table 3.2c for definitions and examples of these concepts.

Table 3.2c Concepts Related to Culture

| Concepts | Definitions | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Stereotyping | The assumption that a person has the attributes, traits, beliefs, and values of a cultural group because they are a member of that group. | The nurse teaches the daughter of an older patient how to make online doctor appointments, assuming that the older patient does not understand how to use a computer. |

| Ethnocentrism | The belief that one’s culture (or race, ethnicity, or country) is better and preferable than another’s. | The nurse disparages the patient’s use of nontraditional medicine and tells the patient that traditional treatments are superior. |

| Discrimination | The unfair and different treatment of another person or group, denying them opportunities and rights to participate fully in society. | A nurse manager refuses to hire a candidate for a nursing position because she is pregnant. |

| Prejudice | A prejudgment or preconceived idea, often unfavorable, about a person or group of people. | The nurse withholds pain medication from a patient with a history of opioid addiction. |

| Bias | An attitude, opinion, or inclination (positive or negative) towards a group or members of a group. Bias can be a conscious attitude (explicit) or an unconscious attitude where the person is not aware of their bias (implicit). | A patient does not want the nurse to care for them because the nurse has a tattoo. |

Race is a socially constructed idea because there are no true genetically- or biologically-distinct races. Humans are not biologically different from each other. Racism presumes that races are distinct from one another, and there is a hierarchy to race, implying that races are unequal. Ernest Grant, president of the American Nurses Association (ANA), recently declared that nurses are obligated “to speak up against racism, discrimination, and injustice. This is non-negotiable.”[13] As frontline health care providers, nurses have an obligation to recognize the impact of racism on their patients and the communities they serve.[14]

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Culture can exert a powerful influence on a person’s sexual orientation and gender expression. Sexual orientation refers to a person’s physical and emotional interest or desire for others. Sexual orientation is on a continuum and is manifested in one’s self-identity and behaviors.[15] The acronym LGBTQ stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or questioning in reference to sexual orientation. (A “+” is sometimes added after LGBTQ to capture additional orientations). See Figure 3.3[16] for an image of participants in a LGBTQ rally in Dublin. Historically, individuals within the LGBTQ community have experienced discrimination and prejudice from health care providers and avoided or delayed health care due to these negative experiences. Despite increased recognition of this group of people in recent years, members of the LGBTQ community continue to experience significant health disparities. Persistent cultural bias and stigmatization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBTQ) people have also been shown to contribute to higher rates of substance abuse and suicide rates in this population.[17],[18],[19]

Gender identity refers to a person’s inner sensibility that they are a man, a woman, or perhaps neither. Cisgender is the term used to describe a person whose identity matches their sex assigned at birth.[20] To the extent that a person’s gender identity does not conform with the sex assigned to them at birth, they may identify as transgender or as gender nonbinary. Transgender people, like cisgender people, “may be sexually oriented toward men, women, both sexes, or neither sex.”[21] Gender expression refers to a person’s outward demonstration of gender in relation to societal norms, such as in style of dress, hairstyle, or other mannerisms.[22]Sharing pronouns as part of a basic introduction to a patient can assist a transgender patient to feel secure sharing their pronouns in a health care setting. Asking a patient for their pronoun (he, she, they, ze, etc.) is considered part of a nursing assessment.

Related Ethical Considerations

Justice, a principle and moral obligation to act on the basis of equality and equity, is a standard linked to fairness for all in society.[23] The ANA states this obligation guarantees not only basic rights (respect, human dignity, autonomy, security, and safety) but also fairness in all operations of societal structures. This includes care being delivered with fairness, rightness, correctness, unbiasedness, and inclusiveness while being based on well-founded reason and evidence.[24]

Social justice is related to respect, equity, and inclusion. The ANA defines social justice as equal rights, equal treatment, and equitable opportunities for all.[25] The ANA further states, "Nurses need to model the profession's commitment to social justice and health through actions and advocacy to address the social determinants of health and promote well-being in all settings within society."[26] Social determinants of health are nonmedical factors that influence health outcomes, including conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider sets of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.[27] Health outcomes impacted by social determinants of health are referred to as health disparities. Health disparities are further discussed in a subsection later in this chapter.

Let’s begin the journey of developing cultural competency by exploring basic concepts related to culture.

Culture and Subculture

Culture is a set of beliefs, attitudes, and practices shared by a group of people or community that is accepted, followed, and passed down to other members of the group. The word “culture” may at times be interchanged with terms such as ethnicity, nationality, or race. See Figure 3.1[28] for an illustration depicting culture by various nationalities. Cultural beliefs and practices bind group or community members together and help form a cohesive identity.[29],[30] Culture has an enduring influence on a person’s view of the world, expressed through language and communication patterns, family connections and kinship, religion, cuisine, dress, and other customs and rituals.[31] Culture is not static but is dynamic and ever-changing; it changes as members come into contact with beliefs from other cultures. For example, sushi is a traditional Asian dish that has become popular in America in recent years.

Nurses and other health care team members are impacted by their own personal cultural beliefs. For example, a commonly held belief in American health care is the importance of timeliness; medications are administered at specifically scheduled times, and appearing for appointments on time is considered crucial.

Most cultural beliefs are a combination of beliefs, values, and habits that have been passed down through family members and authority figures. The first step in developing cultural competence is to become aware of your own cultural beliefs, attitudes, and practices.

Nurses should also be aware of subcultures. A subculture is a smaller group of people within a culture, often based on a person’s occupation, hobbies, interests, or place of origin. People belonging to a subculture may identify with some, but not all, aspects of their larger “parent” culture. Members of the subculture share beliefs and commonalities that set them apart and do not always conform with those of the larger culture. See Table 3.2a for examples of subcultures.

Table 3.2a Examples of Subcultures

| Age/Generation | Baby Boomers, Millennials, Gen Z |

|---|---|

| Occupation | Truck Driver, Computer Scientist, Nurse |

| Hobbies/Interests | Birdwatchers, Gamers, Foodies, Skateboarders |

| Religion | Hinduism, Baptist, Islam |

| Gender | Male, Female, Nonbinary, Two-Spirit |

| Geography | Rural, Urban, Southern, Midwestern |

Culture is much more than a person’s nationality or ethnicity. Culture can be expressed in a multitude of ways, including the following:

- Language(s) spoken

- Religion and spiritual beliefs

- Gender identity

- Socioeconomic status

- Age

- Sexual orientation

- Geography

- Educational background

- Life experiences

- Living situation

- Employment status

- Immigration status

- Ability/Disability

People typically belong to more than one culture simultaneously. These cultures overlap, intersect, and are woven together to create a person’s cultural identity. In other words, the many ways in which a person expresses their cultural identity are not separated, but are closely intertwined, referred to as intersectionality.

Assimilation

Assimilation is the process of adopting or conforming to the practices, habits, and norms of a cultural group. As a result, the person gradually takes on a new cultural identity and may lose their original identity in the process.[32] An example of assimilation is a newly graduated nurse, who after several months of orientation on the hospital unit, offers assistance to a colleague who is busy. The new nurse has developed self-confidence in the role and has developed an understanding that helping others is a norm for the nurses on that unit.

Assimilation is not always voluntary, however, and may become a source of distress. There are historic examples of involuntary assimilation in many countries. For example, in the past, authorities in the United States and Canadian governments required indigenous children to attend boarding schools, separated them from their families, and punished them for speaking their native language.[33],[34]

Cultural Values and Beliefs

Culture provides an important source of values and comfort for patients, families, and communities. Think of culture as a thread that is woven through a person’s world and impacts one’s choices, perspectives, and way of life. It plays a role in all of a person’s life events and threads its way through the development of one’s self-concept, sexuality, and spirituality. It affects lifelong nutritional habits, as well as coping strategies with death and dying.

Culture influences how a patient interprets “good” health, as well as their perspectives on illness and the causes of illness. The manner in which pain is expressed is also shaped by a person’s culture. See Table 3.2b for additional examples of how a person’s culture impacts common values and beliefs regarding family patterns, communication patterns, space orientation, time orientation, and nutritional patterns. As you read Table 3.2b, take a moment to reflect on your own cultural background and your personally held beliefs for each of these concepts.

Table 3.2b Cultural Concepts

| Cultural Concepts | Examples of Culturally Influenced Values and Beliefs |

|---|---|

| Family Patterns | Family size

Views on contraception Roles of family members Naming customs Value placed on elders and children Discipline/upbringing of children Rites of passage End-of-life care |

| Communication Patterns | Eye contact

Touch Use of silence or humor Intonation, vocabulary, grammatical structure Topics considered personal (i.e., difficult to discuss) Greeting customs (handshakes, hugs) |

| Space Orientation | Personal distance and intimate space |

| Time Orientation | Focus on the past, present, or future

Importance of following a routine or schedule Arrival on time for appointments |

| Nutritional Patterns | Common meal choices

Foods to avoid Foods to heal or treat disease Religious practices (e.g., fasting, dietary restrictions) Foods to celebrate life events and holidays |

A person’s culture can also affect encounters with health care providers in other ways, such as the following:

- Level of family involvement in care

- Timing for seeking care

- Acceptance of treatment (as preventative measure or for an actual health problem)

- The accepted decision-maker (i.e., the patient or other family members)

- Use of home or folk remedies

- Seeking advice or treatment from nontraditional providers

- Acceptance of a caregiver of the opposite gender

Cultural Diversity and Cultural Humility

Cultural diversity is a term used to describe cultural differences among people. See Figure 3.2[35] for artwork depicting diversity. While it is useful to be aware of specific traits of a culture or subculture, it is just as important to understand that each individual is unique and there are always variations in beliefs among individuals within a culture. Nurses should, therefore, refrain from making assumptions about the values and beliefs of members of specific cultural groups.[36] Instead, a better approach is recognizing that culture is not a static, uniform characteristic but instead realizing there is diversity within every culture and in every person. The American Nurses Association (ANA) defines cultural humility as, "A humble and respectful attitude toward individuals of other cultures that pushes one to challenge their own cultural biases, realize they cannot possibly know everything about other cultures, and approach learning about other cultures as a lifelong goal and process."[37]

Current demographics in the United States reveal that the population is predominantly white. People who were born in another country, but now live in the United States, comprise approximately 14% of the nation’s total population. However, these demographics are rapidly changing. The United States Census Bureau projects that more than 50 percent of Americans will belong to a minority group by 2060. With an increasingly diverse population to care for, it is imperative for nurses to integrate culturally responsive care into their nursing practice.[38],[39] Creative a culturally responsive environment is discussed in a later subsection of this chapter.

Concepts Related to Culture

There are additional concepts related to culture that can impact a nurse’s ability to provide culturally responsive care, including stereotyping, ethnocentrism, discrimination, prejudice, and bias. See Table 3.2c for definitions and examples of these concepts.

Table 3.2c Concepts Related to Culture

| Concepts | Definitions | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Stereotyping | The assumption that a person has the attributes, traits, beliefs, and values of a cultural group because they are a member of that group. | The nurse teaches the daughter of an older patient how to make online doctor appointments, assuming that the older patient does not understand how to use a computer. |

| Ethnocentrism | The belief that one’s culture (or race, ethnicity, or country) is better and preferable than another’s. | The nurse disparages the patient’s use of nontraditional medicine and tells the patient that traditional treatments are superior. |

| Discrimination | The unfair and different treatment of another person or group, denying them opportunities and rights to participate fully in society. | A nurse manager refuses to hire a candidate for a nursing position because she is pregnant. |

| Prejudice | A prejudgment or preconceived idea, often unfavorable, about a person or group of people. | The nurse withholds pain medication from a patient with a history of opioid addiction. |

| Bias | An attitude, opinion, or inclination (positive or negative) towards a group or members of a group. Bias can be a conscious attitude (explicit) or an unconscious attitude where the person is not aware of their bias (implicit). | A patient does not want the nurse to care for them because the nurse has a tattoo. |

Race is a socially constructed idea because there are no true genetically- or biologically-distinct races. Humans are not biologically different from each other. Racism presumes that races are distinct from one another, and there is a hierarchy to race, implying that races are unequal. Ernest Grant, president of the American Nurses Association (ANA), recently declared that nurses are obligated “to speak up against racism, discrimination, and injustice. This is non-negotiable.”[40] As frontline health care providers, nurses have an obligation to recognize the impact of racism on their patients and the communities they serve.[41]

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Culture can exert a powerful influence on a person’s sexual orientation and gender expression. Sexual orientation refers to a person’s physical and emotional interest or desire for others. Sexual orientation is on a continuum and is manifested in one’s self-identity and behaviors.[42] The acronym LGBTQ stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or questioning in reference to sexual orientation. (A “+” is sometimes added after LGBTQ to capture additional orientations). See Figure 3.3[43] for an image of participants in a LGBTQ rally in Dublin. Historically, individuals within the LGBTQ community have experienced discrimination and prejudice from health care providers and avoided or delayed health care due to these negative experiences. Despite increased recognition of this group of people in recent years, members of the LGBTQ community continue to experience significant health disparities. Persistent cultural bias and stigmatization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBTQ) people have also been shown to contribute to higher rates of substance abuse and suicide rates in this population.[44],[45],[46]

Gender identity refers to a person’s inner sensibility that they are a man, a woman, or perhaps neither. Cisgender is the term used to describe a person whose identity matches their sex assigned at birth.[47] To the extent that a person’s gender identity does not conform with the sex assigned to them at birth, they may identify as transgender or as gender nonbinary. Transgender people, like cisgender people, “may be sexually oriented toward men, women, both sexes, or neither sex.”[48] Gender expression refers to a person’s outward demonstration of gender in relation to societal norms, such as in style of dress, hairstyle, or other mannerisms.[49]Sharing pronouns as part of a basic introduction to a patient can assist a transgender patient to feel secure sharing their pronouns in a health care setting. Asking a patient for their pronoun (he, she, they, ze, etc.) is considered part of a nursing assessment.

Related Ethical Considerations

Justice, a principle and moral obligation to act on the basis of equality and equity, is a standard linked to fairness for all in society.[50] The ANA states this obligation guarantees not only basic rights (respect, human dignity, autonomy, security, and safety) but also fairness in all operations of societal structures. This includes care being delivered with fairness, rightness, correctness, unbiasedness, and inclusiveness while being based on well-founded reason and evidence.[51]

Social justice is related to respect, equity, and inclusion. The ANA defines social justice as equal rights, equal treatment, and equitable opportunities for all.[52] The ANA further states, "Nurses need to model the profession's commitment to social justice and health through actions and advocacy to address the social determinants of health and promote well-being in all settings within society."[53] Social determinants of health are nonmedical factors that influence health outcomes, including conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider sets of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.[54] Health outcomes impacted by social determinants of health are referred to as health disparities. Health disparities are further discussed in a subsection later in this chapter.

Th Patient's Bill of Rights is an evolving document related to providing culturally competent care. In 1973 the American Hospital Association (AHA) adopted the Patient’s Bill of Rights.[55] See the following box to review the original Patient’s Bill of Rights. The bill has since been updated, revised, and adapted for use throughout the world in all health care settings. There are different versions of the bill, but, in general, it safeguards a patient’s right to accurate and complete information, fair treatment, and self-determination when making health care decisions. Patients should expect to be treated with sensitivity and dignity and with respect for their cultural values. While the Patient’s Bill of Rights extends beyond the scope of cultural considerations, its basic principles underscore the importance of cultural competency when caring for people.

Patient’s Bill of Rights[56]

- The patient has the right to considerate and respectful care.

- The patient has the right to and is encouraged to obtain from physicians and other direct caregivers relevant, current, and understandable information concerning diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis.

- Except in emergencies when the patient lacks decision-making capacity and the need for treatment is urgent, the patient is entitled to the opportunity to discuss and request information related to the specific procedures and/or treatments, the risks involved, the possible length of recuperation, and the medically reasonable alternatives and their accompanying risks and benefits.

- Patients have the right to know the identity of physicians, nurses, and others involved in their care, as well as when those involved are students, residents, or other trainees.

- The patient has the right to know the immediate and long-term financial implications of treatment choices, insofar as they are known.

- The patient has the right to make decisions about the plan of care prior to and during the course of treatment and to refuse a recommended treatment or plan of care to the extent permitted by law and hospital policy and to be informed of the medical consequences of this action. In case of such refusal, the patient is entitled to other appropriate care and services that the hospital provides or transfer to another hospital. The hospital should notify patients of any policy that might affect patient choice within the institution.

- The patient has the right to have an advance directive (such as a living will, health care proxy, or durable power of attorney for health care) concerning treatment or designating a surrogate decision-maker with the expectation that the hospital will honor the intent of that directive to the extent permitted by law and hospital policy. Health care institutions must advise patients of their rights under state law and hospital policy to make informed medical choices, ask if the patient has an advance directive, and include that information in patient records. The patient has the right to timely information about hospital policy that may limit its ability to implement fully a legally valid advance directive.

- The patient has the right to every consideration of privacy. Case discussion, consultation, examination, and treatment should be conducted so as to protect each patient’s privacy.

- The patient has the right to expect that all communications and records pertaining to his/her care will be treated as confidential by the hospital, except in cases such as suspected abuse and public health hazards when reporting is permitted or required by law. The patient has the right to expect that the hospital will emphasize the confidentiality of this information when it releases it to any other parties entitled to review information in these records.

- The patient has the right to review the records pertaining to his/her medical care and to have the information explained or interpreted as necessary, except when restricted by law.

- The patient has the right to expect that, within its capacity and policies, a hospital will make a reasonable response to the request of a patient for appropriate and medically indicated care and services. The hospital must provide evaluation, service, and/or referral as indicated by the urgency of the case. When medically appropriate and legally permissible, or when a patient has so requested, a patient may be transferred to another facility. The institution to which the patient is to be transferred must first have accepted the patient for transfer. The patient must also have the benefit of complete information and explanation concerning the need for, risks, benefits, and alternatives to such a transfer.

- The patient has the right to ask and be informed of the existence of business relationships among the hospital, educational institutions, other health care providers, or payers that may influence the patient’s treatment and care.

- The patient has the right to consent to or decline to participate in proposed research studies or human experimentation affecting care and treatment or requiring direct patient involvement and to have those studies fully explained prior to consent. A patient who declines to participate in research or experimentation is entitled to the most effective care that the hospital can otherwise provide.

- The patient has the right to expect reasonable continuity of care when appropriate and to be informed by physicians and other caregivers of available and realistic patient care options when hospital care is no longer appropriate.

- The patient has the right to be informed of hospital policies and practices that relate to patient care, treatment, and responsibilities. The patient has the right to be informed of available resources for resolving disputes, grievances, and conflicts, such as ethics committees, patient representatives, or other mechanisms available in the institution. The patient has the right to be informed of the hospital’s charges for services and available payment methods.

Read a current version of the "Patient Care Partnership" brochure from the American Hospital Association that has replaced the Patient's Bill of Rights.

Despite decades of promoting cultural competent care and the Patient's Bill of Rights, disparities in health care continue. Vulnerable populations continue to experience increased prevalence and burden of diseases, as well as problems accessing quality health care. In 2003 the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, sharing evidence that “bias, prejudice, and stereotyping on the part of health care providers may contribute to differences in care.”[57] The health care system in the United States was shaped by the values and beliefs of mainstream white culture and originally designed to primarily serve English-speaking patients with financial resources.[58] In addition, most health care professionals in the United States are members of the white culture and medical treatments tend to arise from that perspective.[59],[60]

The term health disparities describes the differences in health outcomes that result from social determinants of health. Social determinants of health are conditions in the environment where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes. Resources that enhance quality of life can have a significant influence on population health outcomes. Examples of resources include safe and affordable housing, access to education, public safety, availability of healthy foods, local emergency/health services, and environments free of life-threatening toxins.[61]

Vulnerable populations experience increased prevalence and burden of diseases, as well as problems accessing quality health care because of social determinants of health. Health disparities negatively impact groups of people based on their ethnicity, gender, age, mental health, disability, sexual orientation, gender identity, socioeconomic status, geographic location, or other characteristics historically linked to discrimination or exclusion.[62] A related term is health care disparity that refers to differences in access to health care and insurance coverage. Health disparities and health care disparities can lead to decreased quality of life, increased personal costs, and lower life expectancy. More broadly, these disparities also translate to greater societal costs, such as the financial burden of uncontrolled chronic illnesses.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) releases an annual National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report that provides a comprehensive overview of the quality of health care received by the general U.S. population and disparities in care experienced by different racial and socioeconomic groups. Quality is described in terms of patient safety, person-centered care, care coordination, effective treatment, healthy living, and care affordability.[63] Although access to health care and quality have improved since 2000 in the wake of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the 2019 report shows continued disparities, especially for poor and uninsured populations:

- For about 40% of quality measures, Blacks, African Americans, and Alaska Natives received worse care than Whites. For more than one third of quality measures, Hispanics received worse care than Whites.

- For nearly a quarter of quality measures, residents of large metropolitan areas received worse care than residents of suburban areas. For one third of quality measures, residents of rural areas received worse care than residents of suburban areas.[64]

There are several initiatives and agencies designed to combat the problem of health disparities in the United States. See Table 3.5 for a list of hyperlinks to available resources to combat health disparities.

Table 3.5 Resources to Combat Health Disparities

| AHRQ publishes the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report, a report on measures related to access to care, affordable care, care coordination, effective treatment, healthy living, patient safety, and person-centered care. | |

| A new Healthy People initiative is launched every ten years. The initiative guides national health promotion and disease prevention efforts to improve the health of the nation. | |

| The mission of the Office of Minority Health is to improve the health of minority populations and to act as a resource for health care providers. The Office of Minority Health has published National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health and Health Care (CLAS). | |

|

Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health Across the United States (REACH-US) |

This initiative, overseen by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), seeks to remove barriers to health linked to race or ethnicity, education, income, location, or other social factors. |

|

National Partnership for Action to End Health Disparities (NPA) |

The mission of the NPA is to raise awareness and increase the effectiveness of programs targeting health disparities. |

| RWJF is a philanthropic organization with the goal of identifying the root causes of health disparities and removing barriers to improve health outcomes. | |

| The nonprofit Sullivan Alliance was formed to increase the numbers of ethnic and racial minorities within the health professions to raise awareness about health disparities and to develop partnerships between academia and the health professions. | |

|

Transcultural Nursing Society – Many Cultures One World (TCNS) |

The mission of TCNS is to improve the quality of culturally congruent and equitable care for people worldwide by ensuring cultural competence in nursing practice, scholarship, education, research, and administration. |

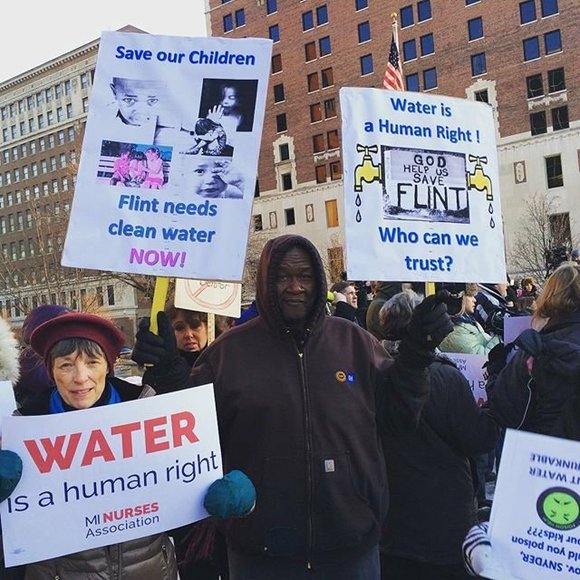

See the following box for an example of nurses addressing a community health care disparity during the water crisis in Flint, Michigan.

Nurses Addressing the Flint Michigan Water Crisis[65]

In 2014 the water system in Flint, Michigan, was discovered to be contaminated with lead. The city’s children were found to have perilously elevated lead levels. Children from poor households were most affected by the crisis. Lead is a dangerous neurotoxin. Elevated lead levels are linked to slowed physical development; low IQ; problems with cognition, attention, and memory; and learning disabilities.

In Flint approximately 150 local nurses and nursing students answered the call, organizing and arranging educational seminars, as well as setting up lead testing clinics to determine who had been affected by the water contamination. A nursing student involved in the effort told CBS Detroit that this situation has illustrated that "the need for health care, the need for nursing, goes way outside the hospital walls." See Figure 3.5[66] for an image of the water crisis in Flint, Michigan.

Reflective Questions

- What factors led to the children from poor households being so adversely harmed by this crisis?

- What are ways that you as a future nurse can make a difference for vulnerable or marginalized people?

Providing culturally responsive care is a key strategy for reducing health disparities.[67] While there are multiple determinants contributing to a person’s health, nurses play an important role in reducing health disparities by providing a culturally sensitive environment, performing a cultural assessment, and providing culturally responsive care. These interventions will be further discussed in the following sections. On the other hand, a lack of culturally responsive care potentially contributes to miscommunication between the patient and the nurse. The patient may experience distress or loss of trust in the nurse or the health care system as a whole and may not adhere to prescribed treatments. Nurses are uniquely positioned to directly impact patient outcomes as we become more aware of unacceptable health disparities and work together to overcome them.[68]

The freedom to express one’s cultural beliefs is a fundamental right of all people. Nurses realize that people speak, behave, and act in many different ways due to the influential role that culture plays in their lives and their view of the world. Cultural competence is a lifelong process of applying evidence-based nursing in agreement with the cultural values, beliefs, worldview, and practices of patients to produce improved patient outcomes.[69],[70],[71]

Culturally-competent care requires nurses to combine their knowledge and skills with awareness, curiosity, and sensitivity about their patients’ cultural beliefs. It takes motivation, time, and practice to develop cultural competence, and it will evolve throughout your nursing career. Culturally competent nurses have the power to improve the quality of care leading to better health outcomes for culturally diverse patients. Nurses who accept and uphold the cultural values and beliefs of their patients are more likely to develop supportive and trusting relationships with their patients. In turn, this opens the way for optimal disease and injury prevention and leads towards positive health outcomes for all patients .

The roots of providing culturally-competent care are based on the original transcultural nursing theory developed by Dr. Madeleine Leininger. Transcultural nursing incorporates cultural beliefs and practices of individuals to help them maintain and regain health or to face death in a meaningful way.[72] See Figure 3.4[73] for an image of Dr. Leininger. Read more about transcultural nursing theory in the following box.

Madeleine Leininger and the Transcultural Nursing Theory[74]

Dr. Madeleine Leininger (1925-2012) founded the transcultural nursing theory. She was the first professional nurse to obtain a PhD in anthropology. She combined the "culture" concept from anthropology with the "care" concept from nursing and reformulated these concepts into "culture care."

In the mid-1950s, no cultural knowledge base existed to guide nursing decisions or understand cultural behaviors as a way of providing therapeutic care. Leininger wrote the first books in the field and coined the term "culturally congruent care." She developed and taught the first transcultural nursing course in 1966, and master's and doctoral programs in transcultural nursing were launched shortly after. Dr. Leininger was honored as a Living Legend of the American Academy of Nursing in 1998.

Nurses have an ethical and moral obligation to provide culturally competent care to the patients they serve.[75] The "Respectful and Equitable Practice" Standard of Professional Performance set by the American Nurses Association (ANA) states that nurses must practice with cultural humility and inclusiveness. The ANA Code of Ethics also states that the nurse should collaborate with other health professionals, as well as the public, to protect human rights, fight discriminatory practices, and reduce disparities.[76] Additionally, the ANA Code of Ethics also states that nurses “are expected to be aware of their own cultural identifications in order to control their personal biases that may interfere with the therapeutic relationship. Self-awareness involves not only examining one’s culture but also examining perceptions and assumptions about the patient’s culture...nurses should possess knowledge and understanding how oppression, racism, discrimination, and stereotyping affect them personally and in their work."[77]

Developing cultural competence begins in nursing school.[78],[79] Culture is an integral part of life, but its impact is often implicit. It is easy to assume that others share the same cultural values that you do, but each individual has their own beliefs, values, and preferences. Begin the examination of your own cultural beliefs and feelings by answering the questions below.[80]

Reflect on the following questions carefully and contemplate your responses as you begin your journey of providing culturally responsive care as a nurse. (Questions are adapted from the Anti Defamation League's “Imagine a World Without Hate” Personal Self-Assessment Anti-Bias Behavior).[81]

- Who are you? With what cultural group or subgroups do you identify?

- When you meet someone from another culture/country/place, do you try to learn more about them?

- Do you notice instances of bias, prejudice, discrimination, and stereotyping against people of other groups or cultures in your environment (home, school, work, TV programs or movies, restaurants, places where you shop)?

- Have you reflected on your own upbringing and childhood to better understand your own implicit biases and the ways you have internalized messages you received?

- Do you ever consider your use of language to avoid terms or phrases that may be degrading or hurtful to other groups?

- When other people use biased language and behavior, do you feel comfortable speaking up and asking them to refrain?

- How ready are you to give equal attention, care, and support to people regardless of their culture, socioeconomic class, religion, gender expression, sexual orientation, or other “difference”?

The Process of Developing Cultural Competence

Dr. Josephine Campinha-Bacote is an influential nursing theorist and researcher who developed a model of cultural competence. The model asserts there are specific characteristics that a nurse becoming culturally competent possesses, including cultural awareness, cultural knowledge, cultural skill, and cultural encounters.[82]

Cultural awareness is a deliberate, cognitive process in which health care providers become appreciative and sensitive to the values, beliefs, attitudes, practices, and problem-solving strategies of a patient’s culture. To become culturally aware, the nurse must undergo reflective exploration of personal cultural values while also becoming conscious of the cultural practices of others. In addition to reflecting on one’s own cultural values, the culturally competent nurse seeks to reverse harmful prejudices, ethnocentric views, and attitudes they have. Cultural awareness goes beyond a simple awareness of the existence of other cultures and involves an interest, curiosity, and appreciation of other cultures. Although cultural diversity training is typically a requirement for health care professionals, cultural desire refers to the intrinsic motivation and commitment on the part of a nurse to develop cultural awareness and cultural competency.[83]

Acquiring cultural knowledge is another important step towards becoming a culturally competent nurse. Cultural knowledge refers to seeking information about cultural health beliefs and values to understand patients’ world views. To acquire cultural knowledge, the nurse actively seeks information about other cultures, including common practices, beliefs, values, and customs, particularly for those cultures that are prevalent within the communities they serve.[84] Cultural knowledge also includes understanding the historical backgrounds of culturally diverse groups in society, as well as physiological variations and the incidence of certain health conditions in culturally diverse groups. Cultural knowledge is best obtained through cultural encounters with patients from diverse backgrounds to learn about individual variations that occur within cultural groups and to prevent stereotyping.

While obtaining cultural knowledge, it is important to demonstrate cultural sensitivity. Cultural sensitivity means being tolerant and accepting of cultural practices and beliefs of people. Cultural sensitivity is demonstrated when the nurse conveys nonjudgmental interest and respect through words and action and an understanding that some health care treatments may conflict with a person’s cultural beliefs.[85] Cultural sensitivity also implies a consciousness of the damaging effects of stereotyping, prejudice, or biases on patients and their well-being. Nurses who fail to act with cultural sensitivity may be viewed as uncaring or inconsiderate, causing a breakdown in trust for the patient and their family members. When a patient experiences nursing care that contradicts with their cultural beliefs, they may experience moral or ethical conflict, nonadherence, or emotional distress.

Cultural desire, awareness, sensitivity, and knowledge are the building blocks for developing cultural skill. Cultural skill is reflected by the nurse’s ability to gather and synthesize relevant cultural information about their patients while planning care and using culturally sensitive communication skills. Nurses with cultural skill provide care consistent with their patients’ cultural needs and deliberately take steps to secure a safe health care environment that is free of discrimination or intolerance. For example, a culturally skilled nurse will make space and seating available within a patient’s hospital room for accompanying family members when this support is valued by the patient.[86]

Cultural encounters is a process where the nurse directly engages in face-to-face cultural interactions and other types of encounters with clients from culturally diverse backgrounds in order to modify existing beliefs about a cultural group and to prevent possible stereotyping.

By developing the characteristics of cultural awareness, cultural knowledge, cultural skill, and cultural encounters, a nurse develops cultural competence.

The freedom to express one’s cultural beliefs is a fundamental right of all people. Nurses realize that people speak, behave, and act in many different ways due to the influential role that culture plays in their lives and their view of the world. Cultural competence is a lifelong process of applying evidence-based nursing in agreement with the cultural values, beliefs, worldview, and practices of patients to produce improved patient outcomes.[87],[88],[89]

Culturally-competent care requires nurses to combine their knowledge and skills with awareness, curiosity, and sensitivity about their patients’ cultural beliefs. It takes motivation, time, and practice to develop cultural competence, and it will evolve throughout your nursing career. Culturally competent nurses have the power to improve the quality of care leading to better health outcomes for culturally diverse patients. Nurses who accept and uphold the cultural values and beliefs of their patients are more likely to develop supportive and trusting relationships with their patients. In turn, this opens the way for optimal disease and injury prevention and leads towards positive health outcomes for all patients .

The roots of providing culturally-competent care are based on the original transcultural nursing theory developed by Dr. Madeleine Leininger. Transcultural nursing incorporates cultural beliefs and practices of individuals to help them maintain and regain health or to face death in a meaningful way.[90] See Figure 3.4[91] for an image of Dr. Leininger. Read more about transcultural nursing theory in the following box.

Madeleine Leininger and the Transcultural Nursing Theory[92]

Dr. Madeleine Leininger (1925-2012) founded the transcultural nursing theory. She was the first professional nurse to obtain a PhD in anthropology. She combined the "culture" concept from anthropology with the "care" concept from nursing and reformulated these concepts into "culture care."