Communication

2.3 Communicating with Patients

Therapeutic communication is a type of professional communication used by nurses with patients and defined as, “The purposeful, interpersonal information-transmitting process through words and behaviors based on both parties’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills, which leads to patient understanding and participation.”[1] Therapeutic communication techniques used by nurses have roots going back to Florence Nightingale, who insisted on the importance of building trusting relationships with patients and believed in the therapeutic healing that resulted from nurses’ presence with patients.[2] Since then, several professional nursing associations have highlighted therapeutic communication as one of the most vital elements in nursing.

Read an example of a nursing student effectively using therapeutic communication with patients in the following box.

An Example of Nursing Student Using Therapeutic Communication

Ms. Z. is a nursing student who enjoys interacting with patients. When she goes to patients’ rooms, she greets them and introduces herself and her role in a calm tone. She kindly asks patients about their problems and notices their reactions. She does her best to solve their problems and answer their questions. Patients perceive that she wants to help them. She treats patients professionally by respecting boundaries and listening to them in a nonjudgmental manner. She addresses communication barriers and respects patients’ cultural beliefs. She notices patients’ health literacy and ensures they understand her messages and patient education. As a result, patients trust her and feel as if she cares about them, so they feel comfortable sharing their health care needs with her.[3],[4]

Active Listening and Attending Behaviors

Listening is obviously an important part of communication. There are three main types of listening: competitive, passive, and active. Competitive listening happens when we are focused on sharing our own point of view instead of listening to someone else. Passive listening occurs when we are not interested in listening to the other person and we assume we understand what the person is communicating correctly without verifying. During active listening, we are communicating verbally and nonverbally that we are interested in what the other person is saying while also actively verifying our understanding with the speaker. For example, an active listening technique is to restate what the person said and then verify our understanding is correct. This feedback process is the main difference between passive listening and active listening.[5]

Touch

Touch is a powerful way to professionally communicate caring and empathy if done respectfully while being aware of the patient’s cultural beliefs. Nurses commonly use professional touch when assessing, expressing concern, or comforting patients. For example, simply holding a patient’s hand during a painful procedure can be very effective in providing comfort. See Figure 2.7[6] for an image of a nurse using touch as a therapeutic technique when caring for a patient.

Therapeutic Techniques

Therapeutic communication techniques are specific methods used to provide patients with support and information while focusing on their concerns. Nurses assist patients to set goals and select strategies for their plan of care based on their needs, values, skills, and abilities. It is important to recognize the autonomy of the patient to make their own decisions, maintain a nonjudgmental attitude, and avoid interrupting. Depending on the developmental stage and educational needs of the patient, appropriate terminology should be used to promote patient understanding and rapport. When using therapeutic communication, nurses often ask open-ended statements and questions, repeat information, or use silence to prompt patients to work through problems on their own.[7] Table 2.3a describes a variety of therapeutic communication techniques.[8]

Table 2.3a Therapeutic Communication Techniques

| Therapeutic Technique | Description |

|---|---|

| Active Listening | By using nonverbal and verbal cues such as nodding and saying “I see,” nurses can encourage patients to continue talking. Active listening involves showing interest in what patients have to say, acknowledging that you’re listening and understanding, and engaging with them throughout the conversation. Nurses can offer general leads such as “What happened next?” to guide the conversation or propel it forward. |

| Using Silence | At times, it’s useful to not speak at all. Deliberate silence can give both nurses and patients an opportunity to think through and process what comes next in the conversation. It may give patients the time and space they need to broach a new topic. |

| Accepting | Sometimes it is important to acknowledge a patient’s message and affirm that they’ve been heard. Acceptance isn’t necessarily the same thing as agreement; it can be enough to simply make eye contact and say, “Yes, I hear what you are saying.” Patients who feel their nurses are listening to them and taking them seriously are more likely to be receptive to care. |

| Giving Recognition | Recognition acknowledges a patient’s behavior and highlights it. For example, saying something such as “I noticed you took all of your medications today” draws attention to the action and encourages it. |

| Offering Self | Hospital stays can be lonely and stressful at times. When nurses are present with their patients, it shows patients they value them and are willing to give them time and attention. Offering to simply sit with patients for a few minutes is a powerful way to create a caring connection. |

| Giving Broad Openings/Open-Ended Questions | Therapeutic communication is often most effective when patients direct the flow of conversation and decide what to talk about. To that end, giving patients a broad opening such as “What’s on your mind today?” or “What would you like to talk about?” can be a good way to allow patients an opportunity to discuss what’s on their mind. |

| Seeking Clarification | Similar to active listening, asking patients for clarification when they say something confusing or ambiguous is important. Saying something such as “I’m not sure I understand. Can you explain it to me?” helps nurses ensure they understand what’s actually being said and can help patients process their ideas more thoroughly. |

| Placing the Event in Time or Sequence | Asking questions about when certain events occurred in relation to other events can help patients (and nurses) get a clearer sense of the whole picture. It forces patients to think about the sequence of events and may prompt them to remember something they otherwise wouldn’t. |

| Making Observations | Observations about the appearance, demeanor, or behavior of patients can help draw attention to areas that may indicate a problem. Observing that they look tired may prompt patients to explain why they haven’t been getting much sleep lately, or making an observation that they haven’t been eating much may lead to the discovery of a new symptom. |

| Encouraging Descriptions of Perception | For patients experiencing sensory issues or hallucinations, it can be helpful to ask about these perceptions in an encouraging, nonjudgmental way. Phrases such as “What do you hear now?” or “What does that look like to you?” give patients a prompt to explain what they’re perceiving without casting their perceptions in a negative light. |

| Encouraging Comparisons | Patients often draw upon previous experiences to deal with current problems. By encouraging them to make comparisons to situations they have coped with before, nurses can help patients discover solutions to their problems. |

| Summarizing | It is often useful to summarize what patients have said. This demonstrates to patients that the nurse was listening and allows the nurse to verify information. Ending a summary with a phrase such as “Does that sound correct?” gives patients explicit permission to make corrections if they’re necessary. |

| Reflecting | Patients often ask nurses for advice about what they should do about particular problems. Nurses can ask patients what they think they should do, which encourages them to be accountable for their own actions and helps them come up with solutions themselves. |

| Focusing | Sometimes during a conversation, patients mention something particularly important. When this happens, nurses can focus on their statement, prompting patients to discuss it further. Patients don’t always have an objective perspective on what is relevant to their case, but as impartial observers, nurses can more easily pick out the topics on which to focus. |

| Confronting | Nurses should only apply this technique after they have established trust. In some situations, it can be vital to the care of patients to disagree with them, present them with reality, or challenge their assumptions. Confrontation, when used correctly, can help patients break destructive routines or understand the state of their current situation. |

| Voicing Doubt | Voicing doubt can be a gentler way to call attention to incorrect or delusional ideas and perceptions of patients. By expressing doubt, nurses can force patients to examine their assumptions. |

| Offering Hope and Humor | Because hospitals can be stressful places for patients, sharing hope that they can persevere through their current situation and lightening the mood with humor can help nurses establish rapport quickly. This technique can keep patients in a more positive state of mind. However, it is important to tailor humor to the patient’s sense of humor. |

In addition to the therapeutic techniques listed in Table 2.3a, nurses and nursing students should genuinely communicate with empathy. Communicating honestly, genuinely, and authentically is powerful. It opens the door to creating true connections with others.[9] Communicating with empathy has also been described as providing “unconditional positive regard.” Research has demonstrated that when health care teams communicate with empathy, there is improved patient healing, reduced symptoms of depression, and decreased medical errors.[10]

Nurses and nursing students must be aware of potential barriers to communication. In addition to considering common communication barriers discussed in the previous section, there are several nontherapeutic responses to avoid. These responses often block the patient’s communication of their feelings or ideas. See Table 2.3b for a description of nontherapeutic responses.[11]

Table 2.3b Nontherapeutic Responses

| Nontherapeutic Response | Description |

|---|---|

| Asking Personal Questions | Asking personal questions that are not relevant to the situation is not professional or appropriate. Don’t ask questions just to satisfy your curiosity. For example, asking, “Why have you and Mary never married?” is not appropriate. A more therapeutic question would be, “How would you describe your relationship with Mary?” |

| Giving Personal Opinions | Giving personal opinions takes away the decision-making from the patient. Effective problem-solving must be accomplished by the patient and not the nurse. For example, stating, “If I were you, I’d put your father in a nursing home” is not therapeutic. Instead, it is more therapeutic to say, “Let’s talk about what options are available to your father.” |

| Changing the Subject | Changing the subject when someone is trying to communicate with you demonstrates lack of empathy and blocks further communication. It seems to say that you don’t care about what they are sharing. For example, stating, “Let’s not talk about your insurance problems; it’s time for your walk now” is not therapeutic. A more therapeutic response would be, “After your walk, let’s talk some more about what’s going on with your insurance company.” |

| Stating Generalizations and Stereotypes | Generalizations and stereotypes can threaten nurse-patient relationships. For example, it is not therapeutic to state the stereotype, “Older adults are always confused.” It is better to focus on the patient’s concern and ask, “Tell me more about your concerns about your father’s confusion.” |

| Providing False Reassurances | When a patient is seriously ill or distressed, the nurse may be tempted to offer hope with statements such as “You’ll be fine,” or “Don’t worry; everything will be alright.” These comments tend to discourage further expressions of feelings by the patient. A more therapeutic response would be, “It must be difficult not to know what the surgeon will find. What can I do to help?” |

| Showing Sympathy | Sympathy focuses on the nurse’s feelings rather than the patient. Saying “I’m so sorry about your amputation; I can’t imagine losing a leg.” This statement shows pity rather than trying to help the patient cope with the situation. A more therapeutic response would be, “The loss of your leg is a major change; how do you think this will affect your life?” |

| Asking “Why” Questions | A nurse may be tempted to ask the patient to explain “why” they believe, feel, or act in a certain way. However, patients and family members interpret “why” questions as accusations and become defensive. It is best to phrase a question by avoiding the word “why.” For example, instead of asking, “Why are you so upset?” it is better to rephrase the statement as, “You seem upset. What’s on your mind?” |

| Approving or Disapproving | Nurses should not impose their own attitudes, values, beliefs, and moral standards on others while in the professional nursing role. Judgmental messages contain terms such as “should,” “shouldn’t,” “ought to,” “good,” “bad,” “right,” or “wrong.” Agreeing or disagreeing sends the subtle message that nurses have the right to make value judgments about the patient’s decisions. Approving implies that the behavior being praised is the only acceptable one, and disapproving implies that the patient must meet the nurse’s expectations or standards. Instead, the nurse should help the patient explore their own beliefs and decisions. For example, it is nontherapeutic to state, “You shouldn’t consider elective surgery; there are too many risks involved.” A more therapeutic response would be, “So you are considering elective surgery. Tell me more about it…” gives the patient a chance to express their ideas or feelings without fear of being judged. |

| Giving Defensive Responses | When patients or family members express criticism, nurses should listen to what they are saying. Listening does not imply agreement. To discover reasons for the patient’s anger or dissatisfaction, the nurse should listen without criticism, avoid being defensive or accusatory, and attempt to defuse anger. For example, it is not therapeutic to state, “No one here would intentionally lie to you.” Instead, a more therapeutic response would be, “You believe people have been dishonest with you. Tell me more about what happened.” (After obtaining additional information, the nurse may elect to follow the chain of command at the agency and report the patient’s concerns for follow-up.) |

| Providing Passive or Aggressive Responses | Passive responses serve to avoid conflict or sidestep issues, whereas aggressive responses provoke confrontation. Nurses should use assertive communication as described in the “Basic Communication Concepts” section. |

| Arguing | Challenging or arguing against patient perceptions denies that they are real and valid to the other person. They imply that the other person is lying, misinformed, or uneducated. The skillful nurse can provide information or present reality in a way that avoids argument. For example, it is not therapeutic to state, “How can you say you didn’t sleep a wink when I heard you snoring all night long!” A more therapeutic response would be, “You don’t feel rested this morning? Let’s talk about ways to improve your rest.” |

Strategies for Effective Communication

In addition to using therapeutic communication techniques, avoiding nontherapeutic responses, and overcoming common barriers to communication, there are additional strategies for promoting effective communication when providing patient-centered care. Specific questions to ask patients are as follows:

- What concerns do you have about your plan of care?

- What questions do you have about your medications?

- Did I answer your question(s) clearly or is there additional information you would like?[12]

Listen closely for feedback from patients. Feedback provides an opportunity to improve patient understanding, improve the patient-care experience, and provide high-quality care. Other suggestions for effective communication with hospitalized patients include the following:

- Round with the providers and read progress notes from other health care team members to ensure you have the most up-to-date information about the patient’s treatment plan and progress. This information helps you to provide safe patient care as changes occur and also to accurately answer the patient’s questions.

- Review information periodically with the patient to improve understanding.

- Use patient communication boards in their room to set goals and communicate important reminders with the patient, family members, and other health care team members. This strategy can reduce call light usage for questions related to diet and activity orders and also gives patients and families the feeling that they always know the current plan of care. However, keep patient confidentiality in mind regarding information to publicly share on the board that visitors may see.

- Provide printed information on medical procedures, conditions, and medications. It helps patients and family members to have multiple ways to provide information.[13]

Adapting Your Communication

When communicating with patients and family members, take note of your audience and adapt your message based on their characteristics such as age, developmental level, cognitive abilities, and any communication disorders. For patients with language differences, it is vital to provide trained medical interpreters when important information is communicated.

Adapting communication according to the patient’s age and developmental level includes the following strategies:

- When communicating with children, speak calmly and gently. It is often helpful to demonstrate what will be done during a procedure on a doll or stuffed animal. To establish trust, try using play or drawing pictures.

- When communicating with adolescents, give freedom to make choices within established limits.

- When communicating with older adults, be aware of potential vision and hearing impairments that commonly occur and address these barriers accordingly. For example, if a patient has glasses and/or hearing aids, be sure these devices are in place before communicating. See the following box for evidence-based strategies for communication with patients who have impaired hearing and vision.[14]

Strategies for Communicating with Patients with Impaired Hearing and Vision

Impaired Hearing

- Gain the patient’s attention before speaking (e.g., through touch)

- Minimize background noise

- Position yourself 2-3 feet away from the patient

- Facilitate lip-reading by facing the patient directly in a well-lit environment

- Use gestures, when necessary

- Listen attentively, allowing the patient adequate time to process communication and respond

- Refrain from shouting at the patient

- Ask the patient to suggest strategies for improved communication (e.g., speaking toward better ear and moving to well-lit area)

- Face the patient directly, establish eye contact, and avoid turning away mid sentence

- Simplify language (i.e., do not use slang but do use short, simple sentences), as appropriate

- Note and document the patient’s preferred method of communication (e.g., verbal, written, lip-reading, or American Sign Language) in plan of care

- Assist the patient in acquiring a hearing aid or assistive listening device

- Refer to the primary care provider or specialist for evaluation, treatment, and hearing rehabilitation[15]

Impaired Vision

- Identify yourself when entering the patient’s space

- Ensure the patient’s eyeglasses or contact lenses have current prescription, are cleaned, and stored properly when not in use

- Provide adequate room lighting

- Minimize glare (i.e., offer sunglasses or draw window covering)

- Provide educational materials in large print

- Apply labels to frequently used items (i.e., mark medication bottles using high-contrasting colors)

- Read pertinent information to the patient

- Provide magnifying devices

- Provide referral for supportive services (e.g., social, occupational, and psychological)[16]

Patients with communication disorders require additional strategies to ensure effective communication. For example, aphasia is a communication disorder that results from damage to portions of the brain that are responsible for language. Aphasia usually occurs suddenly, often following a stroke or head injury, and impairs the patient’s expression and understanding of language. Global aphasia is caused by injuries to multiple language-processing areas of the brain, including those known as Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas. These brain areas are particularly important for understanding spoken language, accessing vocabulary, using grammar, and producing words and sentences. Individuals with global aphasia may be unable to say even a few words or may repeat the same words or phrases over and over again. They may have trouble understanding even simple words and sentences.[17]

The most common type of aphasia is Broca's aphasia. People with Broca’s aphasia often understand speech and know what they want to say, but frequently speak in short phrases that are produced with great effort. For example, they may intend to say, “I would like to go to the bathroom,” but instead the words, “Bathroom, Go,” are expressed. They are often aware of their difficulties and can become easily frustrated. See the hyperlink in the box below for evidence-based strategies to enhance communication with a person with impaired speech.[18]

Strategies to Improve Communication with Patients with Impaired Speech

- Modify the environment to minimize excess noise and decrease emotional distress

- Phrase questions so the patient can answer using a simple “Yes” or “No,” being aware that patients with expressive aphasia may provide automatic responses that are incorrect

- Monitor the patient for frustration, anger, depression, or other responses to impaired speech capabilities

- Provide alternative methods of speech communication (e.g., writing tablet, flash cards, eye blinking, communication board with pictures and letters, hand signals or gestures, and computer)

- Adjust your communication style to meet the needs of the patient (e.g., stand in front of the patient while speaking, listen attentively, present one idea or thought at a time, speak slowly but avoid shouting, use written communication, or solicit family’s assistance in understanding the patient’s speech)

- Ensure the call light is within reach and central call light system is marked to indicate the patient has difficulty with speech

- Repeat what the patient said to ensure accuracy

- Instruct the patient to speak slowly

- Collaborate with the family and a speech therapist to develop a plan for effective communication[19]

Maintaining Patient Confidentiality

When communicating with patients, their friends, their family members, and other members of the health care team, it is vital for the nurse to maintain patient confidentiality. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) provides standards for ensuring privacy of patient information that are enforceable by law. Nurses must always be aware of where and with whom they share patient information. For example, information related to patient care should not be discussed in public areas, paper charts must be kept in secure areas, computers must be logged off when walked away from, and patient information should only be shared with those directly involved in patient care. For more information about patient confidentiality, see the “Legal Considerations & Ethics” section in the “Scope of Practice” chapter.

Read more information about the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA).

- Abdolrahimi, M., Ghiyasvandian, S., Zakerimoghadam, M., & Ebadi, A. (2017). Therapeutic communication in nursing students: A Walker & Avant concept analysis. Electronic Physician, 9(8), 4968–4977. https://doi.org/10.19082/4968 ↵

- Karimi, H., & Masoudi Alavi, N. (2015). Florence Nightingale: The mother of nursing. Nursing and Midwifery Studies, 4(2), e29475. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4557413/. ↵

- Abdolrahimi, M., Ghiyasvandian, S., Zakerimoghadam, M., & Ebadi, A. (2017). Therapeutic communication in nursing students: A Walker & Avant concept analysis. Electronic Physician, 9(8), 4968–4977. https://doi.org/10.19082/4968 ↵

- “beautiful african nurse taking care of senior patient in wheelchair” by agilemktg1 is in the Public Domain ↵

- This work is a derivative of Human Relations by LibreTexts and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ↵

- Flickr - Official U.S. Navy Imagery - A nurse examines a newborn baby..jpg” by MC2 John O'Neill Herrera/U.S. Navy is in the Public Domain ↵

- American Nurse. (n.d.). Therapeutic communication techniques. https://www.myamericannurse.com/therapeutic-communication-techniques/ ↵

- American Nurse. (n.d.). Therapeutic communication techniques. https://www.myamericannurse.com/therapeutic-communication-techniques/ ↵

- Balchan, M. (2016). The Magic of Genuine Communication. http://michaelbalchan.com/communication/ ↵

- Morrison, E. (2019). Empathetic Communication in Healthcare. https://www.cibhs.org/sites/main/files/file-attachments/empathic_communication_in_healthcare_workbook.pdf?1594162691 ↵

- Burke, A. (2021). Therapeutic Communication: NCLEX-RN. https://www.registerednursing.org/nclex/therapeutic-communication/ ↵

- Smith, L. L. (2018, June 12). Strategies for effective patient communication. American Nurse. https://www.myamericannurse.com/strategies-for-effective-patient-communication/ ↵

- Smith, L. L. (2018, June 12). Strategies for effective patient communication. American Nurse. https://www.myamericannurse.com/strategies-for-effective-patient-communication/ ↵

- Butcher, H., Bulechek, G., Dochterman, J., & Wagner, C. (2018). Nursing interventions classification (NIC). Elsevier, pp. 115-116 ↵

- Butcher, H., Bulechek, G., Dochterman, J., & Wagner, C. (2018). Nursing interventions classification (NIC). Elsevier, pp. 115-116 ↵

- Butcher, H., Bulechek, G., Dochterman, J., & Wagner, C. (2018). Nursing interventions classification (NIC). Elsevier, pp. 115-116 ↵

- National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD). (2017, March 6). Aphasia. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/aphasia ↵

- Butcher, H., Bulechek, G., Dochterman, J., & Wagner, C. (2018). Nursing interventions classification (NIC). Elsevier, pp. 115-116. ↵

- Butcher, H., Bulechek, G., Dochterman, J., & Wagner, C. (2018). Nursing interventions classification (NIC). Elsevier, pp. 115-116. ↵

Learning Activities

(Answers to “Learning Activities” can be found in the “Answer Key” at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

Apply the concepts you learned from this chapter to the following patient scenario[1].

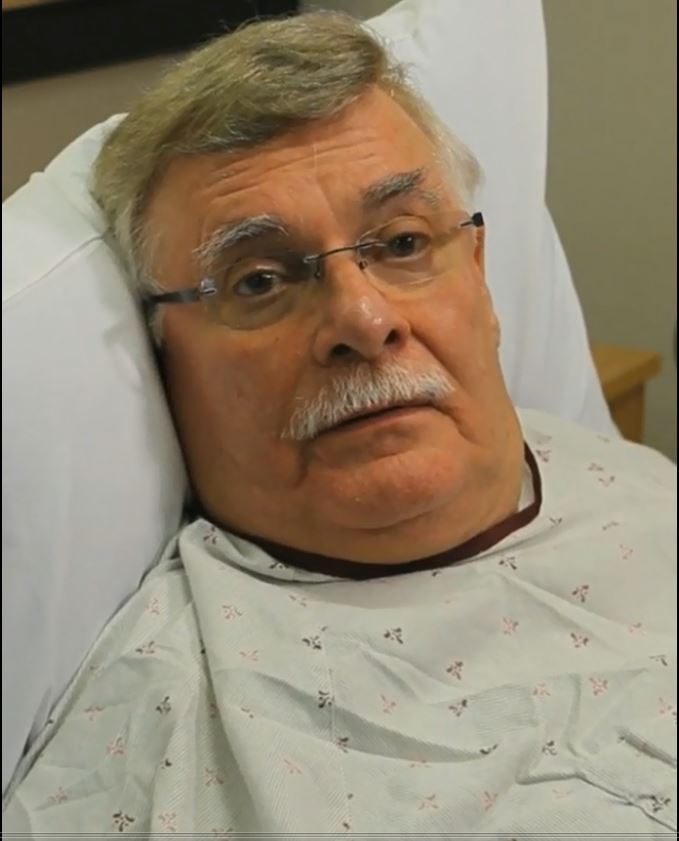

Joe is a 68-year-old male who was recently diagnosed for colon cancer last week and underwent a colon resection three days ago. See Figure 11.15 for an image of Joe.[2] In the change of shift report, you hear that he is receiving morphine by PCA pump for pain, but he is not using it very often. Staff reports he “needs much encouragement” to get out of bed and participate in self-cares. He has crackles in his lung bases and his oxygen saturation is 88% on room air.

- What additional assessments (subjective and objective) will you perform on Joe?

- List the top three priority nursing diagnoses for Joe.

- Joe states, “I don’t want to use morphine. I am afraid I will become addicted to it like my friend did after he came home from the war.” How will you respond to therapeutically address his concerns, yet also teach Joe about good pain management?

- What are common side effects of opioids and how will you plan to manage these side effects for Joe?

- Emotional issues could also be affecting Joe’s perception of pain. What will you further physically assess and therapeutically address?

- After providing patient education about morphine and the PCA pump, you check on Joe later in the day and notice he has had five self-doses every hour with 15 attempts in the past hour. The pump is set for a maximum of 6 doses per hour. What further assessments will you perform?

Assessment

Nurses play an essential role in performing comprehensive pain assessment. Assessments include asking questions about the presence of pain, as well as observing for nonverbal indicators of pain, such as grimacing, moaning, and touching the painful area. It is especially important to observe for nonverbal indicators of pain in patients unable to self-report their pain, such as infants, children, patients who have a cognitive disorder, patients at end of life, non-English speaking patients, or patients who tend to be stoic due to cultural beliefs. See Figure 11.14[3] for an image of a patient who is expressing pain nonverbally.

Recall that pain is defined as whatever the person experiencing it says it is. Subjective assessment includes asking questions regarding the severity rating, as well as obtaining comprehensive information by using the “PQRSTU” or “OLDCARTES” methods for assessing a chief complaint. For some patients who are unable to quantify the severity of their pain, a visual scale like the FACES scale is the best way to perform subjective assessment regarding the severity of pain.

Objective data includes observations of nonverbal indications of pain, such as restlessness, facial grimacing and wincing, moaning, and rubbing or guarding painful areas. For patients who cannot verbalize their pain, using a scale like the FLACC, COMFORT, or PAINAD is helpful to standardize observations across different staff members. Keep in mind that patients experiencing acute pain will also likely have vital signs changes, such as increased blood pressure, increased heart rate, and increased respiratory rate.

It is important to assess the impact of pain on a patient’s daily functioning. This can be accomplished by asking what effect the pain has on their ability to bathe, dress, prepare food, eat, walk, and complete other daily activities. Assessing the impact of pain on daily functioning is a new standard of care that assists the interdisciplinary team in tailoring treatment goals and interventions that are customized to the patient’s situation. For example, for some patients, chronic pain affects their ability to be employed, so effective pain management is vital so they can return to work. For other patients receiving palliative care, the ability to sit up and eat a meal with loved ones without pain is an important goal.[4]

When performing a patient assessment, any new complaints of pain or pain that is unresponsive to the current treatment plan should be reported to the health care provider. Instances of sudden, severe pain or chest pain require immediate notification or contact of emergency services.

Diagnoses

Commonly used NANDA-I nursing diagnoses for pain include Acute Pain (duration less than 3 months) and Chronic Pain. See Table 11.5 for more information regarding these diagnoses.[5] For more information about defining characteristics and related factors for other NANDA-I nursing diagnoses, refer to a current nursing diagnosis resource.

Table 11.5 Pain NANDA-I Nursing Diagnoses[6]

| NANDA-I Diagnosis | Definition | Defining Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Acute Pain | Unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with acute or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage; sudden or slow onset of any intensity from mild to severe with an anticipated or predictable end, and with a duration of less than 3 months. |

|

| Chronic Pain | Unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage (International Association for the Study of Pain); sudden or slow onset of any intensity from mild to severe, constant or recurring without anticipated or predictable end, and with a duration of greater than 3 months. |

|

Outcome Identification

An overall goal when providing pain management is, “The patient will report that the pain management treatment plan achieves their comfort-function goals.”[7]

SMART outcomes are customized to the patient’s unique situation. An example of a SMART goal is, “The patient will notify the nurse promptly for pain intensity level that is greater than their comfort-function goal throughout shift.”[8]

Planning Interventions

Several pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions have been described throughout this chapter. See the following box for a summarized list of interventions for acute pain management.

Acute Pain Management[9]

- Identify pain intensity during required recovery activities (e.g., coughing and deep breathing, ambulation, transfers to chair, etc.)

- Explore patient’s knowledge and beliefs about pain, including cultural influences

- Question patient regarding the level of pain that allows a state of comfort and desired function and attempt to keep pain at or lower than identified level

- Ensure that the patient receives prompt analgesic care before the pain becomes severe or before pain-inducing activities

- Administer analgesics around-the-clock as needed the first 24 to 48 hours after surgery, trauma, or injury except if sedation or respiratory status indicates otherwise

- Monitor sedation and respiratory status before administering opioids and at regular intervals when opioids are administered

- Follow agency protocols in selecting analgesia and dosage

- Use a combination of prescribed medications (e.g., opioids, nonopioids, and adjuvants), if pain level is severe

- Select and implement interventions tailored to the patient’s risks, benefits, and preferences (e.g., pharmacological and nonpharmacological) to facilitate pain relief

- Cautiously use analgesics that may have adverse effects in older adults

- Administer analgesics using the least invasive route available, avoiding the intramuscular route

- Advocate PCA, intrathecal, and epidural routes of administration when appropriate

- Modify pain control measures on the basis of the patient’s response to treatment

- Prevent and/or manage medication side effects

- Notify prescribing provider if pain control measures are unsuccessful

- Provide accurate information to family members or caregivers about the patient’s pain experience with the patient's permission

See the following box for a summarized list of interventions for chronic pain management.

Chronic Pain Management[10]

- Explore the patient’s knowledge and beliefs about pain, including cultural influences

- Determine the pain experience on quality of life (e.g., sleep, appetite, activity, cognition, mood, relationships, job performance, and role responsibilities)

- Evaluate the effectiveness of past pain control measures with the patient

- Question the patient regarding the level of pain that allows a state of comfort and appropriate functioning and attempt to keep pain at or lower than identified level

- Control environmental factors that may influence the patient’s pain experience

- Ensure that the patient receives prompt analgesic care before the pain becomes severe or before activities that are anticipated to be pain-inducing

- Select and implement intervention options tailored to the patient’s risks, benefits, and preferences (e.g., pharmacological, nonpharmacological, interpersonal) to facilitate pain relief, as appropriate

- Instruct the patient and family about principles of pain management

- Encourage the patient to monitor own pain and to use self-management approaches

- Encourage appropriate use of nonpharmacological techniques (e.g., biofeedback, TENS, hypnosis, relaxation, guided imagery, music therapy, distraction, play therapy, activity therapy, acupressure, heat and cold application, and massage) and pharmacological options as pain control measures

- Avoid use of analgesics that may have adverse effects on older adults

- Collaborate with the patient, family, and other health professionals to select and implement pain control measures

- Prevent or manage side effects

- Evaluate the effectiveness of pain control measures through ongoing monitoring of the pain experience

- Watch for signs of depression (e.g., sleeplessness, not eating, flat affect, statements of depression, or suicidal ideation)

- Watch for signs of anxiety or fear (e.g., irritability, tension, worry, or fear of movement)

- Modify pain control measures on the basis of the patient’s response to treatment

- Incorporate the family in the pain relief modality, when possible

- Utilize a multidisciplinary approach to pain management, when appropriate

- Consider referrals for the patient and family to support groups and other resources, as appropriate

- Evaluate patient satisfaction with pain management at specified intervals

- Evaluate barriers to adherence with past pain management care plans

Implementing Pharmacological Interventions

Patients should be involved and engaged in their plan of care to treat pain. By demonstrating empathy and collaborating with patients and the interdisciplinary team, it is more likely the treatment plan will be effective based on the patient’s goals.

When administering analgesic medication, holistic nursing care is important. Begin by considering the patient’s goals for pain relief and ask if they have been met effectively by previously administered medications. If they have not been met, it may be necessary to advocate for additional or alternative medication with the health care provider. It is also important to consider if the patient is experiencing any side effects that may impact the patient’s desire to take additional pain medication.

When administering medications that have been ordered on an “as-needed” basis, it is vital for the nurse to verify the amount of medication the patient received in the past 24 hours and if any dosage limits have been met to ensure patient safety.

Prior to administration, consider the best route of administration for this patient at this particular time. For example, if the patient is nauseated and vomiting, then an oral route may not be effective. On the other hand, if a patient’s pain has improved when receiving intravenous medications during the recovery process, it may be possible for the patient to begin taking oral pain medications in preparation for discharge home. Keep the WHO ladder in mind when selecting medications to reach patient goals while also avoiding potential adverse effects when possible.

When preparing opioid medications, it is important to remember that these medications are controlled substances with special regulations regarding storage, count auditing, and disposal/wasting of medication. Follow agency policy regarding these issues. It is also important to assess the patient’s level of sedation and respiratory status before administering additional doses of opioids and withhold the medication if the patient is oversedated or their respiratory rate is less than 12/minute. However, when providing pain management during end-of-life care, these parameters no longer apply because the emphasis is on providing comfort according to the patient’s preferences. Read more about end-of-life care in the “Grief and Loss” chapter.

Evaluation

It is vital for the nurse to regularly evaluate if the established interventions are effectively meeting the pain management and function goals established collaboratively with the patient. Additionally, when administering analgesics, the patient should be reassessed in an hour (or other time frame based on the onset and peak of the medication) to determine if the medication was effective. If interventions are not effective, then follow-up interventions are required, which may include contacting the health care provider.

For patients living with chronic pain, it can be helpful for them or their caregiver to maintain a pain journal. In the journal they can document activities that precipitated pain, medications taken to manage the pain, and whether these medications were effective in helping them to meet their functional goals. This journal is shared with the health care provider during follow-up visits to enhance the treatment plan.[11]

The nurse must continually monitor for potential adverse effects of pain medications. For example, if a patient is receiving acetaminophen daily for chronic osteoarthritis pain, signs of liver dysfunction, such as jaundice and elevated liver function bloodwork, should be monitored. For older adults receiving NSAIDs, it is important to watch for early signs of gastrointestinal bleeding, such as melena. Patients receiving opioids should be continually monitored for oversedation, respiratory depression, constipation, nausea and vomiting, urinary retention, and pruritus. Side effects should be reported to the health care provider and orders received for treatment.

Acute pain: Pain that is limited in duration and is associated with a specific cause.

Addiction: A chronic disease of the brain’s reward, motivation, memory, and related circuitry reflected in an individual pathologically pursuing reward and/or relief by substance use and other behaviors. Addiction is characterized by several symptoms, such as the inability to consistently abstain from a substance, impaired behavioral control, cravings, diminished recognition of significant problems with one’s behaviors and interpersonal relationships, and a dysfunctional emotional response.

Adjuvant: Medication that is not classified as an analgesic but has been found in clinical practice to have either an independent analgesic effect or additive analgesic properties when administered with opioids.

Analgesics: Medications used to relieve pain.

Chronic pain: Pain that is ongoing and persistent for longer than six months.

Misuse: Taking prescription pain medications in a manner or dose other than prescribed; taking someone else’s prescription, even if for a medical complaint such as pain; or taking a medication to feel euphoria (i.e., to get high).

Neuropathic pain: Pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system that is typically described by patients as “burning” or “like pins and needles.”

Nociceptor: A sensory receptor for painful stimuli.

Pain: An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage.

Patient-Controlled Analgesia (PCA): A method of pain management that allows hospitalized patients with severe pain to safely self-administer opioid medications using a programmed pump according to their level of discomfort.

Physical dependence: Withdrawal symptoms that occur when chronic pain medication is suddenly reduced or stopped because of physiological adaptations that occur from chronic exposure to the medication.

Referred pain: Pain perceived at a location other than the site of the painful stimulus. For example, pain from retained gas in the colon can cause pain to be perceived in the shoulder.

Substance abuse disorder: Significant impairment or distress from a pattern of substance use (i.e., alcohol, drugs or misuse of prescription medications).

Tolerance: A reduced response to pain medication when the same dose of a drug has been given repeatedly, requiring a higher dose of the drug to achieve the same level of response.

Learning Objectives

- Assess factors that put patients at risk for problems with sleep

- Identify factors related to sleep/rest across the life span

- Recognize characteristics of sleep deprivation

- Consider the use of nonpharmacological measures to promote sleep and rest

- Identify evidence-based practices

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs indicates sleep as one of our physiological requirements. Getting enough quality sleep at the right times according to our circadian rhythms can protect mental and physical health, safety, and quality of life. Conversely, chronic sleep deficiency increases the risk of heart disease, kidney disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, and stroke, as well as weakening the immune system.[12] This chapter will review the physiology of sleep and common sleep disorders, as well as interventions to promote good sleep.