Oxygenation

8.2 Oxygenation Basic Concepts

Several body systems contribute to a person’s oxygenation status, including the respiratory, cardiovascular, and hematological systems. These systems are reviewed in the following sections.

Respiratory System

The main function of our respiratory system is to provide the body with a constant supply of oxygen and to remove carbon dioxide. To achieve these functions, muscles and structures of the thorax create the mechanical movement of air into and out of the lungs called ventilation. Gas exchange occurs at the alveolar level where blood is oxygenated and carbon dioxide is removed, which is called respiration. Several respiratory conditions can affect a patient’s ability to maintain adequate ventilation and respiration, and there are several medications used to enhance a patient’s oxygenation status. Use the following hyperlinks to review information regarding the anatomy and physiology of the respiratory system, common respiratory conditions, and classes of respiratory medications.

Read additional information about the “Respiratory System” in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology or use the following hyperlinks to go to specific subsections of the chapter:

-

- Review the anatomy and physiology of the respiratory system.

- Learn about common respiratory disorders.

- Read about common respiratory medications

.

Cardiovascular System

In order for oxygenated blood to move from the alveoli in the lungs to the various organs and tissues of the body, the heart must adequately pump blood through the systemic arteries. The amount of blood that the heart pumps in one minute is referred to as cardiac output. The passage of blood through arteries to an organ or tissue is referred to as perfusion. Several cardiac conditions can adversely affect cardiac output and perfusion in the body. There are several medications used to enhance a patient’s cardiac output and maintain adequate perfusion to organs and tissues throughout the body. Use the following hyperlinks to review information regarding the anatomy and physiology of the cardiovascular system, common cardiac disorders, and various cardiovascular system medications.

Read additional information about the cardiovascular system in the “Cardiovascular & Renal” chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology or use the following hyperlinks to go to specific subsections of this chapter:

- Review the anatomy and physiology of the cardiovascular system.

- Learn about common cardiac disorders.

- Read about common cardiovascular system medications.

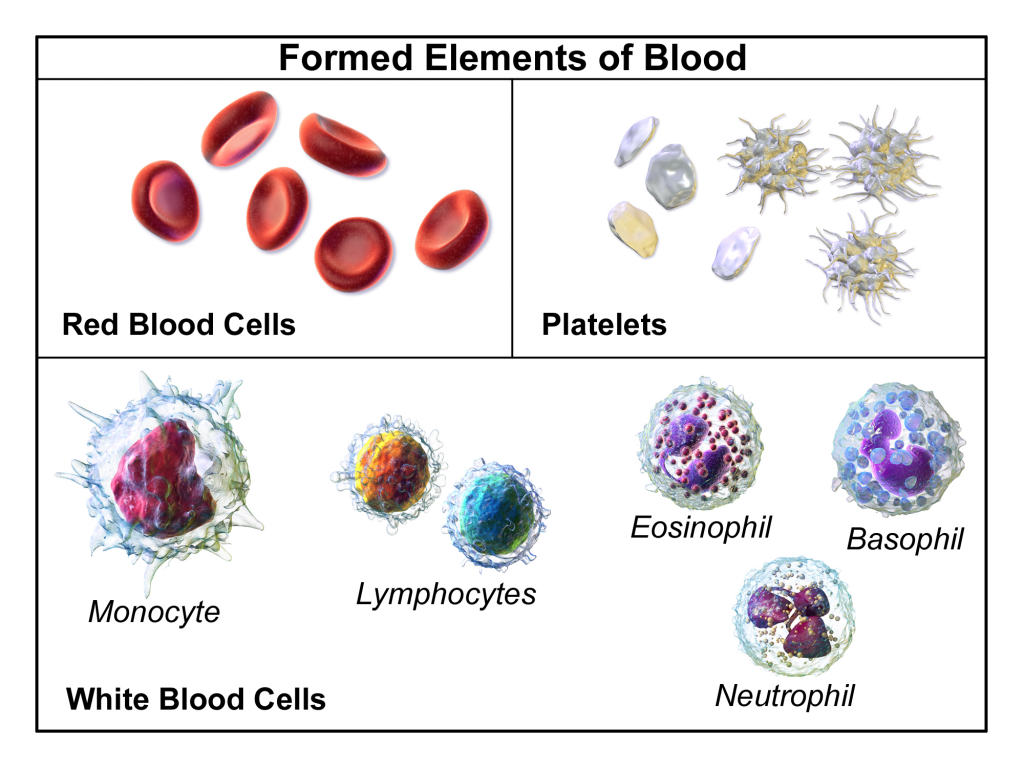

Hematological System

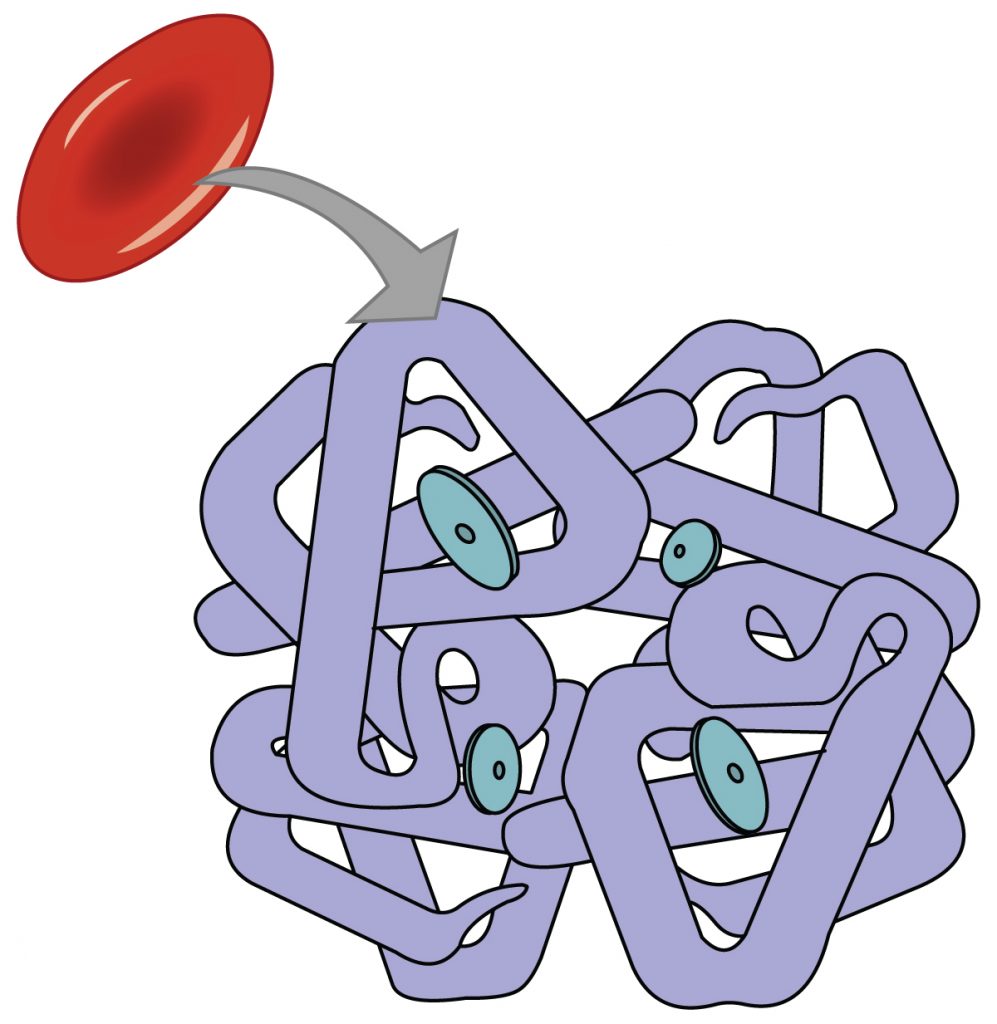

Although the bloodstream carries small amounts of dissolved oxygen, the majority of oxygen molecules are transported throughout the body by attaching to hemoglobin within red blood cells. Each hemoglobin protein is capable of carrying four oxygen molecules. When all four hemoglobin structures contain an oxygen molecule, it is referred to as “saturated.”[1] See Figure 8.1[2] for an image of hemoglobin protein within a red blood cell with four sites for carrying oxygen molecules.

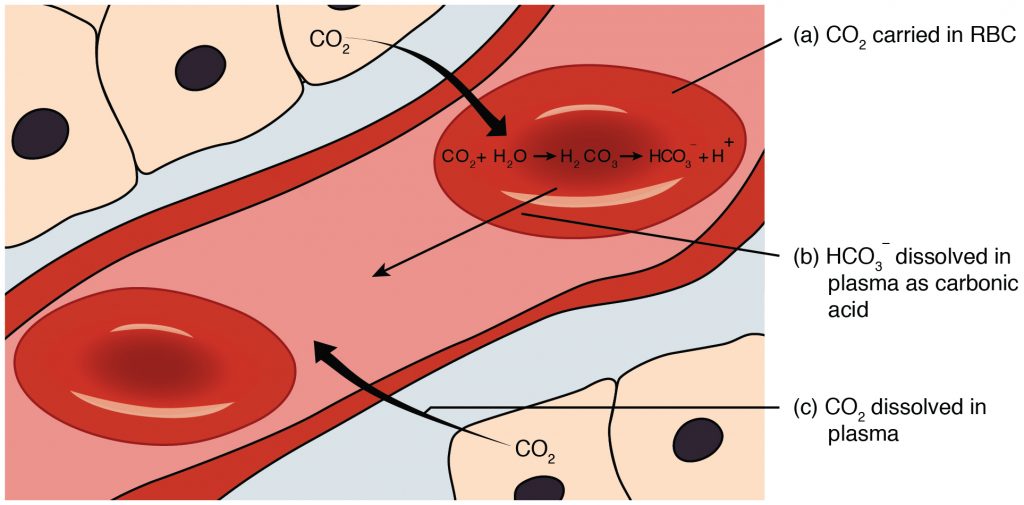

When oxygenated blood reaches tissues within the body, oxygen is released from the hemoglobin, and carbon dioxide is picked up and transported to the lungs for release on exhalation. Carbon dioxide is transported throughout the body by three major mechanisms: dissolved carbon dioxide, attachment to water as HCO3-, and attachment to the hemoglobin in red blood cells.[3] See Figure 8.2[4] for an illustration of carbon dioxide transport.[5]

Measuring Oxygen, Carbon Dioxide, and Acid Base Levels

Because the majority of oxygen transported in the blood is attached to hemoglobin, a patient’s oxygenation status is easily assessed using pulse oximetry, referred to as SpO2. See Figure 8.3[6] for an image of a pulse oximeter. This reading refers to the amount of hemoglobin that is saturated. The target range of SpO2 for an adult is 94-98%.[7] For patients with chronic oxygenation conditions such as COPD, the target range for SpO2 is often lower at 88% to 92%. Although SpO2 is an efficient, noninvasive method for assessing a patient’s oxygenation status, it is not always accurate. For example, if a patient is severely anemic, the patient has a decreased amount of hemoglobin in the blood available to carry the oxygen, which subsequently affects the SpO2 reading. Decreased perfusion of the extremities can also cause inaccurate SpO2 levels because less blood delivered to the tissues causes a false low SpO2. Additionally, other substances can attach to hemoglobin such as carbon monoxide, causing a falsely elevated SpO2.

A more specific measurement of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood is obtained using an arterial blood gas (ABG). ABG results are often used for patients who have deteriorating or unstable respiratory status requiring emergency treatment. An ABG is a blood sample that is typically drawn from the radial artery by a respiratory therapist. ABG results indicate oxygen, carbon dioxide, pH, and bicarbonate levels. The partial pressure of oxygen in the arterial blood is referred to as PaO2. PaO2 measures the pressure of oxygen dissolved in the arterial blood and how well oxygen is able to move from the lungs into the blood. The normal PaO2 level of a healthy adult is 80 to 100 mmHg. The PaO2 reading is more accurate than a SpO2 reading because it is not affected by hemoglobin levels. The partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the arterial blood is the PaCO2 level. The PaCO2 level measures the pressure of carbon dioxide dissolved in the blood and how well carbon dioxide is able to move out of the body. It is typically used to determine if sufficient ventilation is occurring at the alveolar level. The normal PaCO2 level of a healthy adult is 35-45 mmHg. The normal range of pH level for arterial blood is 7.35-7.45, and the normal range for the bicarbonate (HCO3-) level is 22-26. The SaO2 level is also calculated in ABG results, which is the calculated arterial oxygen saturation level.[8]

Hypoxia and Hypercapnia

Hypoxia is defined as a reduced level of tissue oxygenation. Hypoxia has many causes, ranging from respiratory and cardiac conditions to anemia. Hypoxemia is a specific type of hypoxia that is defined as decreased partial pressure of oxygen in the blood (PaO2) indicated in an arterial blood gas (ABG) result.

Early signs of hypoxia are anxiety, confusion, and restlessness. As hypoxia worsens, the patient’s level of consciousness and vital signs will worsen with an increased respiratory rate and heart rate and decreased pulse oximetry readings. Late signs of hypoxia include bluish discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes called cyanosis. See Figure 8.4[9] for an image of cyanosis.

Hypercapnia, also referred to as hypercarbia, is an elevated level of carbon dioxide in the blood. This level is measured by the PaCO2 level in an ABG test and is indicated when the PaCO2 level is greater than 45. Hypercapnia is caused by hypoventilation or when the alveoli are ventilated but not perfused. In a state of hypercapnia, the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the blood causes the pH of the blood to drop, leading to a state of respiratory acidosis. You can read more about respiratory acidosis in the “Acid-Base Balance” section of the “Fluids and Electrolytes” chapter. Patients with hypercapnia have symptoms such as tachycardia, dyspnea, flushed skin, confusion, headaches, and dizziness. If the hypercapnia develops gradually over time, symptoms may be mild or may not be present at all. Hypercapnia is managed by addressing its underlying cause. A noninvasive positive pressure device such as a BiPAP may be used to help eliminate the excess carbon dioxide, but if this is not sufficient, intubation may be required.[10] You can read more about BiPAP devices and intubation in the “Oxygen Therapy” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills.

It is important for a nurse to recognize early signs of respiratory distress and report changes in patient condition to prevent respiratory failure. See Table 8.2a for symptoms and signs of respiratory distress.[11]

Table 8.2a Symptoms and Signs of Respiratory Distress

| Signs and Symptoms | Description |

|---|---|

| Shortness of breath (Dyspnea) | Dyspnea is a subjective symptom of not getting enough air. Depending on severity, dyspnea causes increased levels of anxiety. |

| Restlessness | An early sign of hypoxia. |

| Tachycardia | An elevated heart rate (above 100 beats per minute in adults) can be an early sign of hypoxia. |

| Tachypnea | An increased respiration rate (above 20 breaths per minute in adults) is an indication of respiratory distress. |

| Oxygen saturation level (SpO2) | Oxygen saturation levels should be above 94% for an adult without an underlying respiratory condition. |

| Use of accessory muscles | Use of neck or intercostal muscles when breathing is an indication of respiratory distress. |

| Noisy breathing | Audible noises with breathing are an indication of respiratory conditions. Further assess lung sounds with a stethoscope for adventitious sounds such as wheezing, rales, or crackles. Secretions can plug the airway, thereby decreasing the amount of oxygen available for gas exchange in the lungs. |

| Flaring of nostrils | Nasal flaring is a sign of respiratory distress, especially in infants. |

| Skin color (Cyanosis) |

Bluish changes in skin color and mucus membranes is a late sign of hypoxia. |

| Position of patient | Patients in respiratory distress often automatically sit up and lean over by resting arms on their legs, referred to as the tripod position. The tripod position enhances lung expansion. Conversely, patients who are hypoxic often feel worse dyspnea when lying flat in bed and avoid the supine position. |

| Ability of patient to speak in full sentences | Patients in respiratory distress may be unable to speak in full sentences or may need to catch their breath between sentences. |

| Confusion or change in level of consciousness (LOC) | Confusion can be an early sign of hypoxia and changing level of consciousness is a worsening sign of hypoxia. |

Treating Hypoxia and Hypercapnia

Hypoxia and/or hypercapnia are medical emergencies and should be treated promptly by calling for assistance as indicated by agency policy.

Failure to initiate oxygen therapy when needed can result in serious harm or death of the patient. Although oxygen is considered a medication that requires a prescription, oxygen therapy may be initiated without a physician’s order in emergency situations as part of the nurse’s response to the “ABCs,” a common abbreviation for airway, breathing, and circulation. Most agencies have a protocol in place that allows nurses to apply oxygen in emergency situations and obtain the necessary order at a later time.[12]

In addition to administering oxygen therapy, there are several other interventions a nurse can implement to assist an hypoxic patient. Additional interventions used to treat hypoxia in conjunction with oxygen therapy are outlined in Table 8.2b.

Table 8.2b Interventions to Manage Hypoxia

| Interventions | Additional Information |

|---|---|

| Raise the head of the bed. | Raising the head of the bed to high Fowler’s position promotes effective chest expansion and diaphragmatic descent, maximizes inhalation, and decreases the work of breathing. |

| Use tripod positioning. | Situate the patient in a tripod position. Patients who are short of breath may gain relief by sitting upright and leaning over a bedside table while in bed, which is called a three-point or tripod position. |

| Encourage enhanced breathing and coughing techniques. | Enhanced breathing and coughing techniques such as using pursed-lip breathing, coughing and deep breathing, huffing technique, incentive spirometry, and flutter valves may assist patients to clear their airway while maintaining their oxygen levels. See the “Enhanced Breathing and Coughing Techniques” section below for additional information regarding these techniques. |

| Manage oxygen therapy and equipment. | If the patient is already on supplemental oxygen, ensure the equipment is turned on, set at the required flow rate, and is properly connected to an oxygen supply source. If a portable tank is being used, check the oxygen level in the tank. Ensure the connecting oxygen tubing is not kinked, which could obstruct the flow of oxygen. Feel for the flow of oxygen from the exit ports on the oxygen equipment. In hospitals where medical air and oxygen are used, ensure the patient is connected to the oxygen flow port.

Various types of oxygenation equipment are prescribed for patients requiring oxygen therapy. Oxygenation equipment is typically managed in collaboration with a respiratory therapist in hospital settings. Equipment includes devices such as nasal cannula, masks, Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP), Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure (BiPAP), and mechanical ventilators. For more information, see the “Oxygenation Equipment” section of the “Oxygen Therapy” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills. |

| Assess the need for respiratory medications. | Pharmacological management is essential for patients with respiratory disease such as asthma, COPD, or severe allergic response. Bronchodilators effectively relax smooth muscles and open airways. Glucocorticoids relieve inflammation and also assist in opening air passages. Mucolytics decrease the thickness of pulmonary secretions so that they can be expectorated more easily. |

| Provide suctioning, if needed. | Some patients may have a weakened cough that inhibits their ability to clear secretions from the mouth and throat. Patients with muscle disorders or those who have experienced a stroke (i.e., cerebral vascular accident) are at risk for aspiration, which could lead to pneumonia and hypoxia. Provide oral suction if the patient is unable to clear secretions from the mouth and pharynx. See the “Tracheostomy Care and Suctioning” chapter in Open RN Nursing Skills for additional details on suctioning. |

| Provide pain relief, If needed. | Provide adequate pain relief if the patient is reporting pain. Pain increases anxiety and metabolic demands, which, in turn, increase the need for more oxygen supply. |

| Consider side effects of pain medication. | A common side effect of pain medication is respiratory depression. For more information about managing respiratory depression, see the “Pain Management” section of the “Comfort” chapter. |

| Consider other devices to enhance clearance of secretions. | Chest physiotherapy and specialized devices assist with secretion clearance, such as handheld flutter valves or vests that inflate and vibrate the chest wall. Consult with a respiratory therapist as needed based on the patient’s situation. |

| Plan frequent rest periods between activities. | Plan interventions for patients with dyspnea so they can rest frequently and decrease oxygen demand. |

| Consider other potential causes of dyspnea. | If a patient’s level of dyspnea is worsening, assess for other underlying causes in addition to the primary diagnosis. For example, are there other respiratory, cardiovascular, or hematological conditions occurring? Start by reviewing the patient’s most recent hemoglobin and hematocrit lab results, as well as any other diagnostic tests such as chest X-rays and ABG results. Completing a thorough assessment may reveal abnormalities in these systems to report to the health care provider. |

| Consider obstructive sleep apnea. | Patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) are often not previously diagnosed prior to hospitalization. The nurse may notice the patient snores, has pauses in breathing while snoring, has decreased oxygen saturation levels while sleeping, or awakens feeling not rested. These signs may indicate the patient is unable to maintain an open airway while sleeping, resulting in periods of apnea and hypoxia. If these apneic periods are noticed but have not been previously documented, the nurse should report these findings to the health care provider for further testing and follow-up. A prescription for a CPAP or BiPAP device while sleeping may be needed to prevent adverse outcomes. |

| Monitor patient’s anxiety. | Assess patient’s anxiety. Anxiety often accompanies the feeling of dyspnea and can worsen it. Anxiety in patients with COPD is chronically undertreated. It is important for the nurse to address the feelings of anxiety in addition to the feelings of dyspnea. Anxiety can be relieved by teaching enhanced breathing and coughing techniques, encouraging relaxation techniques, or administering antianxiety medications. |

Enhanced Breathing and Coughing Techniques

In addition to oxygen therapy and the interventions listed in Table 8.2b, there are several techniques a nurse can teach a patient to use to enhance their breathing and coughing. These techniques include pursed-lip breathing, incentive spirometry, coughing and deep breathing, and the huffing technique. Additionally, vibratory positive expiratory pressure (PEP) therapy can be incorporated in collaboration with a respiratory therapist.

Pursed-lip Breathing

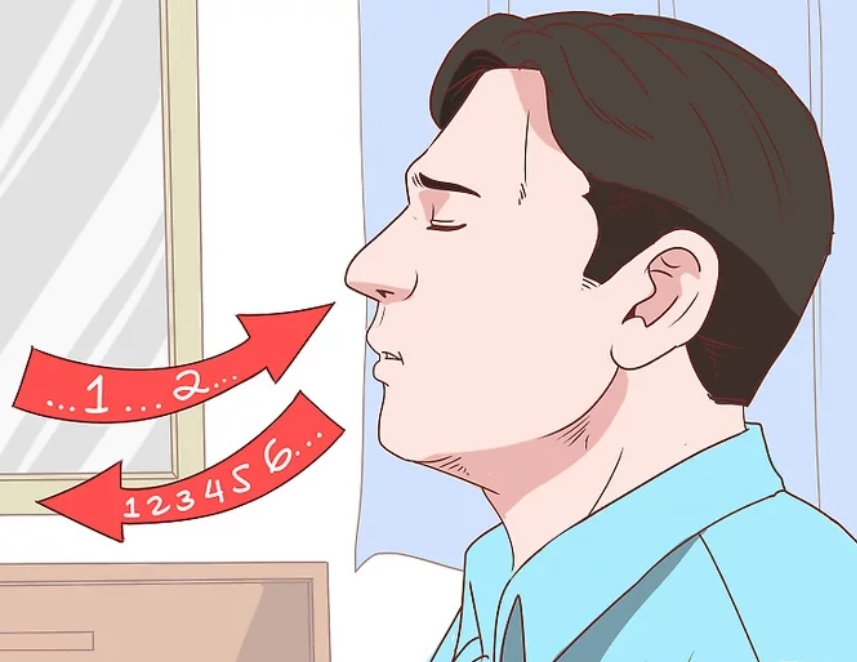

Pursed-lip breathing is a technique that decreases dyspnea by teaching people to control their oxygenation and ventilation. See Figure 8.5[13] for an illustration of pursed-lip breathing. The technique teaches a person to inhale through the nose and exhale through the mouth at a slow, controlled flow. This type of exhalation gives the person a puckered or pursed-lip appearance. By prolonging the expiratory phase of respiration, a small amount of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is created in the airways that helps to keep them open so that more air can be exhaled. This subsequently reduces air trapping that commonly occurs in conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Pursed-lip breathing relieves the feeling of shortness of breath, decreases the work of breathing, and improves gas exchange. People also regain a sense of control over their breathing while simultaneously increasing their relaxation.[14]

Incentive Spirometry

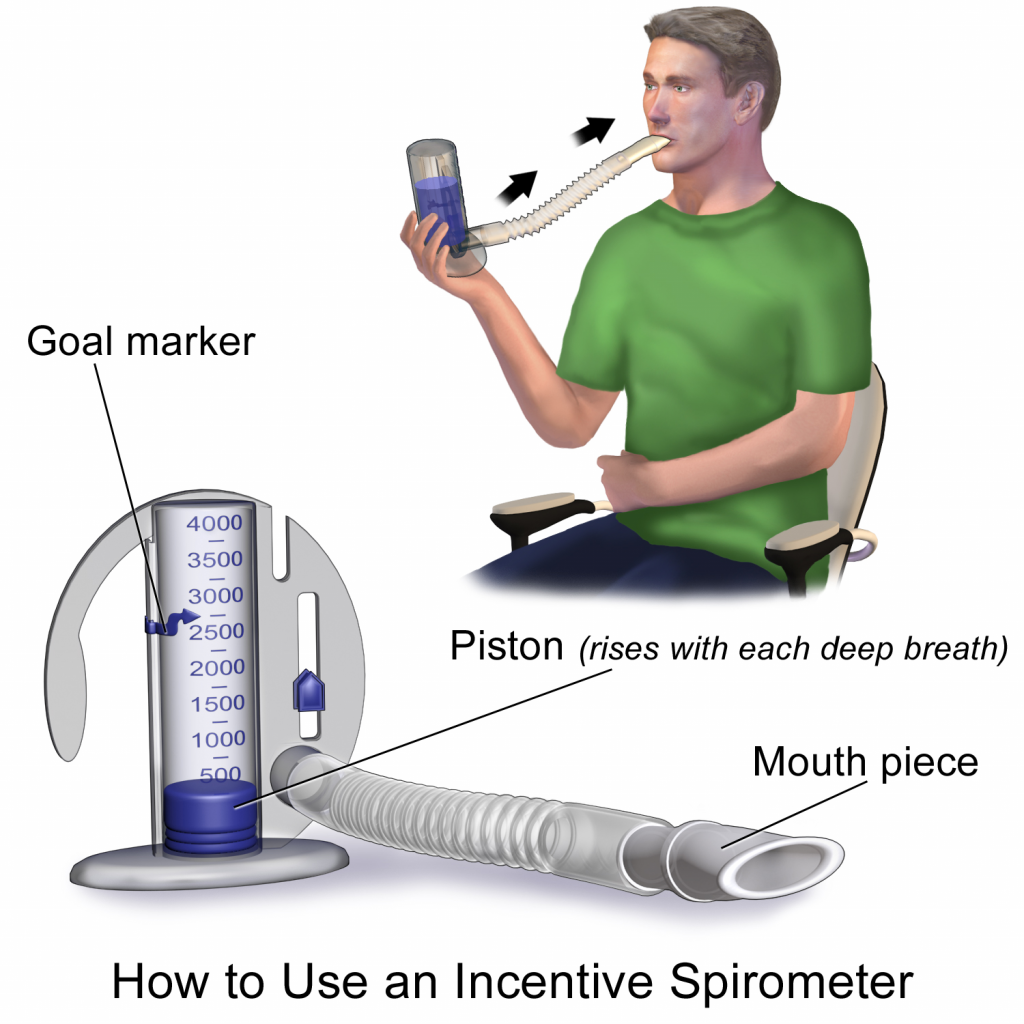

An incentive spirometer is a medical device commonly prescribed after surgery to expand the lungs, reduce the buildup of fluid in the lungs, and prevent pneumonia. See Figure 8.6[15] for an image of a patient using an incentive spirometer. While sitting upright, if possible, the patient should place the mouthpiece in their mouth and create a tight seal with their lips around it. They should breathe in slowly and as deeply as possible through the tubing with the goal of raising the piston to their prescribed level. The resistance indicator on the right side should be monitored to ensure they are not breathing in too quickly. The patient should attempt to hold their breath for as long as possible (at least 5 seconds) and then exhale and rest for a few seconds. Coughing is expected. Encourage the patient to expel the mucus and not swallow it. This technique should be repeated by the patient 10 times every hour while awake.[16] The nurse may delegate this intervention to unlicensed assistive personnel, but the frequency in which it is completed and the volume achieved should be documented and monitored by the nurse.

Coughing and Deep Breathing

Coughing and deep breathing is a breathing technique similar to incentive spirometry but no device is required. The patient is encouraged to take deep, slow breaths and then exhale slowly. After each set of breaths, the patient should cough. This technique is repeated 3 to 5 times every hour.

Huffing Technique

The huffing technique is helpful to teach patients who have difficulty coughing. Teach the patient to inhale with a medium-sized breath and then make a sound like “ha” to push the air out quickly with the mouth slightly open.

Vibratory PEP Therapy

Vibratory Positive Expiratory Pressure (PEP) Therapy uses handheld devices such as flutter valves or Acapella devices for patients who need assistance in clearing mucus from their airways. These devices require a prescription and are used in collaboration with a respiratory therapist or advanced health care provider. To use vibratory PEP therapy, the patient should sit up, take a deep breath, and blow into the device. A flutter valve within the device creates vibrations that help break up the mucus so the patient can cough and spit it out. Additionally, a small amount of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is created in the airways that helps to keep them open so that more air can be exhaled. See the supplementary video below regarding how to use the flutter valve device.

View this video on Using a Flutter Valve Device (Acapella).[17]

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “2322_Fig_23.33-a.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “2325_Carbon_Dioxide_Transport.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “OxyWatch_C20_Pulse_Oximeter.png” by Thinkpaul is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Patel, Miao, Yetiskul, and Majmundar and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Castro and Keenaghan and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Cynosis.JPG” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Patel, Miao, Yetiskul, and Majmundar and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- "v4-460px-Live-With-Chronic-Obstructive-Pulmonary-Disease-Step-8.jpg” by unknown is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. Access for free at https://www.wikihow.com/Live-With-Chronic-Obstructive-Pulmonary-Disease ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Nguyen and Duong and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Incentive Spirometer.png” by BruceBlaus is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2018, May 2). Incentive spirometer. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/4302-incentive-spirometer ↵

- NHS University Hospitals Plymouth Physiotherapy. (2015, May 12). Acapella. [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/XOvonQVCE6Y ↵

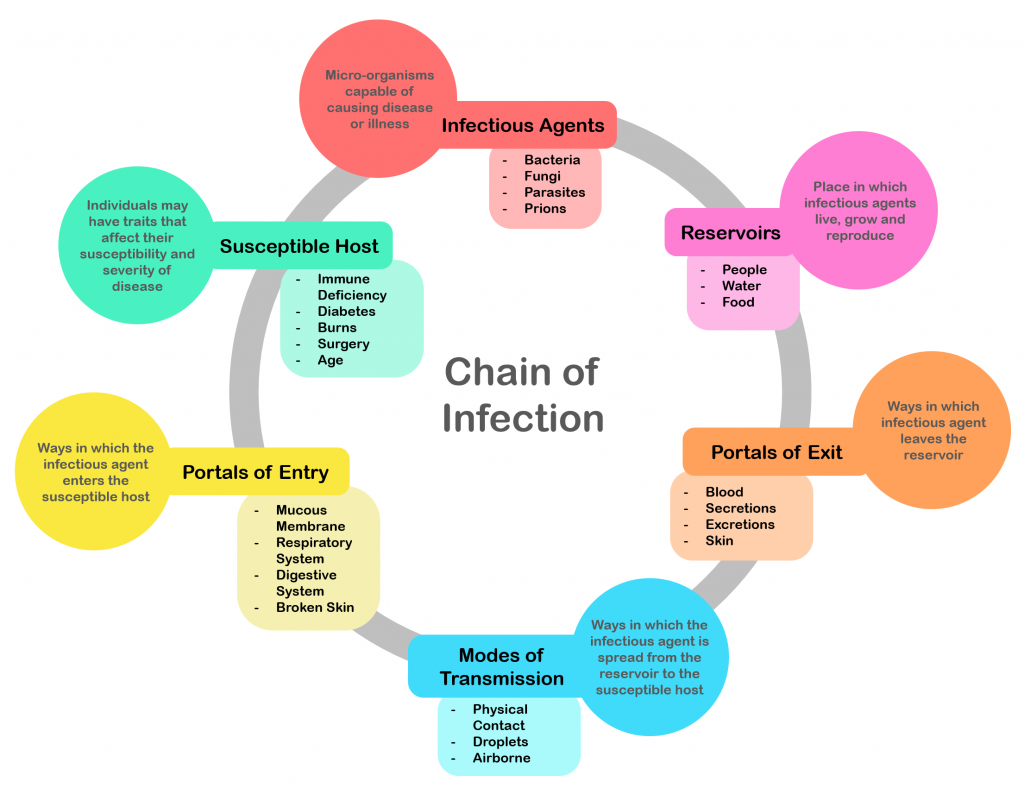

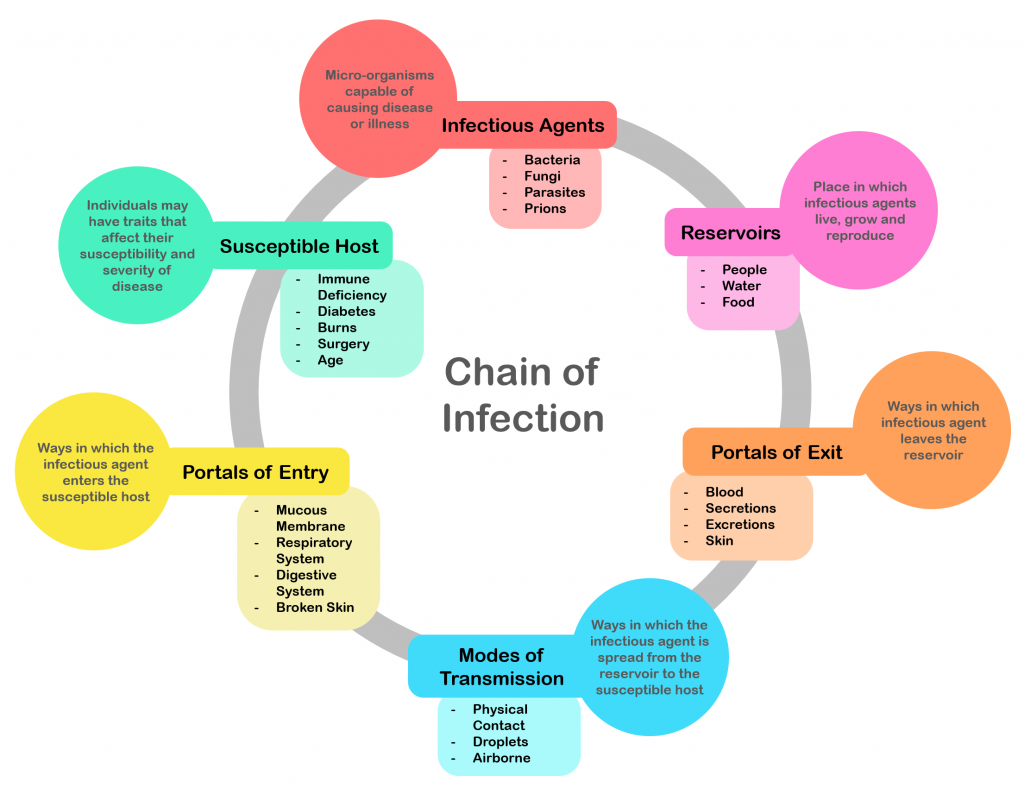

In addition to recognizing signs of infection and educating patients about the treatment of their infection, nurses also play an important role in preventing the spread of infection. A cyclic process known as the chain of infection describes the transmission of an infection. By implementing interventions to break one or more links in the chain of infection, the spread of infection can be stopped. See Figure 9.16[1] for an illustration of the links within the chain of infection. These links are described as the following:

- Infectious Agent: A causative organism, such as bacteria, virus, fungi, parasite.

- Reservoir: A place where the organism grows, such as in blood, food, or a wound.

- Portal of Exit: The method by which the organism leaves the reservoir, such as through respiratory secretions, blood, urine, breast milk, or feces.

- Mode of Transmission: The vehicle by which the organism is transferred such as physical contact, inhalation, or injection. The most common vehicles are respiratory secretions spread by a cough, sneeze, or on the hands. A single sneeze can send thousands of virus particles into the air.

- Portal of Entry: The method by which the organism enters a new host, such as through mucous membranes or nonintact skin.

- Susceptible Host: The susceptible individual the organism has invaded.[2]

For a pathogen to continue to exist, it must put itself in a position to be transmitted to a new host, leaving the infected host through a portal of exit. Similar to portals of entry, the most common portals of exit include the skin and the respiratory, urogenital, and gastrointestinal tracts. Coughing and sneezing can expel thousands of pathogens from the respiratory tract into the environment. Other pathogens are expelled through feces, urine, semen, and vaginal secretions. Pathogens that rely on insects for transmission exit the body in the blood extracted by a biting insect.[3]

The pathogen enters a new individual via a portal of entry, such as mucous membranes or nonintact skin. If the individual has a weakened immune system or their natural defenses cannot fend off the pathogen, they become infected.

Interventions to Break the Chain of Infection

Infections can be stopped from spreading by interrupting this chain at any link. Chain links can be broken by disinfecting the environment, sterilizing medical instruments and equipment, covering coughs and sneezes, using good hand hygiene, implementing standard and transmission-based precautions, appropriately using personal protective equipment, encouraging patients to stay up-to-date on vaccines (including the flu shot), following safe injection practices, and promoting the optimal functioning of the natural immune system with good nutrition, rest, exercise, and stress management.

Disinfection and Sterilization

Disinfection and sterilization are used to kill microorganisms and remove harmful pathogens from the environment and equipment to decrease the chance of spreading infection. Disinfection is the removal of microorganisms. However, disinfection does not destroy all spores and viruses. Sterilization is a process used on equipment and the environment to destroy all pathogens, including spores and viruses. Sterilization methods include steam, boiling water, dry heat, radiation, and chemicals. Because of the harshness of these sterilization methods, skin can only be disinfected and not sterilized.[4]

Standard and Transmission-Based Precautions

To protect patients and health care workers from the spread of pathogens, the CDC has developed precautions to use during patient care that address portals of exit, methods of transmission, and portals of entry. These precautions include standard precautions and transmission-based precautions.

Standard Precautions

Standard precautions are used when caring for all patients to prevent healthcare-associated infections. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), standard precautions are the minimum infection prevention practices that apply to all patient care, regardless of suspected or confirmed infection status of the patient, in any setting where health care is delivered. These precautions are based on the principle that all blood, body fluids (except sweat), nonintact skin, and mucous membranes may contain transmissible infectious agents. These standards reduce the risk of exposure for the health care worker and protect the patient from potential transmission of infectious organisms.[5] See Figure 9.17[6] for an image of some of the components of standard precautions.

Current standard precautions according to the CDC include the following:

- Appropriate hand hygiene

- Use of personal protective equipment (e.g., gloves, gowns, masks, eyewear) whenever infectious material exposure may occur

- Appropriate patient placement and care using transmission-based precautions when indicated

- Respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette

- Proper handling and cleaning of environment, equipment, and devices

- Safe handling of laundry

- Sharps safety (i.e., engineering and work practice controls)

- Aseptic technique for invasive nursing procedures such as parenteral medication administration[7]

![]“hand-disinfection-4954840_960_720.jpg” by KlausHausmann is licensed under CC0 Image showing hand sanitizer, gloves, and a surgical mask](https://nicoletcollege.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/55/2022/04/hand-sanitizer-1024x685.png)

Hand Hygiene

Hand hygiene, although simple, is still the best and most effective way to prevent the spread of infection. The 2021 National Patient Safety Goals from The Joint Commission encourages infection prevention strategy practices such as implementing the hand hygiene guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control.[8] Accepted methods for hand hygiene include using either soap and water or alcohol-based hand sanitizer. It is essential for all health care workers to use proper hand hygiene at the appropriate times, such as the following:

- Immediately before touching a patient

- Before performing an aseptic task or handling invasive devices

- Before moving from a soiled body site to a clean body site on a patient

- After touching a patient or their immediate environment

- After contact with blood, body fluids, or contaminated surfaces (with or without glove use)

- Immediately after glove removal[9]

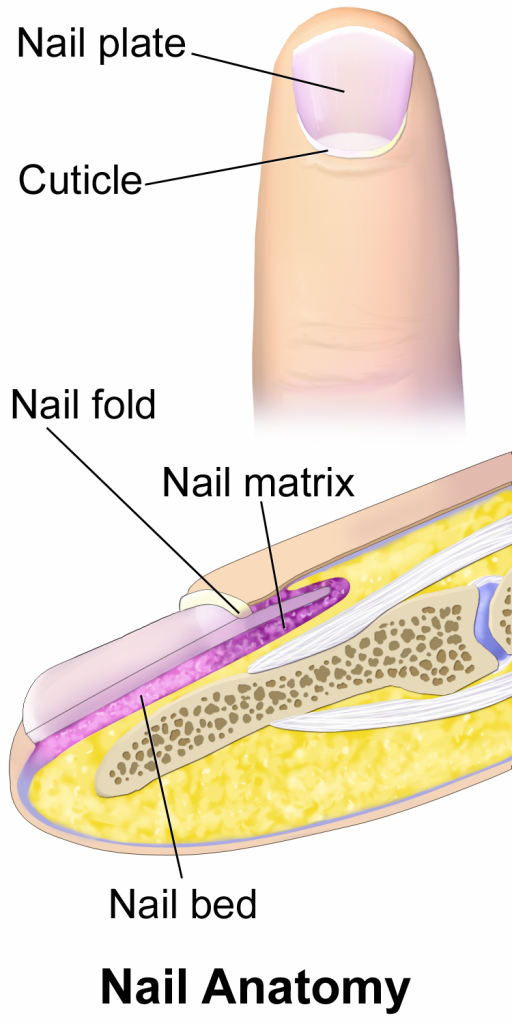

Hand hygiene also includes health care workers keeping their nails short with tips less than 0.5 inches and no nail polish. Nails should be natural, and artificial nails or tips should not be worn. Artificial nails and chipped nail polish have been associated with a higher level of pathogens carried on the hands of the nurse despite hand hygiene.[10]

Respiratory Hygiene/Cough Etiquette

Respiratory hygiene is targeted at patients, accompanying family members and friends, and staff members with undiagnosed transmissible respiratory infections. It applies to any person with signs of illness, including cough, congestion, or increased production of respiratory secretions when entering a health care facility. The elements of respiratory hygiene include the following:

- Education of health care facility staff, patients, and visitors

- Posted signs, in language(s) appropriate to the population served, with instructions to patients and accompanying family members or friends

- Source control measures for a coughing person (e.g., covering the mouth/nose with a tissue when coughing and prompt disposal of used tissues, or applying surgical masks on the coughing person to contain secretions)

- Hand hygiene after contact with one’s respiratory secretions

- Spatial separation, ideally greater than 3 feet, of persons with respiratory infections in common waiting areas when possible[11]

Health care personnel are advised to wear a mask and use frequent hand hygiene when examining and caring for patients with signs and symptoms of a respiratory infection. Health care personnel who have a respiratory infection are advised to stay home or avoid direct patient contact, especially with high-risk patients. If this is not possible, then a mask should be worn while providing patient care.[12]

Personal Protective Equipment

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) includes gloves, gowns, face shields, goggles, and masks used to prevent the spread of infection to and from patients and health care providers. See Figure 9.18[13] for an image of a nurse wearing PPE. Depending upon the anticipated exposure and type of pathogen, PPE may include the use of gloves, a fluid-resistant gown, goggles or a face shield, and a mask or respirator. When used while caring for a patient with transmission-based precautions, PPE supplies are typically stored in an isolation cart next to the patient’s room.

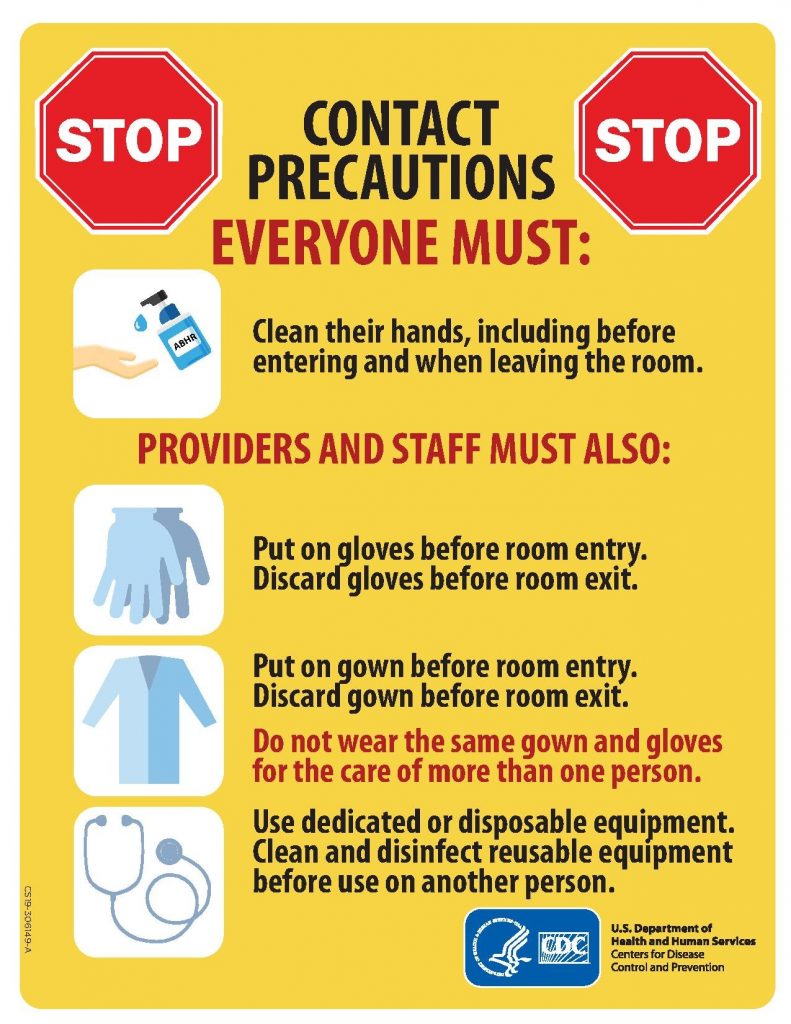

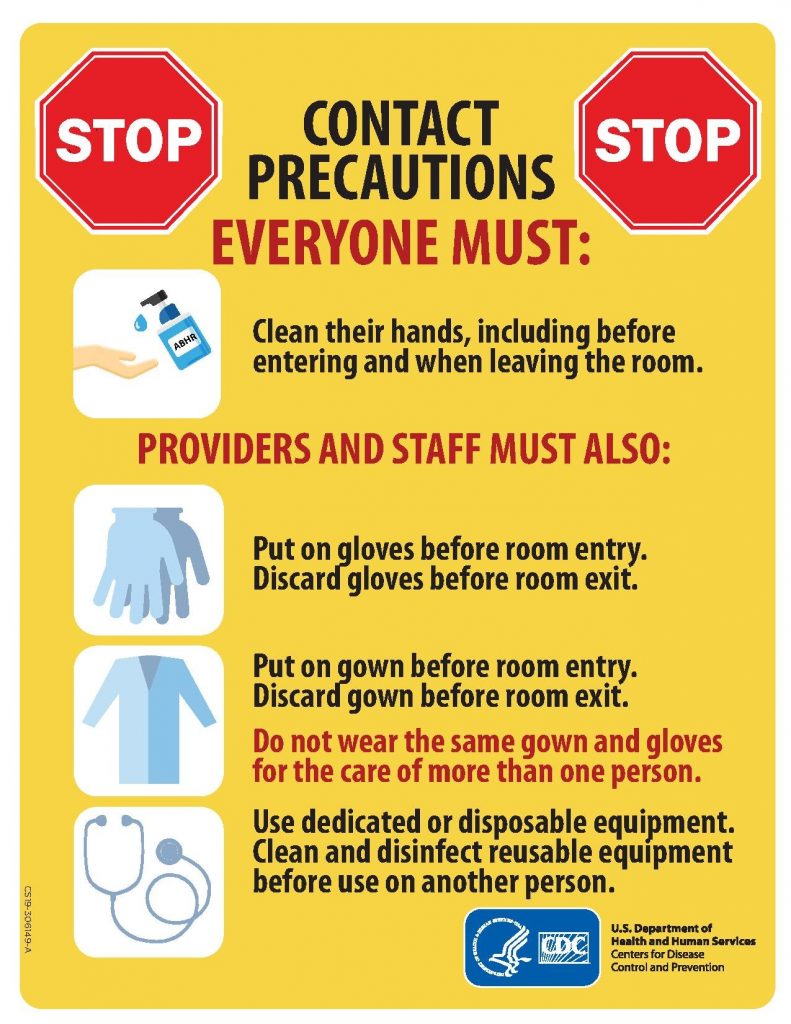

Transmission-Based Precautions

In addition to standard precautions, transmission-based precautions are used for patients with documented or suspected infection of highly-transmissible pathogens, such as C. difficile (C-diff), Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), measles, and tuberculosis (TB). For patients with these types of pathogens, standard precautions are used along with specific transmission-based precautions.[14]

There are three categories of transmission-based precautions: contact precautions, droplet precautions, and airborne precautions. Transmission-based precautions are used when the route(s) of transmission of a specific disease are not completely interrupted using standard precautions alone.

Some diseases, such as tuberculosis, have multiple routes of transmission so more than one transmission-based precaution category must be implemented. See Table 9.6 outlining the categories of transmission precautions with associated PPE and other precautions. When possible, patients with transmission-based precautions should be placed in a single occupancy room with dedicated patient care equipment (e.g., blood pressure cuffs, stethoscope, and thermometer stay in the patient’s room). A card is posted outside the door alerting staff and visitors to required precautions before entering the room. See Figure 9.19[15] for an example of signage used for a patient with contact precautions. Transport of the patient and unnecessary movement outside the patient room should be limited. When transmission-based precautions are implemented, it is also important for the nurse to make efforts to counteract possible adverse effects of these precautions on patients, such as anxiety, depression, perceptions of stigma, and reduced contact with clinical staff.[16]

Table 9.6 Transmission-Based Precautions[17]

| Precaution | Implementation | PPE and Other Precautions |

|---|---|---|

| Contact | Known or suspected infections with increased risk for contact transmission (e.g., draining wounds, fecal incontinence) or with epidemiologically important organisms, such as C-diff, MRSA, VRE, or RSV | Gloves

Gown Dedicated equipment Limit patient transport out of room Prioritized disinfection of the room Note: Use only soap and water for hand hygiene in patients with C. difficile infection. |

| Droplet | Known or suspected infection with pathogens transmitted by large respiratory droplets generated by coughing, sneezing, or talking, such as influenza or pertussis | Mask

Goggles or face shield |

| Airborne | Known or suspected infection with pathogens transmitted by small respiratory droplets, such as measles and coronavirus | Fit-tested N-95 respirator

Airborne infection isolation room Single-patient room Patient door closed Restricted susceptible personnel room entry |

Patient Transport

Several principles are used to guide transport of patients requiring transmission-based precautions. In the inpatient and residential settings, these principles include the following:

- Limit transport for essential purposes only, such as diagnostic and therapeutic procedures that cannot be performed in the patient’s room

- When transporting, use appropriate barriers on the patient consistent with the route and risk of transmission (e.g., mask, gown, covering the affected areas when infectious skin lesions or drainage is present)

- Notify health care personnel in the receiving area of the impending arrival of the patient and of the precautions necessary to prevent transmission[18]

Enteric Precautions

Enteric precautions are used when there is the presence, or suspected presence, of gastrointestinal pathogens such as Clostridium difficile (C-diff) or norovirus. These pathogens are present in feces, so health care workers should always wear a gown in the patient room to prevent inadvertent fecal contamination of their clothing from contact with contaminated surfaces.

In addition to contact precautions, enteric precautions include the following:

- Using only soap and water for hand hygiene. Do not use hand sanitizer because it is not effective against C-diff.

- Using a special disinfecting process. Special disinfecting should be used after patient discharge and includes disinfection of the mattress.

Reverse Isolation

Reverse isolation, also called neutropenic precautions, is used for patients who have compromised immune systems and low neutrophil levels. This type of isolation protects the patient from pathogens in their environment. In addition to using contact precautions to protect the patient, reverse isolation precautions include the following:

- Meticulous hand hygiene by all visitors, staff, and the patient

- Frequently monitoring for signs and symptoms of infection and sepsis

- Not allowing live plants, fresh flowers, fresh raw fruits or vegetables, sushi, deli foods, or cheese into the room due to bacteria and fungi

- Placement in a private room or a positive pressure room

- Limited transport and movement of the patient outside of the room

- Masking of the patient for transport with a surgical mask[19]

Psychological Effects of Isolation

Although the use of transmission-based precautions is needed to prevent the spread of infection, it is important for nurses to be aware of the potential psychological impact on the patient. Research has shown that isolation can cause negative impact on patient mental well-being and behavior, including higher scores for depression, anxiety, and anger among isolated patients. It has also been found that health care workers spend less time with patients in isolation, resulting in a negative impact on patient safety.[20]

Patient and family education at the time of instituting transmission-based precautions is a critical component of the process to reduce anxiety and distress. Patients often feel stigmatized when placed in isolation, so it is important for them to understand the rationale of the precautions to keep themselves and others free from the spread of disease. Preparing patients emotionally will also help decrease their anxiety and help them cope with isolation.[21] It is also important to provide distractions from boredom, such as music, television, video games, magazines, or books, as appropriate.

Aseptic and Sterile Techniques

In addition to using standard precautions and transmission-based precautions, aseptic technique (also called medical asepsis) is used to prevent the transfer of microorganisms from one person or object to another during a medical procedure. For example, a nurse administering parenteral medication or performing urinary catheterization uses aseptic technique. When performed properly, aseptic technique prevents contamination and transfer of pathogens to the patient from caregiver hands, surfaces, and equipment during routine care or procedures. It is important to remember that potentially infectious microorganisms can be present in the environment, on instruments, in liquids, on skin surfaces, or within a wound.[22]

There is often misunderstanding between the terms aseptic technique and sterile technique in the health care setting. Both asepsis and sterility are closely related with the shared concept being the removal of harmful microorganisms that can cause infection. In the most simplistic terms, aseptic technique involves creating a protective barrier to prevent the spread of pathogens, whereas sterile technique is a purposeful attack on microorganisms. Sterile technique (also called surgical asepsis) seeks to eliminate every potential microorganism in and around a sterile field while also maintaining objects as free from microorganisms as possible. Sterile fields are implemented during surgery, as well as during nursing procedures such as the insertion of a urinary catheter, changing dressings on open wounds, and performing central line care. See Figure 9.20[23] for an image of a sterile field during surgery. Sterile technique requires a combination of meticulous hand washing, creating and maintaining a sterile field, using long-lasting antimicrobial cleansing agents such as Betadine, donning sterile gloves, and using sterile devices and instruments.[24]

Read additional information about aseptic and sterile technique in the "Aseptic Technique" in Open RN Nursing Skills.

Read a continuing education article about Sterile Technique and surgical scrubbing.

Other Hygienic Patient Care Interventions

In addition to implementing standard and transmission-based precautions and utilizing aseptic and sterile technique when performing procedures, nurses implement many interventions to place a patient in the best health possible to prevent an infection or treat infection. These interventions include actions like encouraging rest and good nutrition, teaching stress management, providing good oral care, encouraging daily bathing, and changing linens. It is also important to consider how gripper socks, mobile devices, and improper glove usage can contribute to the transmission of pathogens.

Oral Care

Patient hygiene is important in the prevention and spread of infection. Although oral care may be given a low priority, research has found that poor oral care is associated with the spread of infection, poor health outcomes, and poor nutrition. Oral care should be performed in the morning, after meals, and before bed.[25]

Daily Bathing

Daily bathing is another intervention that may be viewed as time-consuming and receive low priority, but it can have a powerful impact on decreasing the spread of infection. Studies have shown a significant decrease in healthcare-associated infections with daily bathing using chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) wipes or solution. The use of traditional soap and water baths do not reduce infection rates as significantly as CHG products, and wash basins have also been shown to be a reservoir for pathogens.[26]

Linens

Changing bed linens, towels, and a gown regularly eliminates potential reservoirs of bacteria. Fresh linens also promote patient comfort.

Gripper Socks

Have you ever thought about what happens to the bed linens when a patient returns from a walk in the hallway with gripper socks and gets back into bed with these socks? Research demonstrates that pathogens from the floor are transferred to the patient bed linens from the gripper socks. Nurses should remove gripper socks that were used for walking before patients climb into bed. They should also throw the socks away when the patient is discharged instead of sending them home.[27]

Cellular Phones and Mobile Devices

Research has shown that cell phones and mobile devices carry many pathogens and are dirtier than a toilet seat or the bottom of a shoe. Patients, staff, and visitors routinely bring these mobile devices into health care facilities, which can cause the spread of disease. Nurses should frequently wipe mobile devices with disinfectant. They should encourage patients and visitors to disinfect phones frequently and avoid touching the face after having touched a mobile device.[28]

Gloves

Although gloves are used to prevent the spread of infection, they can also contribute to the spread of infection if used improperly. For example, research has shown that hand hygiene opportunities are being missed because of the overuse of gloves. For example, a nurse may don gloves to suction a patient but neglect to remove them and perform hand hygiene before performing the next procedure on the same patient. This can potentially cause the spread of secondary infection. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that gloves should be worn when there is an expected risk of exposure to blood or body fluids or to protect the hands from chemicals and hazardous drugs, but hand hygiene is the best method of disease prevention and is preferred over wearing gloves when the exposure risk is minimal. Nurses have the perception that wearing gloves provides extra protection and cleanliness. However, the opposite is true. Nonsterile gloves have a high incidence of contamination with a range of bacteria, which means that a gloved hand is dirtier than a washed hand. Research has shown that nearly 40% of the times that gloves are used in patient care, there is cross contamination. The most striking example of cross contamination includes situations when gloves are used for toileting a patient and not being removed before touching other surfaces or the patient.[29],[30],[31]

Glove-related contact dermatitis has also become an important issue in recent years as more and more nurses are experiencing damage to the hands. Contact dermatitis can develop from repeated use of gloves and develops as dry, itchy, irritated areas on the skin of the hands. See Figure 9.21[32] for an image of contact dermatitis from gloves. Because the skin is the first line of defense in preventing pathogens from entering the body, maintaining intact skin is very important to prevent nurses from exposure to pathogens.

In addition to recognizing signs of infection and educating patients about the treatment of their infection, nurses also play an important role in preventing the spread of infection. A cyclic process known as the chain of infection describes the transmission of an infection. By implementing interventions to break one or more links in the chain of infection, the spread of infection can be stopped. See Figure 9.16[33] for an illustration of the links within the chain of infection. These links are described as the following:

- Infectious Agent: A causative organism, such as bacteria, virus, fungi, parasite.

- Reservoir: A place where the organism grows, such as in blood, food, or a wound.

- Portal of Exit: The method by which the organism leaves the reservoir, such as through respiratory secretions, blood, urine, breast milk, or feces.

- Mode of Transmission: The vehicle by which the organism is transferred such as physical contact, inhalation, or injection. The most common vehicles are respiratory secretions spread by a cough, sneeze, or on the hands. A single sneeze can send thousands of virus particles into the air.

- Portal of Entry: The method by which the organism enters a new host, such as through mucous membranes or nonintact skin.

- Susceptible Host: The susceptible individual the organism has invaded.[34]

For a pathogen to continue to exist, it must put itself in a position to be transmitted to a new host, leaving the infected host through a portal of exit. Similar to portals of entry, the most common portals of exit include the skin and the respiratory, urogenital, and gastrointestinal tracts. Coughing and sneezing can expel thousands of pathogens from the respiratory tract into the environment. Other pathogens are expelled through feces, urine, semen, and vaginal secretions. Pathogens that rely on insects for transmission exit the body in the blood extracted by a biting insect.[35]

The pathogen enters a new individual via a portal of entry, such as mucous membranes or nonintact skin. If the individual has a weakened immune system or their natural defenses cannot fend off the pathogen, they become infected.

Interventions to Break the Chain of Infection

Infections can be stopped from spreading by interrupting this chain at any link. Chain links can be broken by disinfecting the environment, sterilizing medical instruments and equipment, covering coughs and sneezes, using good hand hygiene, implementing standard and transmission-based precautions, appropriately using personal protective equipment, encouraging patients to stay up-to-date on vaccines (including the flu shot), following safe injection practices, and promoting the optimal functioning of the natural immune system with good nutrition, rest, exercise, and stress management.

Disinfection and Sterilization

Disinfection and sterilization are used to kill microorganisms and remove harmful pathogens from the environment and equipment to decrease the chance of spreading infection. Disinfection is the removal of microorganisms. However, disinfection does not destroy all spores and viruses. Sterilization is a process used on equipment and the environment to destroy all pathogens, including spores and viruses. Sterilization methods include steam, boiling water, dry heat, radiation, and chemicals. Because of the harshness of these sterilization methods, skin can only be disinfected and not sterilized.[36]

Standard and Transmission-Based Precautions

To protect patients and health care workers from the spread of pathogens, the CDC has developed precautions to use during patient care that address portals of exit, methods of transmission, and portals of entry. These precautions include standard precautions and transmission-based precautions.

Standard Precautions

Standard precautions are used when caring for all patients to prevent healthcare-associated infections. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), standard precautions are the minimum infection prevention practices that apply to all patient care, regardless of suspected or confirmed infection status of the patient, in any setting where health care is delivered. These precautions are based on the principle that all blood, body fluids (except sweat), nonintact skin, and mucous membranes may contain transmissible infectious agents. These standards reduce the risk of exposure for the health care worker and protect the patient from potential transmission of infectious organisms.[37] See Figure 9.17[38] for an image of some of the components of standard precautions.

Current standard precautions according to the CDC include the following:

- Appropriate hand hygiene

- Use of personal protective equipment (e.g., gloves, gowns, masks, eyewear) whenever infectious material exposure may occur

- Appropriate patient placement and care using transmission-based precautions when indicated

- Respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette

- Proper handling and cleaning of environment, equipment, and devices

- Safe handling of laundry

- Sharps safety (i.e., engineering and work practice controls)

- Aseptic technique for invasive nursing procedures such as parenteral medication administration[39]

![]“hand-disinfection-4954840_960_720.jpg” by KlausHausmann is licensed under CC0 Image showing hand sanitizer, gloves, and a surgical mask](https://nicoletcollege.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/55/2022/04/hand-sanitizer-1024x685.png)

Hand Hygiene

Hand hygiene, although simple, is still the best and most effective way to prevent the spread of infection. The 2021 National Patient Safety Goals from The Joint Commission encourages infection prevention strategy practices such as implementing the hand hygiene guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control.[40] Accepted methods for hand hygiene include using either soap and water or alcohol-based hand sanitizer. It is essential for all health care workers to use proper hand hygiene at the appropriate times, such as the following:

- Immediately before touching a patient

- Before performing an aseptic task or handling invasive devices

- Before moving from a soiled body site to a clean body site on a patient

- After touching a patient or their immediate environment

- After contact with blood, body fluids, or contaminated surfaces (with or without glove use)

- Immediately after glove removal[41]

Hand hygiene also includes health care workers keeping their nails short with tips less than 0.5 inches and no nail polish. Nails should be natural, and artificial nails or tips should not be worn. Artificial nails and chipped nail polish have been associated with a higher level of pathogens carried on the hands of the nurse despite hand hygiene.[42]

Respiratory Hygiene/Cough Etiquette

Respiratory hygiene is targeted at patients, accompanying family members and friends, and staff members with undiagnosed transmissible respiratory infections. It applies to any person with signs of illness, including cough, congestion, or increased production of respiratory secretions when entering a health care facility. The elements of respiratory hygiene include the following:

- Education of health care facility staff, patients, and visitors

- Posted signs, in language(s) appropriate to the population served, with instructions to patients and accompanying family members or friends

- Source control measures for a coughing person (e.g., covering the mouth/nose with a tissue when coughing and prompt disposal of used tissues, or applying surgical masks on the coughing person to contain secretions)

- Hand hygiene after contact with one’s respiratory secretions

- Spatial separation, ideally greater than 3 feet, of persons with respiratory infections in common waiting areas when possible[43]

Health care personnel are advised to wear a mask and use frequent hand hygiene when examining and caring for patients with signs and symptoms of a respiratory infection. Health care personnel who have a respiratory infection are advised to stay home or avoid direct patient contact, especially with high-risk patients. If this is not possible, then a mask should be worn while providing patient care.[44]

Personal Protective Equipment

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) includes gloves, gowns, face shields, goggles, and masks used to prevent the spread of infection to and from patients and health care providers. See Figure 9.18[45] for an image of a nurse wearing PPE. Depending upon the anticipated exposure and type of pathogen, PPE may include the use of gloves, a fluid-resistant gown, goggles or a face shield, and a mask or respirator. When used while caring for a patient with transmission-based precautions, PPE supplies are typically stored in an isolation cart next to the patient’s room.

Transmission-Based Precautions

In addition to standard precautions, transmission-based precautions are used for patients with documented or suspected infection of highly-transmissible pathogens, such as C. difficile (C-diff), Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), measles, and tuberculosis (TB). For patients with these types of pathogens, standard precautions are used along with specific transmission-based precautions.[46]

There are three categories of transmission-based precautions: contact precautions, droplet precautions, and airborne precautions. Transmission-based precautions are used when the route(s) of transmission of a specific disease are not completely interrupted using standard precautions alone.

Some diseases, such as tuberculosis, have multiple routes of transmission so more than one transmission-based precaution category must be implemented. See Table 9.6 outlining the categories of transmission precautions with associated PPE and other precautions. When possible, patients with transmission-based precautions should be placed in a single occupancy room with dedicated patient care equipment (e.g., blood pressure cuffs, stethoscope, and thermometer stay in the patient’s room). A card is posted outside the door alerting staff and visitors to required precautions before entering the room. See Figure 9.19[47] for an example of signage used for a patient with contact precautions. Transport of the patient and unnecessary movement outside the patient room should be limited. When transmission-based precautions are implemented, it is also important for the nurse to make efforts to counteract possible adverse effects of these precautions on patients, such as anxiety, depression, perceptions of stigma, and reduced contact with clinical staff.[48]

Table 9.6 Transmission-Based Precautions[49]

| Precaution | Implementation | PPE and Other Precautions |

|---|---|---|

| Contact | Known or suspected infections with increased risk for contact transmission (e.g., draining wounds, fecal incontinence) or with epidemiologically important organisms, such as C-diff, MRSA, VRE, or RSV | Gloves

Gown Dedicated equipment Limit patient transport out of room Prioritized disinfection of the room Note: Use only soap and water for hand hygiene in patients with C. difficile infection. |

| Droplet | Known or suspected infection with pathogens transmitted by large respiratory droplets generated by coughing, sneezing, or talking, such as influenza or pertussis | Mask

Goggles or face shield |

| Airborne | Known or suspected infection with pathogens transmitted by small respiratory droplets, such as measles and coronavirus | Fit-tested N-95 respirator

Airborne infection isolation room Single-patient room Patient door closed Restricted susceptible personnel room entry |

Patient Transport

Several principles are used to guide transport of patients requiring transmission-based precautions. In the inpatient and residential settings, these principles include the following:

- Limit transport for essential purposes only, such as diagnostic and therapeutic procedures that cannot be performed in the patient’s room

- When transporting, use appropriate barriers on the patient consistent with the route and risk of transmission (e.g., mask, gown, covering the affected areas when infectious skin lesions or drainage is present)

- Notify health care personnel in the receiving area of the impending arrival of the patient and of the precautions necessary to prevent transmission[50]

Enteric Precautions

Enteric precautions are used when there is the presence, or suspected presence, of gastrointestinal pathogens such as Clostridium difficile (C-diff) or norovirus. These pathogens are present in feces, so health care workers should always wear a gown in the patient room to prevent inadvertent fecal contamination of their clothing from contact with contaminated surfaces.

In addition to contact precautions, enteric precautions include the following:

- Using only soap and water for hand hygiene. Do not use hand sanitizer because it is not effective against C-diff.

- Using a special disinfecting process. Special disinfecting should be used after patient discharge and includes disinfection of the mattress.

Reverse Isolation

Reverse isolation, also called neutropenic precautions, is used for patients who have compromised immune systems and low neutrophil levels. This type of isolation protects the patient from pathogens in their environment. In addition to using contact precautions to protect the patient, reverse isolation precautions include the following:

- Meticulous hand hygiene by all visitors, staff, and the patient

- Frequently monitoring for signs and symptoms of infection and sepsis

- Not allowing live plants, fresh flowers, fresh raw fruits or vegetables, sushi, deli foods, or cheese into the room due to bacteria and fungi

- Placement in a private room or a positive pressure room

- Limited transport and movement of the patient outside of the room

- Masking of the patient for transport with a surgical mask[51]

Psychological Effects of Isolation

Although the use of transmission-based precautions is needed to prevent the spread of infection, it is important for nurses to be aware of the potential psychological impact on the patient. Research has shown that isolation can cause negative impact on patient mental well-being and behavior, including higher scores for depression, anxiety, and anger among isolated patients. It has also been found that health care workers spend less time with patients in isolation, resulting in a negative impact on patient safety.[52]

Patient and family education at the time of instituting transmission-based precautions is a critical component of the process to reduce anxiety and distress. Patients often feel stigmatized when placed in isolation, so it is important for them to understand the rationale of the precautions to keep themselves and others free from the spread of disease. Preparing patients emotionally will also help decrease their anxiety and help them cope with isolation.[53] It is also important to provide distractions from boredom, such as music, television, video games, magazines, or books, as appropriate.

Aseptic and Sterile Techniques

In addition to using standard precautions and transmission-based precautions, aseptic technique (also called medical asepsis) is used to prevent the transfer of microorganisms from one person or object to another during a medical procedure. For example, a nurse administering parenteral medication or performing urinary catheterization uses aseptic technique. When performed properly, aseptic technique prevents contamination and transfer of pathogens to the patient from caregiver hands, surfaces, and equipment during routine care or procedures. It is important to remember that potentially infectious microorganisms can be present in the environment, on instruments, in liquids, on skin surfaces, or within a wound.[54]

There is often misunderstanding between the terms aseptic technique and sterile technique in the health care setting. Both asepsis and sterility are closely related with the shared concept being the removal of harmful microorganisms that can cause infection. In the most simplistic terms, aseptic technique involves creating a protective barrier to prevent the spread of pathogens, whereas sterile technique is a purposeful attack on microorganisms. Sterile technique (also called surgical asepsis) seeks to eliminate every potential microorganism in and around a sterile field while also maintaining objects as free from microorganisms as possible. Sterile fields are implemented during surgery, as well as during nursing procedures such as the insertion of a urinary catheter, changing dressings on open wounds, and performing central line care. See Figure 9.20[55] for an image of a sterile field during surgery. Sterile technique requires a combination of meticulous hand washing, creating and maintaining a sterile field, using long-lasting antimicrobial cleansing agents such as Betadine, donning sterile gloves, and using sterile devices and instruments.[56]

Read additional information about aseptic and sterile technique in the "Aseptic Technique" in Open RN Nursing Skills.

Read a continuing education article about Sterile Technique and surgical scrubbing.

Other Hygienic Patient Care Interventions

In addition to implementing standard and transmission-based precautions and utilizing aseptic and sterile technique when performing procedures, nurses implement many interventions to place a patient in the best health possible to prevent an infection or treat infection. These interventions include actions like encouraging rest and good nutrition, teaching stress management, providing good oral care, encouraging daily bathing, and changing linens. It is also important to consider how gripper socks, mobile devices, and improper glove usage can contribute to the transmission of pathogens.

Oral Care

Patient hygiene is important in the prevention and spread of infection. Although oral care may be given a low priority, research has found that poor oral care is associated with the spread of infection, poor health outcomes, and poor nutrition. Oral care should be performed in the morning, after meals, and before bed.[57]

Daily Bathing

Daily bathing is another intervention that may be viewed as time-consuming and receive low priority, but it can have a powerful impact on decreasing the spread of infection. Studies have shown a significant decrease in healthcare-associated infections with daily bathing using chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) wipes or solution. The use of traditional soap and water baths do not reduce infection rates as significantly as CHG products, and wash basins have also been shown to be a reservoir for pathogens.[58]

Linens

Changing bed linens, towels, and a gown regularly eliminates potential reservoirs of bacteria. Fresh linens also promote patient comfort.

Gripper Socks

Have you ever thought about what happens to the bed linens when a patient returns from a walk in the hallway with gripper socks and gets back into bed with these socks? Research demonstrates that pathogens from the floor are transferred to the patient bed linens from the gripper socks. Nurses should remove gripper socks that were used for walking before patients climb into bed. They should also throw the socks away when the patient is discharged instead of sending them home.[59]

Cellular Phones and Mobile Devices

Research has shown that cell phones and mobile devices carry many pathogens and are dirtier than a toilet seat or the bottom of a shoe. Patients, staff, and visitors routinely bring these mobile devices into health care facilities, which can cause the spread of disease. Nurses should frequently wipe mobile devices with disinfectant. They should encourage patients and visitors to disinfect phones frequently and avoid touching the face after having touched a mobile device.[60]

Gloves

Although gloves are used to prevent the spread of infection, they can also contribute to the spread of infection if used improperly. For example, research has shown that hand hygiene opportunities are being missed because of the overuse of gloves. For example, a nurse may don gloves to suction a patient but neglect to remove them and perform hand hygiene before performing the next procedure on the same patient. This can potentially cause the spread of secondary infection. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that gloves should be worn when there is an expected risk of exposure to blood or body fluids or to protect the hands from chemicals and hazardous drugs, but hand hygiene is the best method of disease prevention and is preferred over wearing gloves when the exposure risk is minimal. Nurses have the perception that wearing gloves provides extra protection and cleanliness. However, the opposite is true. Nonsterile gloves have a high incidence of contamination with a range of bacteria, which means that a gloved hand is dirtier than a washed hand. Research has shown that nearly 40% of the times that gloves are used in patient care, there is cross contamination. The most striking example of cross contamination includes situations when gloves are used for toileting a patient and not being removed before touching other surfaces or the patient.[61],[62],[63]

Glove-related contact dermatitis has also become an important issue in recent years as more and more nurses are experiencing damage to the hands. Contact dermatitis can develop from repeated use of gloves and develops as dry, itchy, irritated areas on the skin of the hands. See Figure 9.21[64] for an image of contact dermatitis from gloves. Because the skin is the first line of defense in preventing pathogens from entering the body, maintaining intact skin is very important to prevent nurses from exposure to pathogens.

Now that we have discussed the pathophysiology of our immune system and interventions to treat and prevent infection, let’s apply this information to using the nursing process when providing patient care.

Assessment

When assessing an individual who is feeling ill but has not yet been diagnosed with an infection, general symptoms associated with the prodromal period of disease may be present due to the activation of the immune system. These symptoms include a feeling of malaise (not feeling well), headache, fever, and lack of appetite. As an infection moves into the acute phase of disease, more specific symptoms and signs related to the specific type of infection will occur.

A fever is a common sign of inflammation and infection. A temperature of 38 degrees Celsius (100.4 degrees F) is generally considered a low-grade fever, and a temperature of 38.3 degrees Celsius (101 degrees F) is considered a fever.[65] As discussed earlier in this chapter, fever is part of the nonspecific innate immune response and can be beneficial in destroying pathogens. However, extremely elevated temperatures can cause cell and organ damage, and prolonged fever can cause dehydration.

Infection raises the metabolic rate, causing an increased heart rate. The respiratory rate may also increase as the body rids itself of carbon dioxide created during increased metabolism. However, be aware that an elevated heart rate above 90 and a respiratory rate above 20 are also criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) in patients with an existing infection.

As an infection develops, the lymph nodes that drain that area often become enlarged and tender. The swelling indicates that the lymphocytes and macrophages in the lymph node are fighting the infection. If a skin infection is developing, general signs of inflammation, such as redness, warmth, swelling, and tenderness, will occur at the site. As white blood cells migrate to the site, purulent drainage may occur.

Some viruses, bacteria, and toxins cause gastrointestinal inflammation, resulting in loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

See Table 9.7a for a comparison of expected findings on physical assessment versus unexpected findings indicating a new infectious process that requires notification of the health care provider.

Table 9.7a Expected Versus Unexpected Findings on Assessment Related to Infection

| Assessment | Expected Findings | Unexpected Findings to Report to Health Care Provider |

|---|---|---|

| Vital Signs | Within normal range | New temperature over 100.4 F or 38 C. |

| Neurological | Within baseline level of consciousness | New confusion and/or worsening level of consciousness. |

| Wound or Incision | Progressive healing of a wound with no signs of infection | New redness, warmth, tenderness, or purulent drainage from a wound. |

| Respiratory | No cough or production of sputum | New cough and/or productive cough of purulent sputum. Adventitious breath sounds (crackles, rhonchi, wheezing). New dyspnea. |

| Genitourinary | Urine clear, light yellow without odor | Malodorous, cloudy, bloody urine, with increased frequency, urgency, or pain with urination. |

| Gastrointestinal | Good appetite and food intake; feces formed and brown | Loss of appetite. Nausea and vomiting. Diarrhea; discolored or unusually malodorous feces. |

| *CRITICAL CONDITIONS requiring immediate notification of the provider and/or implementation of a sepsis protocol:

Two or more of the following criteria in a patient with an existing infection indicate SIRS:

|

Life Span Considerations

Infants do not have well-developed immune systems, placing this group at higher risk of infection. Breastfeeding helps protect infants from some infectious diseases by providing passive immunity until their immune system matures. New mothers should be encouraged to breastfeed their newborns.[66]

On the other end of the continuum, the immune system gradually decreases in effectiveness with age, making older adults also more vulnerable to infection. Early detection of infection can be challenging in older adults because they may not have a fever or increased white blood cell count (WBC), but instead develop subtle changes like new mental status changes.[67] The most common infections in older adults are urinary tract infections (UTI), bacterial pneumonia, influenza, and skin infections.

Diagnostic Tests

Several types of diagnostic tests may be ordered by a health care provider when a patient is suspected of having an infection, such as complete blood count with differential, Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR), C-Reactive Protein (CRP), serum lactate levels, and blood cultures (if sepsis is suspected). Other cultures may be obtained based on the site of the suspected infection.

CBC With Differential

When an infection is suspected, a complete blood count with differential is usually obtained.

A complete blood count (CBC) includes the red blood cell count (RBC), white blood cell count (WBC), platelets, hemoglobin, and hematocrit values. A differential provides additional information, including the relative percentages of each type of white blood cell. See Figure 9.22[68] for an illustration of a complete blood count with differential.

When there is an infection or an inflammatory process somewhere in the body, the bone marrow produces more WBCs (also called leukocytes), releasing them into the blood where they move to the site of infection or inflammation. An increase in white blood cells is known as leukocytosis and is a sign of the inflammatory response. The normal range of WBC varies slightly from lab to lab but is generally 4,500-11,000 for adults, reported as 4.5-11.0 x 109 per liter (L).[69]

There are five types of white blood cells, each with different functions. The differential blood count gives the relative percentage of each type of white blood cell and also reveals abnormal white blood cells. The five types of white blood cells are as follows:

- Neutrophils

- Eosinophils

- Basophils

- Lymphocytes

- Monocytes

Neutrophils make up the largest number of circulating WBCs. They move into an area of damaged or infected tissue where they engulf and destroy bacteria or sometimes fungi.[70] An elevated neutrophil count is called neutrophilia, and decreased neutrophil count is called neutropenia.[71]

Eosinophils respond to infections caused by parasites, play a role in allergic reactions (hypersensitivities), and control the extent of immune responses and inflammation. Elevated levels of eosinophils are referred to as eosinophilia.[72]

Basophils make up the fewest number of circulating WBCs and are thought to be involved in allergic reactions.[73]

Lymphocytes include three types of cells, although the differential count does not distinguish among them:

- B lymphocytes (B cells) produce antibodies that target and destroy bacteria, viruses, and other "non-self" foreign antigens.

- T lymphocytes (T cells) mature in the thymus and consist of a few different types. Some T cells help the body distinguish between "self" and "non-self" antigens; some initiate and control the extent of an immune response, boosting it as needed and then slowing it as the condition resolves; and other types of T cells directly attack and neutralize virus-infected or cancerous cells.

- Natural killer cells (NK cells) directly attack and kill abnormal cells such as cancer cells or those infected with a virus.[74]

Monocytes, similar to neutrophils, move to an area of infection and engulf and destroy bacteria. They are associated with chronic rather than acute infections. They are also involved in tissue repair and other functions involving the immune system.[75]

Care must be taken when interpreting the results of a differential. A health care provider will consider an individual's signs and symptoms and medical history, as well as the degree to which each type of cell is increased or decreased. A number of factors can cause a transient rise or drop in the number of any type of cell. For example, bacterial infections usually produce an increase in neutrophils, but a severe infection, like sepsis, can use up the available neutrophils, causing a low number to be found in the blood. Eosinophils are often elevated in parasitic and allergic responses. Acute viral infections often cause an increased level of lymphocytes (referred to as lymphocytosis).[76]

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR)

An erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is a test that indirectly measures inflammation. This test measures how quickly erythrocytes or red blood cells (RBCs) settle at the bottom of a test tube that contains a blood sample. When a sample of blood is placed in a tube, the red blood cells normally settle out relatively slowly, leaving a small amount of clear plasma. The red cells settle at a faster rate when there is an increased level of proteins, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), that increases in the blood in response to inflammation. The ESR test is not diagnostic; it is a nonspecific test indicating the presence or absence of an inflammatory condition.[77]

C-Reactive Protein (CRP)

C-Reactive Protein (CRP) levels in the blood increase when there is a condition causing inflammation somewhere in the body. CRP is a nonspecific indicator of inflammation and one of the most sensitive acute phase reactants, meaning it is released into the blood within a few hours after the start of an infection or other cause of inflammation. The level of CRP can jump as much as a thousand-fold in response to a severe bacterial infection, and its rise in the blood can precede symptoms of fever or pain.[78]

Lactate

Serum lactate levels are measured when sepsis is suspected in a patient with an existing infection. Sepsis can quickly lead to septic shock and death due to multi-organ failure so early recognition is crucial.

Lactate is one of the substances produced by cells as the body turns food into energy (i.e., cellular metabolism), with the highest level of production occurring in the muscles. Normally, the level of lactate in blood is low. Lactate is produced in excess by muscle cells and other tissues when there is insufficient oxygen at the cellular level.

Lactic acid can accumulate in the body and blood when it is produced faster than the liver can break it down, which can lead to lactic acidosis. Excess lactate may be produced due to several medical conditions that cause decreased transport of oxygen to the tissues, such as sepsis, hypovolemic shock, heart attack, heart failure, or respiratory distress.[79]

Blood Culture

Blood cultures are ordered when sepsis is suspected. In many facilities, lab personnel draw the blood samples for blood cultures to avoid contamination of the sample. With some infections, pathogens are only found in the blood intermittently, so a series of three or more blood cultures, as well as blood draws from different veins, may be performed to increase the chance of finding the infection.

Blood cultures are incubated for several days before being reported as negative. Some types of bacteria and fungi grow more slowly than others and/or may take longer to detect if initially present in low numbers.

A positive result indicates bacteria have been found in the blood (bacteremia). Other types of pathogens, such as a fungus or a virus, may also be found in a blood culture. When a blood culture is positive, the specific microbe causing the infection is identified and susceptibility testing is performed to inform the health care provider which antibiotics or other medications are most likely to be effective for treatment.