3.2 Blood Pressure Basics

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

What is Blood Pressure?

A blood pressure reading is the measurement of the force of blood against the walls of the arteries as the heart pumps blood through the body. It is reported in millimeters of mercury (mmHg). This pressure changes in the arteries when the heart is contracting compared to when it is resting and filling with blood. Blood pressure is typically expressed as the reflection of two numbers, systolic pressure and diastolic pressure. The systolic blood pressure is the maximum pressure on the arteries during systole, the phase of the heartbeat when the ventricles contract. Systole causes the ejection of blood out of the ventricles and into the aorta and pulmonary arteries. The diastolic blood pressure is the resting pressure on the arteries during diastole, the phase between each contraction of the heart when the ventricles are filling with blood.[1]

Blood pressure measurements are obtained using a stethoscope and a sphygmomanometer, also called a blood pressure cuff. To obtain a manual blood pressure reading, the blood pressure cuff is placed around a patient’s extremity, and a stethoscope is placed over an artery. For most blood pressure readings, the cuff is usually placed around the upper arm, and the stethoscope is placed over the brachial artery. The cuff is inflated to constrict the artery until the pulse is no longer palpable, and then it is deflated slowly. The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends that the blood pressure cuff be inflated at least 30 mmHg above the point at which the radial pulse is no longer palpable. The first appearance of sounds, called Korotkoff sounds, are noted as the systolic blood pressure reading. Korotkoff sounds are named after Dr. Korotkoff, who first discovered the audible sounds of blood pressure when the arm is constricted.[2] The blood pressure cuff continues to be deflated until Korotkoff sounds disappear. The last Korotkoff sounds reflect the diastolic blood pressure reading.[3] It is important to deflate the cuff slowly at no more than 2-3 mmHg per second to ensure that the absence of pulse is noted promptly and that the reading is accurate. Blood pressure readings are documented as systolic blood pressure/diastolic pressure, for example, 120/80 mmHg.

Abnormal blood pressure readings can signify an area of concern and a need for intervention. Normal adult blood pressure is less than 120/80 mmHg. Hypertension is the medical term for elevated blood pressure readings of 130/80 mmHg or higher. See Table 4.2 for blood pressure categories according to the 2017 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association Blood Pressure Guidelines.[4] Prior to diagnosing a person with hypertension, the health care provider will calculate an average blood pressure based on two or more blood pressure readings obtained on two or more occasions.

Hypotension is the medical term for low blood pressure readings less than 90/60 mmHg.[5] Hypotension can be caused by dehydration, bleeding, cardiac conditions, and the side effects of many medications. Hypotension can be of significant concern because of the potential lack of perfusion to critical organs when blood pressures are low. Orthostatic hypotension is a drop in blood pressure that occurs when moving from a lying down (supine) or seated position to a standing (upright) position. When measuring blood pressure, orthostatic hypotension is defined as a decrease in blood pressure by at least 20 mmHg systolic or 10 mmHg diastolic within three minutes of standing. When a person stands, gravity moves blood from the upper body to the lower limbs. As a result, there is a temporary reduction in the amount of blood in the upper body for the heart to pump, which decreases blood pressure. Normally, the body quickly counteracts the force of gravity and maintains stable blood pressure and blood flow. In most people, this transient drop in blood pressure goes unnoticed. However, some patients with orthostatic hypotension can experience light-headedness, dizziness, or fainting. This is a significant safety concern because of the increased risk of falls and injury, particularly in older adults.[6]

Table 4.2 Blood Pressure Categories[7]

| Blood Pressure Category | Systolic mm Hg (upper #) | Diastolic mm Hg (lower #) |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | < 120 | < 80 |

| Stage 1 | 130-139 | 80-89 |

| Stage 2 | At least 140 | At least 90 |

| Hypertensive Crisis | > 180 | > 120 |

View Ahmend Alzawi’s Korotkoff Sounds Video on YouTube[8]

Equipment to Measure Blood Pressure

Manual Blood Pressure

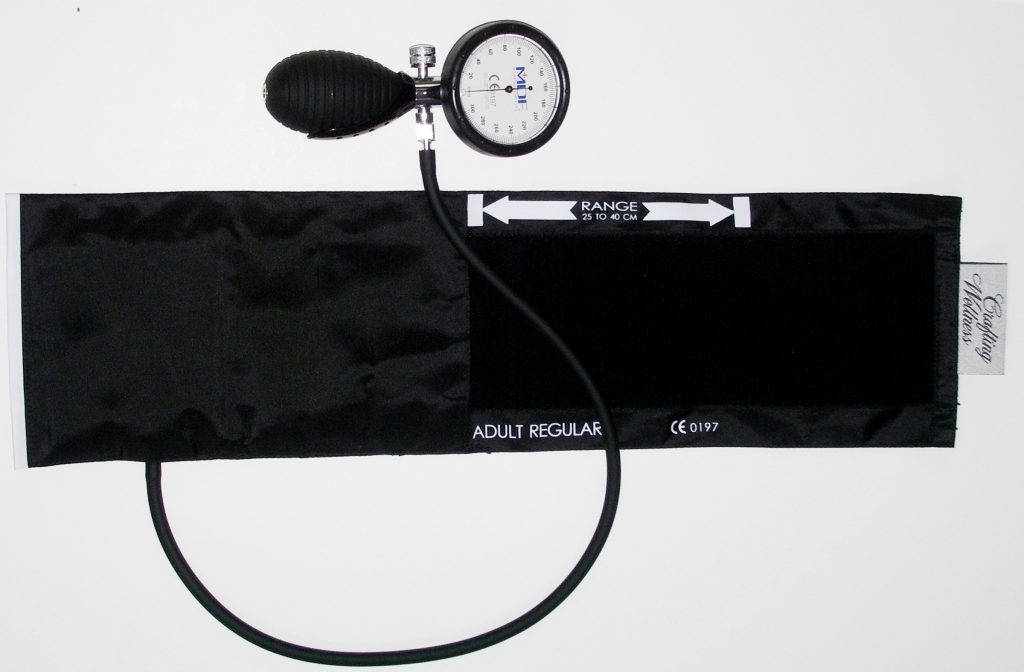

A sphygmomanometer, commonly called a blood pressure cuff, is used to measure blood pressure while Korotkoff sounds are auscultated using a stethoscope. See Figure 3.1[9] for an image of a sphygmomanometer.

There are various sizes of blood pressure cuffs. It is crucial to select the appropriate size for the patient to obtain an accurate reading. An undersized cuff will cause an artificially high blood pressure reading, and an oversized cuff will produce an artificially low reading. See Figure 3.2[10] for an image of various sizes of blood pressure cuffs ranging in size for a large adult to an infant.

The width of the cuff should be 40% of the person’s arm circumference, and the length of the cuff’s bladder should be 80–100% of the person’s arm circumference. Keep in mind that only about half of the blood pressure cuff is the bladder and the other half is cloth with a hook and loop fastener to secure it around the arm.

View Ryerson University’s Accurate Blood Pressure Cuff Sizing Video on YouTube[11]

Automatic Blood Pressure Equipment

Automatic blood pressure monitors are often used in health care settings to efficiently measure blood pressure for multiple patients or to repeatedly measure a single patient’s blood pressure at a specific frequency such as every 15 minutes. See Figure 3.3 [12] for an image of an automatic blood pressure monitor. To use an automatic blood pressure monitor, appropriately position the patient and place the correctly sized blood pressure cuff on their bare arm or other extremity. Press the start button on the monitor. The cuff will automatically inflate and then deflate at a rate of 2 mmHg per second. The monitor digitally displays the blood pressure reading when done. If the blood pressure reading is unexpected, it is important to follow up by obtaining a reading using a manual blood pressure cuff. Additionally, automatic blood pressure monitors should not be used if the patient has a rapid or irregular heart rhythm, such as atrial fibrillation, or has tremors as it may lead to an inaccurate reading.

- This work is a derivative of Vital Sign Measurement Across the Lifespan - 1st Canadian Edition by Ryerson University licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Campbell and Pillarisetty licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- American College of Cardiology. Whelton, P. K., Carey, R. M., Aronow, W. S.., et al. (2018, May 7). 2017 guidelines for high blood pressure in adults. https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/ten-points-to-remember/2017/11/09/11/41/2017-guideline-for-high-blood-pressure-in-adults ↵

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (n.d.). Low blood pressure. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/low-blood-pressure ↵

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. (2020, June 23). Orthostatic hypotension. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/orthostatic-hypotension ↵

- American College of Cardiology. Whelton, P. K., Carey, R. M., Aronow, W. S.., et al. (2018, May 7). 2017 guidelines for high blood pressure in adults. https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/ten-points-to-remember/2017/11/09/11/41/2017-guideline-for-high-blood-pressure-in-adults ↵

- Alzawi, A. (2015, November 19). Korotkoff+Blood+Pressure+Sights+and+Sounds SD. [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/UfCr_wUepxo ↵

- “Sphygmomanometer&Cuff.JPG” by ML5 is in the Public Domain ↵

- “BP-Multiple-Cuff-Sizes.jpg” by British Columbia Institute of Technology (BCIT) is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://opentextbc.ca/vitalsign/chapter/how-is-blood-pressure-measured/ ↵

- Ryerson University. (2018, March 21). Blood pressure - Accurate cuff sizing. [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/uNTMwoJTfFE ↵

- “Automatische bloeddrukmeter (0).jpg” by Harmid is in the Public Domain ↵

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

1. During a musculoskeletal assessment, the nurse has the patient simultaneously resist against exerted force with both upper extremities. The nurse knows this it is important to perform this assessment on both extremities simultaneously for what reason?

- It measures muscle strength symmetry.

- It provides a more accurate reading.

- It involves more muscle use.

- It decreases assessment time.

2. The nurse is testing upper body strength on an adolescent. The test indicates full ROM against gravity and full resistance. How does the nurse document these assessment findings according to the muscle strength scale?

- 4 out of 5

- 3 out of 5

- 5 out of 5

- 1 out of 5

3. A young adult presents to the urgent care with a right knee injury. The injury occurred during a basketball game. The nurse begins to perform a musculoskeletal assessment. What is the first step of the assessment?

- Palpation

- Inspection

- Percussion

- Auscultation

Abduction: Joint movement away from the midline of the body.

Active range of motion: The degree of movement a patient can voluntarily achieve in a joint without assistance.

Adduction: Joint movement toward the middle line of the body.

Arthroplasty: Joint replacement surgery.

Arthroscopic surgery: A surgical procedure involving a small incision and the insertion of an arthroscope, a pencil-thin instrument that allows for visualization of the joint interior. Small surgical instruments are inserted via additional incisions to remove or repair ligaments and other joint structures.

Articular cartilage: Smooth, white tissue that covers the ends of bones where they come together at joints, allowing them to glide over each other with very little friction. Articular cartilage can be damaged by injury or normal wear and tear.

Clubfoot: A congenital condition that causes the foot and lower leg to turn inward and downward.

Congenital condition: A condition present at birth.

Contracture: A fixed or permanent tightening of muscles, tendons, ligaments, or the skin that prevents normal movement of the body part.

Crepitus: A crackling, popping noise heard on joint movement. It is considered normal when it is not associated with pain.

Dislocation: A joint injury that forces the ends of bones out of position; often caused by a fall or a blow to the joint.

Extension: Joint movement causing the straightening of limbs (increase in angle) at a joint.

Flexion: Joint movement causing the bending of the limbs (reduction of angle) at a joint.

Foot drop: The inability to raise the front part of the foot due to weakness or paralysis of the muscles that lift the foot.

Fracture: A broken bone.

Gout: A type of arthritis that causes swollen, red, hot, and stiff joints due to the buildup of uric acid, commonly starting in the big toe.

Joints: The location where bones come together.

Kyphosis: A curving of the spine that causes a bowing or rounding of the back, leading to a hunchback or slouching posture.

Ligaments: Strong bands of fibrous connective tissue that connect bones and strengthen and support joints by anchoring bones together and preventing their separation.

Lordosis: An inward curve of the lumbar spine just above the buttocks. A small degree of lordosis is normal, but too much curving is called swayback.

Muscle atrophy: The thinning or loss of muscle tissue that can be caused by disuse, aging, or neurological damage.

Open fracture: A type of fracture when the broken bone punctures the skin.

Osteoarthritis: The most common type of arthritis associated with aging and wear and tear of the articular cartilage that covers the surfaces of bones at the synovial joint.

Osteoporosis: A disease that thins and weakens bones, especially in the hip, spine, and wrist, causing them to become fragile and break easily.

Passive range of motion: The degree of range of motion a patient demonstrates in a joint when the examiner is providing the movement.

Rheumatoid arthritis: A type of arthritis that causes pain, swelling, stiffness, and loss of function in joints due to inflammation caused by an autoimmune disease.

RICE: A mnemonic for treatment of sprains and strains that stands for: Resting the injured area, Icing the area, Compressing the area with an ACE bandage or other device, and Elevating the affected limb.

Rotation: Circular movement of a joint around a fixed point.

Scoliosis: A sideways curve of the spine that commonly develops in late childhood and the early teens.

Skeletal muscle: Voluntary muscle that produces movement, assists in maintaining posture, protects internal organs, and generates body heat.

Sprain: A stretched or torn ligament caused by an injury.

Strain: A stretched or torn muscle or tendon.

Synovial fluid: A thick fluid that provides lubrication in joints to reduce friction between the bones.

Synovial joints: A fluid-filled joint cavity where the articulating surfaces of the bones contact and move smoothly against each other. The elbow and knee are examples of synovial joints.

Tendons: Strong bands of dense, regular connective tissue that connect muscles to bones.

Abduction: Joint movement away from the midline of the body.

Active range of motion: The degree of movement a patient can voluntarily achieve in a joint without assistance.

Adduction: Joint movement toward the middle line of the body.

Arthroplasty: Joint replacement surgery.

Arthroscopic surgery: A surgical procedure involving a small incision and the insertion of an arthroscope, a pencil-thin instrument that allows for visualization of the joint interior. Small surgical instruments are inserted via additional incisions to remove or repair ligaments and other joint structures.

Articular cartilage: Smooth, white tissue that covers the ends of bones where they come together at joints, allowing them to glide over each other with very little friction. Articular cartilage can be damaged by injury or normal wear and tear.

Clubfoot: A congenital condition that causes the foot and lower leg to turn inward and downward.

Congenital condition: A condition present at birth.

Contracture: A fixed or permanent tightening of muscles, tendons, ligaments, or the skin that prevents normal movement of the body part.

Crepitus: A crackling, popping noise heard on joint movement. It is considered normal when it is not associated with pain.

Dislocation: A joint injury that forces the ends of bones out of position; often caused by a fall or a blow to the joint.

Extension: Joint movement causing the straightening of limbs (increase in angle) at a joint.

Flexion: Joint movement causing the bending of the limbs (reduction of angle) at a joint.

Foot drop: The inability to raise the front part of the foot due to weakness or paralysis of the muscles that lift the foot.

Fracture: A broken bone.

Gout: A type of arthritis that causes swollen, red, hot, and stiff joints due to the buildup of uric acid, commonly starting in the big toe.

Joints: The location where bones come together.

Kyphosis: A curving of the spine that causes a bowing or rounding of the back, leading to a hunchback or slouching posture.

Ligaments: Strong bands of fibrous connective tissue that connect bones and strengthen and support joints by anchoring bones together and preventing their separation.

Lordosis: An inward curve of the lumbar spine just above the buttocks. A small degree of lordosis is normal, but too much curving is called swayback.

Muscle atrophy: The thinning or loss of muscle tissue that can be caused by disuse, aging, or neurological damage.

Open fracture: A type of fracture when the broken bone punctures the skin.

Osteoarthritis: The most common type of arthritis associated with aging and wear and tear of the articular cartilage that covers the surfaces of bones at the synovial joint.

Osteoporosis: A disease that thins and weakens bones, especially in the hip, spine, and wrist, causing them to become fragile and break easily.

Passive range of motion: The degree of range of motion a patient demonstrates in a joint when the examiner is providing the movement.

Rheumatoid arthritis: A type of arthritis that causes pain, swelling, stiffness, and loss of function in joints due to inflammation caused by an autoimmune disease.

RICE: A mnemonic for treatment of sprains and strains that stands for: Resting the injured area, Icing the area, Compressing the area with an ACE bandage or other device, and Elevating the affected limb.

Rotation: Circular movement of a joint around a fixed point.

Scoliosis: A sideways curve of the spine that commonly develops in late childhood and the early teens.

Skeletal muscle: Voluntary muscle that produces movement, assists in maintaining posture, protects internal organs, and generates body heat.

Sprain: A stretched or torn ligament caused by an injury.

Strain: A stretched or torn muscle or tendon.

Synovial fluid: A thick fluid that provides lubrication in joints to reduce friction between the bones.

Synovial joints: A fluid-filled joint cavity where the articulating surfaces of the bones contact and move smoothly against each other. The elbow and knee are examples of synovial joints.

Tendons: Strong bands of dense, regular connective tissue that connect muscles to bones.

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of "Applying and Removing Sterile Gloves.”

Video Review of Applying Sterile Gloves:[1]

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Gather the supplies: hand sanitizer and sterile gloves.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Open the sterile gloves on a dry, flat, clean work surface.

- Remove the outer package by separating and peeling apart the sides of the package.

- Grasp the inner package and lay it on a clean, dry, flat surface at waist level.

- Open the top flap away from your body; open the bottom flap toward your body.

- Open the side flaps without contaminating the inside of the wrapper or allowing it to close.

- With your nondominant hand, use your thumb and index finger to only grasp the inside surface of the cuff of the glove for your dominant hand.

- Lift out the glove, being careful to not touch any surfaces and holding the glove no more than 12-18" above the table without contaminating the sterile glove; carefully pull the glove over your hand.

- Use your nondominant, nonsterile hand to grasp the flap of the package, and hold the package steady. With the sterile glove on your dominant hand, hold 4 fingers together of the gloved hand to reach in the outer surface of the cuff of the sterile glove, reaching under the folded cuff and with the thumb outstretched to not touch the second sterile glove. Lift the glove off the package without breaking sterility.

- While holding the fingers of the nondominant hand outstretched and close together, tuck your thumb into the palm, and use the sterile dominant hand to pull the second sterile glove over the fingers of the nondominant hand.

- After the second sterile glove is on, interlock the fingers of your sterile gloved hands, being careful to keep your hands above your waist.

- Do not touch the inside of the package or the sterile part of the gloves with your bare hands during the process.

- Maintain sterility throughout the procedure of donning sterile gloves.

Removing Sterile Gloves

- Grasp the outside of one cuff with the other gloved hand. Avoid touching your skin.

- Pull the glove off, turning it inside out and gather it in the palm of the gloved hand.

- Tuck the index finger of your bare hand inside the remaining glove cuff and peel the glove off inside out and over the previously removed glove.

- Dispose of contaminated wastes appropriately.

- Perform hand hygiene.

Learning Objectives

- Perform an integumentary assessment including the skin, hair, and nails

- Modify assessment techniques to reflect variations across the life span and ethnic and cultural variations

- Document actions and observations

- Recognize and report significant deviations from norms

Assessing the skin, hair, and nails is part of a routine head-to-toe assessment completed by registered nurses. During inpatient care, a comprehensive skin assessment on admission establishes a baseline for the condition of a patient’s skin and is essential for developing a care plan for the prevention and treatment of skin injuries.[2] Before discussing the components of a routine skin assessment, let’s review the anatomy of the skin and some common skin and hair conditions.

Learning Objectives

- Perform an integumentary assessment including the skin, hair, and nails

- Modify assessment techniques to reflect variations across the life span and ethnic and cultural variations

- Document actions and observations

- Recognize and report significant deviations from norms

Assessing the skin, hair, and nails is part of a routine head-to-toe assessment completed by registered nurses. During inpatient care, a comprehensive skin assessment on admission establishes a baseline for the condition of a patient’s skin and is essential for developing a care plan for the prevention and treatment of skin injuries.[3] Before discussing the components of a routine skin assessment, let’s review the anatomy of the skin and some common skin and hair conditions.