14.4 Integumentary Assessment

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Now that we have reviewed the anatomy of the integumentary system and common integumentary conditions, let’s review the components of an integumentary assessment. The standard for documentation of skin assessment is within 24 hours of admission to inpatient care. Skin assessment should also be ongoing in inpatient and long-term care.[1]

A routine integumentary assessment by a registered nurse in an inpatient care setting typically includes inspecting overall skin color, inspecting for skin lesions and wounds, and palpating extremities for edema, temperature, and capillary refill.[2]

Subjective Assessment

Begin the assessment by asking focused interview questions regarding the integumentary system. Itching is the most frequent complaint related to the integumentary system. See Table 14.4a for sample interview questions.

Table 14.4a Focused Interview Questions for the Integumentary System

| Questions | Follow-up |

|---|---|

| Are you currently experiencing any skin symptoms such as itching, rashes, or an unusual mole, lump, bump, or nodule?[3] | Use the PQRSTU method to gain additional information about current symptoms. Read more about the PQRSTU method in the “Health History” chapter. |

| Have you ever been diagnosed with a condition such as acne, eczema, skin cancer, pressure injuries, jaundice, edema, or lymphedema? | Please describe. |

| Are you currently using any prescription or over-the-counter medications, creams, vitamins, or supplements to treat a skin, hair, or nail condition? | Please describe. |

Objective Assessment

There are five key areas to note during a focused integumentary assessment: color, skin temperature, moisture level, skin turgor, and any lesions or skin breakdown. Certain body areas require particular observation because they are more prone to pressure injuries, such as bony prominences, skin folds, perineum, between digits of the hands and feet, and under any medical device that can be removed during routine daily care.[4]

Inspection

Color

Inspect the color of the patient’s skin and compare findings to what is expected for their skin tone. Note a change in color such as pallor (paleness), cyanosis (blueness), jaundice (yellowness), or erythema (redness). Note if there is any bruising (ecchymosis) present.

Scalp

If the patient reports itching of the scalp, inspect the scalp for lice and/or nits.

Lesions and Skin Breakdown

Note any lesions, skin breakdown, or unusual findings, such as rashes, petechiae, unusual moles, or burns. Be aware that unusual patterns of bruising or burns can be signs of abuse that warrant further investigation and reporting according to agency policy and state regulations.

Auscultation

Auscultation does not occur during a focused integumentary exam.

Palpation

Palpation of the skin includes assessing temperature, moisture, texture, skin turgor, capillary refill, and edema. If erythema or rashes are present, it is helpful to apply pressure with a gloved finger to further assess for blanching (whitening with pressure).

Temperature, Moisture, and Texture

Fever, decreased perfusion of the extremities, and local inflammation in tissues can cause changes in skin temperature. For example, a fever can cause a patient’s skin to feel warm and sweaty (diaphoretic). Decreased perfusion of the extremities can cause the patient’s hands and feet to feel cool, whereas local tissue infection or inflammation can make the localized area feel warmer than the surrounding skin. Research has shown that experienced practitioners can palpate skin temperature accurately and detect differences as small as 1 to 2 degrees Celsius. For accurate palpation of skin temperature, do not hold anything warm or cold in your hands for several minutes prior to palpation. Use the palmar surface of your dominant hand to assess temperature.[5] While assessing skin temperature, also assess if the skin feels dry or moist and the texture of the skin. Skin that appears or feels sweaty is referred to as being diaphoretic.

Capillary Refill

The capillary refill test is a test done on the nail beds to monitor perfusion, the amount of blood flow to tissue. Pressure is applied to a fingernail or toenail until it turns white, indicating that the blood has been forced from the tissue under the nail. This whiteness is called blanching. Once the tissue has blanched, remove pressure. Capillary refill is defined as the time it takes for color to return to the tissue after pressure has been removed that caused blanching. If there is sufficient blood flow to the area, a pink color should return within 2 seconds after the pressure is removed. [6]

Skin Turgor

Skin turgor may be included when assessing a patient’s hydration status, but research has shown it is not a good indicator. Skin turgor is the skin’s elasticity. Its ability to change shape and return to normal may be decreased when the patient is dehydrated. To check for skin turgor, gently grasp skin on the patient’s lower arm between two fingers so that it is tented upwards, and then release. Skin with normal turgor snaps rapidly back to its normal position, but skin with poor turgor takes additional time to return to its normal position.[8] Skin turgor is not a reliable method to assess for dehydration in older adults because they have decreased skin elasticity, so other assessments for dehydration should be included.[9]

Edema

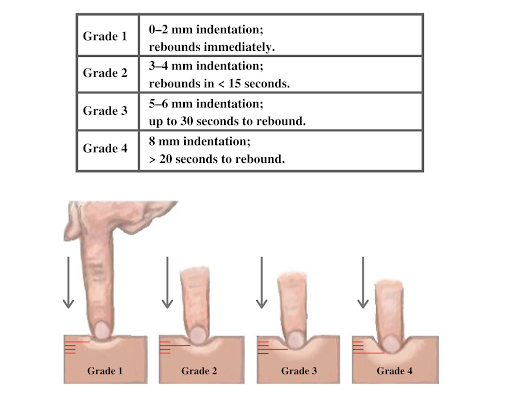

If edema is present on inspection, palpate the area to determine if the edema is pitting or nonpitting. Press on the skin to assess for indentation, ideally over a bony structure, such as the tibia. If no indentation occurs, it is referred to as nonpitting edema. If indentation occurs, it is referred to as pitting edema. See Figure 14.22[10] for an image demonstrating pitting edema. If pitting edema is present, document the depth of the indention and how long it takes for the skin to rebound back to its original position. The indentation and time required to rebound to the original position are graded on a scale from 1 to 4, where 1+ indicates a barely detectable depression with immediate rebound, and 4+ indicates a deep depression with a time lapse of over 20 seconds required to rebound. See Figure 14.23[11] for an illustration of grading edema.

Life Span Considerations

Older Adults

Older adults have several changes associated with aging that are apparent during assessment of the integumentary system. They often have cardiac and circulatory system conditions that cause decreased perfusion, resulting in cool hands and feet. They have decreased elasticity and fragile skin that often tears more easily. The blood vessels of the dermis become more fragile, leading to bruising and bleeding under the skin. The subcutaneous fat layer thins, so it has less insulation and padding and reduced ability to maintain body temperature. Growths such as skin tags, rough patches (keratoses), skin cancers, and other lesions are more common. Older adults may also be less able to sense touch, pressure, vibration, heat, and cold.[12]

When completing an integumentary assessment it is important to distinguish between expected and unexpected assessment findings. Please review Table 14.4b to review common expected and unexpected integumentary findings.

Table 14.4b Expected Versus Unexpected Findings on integumentary Assessment

| Assessment | Expected Findings | Unexpected Findings (Document and notify provider if it is a new finding*) |

|---|---|---|

| Inspection | Skin is expected color for ethnicity without lesions or rashes. | Jaundice

Erythema Cyanosis Irregular-looking mole Bruising (ecchymosis) Rashes Petechiae Skin breakdown Burns |

| Auscultation | Not applicable | |

| Palpation | Skin is warm and dry with no edema. Capillary refill is less than 3 seconds. Skin has normal turgor with no tenting. | Diaphoretic or clammy

Cool extremity Edema Lymphedema Capillary refill greater than 3 seconds Tenting |

| *CRITICAL CONDITIONS to report immediately | Cool and clammy

Diaphoretic Petechiae Jaundice Cyanosis Redness, warmth, and tenderness indicating a possible infection |

- Medline Industries, Inc. (n.d.). Are you doing comprehensive skin assessments correctly? Get the whole picture. https://www.medline.com/skin-health/comprehensive-skin-assessments-correctly-get-whole-picture/#:~:text=A%20comprehensive%20skin%20assessment%20entails,actually%20more%20than%20skin%20deep. ↵

- Giddens, J. F. (2007). A survey of physical examination techniques performed by RNs: Lessons for nursing education. Journal of Nursing Education, 46(2), 83-87. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20070201-09 ↵

- McKay, M. (1990). The dermatologic history. In Walker, H. K., Hall, W. D., Hurst, J. W. (Eds.), Clinical methods: The history, physical, and laboratory examinations (3rd ed.). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207/ ↵

- Medline Industries, Inc. (n.d.). Are you doing comprehensive skin assessments correctly? Get the whole picture. https://www.medline.com/skin-health/comprehensive-skin-assessments-correctly-get-whole-picture/#:~:text=A%20comprehensive%20skin%20assessment%20entails,actually%20more%20than%20skin%20deep. ↵

- Levine, D., Walker, J. R., Marcellin-Little, D. J., Goulet, R., & Ru, H. (2018). Detection of skin temperature differences using palpation by manual physical therapists and lay individuals. The Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy, 26(2), 97-101. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F10669817.2018.1427908 ↵

- Johannsen, L.L. (2005). Skin assessment. Dermatology Nursing, 17(2), 165-66. ↵

- Nurse Saria. (2018, September 18). Cardiovascular assessment part two | Capillary refill test. [Video}. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/A6htMxo4Cks ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2020. Skin turgor; [updated 2020, Sep 16; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003281.htm#:~:text=To%20check%20for%20skin%20turgor,back%20to%20its%20normal%20position. ↵

- Nursing Times. (2015, August 3). Detecting dehydration in older people. https://www.nursingtimes.net/roles/older-people-nurses-roles/detecting-dehydration-in-older-people-useful-tests-03-08-2015/ ↵

- “Combinpedal.jpg” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “Grading of Edema” by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2020. Aging changes in skin; [updated 2020, Sep 16; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/004014.htm#:~:text=The%20remaining%20melanocytes%20increase%20in,the%20skin's%20strength%20and%20elasticity ↵

Airborne precautions: Infection prevention and control interventions to be used in addition to standard precautions for diseases spread by airborne transmission, such as measles and tuberculosis.

Asepsis: A state of being free of disease-causing microorganisms.

Aseptic non-touch technique: A standardized technique, supported by evidence, to maintain asepsis and standardize practice.

Aseptic technique (medical asepsis): The purposeful reduction of pathogen numbers while preventing microorganism transfer from one person or object to another. This technique is commonly used to perform invasive procedures, such as IV starts or urinary catheterization.

Contact precautions: Infection prevention and control interventions to be used in addition to standard precautions for diseases spread by contact with the patient, their body fluids, or their surroundings, such as C-diff, MRSA, VRE, and RSV.

Doff: To take off or remove personal protective equipment, such as gloves or a gown.

Don: To put on equipment for personal protection, such as gloves or a gown.

Droplet precautions: Infection prevention and control interventions to be used in addition to standard precautions; used for diseases spread by large respiratory droplets such as influenza, COVID-19, or pertussis.

Five moments of hand hygiene: Hand hygiene should be performed during the five moments of patient care: immediately before touching a patient; before performing an aseptic task or handling invasive devices; before moving from a soiled body site to a clean body site on a patient; after touching a patient or their immediate environment; after contact with blood, body fluids, or contaminated surfaces (with or without glove use); and immediately after glove removal.

Hand hygiene: A way of cleaning one’s hands to substantially reduce the number of pathogens and other contaminants (e.g., dirt, body fluids, chemicals, or other unwanted substances) to prevent disease transmission or integumentary harm, typically using soap, water, and friction. An alcohol-based hand rub solution may be appropriate hand hygiene for hands not visibly soiled.

Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs): Unintended infections caused by care received in a health care setting.

Key part: Any sterile part of equipment used during an aseptic procedure, such as needle hubs, syringe tips, dressings, etc.

Key site: The site contacted during an aseptic procedure, such as nonintact skin, a potential insertion site, or an access site used for medical devices connected to the patients. Examples of key sites include the insertion or access site for intravenous (IV) devices, urinary catheters, and open wounds.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Personal protective equipment, such as gloves, gowns, face shields, goggles, and masks, used to prevent transmission of disease from patient to patient, patient to health care provider, and health care provider to patient.

Standard precautions: The minimum infection prevention practices that apply to all patient care, regardless of suspected or confirmed infection status of the patient, in any setting where health care is delivered.

Sterile technique (surgical asepsis): Techniques used to eliminate every potential microorganism in and around a sterile field while maintaining objects and areas as free from microorganisms as possible. This technique is the standard of care for surgical procedures, invasive wound management, and central line care.

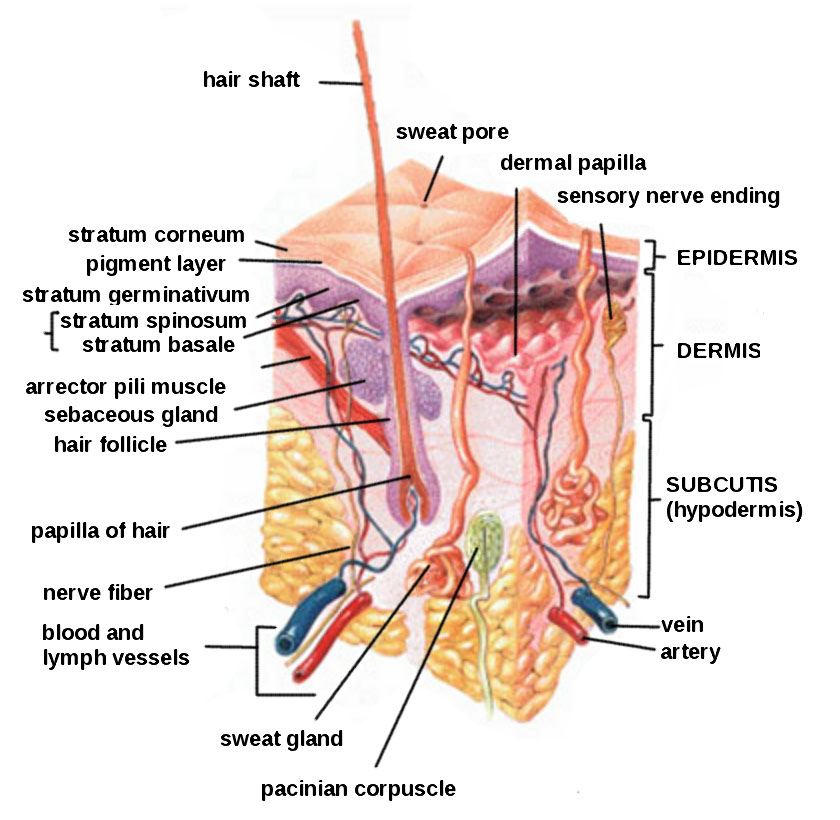

Subcutaneous injections are administered into the adipose tissue layer called “subcutis” below the dermis. See an image of the subcutis (hypodermis) layer in Figure 18.20.[1] Medications injected into the subcutaneous layer are absorbed at a slow and steady rate.

Anatomic Sites

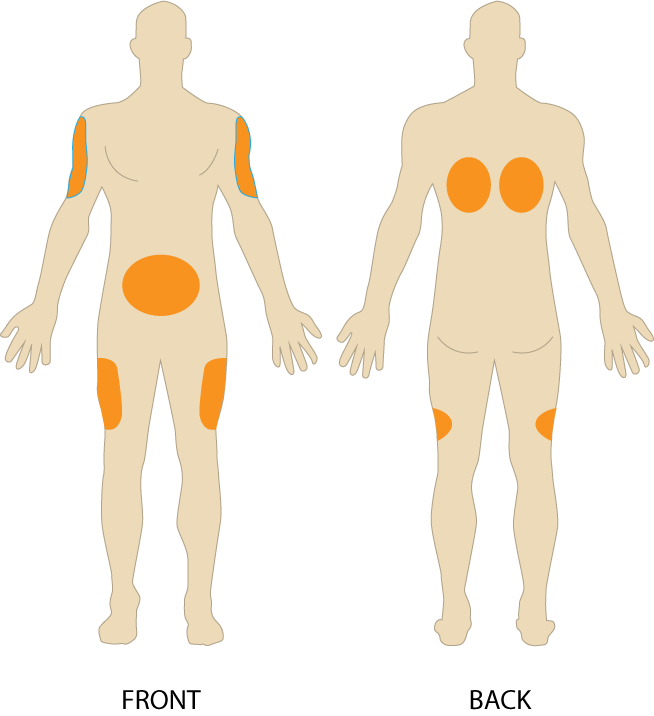

Sites for subcutaneous injections include the outer lateral aspect of the upper arm, the abdomen (from below the costal margin to the iliac crest and more than two inches from the umbilicus), the anterior upper thighs, the upper back, and the upper ventral gluteal area.[2] See Figure 18.21[3] for an illustration of commonly used subcutaneous injection sites. These areas have large surface areas that allow for rotation of subcutaneous injections within the same site when applicable.

Prior to injecting the medication, inspect the skin area. Avoid skin areas that are bruised, open, scarred, or over bony prominences. Medical conditions that impair the blood flow to a tissue area contraindicate the use of subcutaneous injections in that area. For example, if a patient has an infection in an area of their skin called “cellulitis,” then subcutaneous injections should not be given in that area.

Description of Procedure

Nurses select the appropriate needle size for subcutaneous injection based on patient size. Subcutaneous needles range in gauge from 25-31 and in length from ½ inch to ⅝ inch. Prior to administering the injection, determine the amount of subcutaneous tissue present and use this information to select the needle length. A 45- or 90-degree angle is used for a subcutaneous injection. A 90-degree angle is used for normal-sized adult patients or obese patients, and a 45-degree angle is used for patients who are thin or have with less adipose tissue at the injection site. The volume of solution in a subcutaneous injection should be no more than 1 mL for adults and 0.5 mL for children. Larger amounts may not be absorbed appropriately and may cause increased discomfort for the patient.[4]

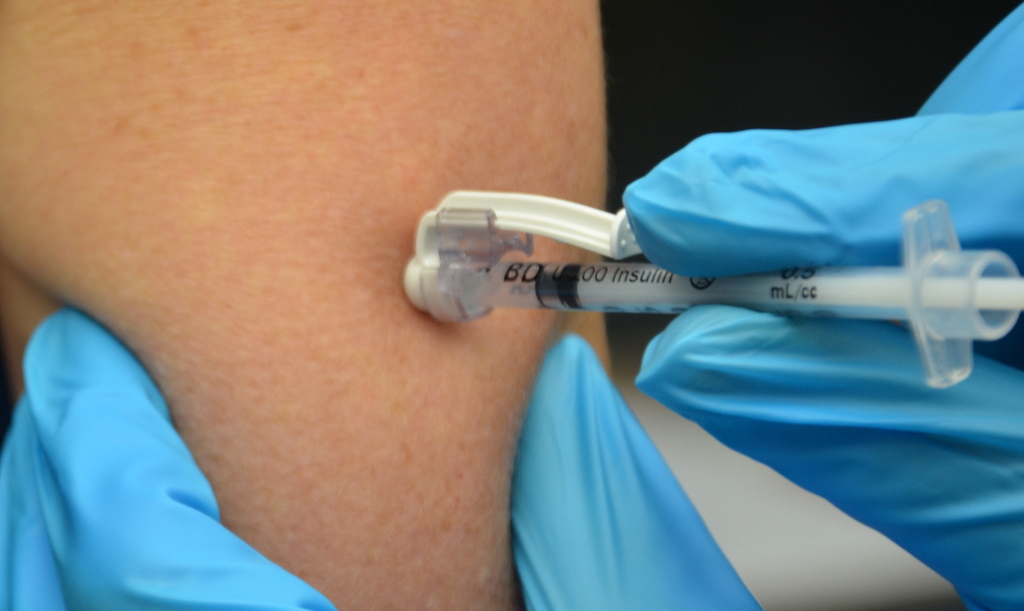

When administering a subcutaneous injection, assess the patient for any contraindications for receiving the medication. Apply nonsterile gloves after performing hand hygiene to reduce your risk of exposure to blood. Position the patient in a comfortable position and select an appropriate site for injection. Cleanse the site with an alcohol swab or antiseptic swab for 30 seconds using a firm, circular motion, and then allow the site to dry. Allowing the skin to dry prevents introducing alcohol into the tissue, which can be irritating and uncomfortable. Remove the needle cap with the nondominant hand, pulling it straight off to avoid needlestick injury. Grasp and pinch the area selected as an injection site.[5] See Figure 18.22[6] for an image of a nurse grasping the back of a patient’s upper arm with the nondominant hand in preparation of a subcutaneous injection at the anatomical site indicted with an “X.”

Hold the syringe in the dominant hand between the thumb and forefinger like a dart. Insert the needle quickly at a 45- to 90-degree angle, depending on the size of the patient and the amount of adipose tissue. After the needle is in place, release the tissue with your nondominant hand. With your dominant hand, inject the medication at a rate of 10 seconds per mL. Avoid moving the syringe.[7] See Figure 18.23[8] for an image of a subcutaneous injection.

Withdraw the needle quickly at the same angle at which it was inserted. Using a sterile gauze, apply gentle pressure at the site after the needle is withdrawn. Do not massage the site. Massaging after a heparin injection can contribute to the formation of a hematoma. Do not recap the needle to avoid puncturing oneself. Apply the safety shield and dispose of the syringe/needle in a sharps container. See Figure 18.24[9] for an image of a needle after the safety shield has been applied. Remove gloves and perform hand hygiene.[10]

Examples of common medications administered via subcutaneous injection include insulin and heparin. Special considerations for each of these medications are discussed below.

Insulin Injections

Insulin is considered a high-alert medication requiring special care to prevent medication errors. Care must be taken to ensure the correct type and amount of insulin are administered at the correct time. It is highly recommended to have insulin dosages double-checked by another nurse before administration because of the potential for life-threatening adverse effects that can occur due to medication errors. Some agencies require this second safety check.

Only insulin syringes should be used to administer insulin injection. Insulin syringes are supplied in 30-, 50-, or 100-unit measurements, so read the barrel increments (calibration) carefully. Insulin is always ordered and administered in unit dosage. Insulin dosage may be based on the patient’s pre-meal blood sugar reading and a sliding scale protocol that indicates the number of units administered based on the blood sugar reading.[11],[12]

There are rapid-, short-, intermediate-, and long-acting insulins. For each type of insulin, it is important to know the onset, peak, and duration of the insulin so that it can be timed appropriately with the patient’s food intake. It is essential to time the administration of insulin with food intake to avoid hypoglycemia. When administering insulin before a meal, always ensure the patient is not nauseated and is able to eat. Short- or rapid-acting insulin may be administered up to 15-30 minutes before meals. Intermediate insulin is typically administered twice daily, at breakfast and dinner, and long-acting insulin is typically administered in the evening.[13],[14]

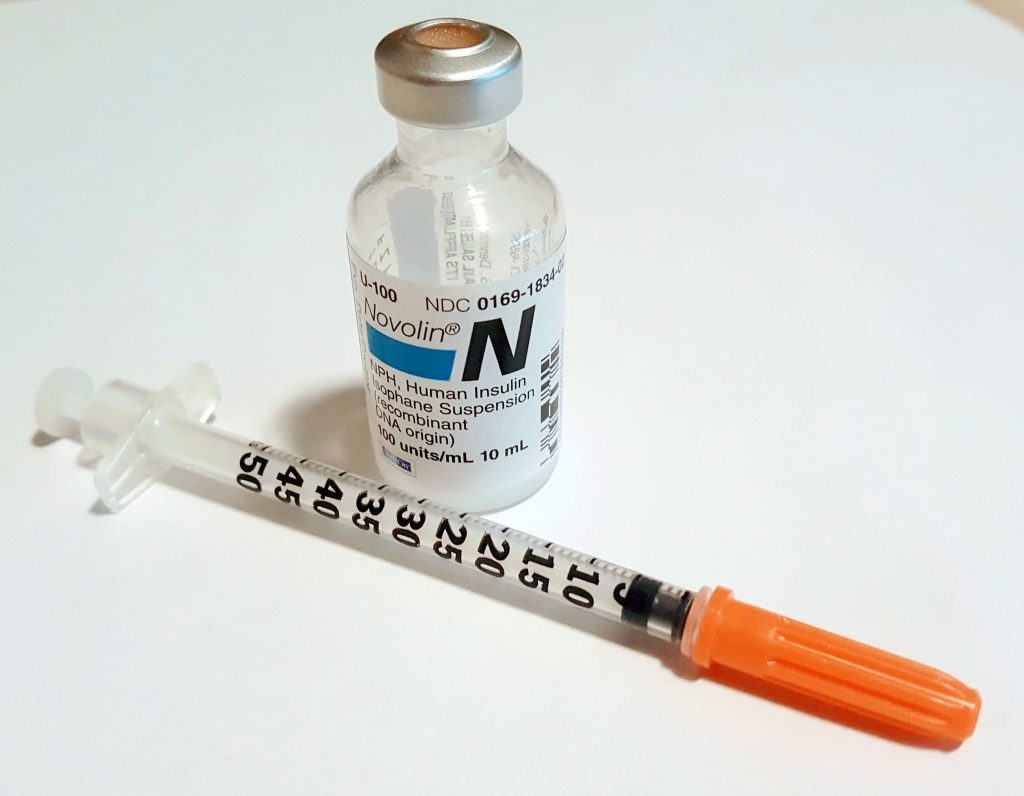

When administering cloudy insulin preparations such as NPH insulin (Humulin-N), gently roll the vial between the palms of your hands to resuspend the medication before withdrawing it from the vial.[15],[16] See Figure 18.25[17] for an image of insulin NPH that is cloudy in color.

Preparing Insulin in a Syringe

When withdrawing insulin from a vial, check the insulin vial to make sure it is the right kind of insulin and that there are no clumps or particles in it. Also, make sure the insulin is not past its expiration date. Pull air into the syringe to match the amount of insulin you plan to remove. Hold the syringe like a pencil and insert the needle into the rubber stopper on the top of the vial. Push the plunger down until all of the air is in the bottle. This helps to keep the right amount of pressure in the bottle and makes it easier to draw up the insulin. With the needle still in the vial, turn the bottle and syringe upside down (vial above syringe). Pull the plunger to fill the syringe to the desired amount. Check the syringe for air bubbles. If you see any large bubbles, push the plunger until the air is purged out of the syringe. Pull the plunger back down to the desired dose. Remove the needle from the bottle. Be careful to not let the needle touch anything until you are ready to inject.[18]

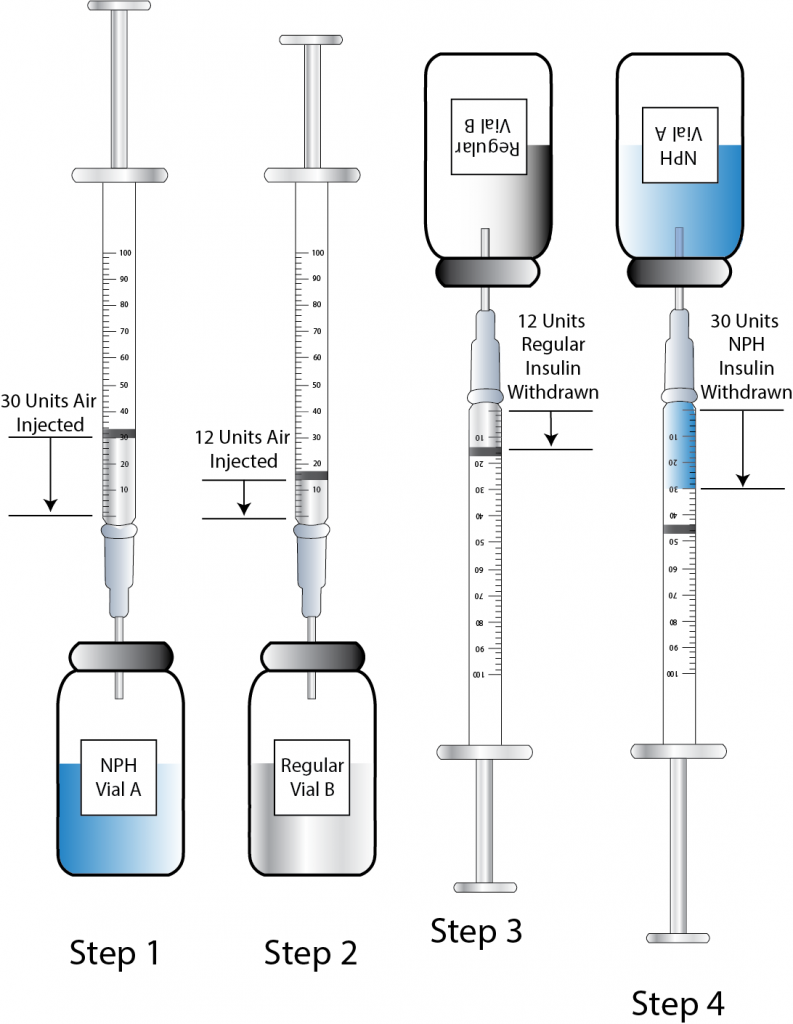

Mixing Two Types of Insulin

If a patient is ordered two types of insulin, some insulins may be mixed together in one syringe. For example, insulin NPH (Novolin-N) can be mixed with insulin regular (Humulin-R), insulin aspart (Novolog), or insulin lispro (Humalog). However, some types of insulin cannot be mixed with other insulin, such as insulin glargine (Lantus) or insulin detemir (Levemir).[19],[20]

When mixing insulin, gather your insulin supplies. Check the insulin vials to make sure they are the right kinds of insulin, there are no clumps or particles in them, and the expiration dates have not passed. Gently mix intermediate or premixed insulin by turning the vial on its side and rolling it between the palms of your hands. Prepare the insulin vials by injecting air into the intermediate insulin vial. Remove the cap from the needle. With the vial of insulin below the syringe, inject an amount of air equal to the dose of intermediate insulin that you will be taking. Do not draw out the insulin into the syringe yet. Remove the needle from the vial. Inject air into the rapid-acting insulin vial equal to the rapid-acting insulin dose. With the needle still in the vial, turn the vial upside down (vial above the syringe) and pull the plunger to fill the syringe with the desired dose. Check the syringe for air bubbles. If you see any large bubbles, push the plunger until the air is purged out of the syringe. Pull the plunger back down to the desired dose. Remove the needle from the vial and recheck your dose. Insert the needle into the vial of cloudy insulin. Turn the vial upside down (vial above syringe) and pull the plunger to draw the dose of intermediate-acting insulin. Because the short-acting insulin is already in the syringe, pull the plunger to the total number of units you need. Do not inject any of the insulin back into the vial because the syringe now contains a mixture of intermediate- and rapid-acting insulin. Remove the needle from the vial and be careful to not let the needle touch anything until you are ready to inject.[21]

When mixing insulin, it is important to always draw up the short-acting insulin first to prevent it from being contaminated with the long-acting insulin. See Figure 18.26[22] for an illustration of the order to follow when mixing insulin.

One anatomic region should be selected for a patient’s insulin injections to maintain consistent absorption, and then sites should be rotated within that region. The abdomen absorbs insulin the fastest, followed by the arms, thighs, and buttocks. It is no longer necessary to rotate anatomic regions, as was once done, because newer insulins have a lower risk for causing hypertrophy of the skin.[23],[24]

Video Review of Mixing Insulin:[25]

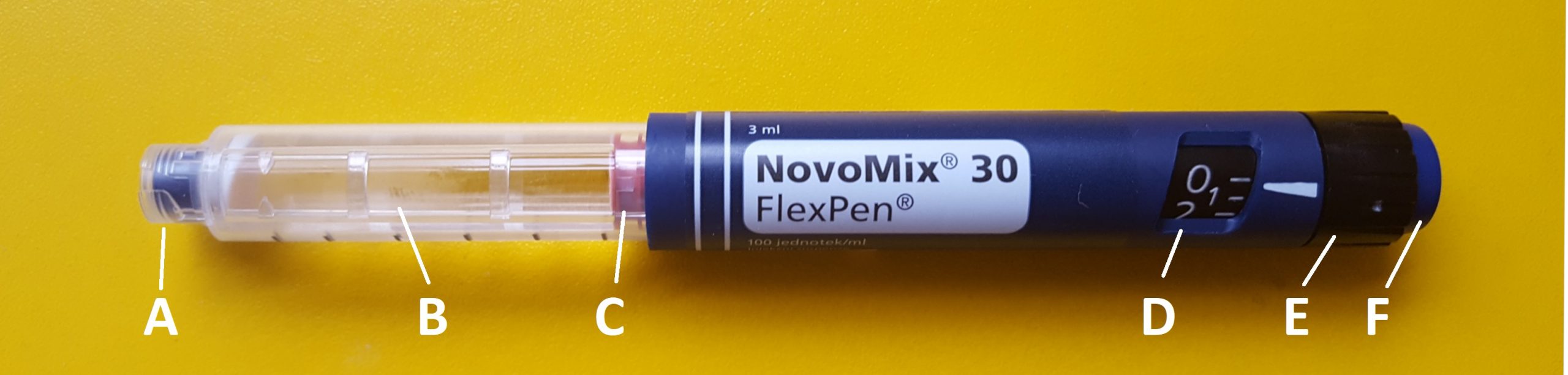

Insulin Pens

Insulin pens are a newer technology designed to be used multiple times for a single person, using a new needle for each injection. See Figure 18.27[26] for an image of an insulin pen. Insulin pens must never be used for more than one person. Regurgitation of blood into the insulin cartridge can occur after injection, creating a risk of blood-borne pathogen transmission if the pen is used for more than one person, even when the needle is changed.[27] Prefilled insulin pens consist of a prefilled cartridge of insulin to which a special, single-use needle is attached. When using an insulin pen for subcutaneous insulin administration, a few additional steps must be taken according to manufacturer guidelines. The needle should be primed with two units of insulin, and then the dosage should be dialed in the dose window. The pen should be held with the hand using four fingers so that the thumb can be used to fully depress the plunger button. The pen should be left in place for ten seconds after the insulin is injected to aid in absorption.[28]

Insulin pens are often prescribed for home use because of their ease of use. Patients and family members must be educated on how to correctly use an insulin pen before discharge. To evaluate a patient’s knowledge of how to correctly administer insulin, ask them to “return demonstrate” the procedure to you.[29],[30]

Special Considerations for Insulin

- Insulin vials are stored in the refrigerator until they are opened. When removed, it should be labelled with an open date and expiration date according to agency policy. When a vial is in use, it should be at room temperature. Do not inject cold insulin because this can cause discomfort.

- Patients who take insulin should monitor their blood sugar (glucose) levels as prescribed by their health care provider.

- Vials of insulin should be inspected prior to use. Any change in appearance may indicate a change in potency. Check the expiration date and do not use it if it has expired.

- All health care workers should be aware of the signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia. Signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia include fruity breath, restlessness, agitation, confusion, slurring of words, clammy skin, inability to concentrate or follow commands, hunger, and nausea. Follow agency policy regarding hypoglycemic reactions.[31]

Insulin Injection Know-HowFor additional details about different types of insulin, hypoglycemia, and safety considerations when administering insulin, visit the "Antidiabetics" section of the "Endocrine" chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

Video Review of Mixing Insulin[32]

Heparin Injections

Heparin is an anticoagulant medication used to treat or prevent blood clots. It comes in various strengths and can be administered subcutaneously or intravenously. Heparin is also considered a high-alert medication because of the potential life-threatening harm that can result from a medication error. See Figure 18.28[33] for an image of a prefilled syringe of enoxaparin (Lovenox), a low-molecular weight heparin, that is typically dispensed in prefilled syringes. Review specific guidelines regarding heparin administration in Table 18.5.[34]

Table 18.5 Specific Guidelines for Administering Heparin[35]

| Guidelines | Additional Information |

|---|---|

| Remember that heparin is considered a high-alert medication. | Heparin is available in vials and prefilled syringes in a variety of concentrations. Because of the dangerous adverse effects of the medication, it is considered a high-alert medication. Always follow agency policy regarding the preparation and administration of heparin. |

| Rotate heparin injection sites. | It is important to rotate heparin sites to avoid bruising in one location. Heparin is absorbed best in the abdominal area, at least 2 inches (5 cm.) away from the umbilicus. |

| Know the risks associated with heparin. | There are many risks associated with the administration of heparin, including bleeding, hematuria, hematemesis, bleeding gums, and melena. Monitor, document, and report these side effects when a patient is receiving heparin. |

| Review lab values. | Review lab values (PTT and aPTT) before and after heparin administration. If injecting low-molecular weight heparin (enoxaparin), review platelet count because heparin can cause thrombocytopenia. |

| Follow administration standards for prepackaged heparin and enoxaparin syringes. | Many agencies use prepackaged heparin and enoxaparin syringes. Always follow the standards for safe medication administration when using prefilled syringes. |

| Assess patient conditions prior to administration. | Some medical conditions increase the patient’s risk for hemorrhage (severe bleeding), such as recent childbirth, severe kidney and liver disease, cerebral or aortic aneurysm, and cerebral vascular accidents (CVA). |

| Assess other medications and diet. | Over-the-counter (OTC) herbal medications, such as garlic, ginger, and horse chestnut, may interact with heparin. Additional medications that may interact or cause increased risk of bleeding include aspirin, NSAIDs, cephalosporins, antithyroid agents, thrombolytics, and probenecids. Foods like green leafy vegetables can alter the therapeutic effect of heparin. |

Device Technology

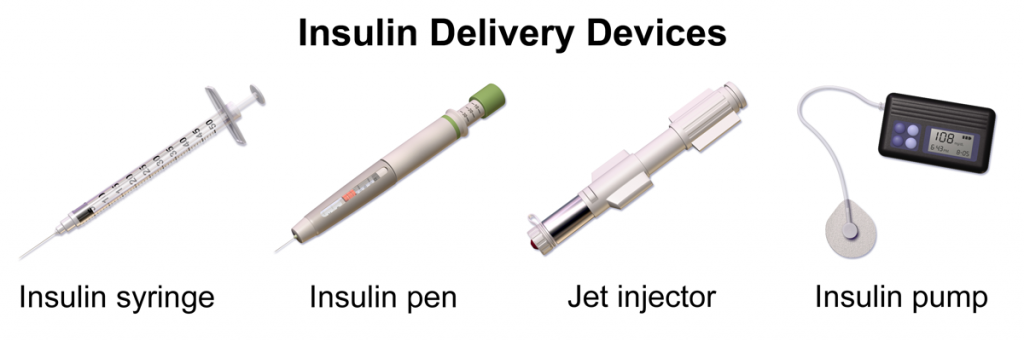

A jet injector is a medical device used for vaccinations and other subcutaneous injections that uses a high-pressure, narrow stream of fluid to penetrate the skin instead of a hypodermic needle. An example of a flu vaccine approved for administration to adults aged 18-64 is AFLURIA © Quadrivalent. The most common injection-site adverse reactions of the jet injector flu vaccine up to seven days post-vaccination were tenderness, swelling, pain, redness, itching, and bruising.[36] Insulin can also be successfully administered via a jet injector, with research demonstrating improved glucose control because the insulin is spread out over a larger area of tissue and enters the bloodstream faster than when administered by an insulin pen or needle. Patients have indicated preference for insulin delivered by the jet injector compared to the insulin pen or syringe because it is needle-free with less tissue injury and pain as compared to the needle injection.[37] See Figure 18.29[38] for an image comparing insulin delivery devices.

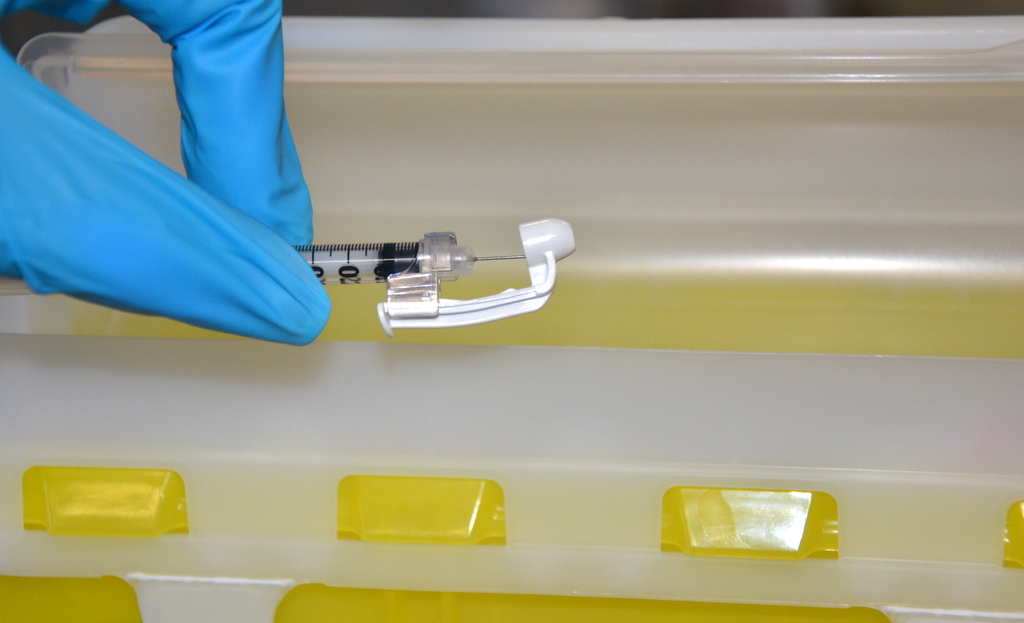

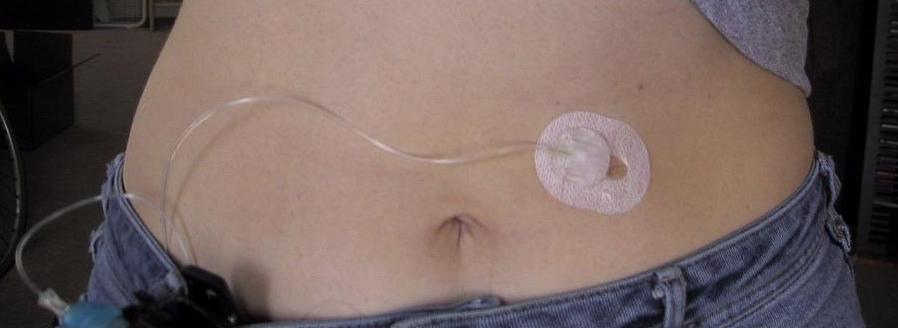

Another type of new technology used to continuously deliver subcutaneous insulin is the insulin pump. Pumps are a computerized device attached to the body, either with tubing or attached to the skin. They are programmed to release small doses of insulin (continuously or as a surge bolus dose) close to mealtime to control the rise in blood sugar after a meal. They work by closely mimicking the body's normal release of insulin. Insulin doses are delivered through a flexible plastic tube called a catheter. With the aid of a small needle, the catheter is inserted through the skin into the fatty tissue and is taped in place.[39] See Figure 18.30[40] for an image of an insulin pump infusion set attached to a patient.

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

Mr. Jones is a 76-year-old patient admitted to the medical surgical floor with complications of a nonhealing foot ulcer. Mr. Jones has a history of diabetes, hypertension, and COPD. He has a BMI of 29. His daily medications include metformin, Lisinopril, and prednisone. His wife has recently passed away and he lives alone.

- Based upon what is known about Mr. Jones, what factors might be contributing to his nonhealing wound?

- What other factors that influence wound healing might be important to assess with Mr. Jones?

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of “Rectal Medication Administration” using a rectal suppository.[41]

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

Follow Steps 1 through 12 in the "Checklist for Oral Medication Administration."

- If possible, have the patient defecate prior to rectal medication administration.

- Ensure that you have water-soluble lubricant available for medication administration.

- Explain the procedure to the patient. If a patient prefers to self-administer the suppository/enema, give specific instructions to the patient on correct procedure.

- Raise the bed to working height:

- Position the patient on left side with the upper leg flexed over the lower leg toward the waist (Sims position).

- Provide privacy and drape the patient with only the buttocks and anal area exposed.

- Place a drape underneath the patient’s buttocks.

- Apply clean, nonsterile gloves.

- Assess the patient for diarrhea or active rectal bleeding.

- Remove the wrapper from the suppository/tip of enema and lubricate the rounded tip of the suppository and index finger of the dominant hand with lubricant. If administering an enema, lubricate the tip of the enema.

- Separate the buttocks with the nondominant hand and, using the gloved index finger of dominant hand, insert the suppository (rounded tip toward patient) into the rectum toward the umbilicus while having the patient take a deep breath, exhale through the mouth, and relax the anal sphincter. Insert the suppository against the rectal mucosa for optimal absorption, about 3 to 4 inches for an adult and 1 to 2 inches for a child. Do not insert the suppository into feces. If administering an enema, expel the air from the enema and then insert the tip of the enema into the rectum toward the umbilicus while having the patient take a deep breath, exhale through the mouth, and relax the anal sphincter. Roll the plastic bottle from bottom to tip until all solution has entered the rectum and colon. Remove the bottle.

- Monitor the patient for signs of dizziness. Unintended vagal stimulation may occur, resulting in bradycardia in some patients. Be aware that the rectal route may not be suitable for certain cardiac conditions.

- When administering a suppository, ask the patient to remain on side for 5 to 10 minutes.

- When administering an enema, ask the patient to retain the enema until the urge to defecate is strong, usually about 5 to 15 minutes.

- Discard gloves by turning them inside out before disposing them. Discard used supplies as per agency policy and perform hand hygiene.

- Assist the patient to a comfortable position, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Document medication administration and the related assessment findings. Report any unexpected findings according to agency policy.

- Evaluate the patient's response to the medication within the appropriate time frame.

Military time is a method of measuring the time based on the full 24 hours of the day rather than two groups of 12 hours indicated by AM and PM. It is also referred to as using a 24-hour clock. Using military time is the standard method used to indicate time for medication administration. The use of military time reduces potential confusion that may be caused by using AM and PM and also avoids potential duplication when giving scheduled medications. For example, instead of stating medication is due at 7 AM and 7 PM, it is documented on the medication administration record (MAR) as due at 0700 and 1900. See Figure 5.5[42] for an example clock and Table 5.3 for a military time conversion chart.

- Conversion of an AM time to military time simply involves removing the colon and adding a zero to the time. For example, 6:30 AM becomes 0630.

- Conversion of a PM time to military time involves removing the colon and adding 1200 to the time. For example, 7:15 PM becomes 1915.

Table 5.3 Military Time Conversion Chart

| Normal Time | Military Time | Normal Time | Military Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12:00 AM | 0000 | 12:00 PM | 1200 |

| 1:00 AM | 0100 | 1:00 PM | 1300 |

| 2:00 AM | 0200 | 2:00 PM | 1400 |

| 3:00 AM | 0300 | 3:00 PM | 1500 |

| 4:00 AM | 0400 | 4:00 PM | 1600 |

| 5:00 AM | 0500 | 5:00 PM | 1700 |

| 6:00 AM | 0600 | 6:00 PM | 1800 |

| 7:00 AM | 0700 | 7:00 PM | 1900 |

| 8:00 AM | 0800 | 8:00 PM | 2000 |

| 9:00 AM | 0900 | 9:00 PM | 2100 |

| 10:00 AM | 1000 | 10:00 PM | 2200 |

| 11:00 AM | 1100 | 11:00 PM | 2300 |

Practice Problems: Military Time

Practice converting military time using the following problems. The answers are found in the Answer Key (Math Calculations Chapter section) at the end of the book.

- A patient has a medication scheduled for 1930. What time does this indicate? Include AM or PM.

- As you prepare to administer a PRN dose of pain medication, you notice the previous dose was administered at 0030. What time does this indicate? Include AM or PM.

- You administer medication to a patient at 9 AM. How should this be documented in military time?

- You administer medication to a patent at 10 PM. How should this be documented in military time?

Before discussing specific procedures related to facilitating bowel and bladder function, let’s review basic concepts related to urinary and bowel elimination. When facilitating alternative methods of elimination, it is important to understand the anatomy and physiology of the gastrointestinal and urinary systems, as well as the adverse effects of various conditions and medications on elimination. Use the hyperlinks below to review information about these topics.

For more information about the anatomy and physiology of the gastrointestinal system and medications used to treat diarrhea and constipation, visit the "Gastrointestinal" chapter of the Open RN Nursing Pharmacology textbook.

For more information about the anatomy and physiology of the kidneys and diuretic medications used to treat fluid overload, visit the "Cardiovascular and Renal System" chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology textbook.

For more information about applying the nursing process to facilitate elimination, visit the "Elimination" chapter in Open RN Nursing Fundamentals.

Urinary Elimination Devices

This section will focus on the devices used to facilitate urinary elimination. Urinary catheterization is the insertion of a catheter tube into the urethral opening and placing it in the neck of the urinary bladder to drain urine. There are several types of urinary elimination devices, such as indwelling catheters, intermittent catheters, suprapubic catheters, and external devices. Each of these types of devices is described in the following subsections.

Indwelling Catheter

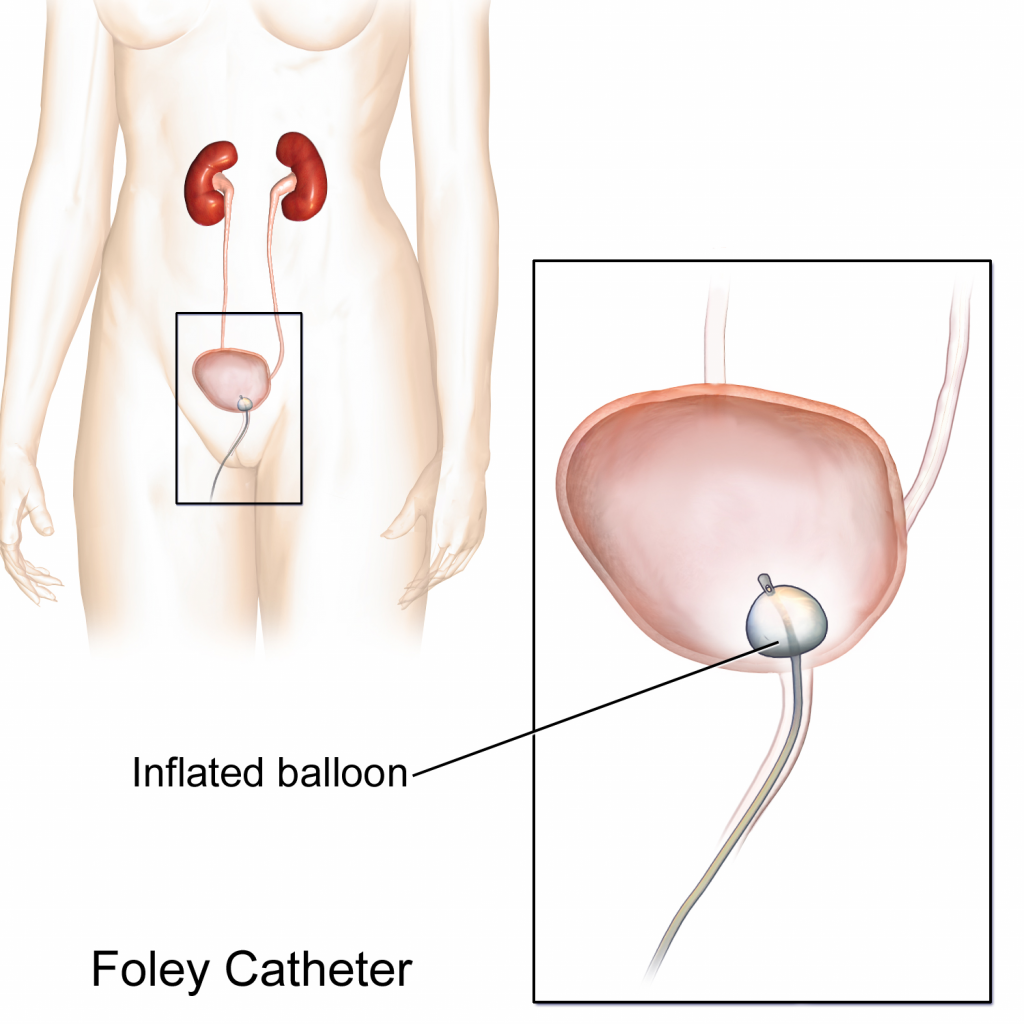

An indwelling catheter, often referred to as a “Foley catheter,” refers to a urinary catheter that remains in place after insertion into the bladder for the continual collection of urine. It has a balloon on the insertion tip to maintain placement in the neck of the bladder. The other end of the catheter is attached to a drainage bag for the collection of urine. See Figure 21.1[43] for an illustration of the anatomical placement of an indwelling catheter in the bladder neck.

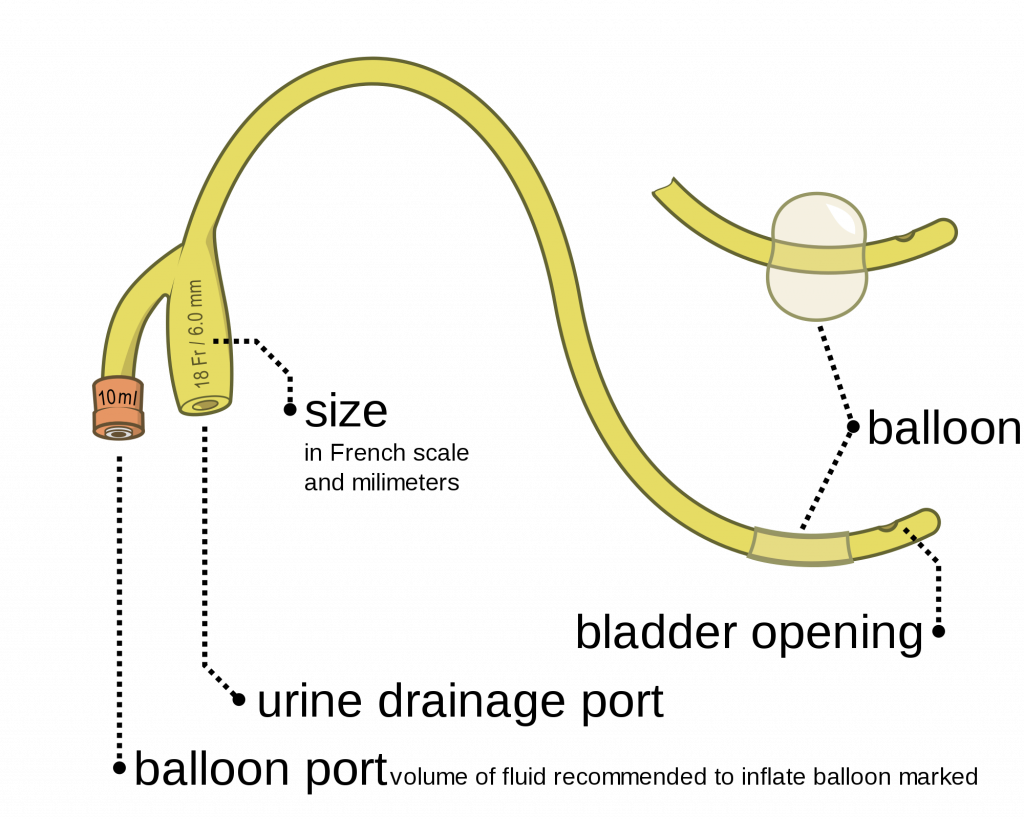

The distal end of an indwelling catheter has a urine drainage port that is connected to a drainage bag. The size of the catheter is marked at this end using the French catheter scale. A balloon port is also located at this end, where a syringe is inserted to inflate the balloon after it is inserted into the bladder. The balloon port is marked with the amount of fluid required to fill the balloon. See Figure 21.2[44] for an image of the parts of an indwelling catheter.

Catheters have different sizes, with the larger the number indicating a larger diameter of the catheter. See Figure 21.3[45] for an image of the French Catheter Scale.

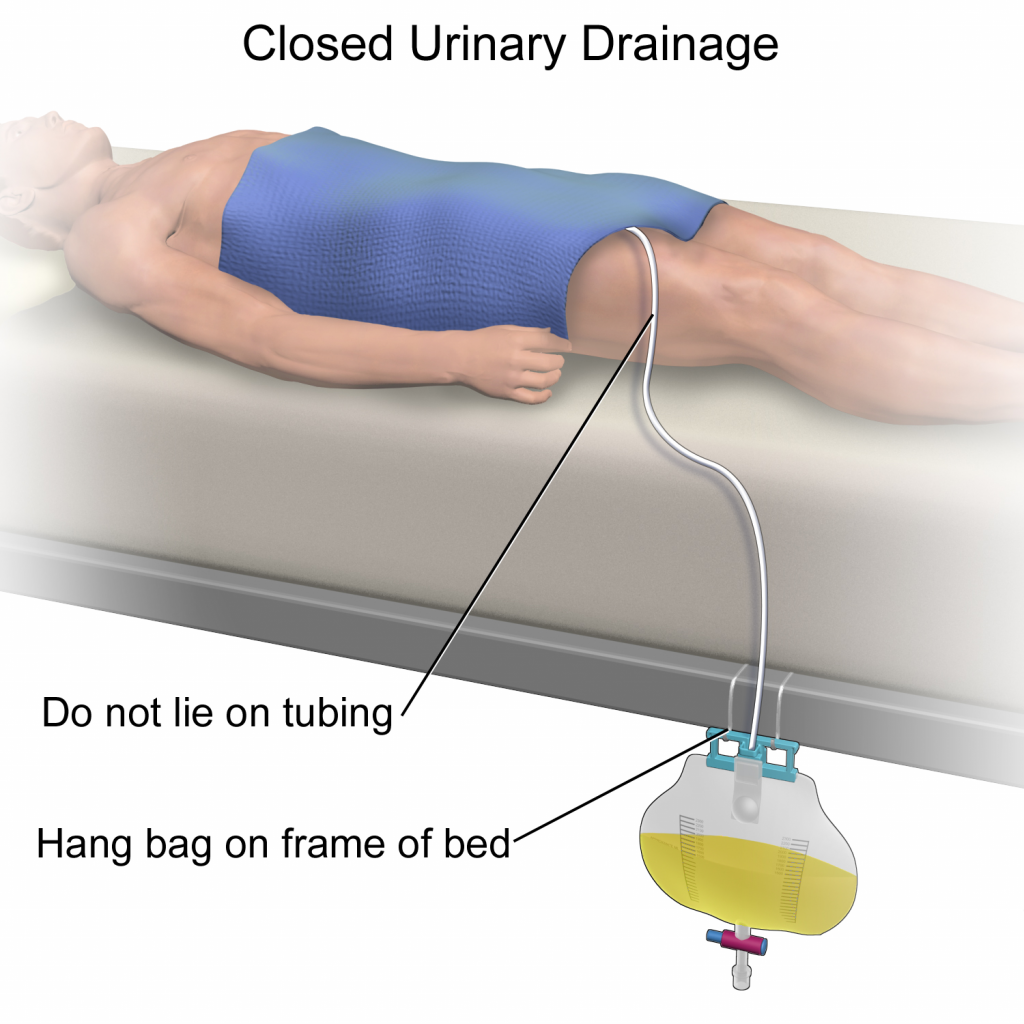

There are two common types of bags that may be attached to an indwelling catheter. During inpatient or long-term care, larger collection bags that can hold up to 2 liters of fluid are used. See Figure 21.4[46] for an image of a typical collection bag attached to an indwelling catheter. These bags should be emptied when they are half to two-thirds full to prevent traction on the urethra from the bag. Additionally, the collection bag should always be placed below the level of the patient’s bladder so that urine flows out of the bladder and urine does not inadvertently flow back into the bladder. Ensure the tubing is not coiled, kinked, or compressed so that urine can flow unobstructed into the bag. Slack should be maintained in the tubing to prevent injury to the patient's urethra. To prevent the development of a urinary tract infection, the bag should not be permitted to touch the floor.

See Figure 21.5[47] for an illustration of the placement of the urine collection bag when the patient is lying in bed.

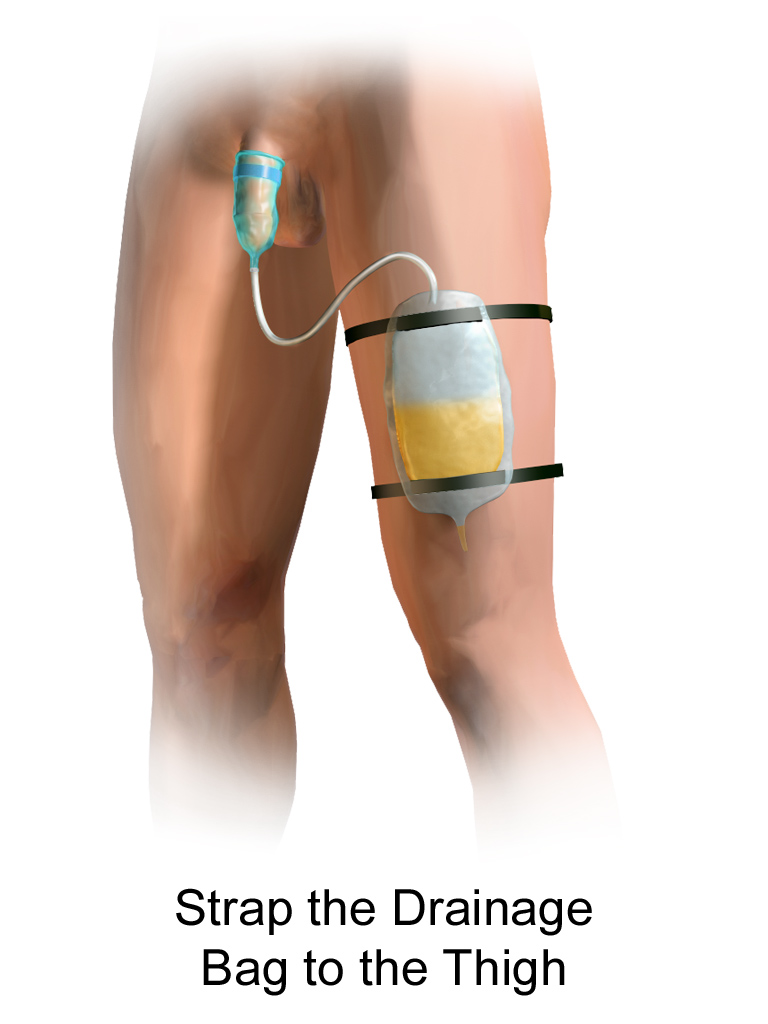

A second type of urine collection bag is a leg bag. Leg bags provide discretion when the patient is in public because they can be worn under clothing. However, leg bags are small and must be emptied more frequently than those used during inpatient care. Figure 21.6[48] for an image of leg bag and Figure 21.7[49] for an illustration of an indwelling catheter attached to a leg bag.

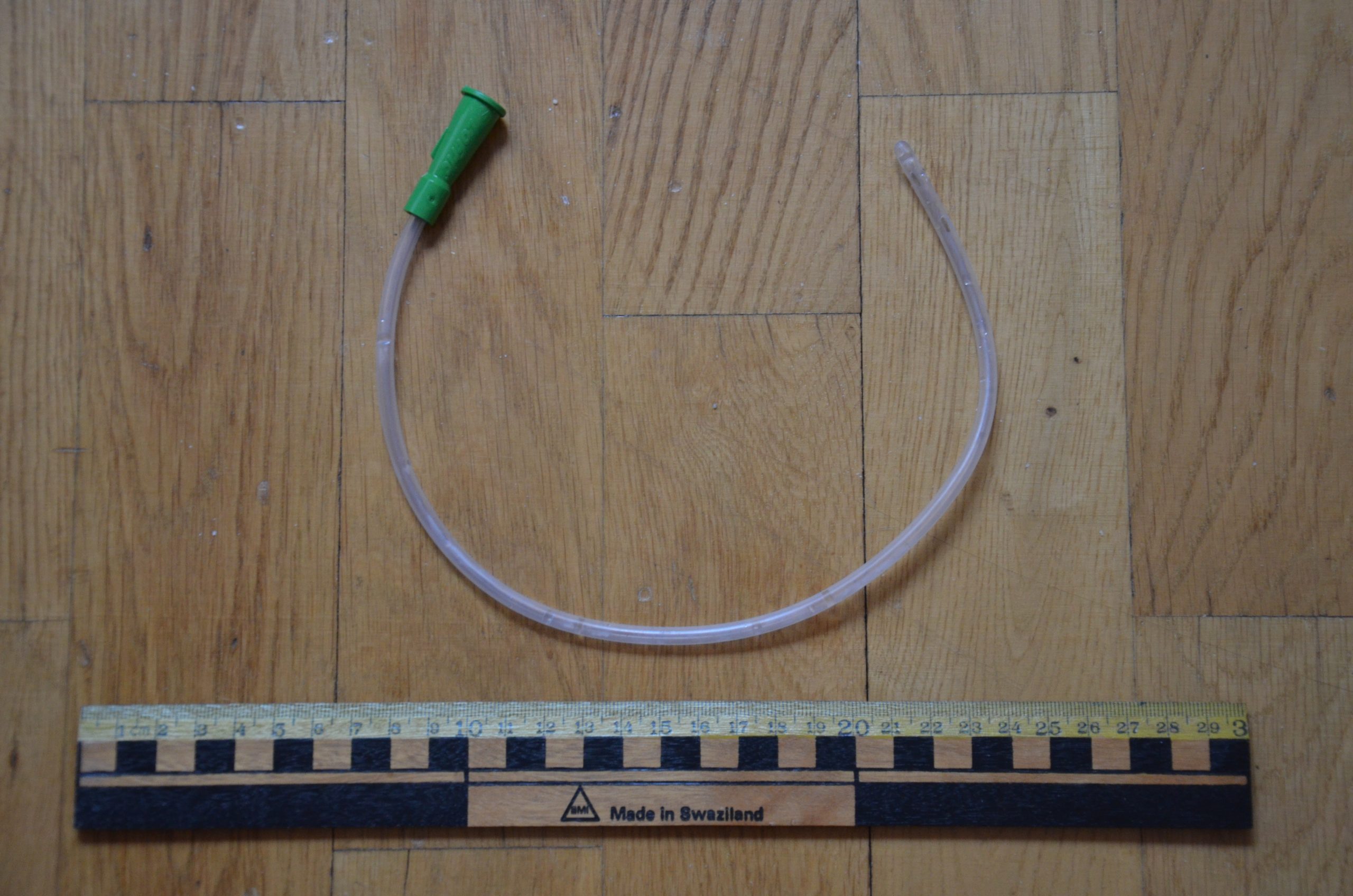

Straight Catheter

A straight catheter is used for intermittent urinary catheterization. The catheter is inserted to allow for the flow of urine and then immediately removed, so a balloon is not required at the insertion tip. See Figure 21.8[50] for an image of a straight catheter. Intermittent catheterization is used for the relief of urinary retention. It may be performed once, such as after surgery when a patient is experiencing urinary retention due to the effects of anesthesia, or performed several times a day to manage chronic urinary retention. Some patients may also independently perform self-catheterization at home to manage chronic urinary retention caused by various medical conditions. In some situations, a straight catheter is also used to obtain a sterile urine specimen for culture when a patient is unable to void into a sterile specimen cup. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), intermittent catheterization is preferred to indwelling urethral catheters whenever feasible because of decreased risk of developing a urinary tract infection.[51]

Other Types of Urinary Catheters

Coude Catheter Tip

Coude catheter tips are curved to follow the natural curve of the urethra during catheterization. They are often used when catheterizing male patients with enlarged prostate glands. See Figure 21.9[52] for an example of a urinary catheter with a coude tip. During insertion, the tip of the Coude catheter must be pointed anteriorly or it can cause damage the urethra. A thin line embedded in the catheter provides information regarding orientation during the procedure; maintain the line upwards to keep it pointed anteriorly.

Irrigation Catheter

Irrigation catheters are typically used after prostate surgery to flush the surgical area. These catheters are larger in size to allow for larger amounts of fluid to flush. See Figure 21.10[53] for an image comparing a larger 20 French catheter (typically used for irrigation) to a 14 French catheter (typically used for indwelling catheters).

Suprapubic Catheters

Suprapubic catheters are surgically inserted through the abdominal wall into the bladder. This type of catheter is typically inserted when there is a blockage within the urethra that does not allow the use of a straight or indwelling catheter. Suprapubic catheters may be used for a short period of time for acute medical conditions or may be used permanently for chronic conditions. See Figure 21.11[54] for an image of a suprapubic catheter. The insertion site of a suprapubic catheter must be cleaned regularly according to agency policy with appropriate steps to prevent skin breakdown.

Male Condom Catheter

A condom catheter is a noninvasive device used for males with incontinence. It is placed over the penis and connected to a drainage bag. This device protects and promotes healing of the skin around the perineal area and inner legs and is used as an alternative to an indwelling urinary catheter. See Figure 21.12[55] for an image of a condom catheter and Figure 21.13[56] for an illustration of a condom catheter attached to a leg bag.

Female External Urinary Catheter

Female external urinary catheters (FEUC) have been recently introduced into practice to reduce the incidence of catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) in women.[57] The external female catheter device is made of a purewick material that is placed externally over the female’s urinary meatus. The wicking material is attached to a tube that is hooked to a low-suction device. When the wick becomes saturated with urine, it is suctioned into a drainage canister. Preliminary studies have found that utilizing the FEUC device reduced the risk for CAUTI.[58],[59]

View these supplementary videos on female external urinary catheters:

Students demonstrate use of Purewick Female External Catheter[60]

How to use the use the PureWick - a female external catheter[61]

A catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) is a common, life-threatening complication caused by indwelling urinary catheters. The development of a CAUTI is associated with patients’ increased length of stay in the hospital, resulting in additional hospital costs and a higher risk of death. It is estimated that 17% to 69% of CAUTI cases are preventable, meaning that up to 380,000 infections and 9,000 patient deaths per year related to CAUTI can be prevented with appropriate nursing measures.[62]

Nurses can save lives, prevent harm, and lower health care costs by following interventions outlined in the document created by the American Nurses Association titled Streamlined Evidence-Based RN Tool: Catheter Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI) Prevention. Review the entire tool in the hyperlink provided below. Key interventions include the following:

- Ensure the patient meets CDC-approved indications prior to inserting an indwelling catheter. If the patient does not meet the approved indications, contact the provider and advocate for an alternative method to facilitate elimination.

- According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), appropriate indications for inserting an indwelling urinary catheter include the following[63]:

- Urinary retention or bladder outlet obstruction

- Hourly monitoring of urinary output in critically ill patients

- Perioperative use for selected surgeries

- Healing of open sacral and perineal wounds in patients with urinary incontinence

- Prolonged immobilization

- End-of-life care[64]

- Inappropriate reasons for inserting an indwelling urinary catheter include the following:

- Substitution of nursing care for a patient or resident with incontinence

- A means for obtaining a urine culture when a patient can voluntarily void

- Prolonged postoperative care without appropriate indications[65]

- According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), appropriate indications for inserting an indwelling urinary catheter include the following[63]:

- After an indwelling urinary catheter is inserted, assess the patient daily to determine if the patient still meets the CDC criteria for an indwelling catheter and document the findings. If the patient no longer meets the approved criteria, follow agency policy for removal.

- When an indwelling catheter is in place, prevent CAUTI by following the maintenance steps outlined by the CDC.

- Continually monitor for signs of a CAUTI and report concerns to the health care provider.[66]

- Signs and symptoms of CAUTI to urgently report to the health care provider include fever greater than 38 degrees Celsius, change in mental status such as confusion or lethargy, chills, malodorous urine, and suprapubic or flank pain. Flank pain can be assessed by assisting the patient to a sitting or side-lying position and percussing the costovertebral areas.[67]

Streamlined Evidence-Based RN Tool: Catheter Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI) Prevention