14.3 Common Integumentary Conditions

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

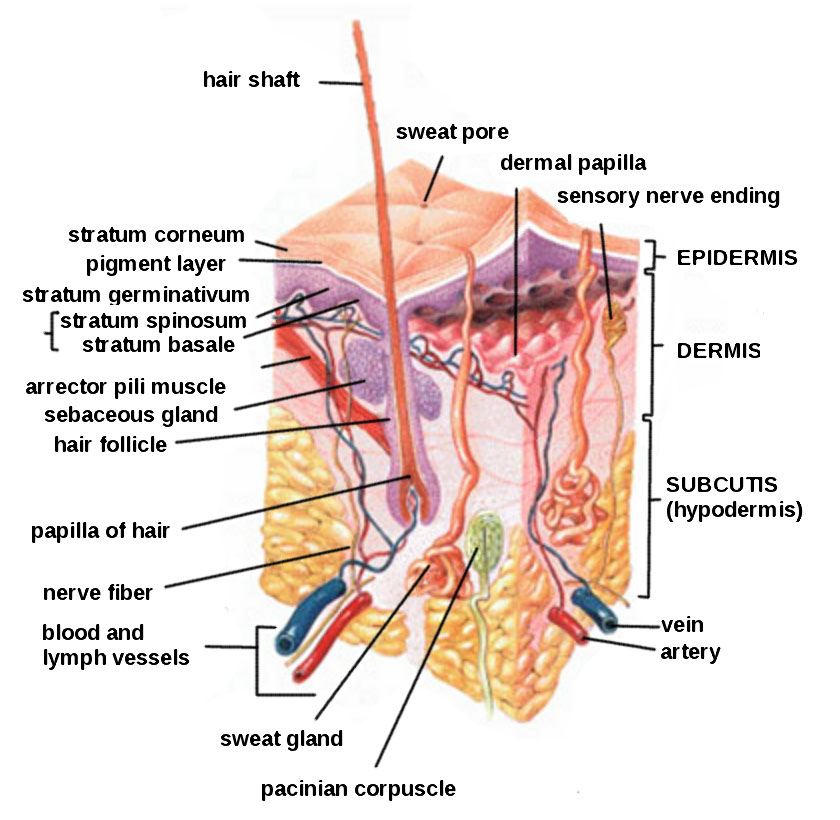

Now that we have reviewed the anatomy of the integumentary system, let’s review common conditions that you may find during a routine integumentary assessment.

Acne

Acne is a skin disturbance that typically occurs on areas of the skin that are rich in sebaceous glands, such as the face and back. It is most common during puberty due to associated hormonal changes that stimulate the release of sebum. An overproduction and accumulation of sebum, along with keratin, can block hair follicles. Acne results from infection by acne-causing bacteria and can lead to potential scarring.[1] See Figure 14.8[2] for an image of acne.

Lice and Nits

Head lice are tiny insects that live on a person’s head. Adult lice are about the size of a sesame seed, but the eggs, called nits, are smaller and can appear like a dandruff flake. See Figure 14.9[3] for an image of very small white nits in a person’s hair. Children ages 3-11 often get head lice at school and day care because they have head-to-head contact while playing together. Lice move by crawling and spread by close person-to-person contact. Rarely, they can spread by sharing personal belongings such as hats or hair brushes. Contrary to popular belief, personal hygiene and cleanliness have nothing to do with getting head lice. Symptoms of head lice include the following:

- Tickling feeling in the hair

- Frequent itching, which is caused by an allergic reaction to the bites

- Sores from scratching, which can become infected with bacteria

- Trouble sleeping due to head lice being most active in the dark

A diagnosis of head lice usually comes from observing a louse or nit on a person’s head. Because they are very small and move quickly, a magnifying lens and a fine-toothed comb may be needed to find lice or nits. Treatments for head lice include over-the-counter and prescription shampoos, creams, and lotions such as permethrin lotion.[4]

Burns

A burn results when the skin is damaged by intense heat, radiation, electricity, or chemicals. The damage results in the death of skin cells, which can lead to a massive loss of fluid due to loss of the skin’s protection. Burned skin is also extremely susceptible to infection due to the loss of protection by intact layers of skin.

Burns are classified by the degree of their severity. A first-degree burn, also referred to as a superficial burn, only affects the epidermis. Although the skin may be painful and swollen, these burns typically heal on their own within a few days. Mild sunburn fits into the category of a first-degree burn. A second-degree burn, also referred to as a partial thickness burn, affects both the epidermis and a portion of the dermis. These burns result in swelling and a painful blistering of the skin. It is important to keep the burn site clean to prevent infection. With good care, a second degree burn will heal within several weeks. A third-degree burn, also referred to as a full thickness burn, extends fully into the epidermis and dermis, destroying the tissue and affecting the nerve endings and sensory function. These are serious burns that require immediate medical attention. A fourth-degree burn, also referred to as a deep full thickness burn, is even more severe, affecting the underlying muscle and bone. Third- and fourth-degree burns are usually not as painful as second degree burns because the nerve endings are damaged. Full thickness burns require debridement (removal of dead skin) followed by grafting of the skin from an unaffected part of the body or from skin grown in tissue culture.[5] See Figure 14.10[6] for an image of a patient recovering from a second-degree burn on the hand.

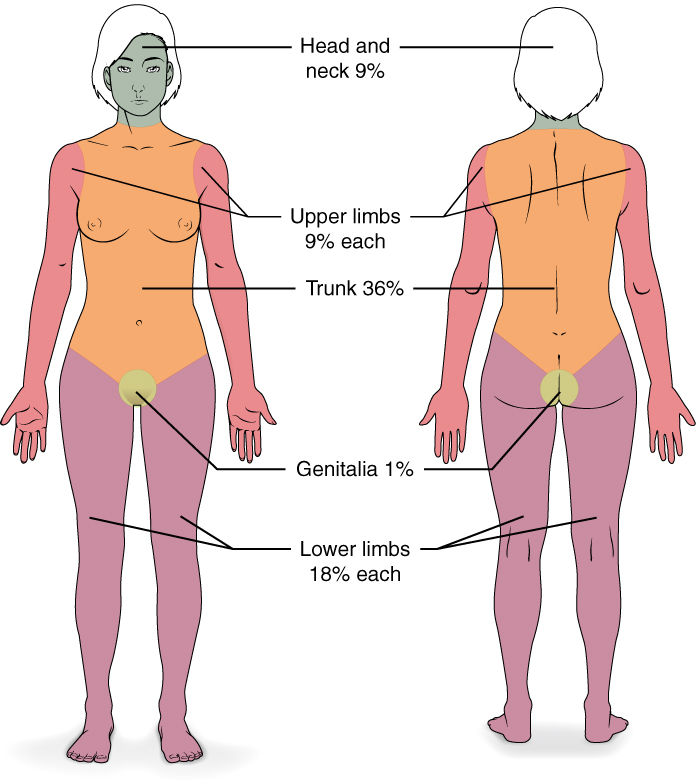

Severe burns are quickly measured in emergency departments using a tool called the “rule of nines,” which associates specific anatomical locations with a percentage that is a factor of nine. Rapid estimate of the burned surface area is used to estimate intravenous fluid replacement because patients will have massive fluid losses due to the removal of the skin barrier.[7] See Figure 14.11[8] for an illustration of the rule of nines. The head is 9% (4.5% on each side), the upper limbs are 9% each (4.5% on each side), the lower limbs are 18% each (9% on each side), and the trunk is 36% (18% on each side).

Scars

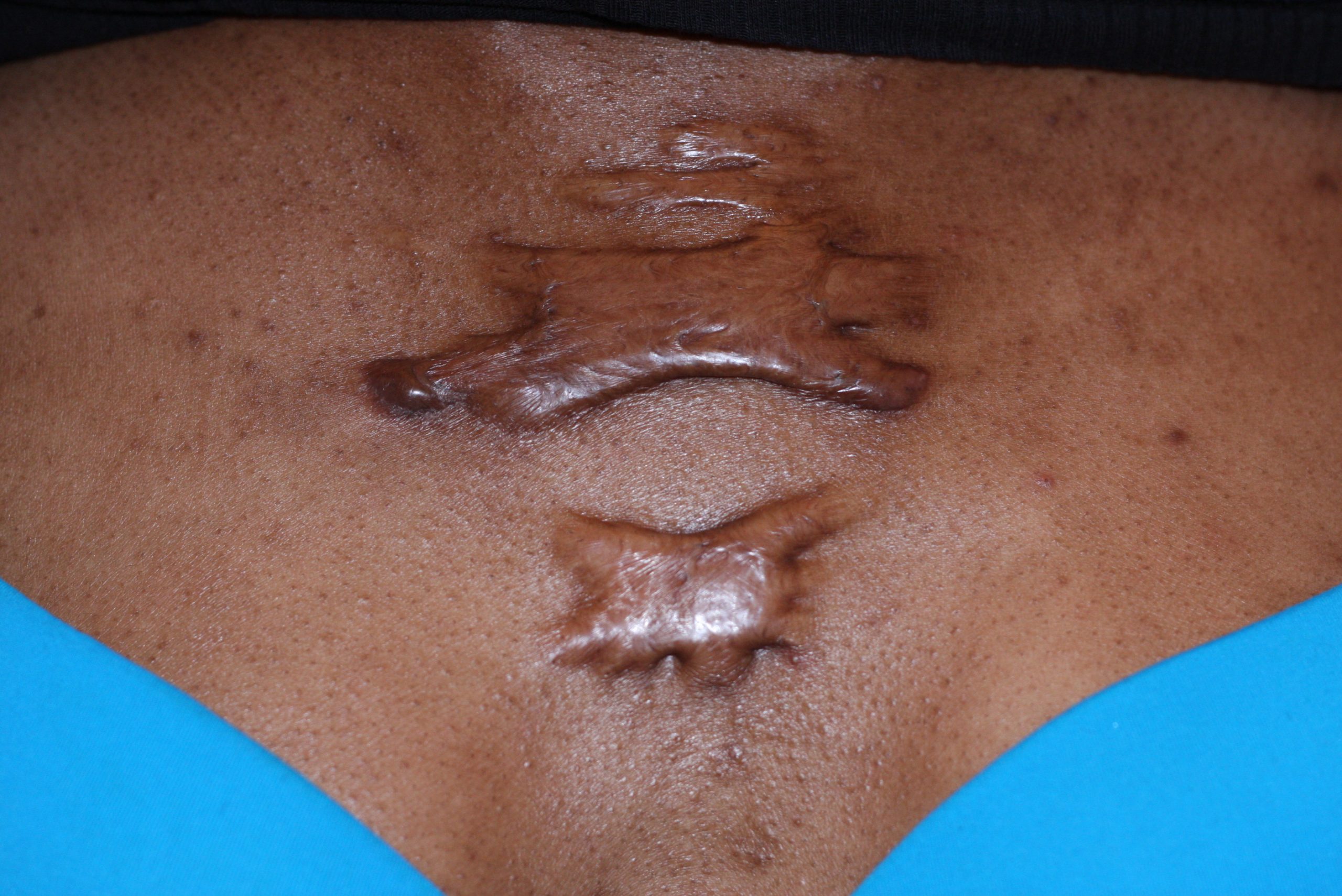

Most cuts and wounds cause scar formation. A scar is collagen-rich skin formed after the process of wound healing. Sometimes there is an overproduction of scar tissue because the process of collagen formation does not stop when the wound is healed, resulting in the formation of a raised scar called a keloid.[9] Keloids are more common in patients with darker skin color. See Figure 14.12[10] for an image of a keloid that has developed from a scar on a patient’s chest wall.

Skin Cancer

Skin cancer is common, with one in five Americans experiencing some type of skin cancer in their lifetime. Basal cell carcinoma is the most common of all cancers that occur in the United States and is frequently found on areas most susceptible to long-term sun exposure such as the head, neck, arms, and back. Basal cell carcinomas start in the epidermis and become an uneven patch, bump, growth, or scar on the skin surface. Treatment options include surgery, freezing (cryosurgery), and topical ointments.[11]

Squamous cell carcinoma presents as lesions commonly found on the scalp, ears, and hands. If not removed, squamous cell carcinomas can metastasize to other parts of the body. Surgery and radiation are used to cure squamous cell carcinoma. See Figure 14.13[12] for an image of squamous cell carcinoma.[13]

Melanoma is a cancer characterized by the uncontrolled growth of melanocytes, the pigment-producing cells in the epidermis. A melanoma commonly develops from an existing mole. See Figure 14.14[14] for an image of a melanoma. Melanoma is the most fatal of all skin cancers because it is highly metastatic and can be difficult to detect before it has spread to other organs. Melanomas usually appear as asymmetrical brown and black patches with uneven borders and a raised surface. Treatment includes surgical excision and immunotherapy.[15]

Fungal (Tinea) Infections

Tinea is the name of a group of skin diseases caused by a fungus. Types of tinea include ringworm, athlete’s foot, and jock itch. These infections are usually not serious, but they can be uncomfortable because of the symptoms of itching and burning. They can be transmitted by touching infected people, damp surfaces such as shower floors, or even from pets.[16] Ringworm (tinea corporis) is a type of rash that forms on the body that typically looks like a red ring with a clear center, although a worm doesn’t cause it. Scalp ringworm (tinea capitals) causes itchy, red patches on the head that can leave bald spots. Athlete’s foot (tinea pedis) causes itching, burning, and cracked skin between the toes. Jock itch (tinea cruris) causes an itchy, burning rash in the groin area. Fungal infections are often treated successfully with over-the-counter creams and powders, but some require prescription medicine such as nystatin. See Figure 14.15[17] for an image of a tinea in a patient’s groin.[18]

Impetigo

Impetigo is a common skin infection caused by bacteria in children between the ages two and six. It is commonly caused by Staphylococcus (staph) or Streptococcus (strep) bacteria. See Figure 14.16[19] for an image of impetigo. Impetigo often starts when bacteria enter a break in the skin, such as a cut, scratch, or insect bite. Symptoms start with red or pimple-like sores surrounded by red skin. The sores fill with pus and then break open after a few days and form a thick crust. They are often itchy, but scratching them can spread the sores. Impetigo can spread by contact with sores or nasal discharge from an infected person and is treated with antibiotics.

Edema

Edema is caused by fluid accumulation within the tissues often caused by underlying cardiovascular or renal disease. Read more about edema in the “Basic Concepts” section of the “Cardiovascular Assessment” chapter.

Lymphedema

Lymphedema is the medical term for a type of swelling that occurs when lymph fluid builds up in the body’s soft tissues due to damage to the lymph system. It often occurs unilaterally in the arms or legs after surgery has been performed that injured the regional lymph nodes. See Figure 14.17[20] for an image of lower extremity edema. Causes of lymphedema include infection, cancer, scar tissue from radiation therapy, surgical removal of lymph nodes, or inherited conditions. There is no cure for lymphedema, but elevation of the affected extremity is vital. Compression devices and massage can help to manage the symptoms. See Figure 14.18[21] for an image of a specialized compression dressing used for lymphedema. It is also important to remember to avoid taking blood pressure on a patient’s extremity with lymphedema.[22]

Jaundice

Jaundice causes skin and sclera (whites of the eyes) to turn yellow. See Figure 14.19[23] for an image of a patient with jaundice visible in the sclera and the skin. Jaundice is caused by too much bilirubin in the body. Bilirubin is a yellow chemical in hemoglobin, the substance that carries oxygen in red blood cells. As red blood cells break down, the old ones are processed by the liver. If the liver can’t keep up due to large amounts of red blood cell breakdown or liver damage, bilirubin builds up and causes the skin and sclera to appear yellow. New onset of jaundice should always be reported to the health care provider.

Many healthy babies experience mild jaundice during the first week of life that usually resolves on its own, but some babies require additional treatment such as light therapy. Jaundice can happen at any age for many reasons, such as liver disease, blood disease, infections, or side effects of some medications.[24]

Pressure Injuries

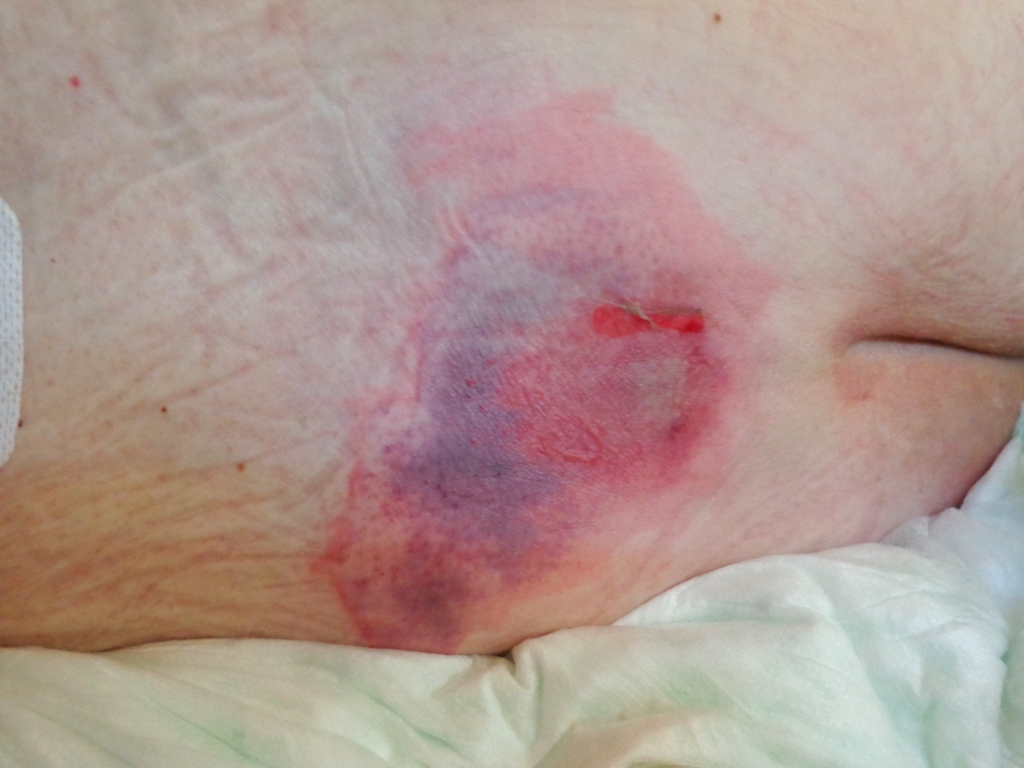

Pressure injuries also called bedsores, form when a patient’s skin and soft tissue press against a hard surface, such as a chair or bed, for a prolonged period of time. The pressure against a hard surface reduces blood supply to that area, causing the skin tissue to become damaged and become an ulcer. Patients are at high risk of developing a pressure injury if they spend a lot of time in one position, have decreased sensation, or have bladder or bowel leakage.[25] See Figure 14.20[26] for an image of a pressure ulcer injury on a bed-bound patient’s back. Read more information about assessing and caring for pressure injury in the “Wound Care” chapter.

Petechiae

Petechiae are tiny red dots caused by bleeding under the skin that may appear like a rash. Large petechiae are called purpura. An easy method used to assess for petechiae is to apply pressure to the rash with a gloved finger. A rash will blanch (i.e., whiten with pressure) but petechiae and purpura do not blanch. See Figure 14.21[27] for an image of petechiae and purpura. New onset of petechiae should be immediately reported to the health care provider because it can indicate a serious underlying medical condition.[28]

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Acne vulgaris on a very oily skin.jpg” by Roshu Bangal is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Fig.5. Louse nites.jpg” by KostaMumcuoglu at English Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2020, Aug 17]. Head lice; [reviewed 2016, Sep 9; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/headlice.html ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “1Veertje hand-burn-do8.jpg” by 1Veertje is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Moore, Waheed, and Burns and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “513 Degree of burns.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Keloid-Butterfly, Chest Wall.JPG” by Htirgan is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Squamous cell carcinoma (3).jpg” by unknown photographer, provided by National Cancer Institute is licensed under CC0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/5-4-diseases-disorders-and-injuries-of-the-integumentary-system ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Melanoma (2).jpg” by unknown photographer, provided by National Cancer Institute is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/5-4-diseases-disorders-and-injuries-of-the-integumentary-system ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2020, Aug 17]. Tinea infections; [reviewed 2016, Apr 4; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/tineainfections.html#:~:text=Tinea%20is%20the%20name%20of,or%20even%20from%20a%20pet ↵

- “Tinea cruris.jpg” by Robertgascoin is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2020, Aug 17]. Tinea infections; [reviewed 2016, Apr 4; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/tineainfections.html#:~:text=Tinea%20is%20the%20name%20of,or%20even%20from%20a%20pet ↵

- “Impetigo2020.jpg” by James Heilman, MD is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- "Lymphedema_limbs.JPG" by medical doctors is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- "Adaptive_Kompressionsbandage_mit_Fußteil.jpg" by Enter is in the Public Domain ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2020, Aug 27]. Lymphedema; [reviewed 2019, Jan 22; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/lymphedema.html ↵

- “Cholangitis Jaundice.jpg” by Bobjgalindo is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [updated 2019, Oct 22]. Jaundice; [reviewed 2016, Aug 31; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/jaundice.html ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2020. Preventing pressure ulcers; [updated 2020, Sep 16; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000147.htm ↵

- “Decubitus 01.jpg” by AfroBrazilian is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “Purpura.jpg” by User:Hektor is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2020. Bleeding into the skin; [updated 2020, Sep 16; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003235.htm ↵

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

1. During a musculoskeletal assessment, the nurse has the patient simultaneously resist against exerted force with both upper extremities. The nurse knows this it is important to perform this assessment on both extremities simultaneously for what reason?

- It measures muscle strength symmetry.

- It provides a more accurate reading.

- It involves more muscle use.

- It decreases assessment time.

2. The nurse is testing upper body strength on an adolescent. The test indicates full ROM against gravity and full resistance. How does the nurse document these assessment findings according to the muscle strength scale?

- 4 out of 5

- 3 out of 5

- 5 out of 5

- 1 out of 5

3. A young adult presents to the urgent care with a right knee injury. The injury occurred during a basketball game. The nurse begins to perform a musculoskeletal assessment. What is the first step of the assessment?

- Palpation

- Inspection

- Percussion

- Auscultation

The intramuscular (IM) injection route is used to place medication in muscle tissue. Muscle has an abundant blood supply that allows medications to be absorbed faster than the subcutaneous route.

Factors that influence the choice of muscle to use for an intramuscular injection include the patient’s size, as well as the amount, viscosity, and type of medication. The length of the needle must be long enough to pass through the subcutaneous tissue to reach the muscle, so needles up to 1.5 inches long may be selected. However, if a patient is thin, a shorter needle length is used because there is less fat tissue to advance through to reach the muscle. Additionally, the muscle mass of infants and young children cannot tolerate large amounts of medication volume. Medication fluid amounts up to 0.5-1 mL can be injected in one site in infants and children, whereas adults can tolerate 2-5 mL. Intramuscular injections are administered at a 90-degree angle. Research has found administering medications at 10 seconds per mL is an effective rate for IM injections, but always review the drug administration rate per pharmacy or manufacturer’s recommendations.[2]

Anatomic Sites

Anatomic sites must be selected carefully for intramuscular injections and include the ventrogluteal, vastus lateralis, and the deltoid. The vastus lateralis site is preferred for infants because that muscle is most developed. The ventrogluteal site is generally recommended for IM medication administration in adults, but IM vaccines may be administered in the deltoid site. Additional information regarding injections in each of these sites is provided in the following subsections.

Ventrogluteal

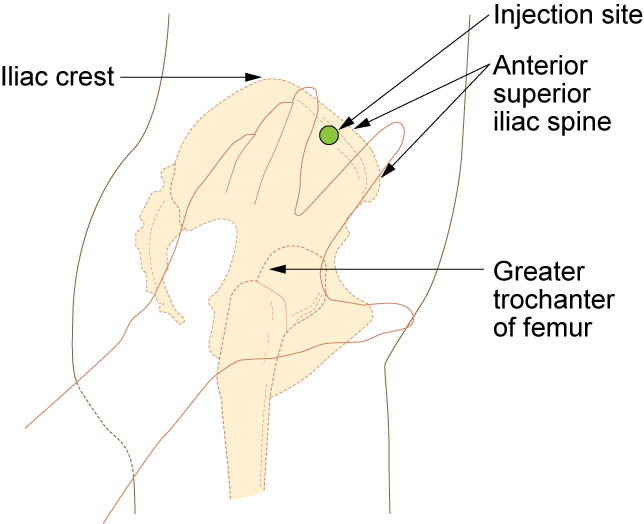

This site involves the gluteus medius and minimus muscle and is the safest injection site for adults and children because it provides the greatest thickness of gluteal muscles, is free from penetrating nerves and blood vessels, and has a thin layer of fat. To locate the ventrogluteal site, place the patient in a supine or lateral position. Use your right hand for the left hip or your left hand for the right hip. Place the heel or palm of your hand on the greater trochanter, with the thumb pointed toward the belly button. Extend your index finger to the anterior superior iliac spine and spread your middle finger pointing towards the iliac crest. Insert the needle into the "V" formed between your index and middle fingers. This is the preferred site for all oily and irritating solutions for patients of any age.[3] See Figure 18.31[4] for an image demonstrating how to accurately locate the ventrogluteal site using your hand.

The needle gauge used at the ventrogluteal site is determined by the solution of the medication ordered. An aqueous solution can be given with a 20- to 25-gauge needle, whereas viscous or oil-based solutions are given with 18- to 21-gauge needles. The needle length is based on patient weight and body mass index. A thin adult may require a 5/8-inch to 1-inch (16 mm to 25 mm) needle, while an average adult may require a 1-inch (25 mm) needle, and a larger adult (over 70 kg) may require a 1-inch to 1½-inch (25 mm to 38 mm) needle. Children and infants require shorter needles. Refer to agency policies regarding needle length for infants, children, and adolescents. Up to 3 mL of medication may be administered in the ventrogluteal muscle of an average adult and up to 1 mL in children. See Figure 18.32[5] for an image of locating the ventrogluteal site on a patient.

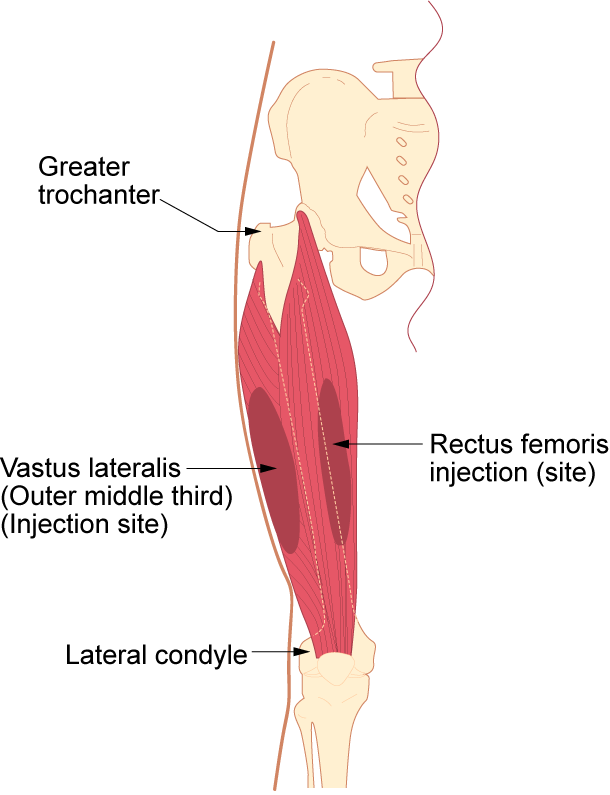

Vastus Lateralis

The vastus lateralis site is commonly used for immunizations in infants and toddlers because the muscle is thick and well-developed. This muscle is located on the anterior lateral aspect of the thigh and extends from one hand’s breadth above the knee to one hand’s breadth below the greater trochanter. The outer middle third of the muscle is used for injections. To help relax the patient, ask the patient to lie flat with knees slightly bent or have the patient in a sitting position. See Figure 18.33[6] for an image of the vastus lateralis injection site.

The length of the needle used at the vastus lateralis site is based on the patient’s age, weight, and body mass index. In general, the recommended needle length for an adult is 1 inch to 1 ½ inches (25 mm to 38 mm), but the needle length is shorter for children. Refer to agency policy for pediatric needle lengths. The gauge of the needle is determined by the type of medication administered. Aqueous solutions can be given with a 20- to 25-gauge needle; oily or viscous medications should be administered with 18- to 21-gauge needles. A smaller gauge needle (22 to 25 gauge) should be used with children. The maximum amount of medication for a single injection in an adult is 3 mL. See Figure 18.34[7] for an image of an intramuscular injection being administered at the vastus lateralis site.

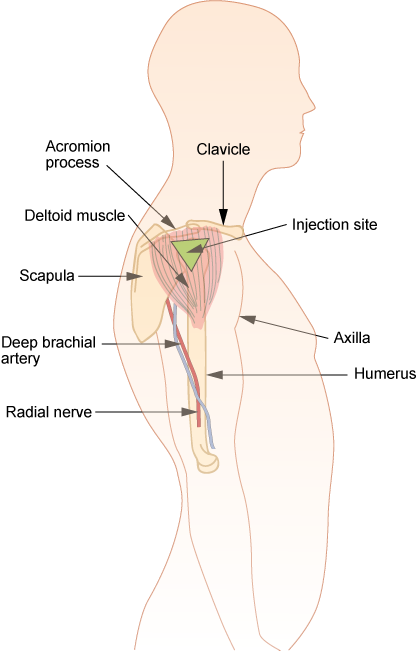

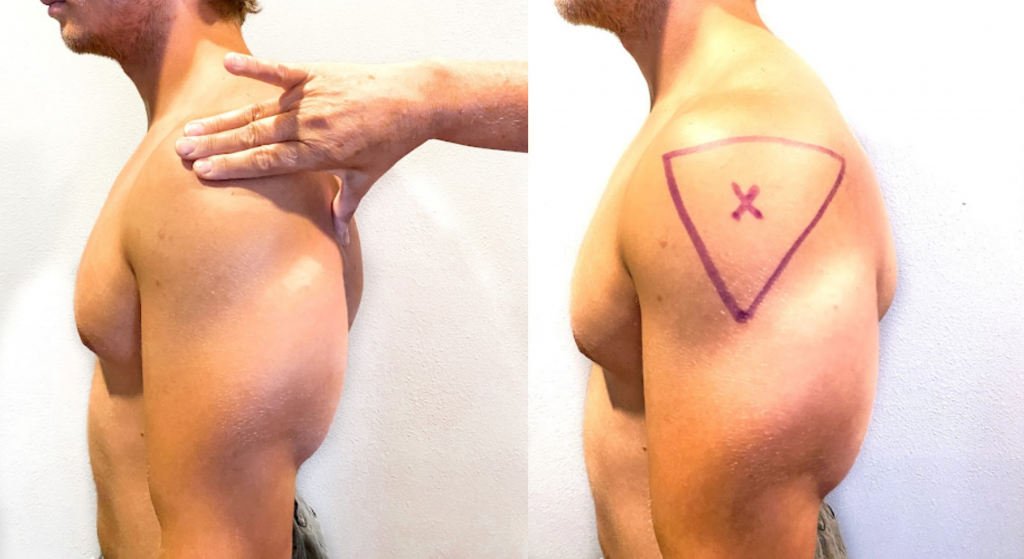

Deltoid

The deltoid muscle has a triangular shape and is easy to locate and access. To locate the injection site, begin by having the patient relax their arm. The patient can be standing, sitting, or lying down. To locate the landmark for the deltoid muscle, expose the upper arm and find the acromion process by palpating the bony prominence. The injection site is in the middle of the deltoid muscle, about 1 inch to 2 inches (2.5 cm to 5 cm) below the acromion process. To locate this area, lay three fingers across the deltoid muscle and below the acromion process. The injection site is generally three finger widths below in the middle of the muscle. See Figure 18.35[8] for an illustration for locating the deltoid injection site.

Select the needle length based on the patient’s age, weight, and body mass. In general, for an adult male weighing 60 kg to 118 kg (130 to 260 lbs), a 1-inch (25 mm) needle is sufficient. For women under 60 kg (130 lbs), a ⅝-inch (16 mm) needle is sufficient, while for women between 60 kg and 90 kg (130 to 200 lbs) a 1-inch (25 mm) needle is required. A 1 ½-inch (38 mm) length needle may be required for women over 90 kg (200 lbs) for a deltoid IM injection. For immunizations, a 22- to 25-gauge needle should be used. Refer to agency policy regarding specifications for infants, children, adolescents, and immunizations. The maximum amount of medication for a single injection is generally 1 mL. See Figure 18.36[9] for an image of locating the deltoid injection site on a patient.

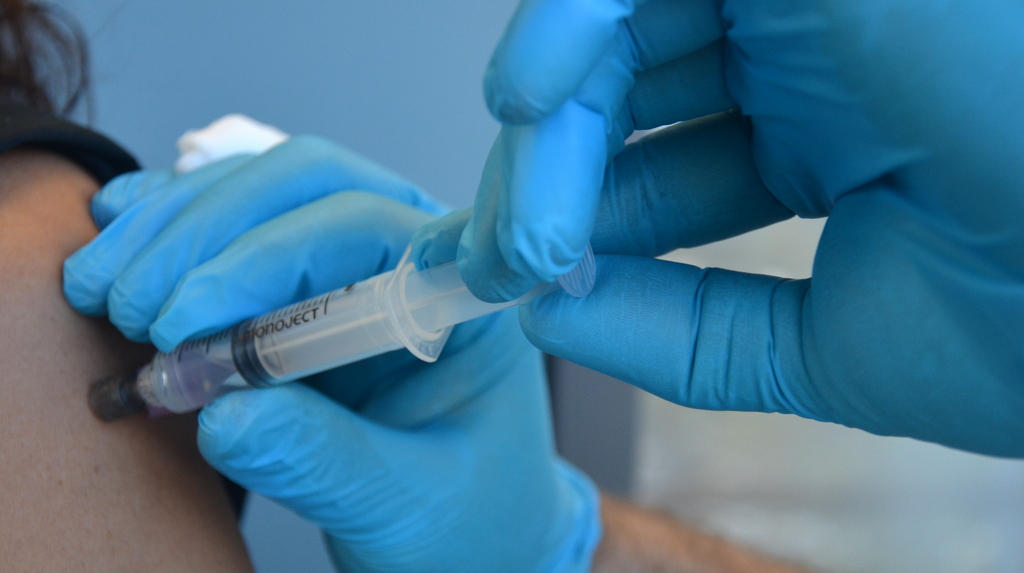

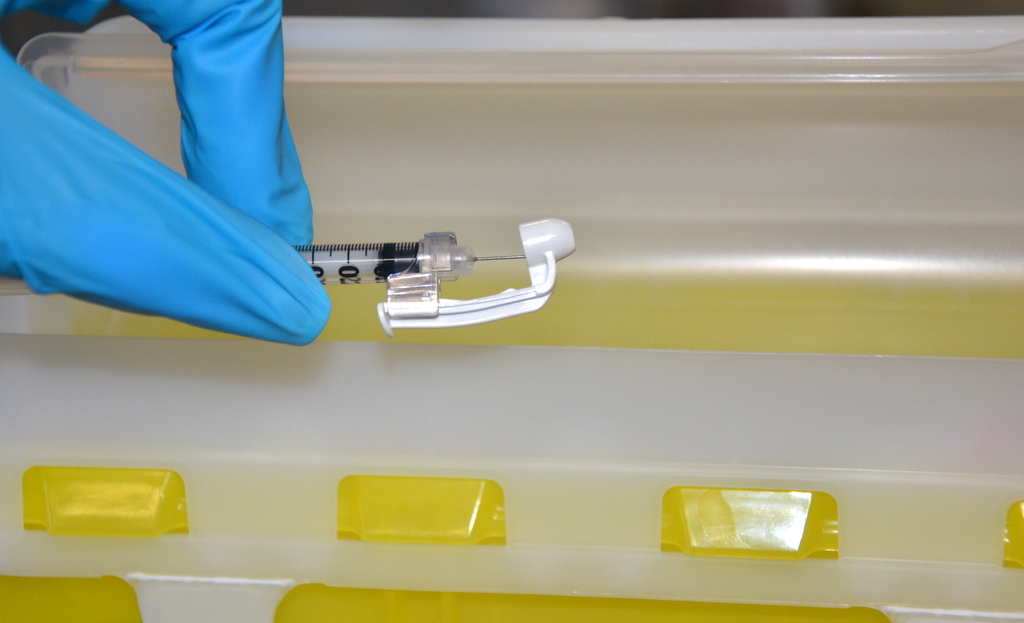

Description of Procedure

When administering an intramuscular injection, the procedure is similar to a subcutaneous injection, but instead of pinching the skin, stabilize the skin around the injection site with your nondominant hand. With your dominant hand, hold the syringe like a dart and inject the needle quickly into the muscle at a 90-degree angle using a steady and smooth motion. After the needle pierces the skin, use the thumb and forefinger of the nondominant hand to hold the syringe. If aspiration is indicated according to agency policy and manufacturer recommendations, pull the plunger back to aspirate for blood. If no blood appears, inject the medication slowly and steadily. If blood appears, discard the syringe and needle and prepare the medication again. See Figure 18.37[10] for an image of aspirating for blood. After the medication is completely injected, leave the needle in place for ten seconds, then remove the needle using a smooth, steady motion. Remove the needle at the same angle at which it was inserted. Cover the injection site with sterile gauze using gentle pressure and apply a Band-Aid if needed.[11]

Z-track Method for IM injections

Evidence-based practice supports using the Z-track method for administration of intramuscular injections. This method prevents the medication from leaking into the subcutaneous tissue, allows the medication to stay in the muscles, and can minimize irritation.[13]

The Z-track method creates a zigzag path to prevent medication from leaking into the subcutaneous tissue. This method may be used for all injections or may be specified by the medication.

Displace the patient’s skin in a Z-track manner by pulling the skin down or to one side about 1 inch (2 cm) with your nondominant hand before administering the injection. With the skin held to one side, quickly insert the needle at a 90-degree angle. After the needle pierces the skin, continue pulling on the skin with the nondominant hand, and at the same time, grasp the lower end of the syringe barrel with the fingers of the nondominant hand to stabilize it. Move your dominant hand and pull the end of the plunger to aspirate for blood, if indicated. If no blood appears, inject the medication slowly. Once the medication is given, leave the needle in place for ten seconds. After the medication is completely injected, remove the needle using a smooth, steady motion, and then release the skin. See Figure 18.38[14] for an illustration of the Z-track method.

![“Z-track-process-1.png“ and "Z-track-process-3.png" by British Columbia Institute of Technology (BCIT) is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/chapter/6-8-iv-push-medications-and-saline-lock-flush/[/footnote] Illustration showing two parts of the Z track method](https://nicoletcollege.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/54/2022/04/ztrack-1-1024x409.png)

Special Considerations for IM Injections

- Avoid using sites with atrophied muscle because they will poorly absorb medications.

- If repeated IM injections are given, sites should be rotated to decrease the risk of hypertrophy.

- Older adults and thin patients may only tolerate up to 2 milliliters in a single injection.

- Choose a site that is free from pain, infection, abrasions, or necrosis.

- The dorsogluteal site should be avoided for intramuscular injections because of the risk for injury. If the needle inadvertently hits the sciatic nerve, the patient may experience partial or permanent paralysis of the leg.

Video Reviews of Administering Intramuscular Injections:

Z-Track Method[15]

IM injection Ventrogluteal Site[16]

Video Reviews of Crushing Medications, Pill Splitting, and Administering Rectal Suppositories:

Crushing Medications[17]

Splitting Pill in Half[18]

View Agrace Hospice Care's Giving Meds by Suppository video on YouTube[19]

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities'" can be found in the '"Answer Key'" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

1. A physician has ordered nafcillin 750 mg IM q 6 h. On hand is a 2 gram vial that states: “Add 6.8 mL of sterile water to provide a total solution of 8 mL.” How many milliliters should the nurse draw up to give the patient the ordered dose?

2. What are the steps the nurse should follow if the medication is given to the wrong patient?

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of the "NG Suction."

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Verify the provider’s order.

- Gather supplies: nonsterile gloves.

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient and ask if they have any questions.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs.

- Don the appropriate PPE as indicated.

- Perform abdominal and nasogastric tube assessment:

- Assess skin integrity on the nose and ensure the tube is securely attached.

- Use a flashlight to look in the nares to assess swelling, redness, or bleeding.

- Ask the patient to open their mouth and look for curling of the tube in the patient’s mouth. The tube should go straight down into the esophagus.

- Lower the blankets and move the gown up to expose the abdomen. Inspect from two locations.

- Auscultate bowel sounds and then palpate the abdomen.

Rationale: Performing a nasogastric and abdominal assessment is important for determining signs of complications such as skin breakdown and necessity for suction.

- Don gloves.

- Attach the NG tube to the suction canister.

- Set the rate of suction according to provider order:

- Low intermittent suction is usually ordered. Low range on the suction device is from 0 to 80 mmHg. Starting between 40-60 mmHg is recommended. The suction level should not exceed 80 mmHg.

- Observe for the gastric content to flow into the tubing and then the canister.

- Monitor canister output and document color, odor, consistency, and amount.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Document the procedure and related assessment findings. Report any concerns according to agency policy.

Assessments Prior to Injection Administration

When administering any parenteral injection, the nurse assesses the patient prior to administration for safe medication administration. See Table 18.7 to review assessments prior to medication administration.

Table 18.7 Assessments Prior to Injection Administration

| Assessment | Rationale/Considerations |

|---|---|

| Check the MAR with the written medication prescription for accuracy and completeness. | Prevent medication errors. |

| Perform the rights of medication administration, including patient’s name, medication name and dose, route, time of administration, and verify the expiration date.

Label syringes with medication names as you prepare them. |

Prevent medication errors.

Discard medication if expired. Label syringes during the procedure to administer medications safely according to the Joint Commission.[20] |

| Assess and review a patient's current medical condition, past medical history, and medication history. | Identify the need for the medication, as well as any possible contraindications for the administration of prescribed medication to the specific patient. |

| Assess the patient's history of medication allergies or nondrug allergies that may interfere with the medication. If there is a history of allergic reactions, document the type of reaction if possible (e.g., hives, rash, swelling, difficulty breathing). If there is an allergy to prescriber medication, do not prepare it and notify the prescribing provider. | Safely administer medication. |

| Review a current, evidence-based drug reference to determine medication action, indication for medication, normal dosage range, and potential side effects. Identify peak and onset times, as well as any nursing considerations. | Safely administer medication and plan to monitor the patient’s response. For example, by knowing the peak onset of fast-acting insulin, the nurse anticipates when the patient may be most at risk for a hypoglycemic reaction. |

| Review and assess pertinent laboratory results (i.e., blood glucose, prothrombin times). Be aware of abnormal kidney and liver function results because they may affect metabolism of medication. Notify the prescriber of any concerns. | Collect data to determine if the medication should be withheld to ensure proper dosage and to establish a baseline for measuring the patient’s response to the drug. |

| Observe the patient’s verbal and nonverbal reactions to the injection. | Be aware of the patient’s level of anxiety and use distractions and other therapeutic techniques to reduce pain and anxiety. |

| Perform patient assessments, such as vital signs, lung sounds, or pain level, as indicated, prior to medication administration. | Obtain baseline data to ensure medication administration is appropriate at this time and to establish a baseline for measuring the patient’s response to the medication. |

| Assess for contraindications to subcutaneous or intramuscular injections such as muscle atrophy or decreased blood flow to the tissue. | Assess for contraindications because reduced muscle and blood flow interfere with the drug absorption and distribution. |

| Assess the patient’s knowledge of the medication. | Perform patient education about the medication as needed. |

| Assess the skin and tissue quality around the area of the intended injection site. Note any bruising, nonintact skin, abrasions, masses, or scar tissue. Avoid these areas and choose another recommended location. | Assess skin and tissue quality to avoid unnecessary or further injury to the already compromised skin integrity. Areas that are scarred or atrophied can affect the absorption and distribution of the medication. |

Evaluation

Nurses evaluate for possible complications of parenteral medication administration that may occur as a result of a medication error or as an adverse reaction. Complications may occur if a medication is prepared incorrectly, if the medication is injected incorrectly, or if an adverse effect occurs after the medication is injected. Unexpected outcomes can occur such as nerve or tissue damage, ineffective absorption of the medication, pain, bleeding, or infection.

An adverse reaction may develop as a result of an injected medication. An adverse reaction may also occur despite appropriate administration of medication and can happen for various reasons. A reaction may be evident within minutes or days after the exposure to the injectable medication. An unexpected outcome may range from a minor reaction, like a skin rash, to serious and life-threatening events such as anaphylaxis, hemorrhaging, and even death.

If a suspected complication occurs during administration, immediately stop the injection. Assess and monitor vital signs, notify the health care provider, and document an incident report.

If a small amount of a fresh urine is needed for specimen collection for urinalysis or culture, aspirate the urine from the needleless sampling port with a sterile syringe after cleansing the port with a disinfectant.[21]See the "Checklist for Obtaining a Urine Specimen from a Foley Catheter" for more detailed instructions. Do not collect the urine that is already in the collection bag because it is contaminated and will lead to an erroneous test result.

Patient reports post-surgical pain at a level of 8/10. Patient is grimacing when moving in the bed and describes pain as a dull constant ache located in the right lower abdomen surgical incision area that is aggravated by moving or repositioning. Blood pressure 146/80, heart rate 94 bpm, respirations 22 per minute, temperature (tympanic) 98.8°F, pulse oximetry 98%. Last pain medication Ketorolac 30 mg (IM) given 8 hours ago. Incision site is dry and intact. Ketorolac 30mg IM administered per health provider’s prescription in the left ventrogluteal area with 22-gauge needle, length 1 ½ inches. Patient tolerated the procedure without difficulty or increased pain. Injection site post-procedure without bleeding or hematoma.

Subcutaneous injections are administered into the adipose tissue layer called “subcutis” below the dermis. See an image of the subcutis (hypodermis) layer in Figure 18.20.[22] Medications injected into the subcutaneous layer are absorbed at a slow and steady rate.

Anatomic Sites

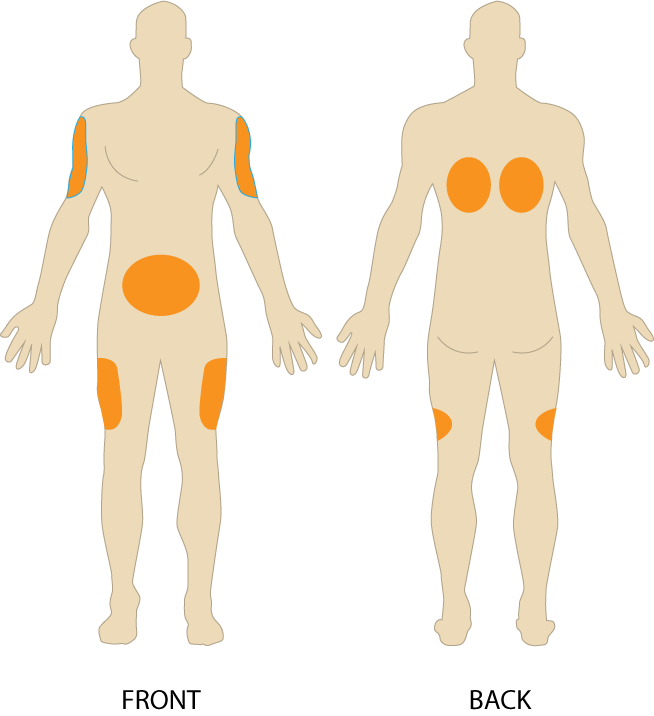

Sites for subcutaneous injections include the outer lateral aspect of the upper arm, the abdomen (from below the costal margin to the iliac crest and more than two inches from the umbilicus), the anterior upper thighs, the upper back, and the upper ventral gluteal area.[23] See Figure 18.21[24] for an illustration of commonly used subcutaneous injection sites. These areas have large surface areas that allow for rotation of subcutaneous injections within the same site when applicable.

Prior to injecting the medication, inspect the skin area. Avoid skin areas that are bruised, open, scarred, or over bony prominences. Medical conditions that impair the blood flow to a tissue area contraindicate the use of subcutaneous injections in that area. For example, if a patient has an infection in an area of their skin called “cellulitis,” then subcutaneous injections should not be given in that area.

Description of Procedure

Nurses select the appropriate needle size for subcutaneous injection based on patient size. Subcutaneous needles range in gauge from 25-31 and in length from ½ inch to ⅝ inch. Prior to administering the injection, determine the amount of subcutaneous tissue present and use this information to select the needle length. A 45- or 90-degree angle is used for a subcutaneous injection. A 90-degree angle is used for normal-sized adult patients or obese patients, and a 45-degree angle is used for patients who are thin or have with less adipose tissue at the injection site. The volume of solution in a subcutaneous injection should be no more than 1 mL for adults and 0.5 mL for children. Larger amounts may not be absorbed appropriately and may cause increased discomfort for the patient.[25]

When administering a subcutaneous injection, assess the patient for any contraindications for receiving the medication. Apply nonsterile gloves after performing hand hygiene to reduce your risk of exposure to blood. Position the patient in a comfortable position and select an appropriate site for injection. Cleanse the site with an alcohol swab or antiseptic swab for 30 seconds using a firm, circular motion, and then allow the site to dry. Allowing the skin to dry prevents introducing alcohol into the tissue, which can be irritating and uncomfortable. Remove the needle cap with the nondominant hand, pulling it straight off to avoid needlestick injury. Grasp and pinch the area selected as an injection site.[26] See Figure 18.22[27] for an image of a nurse grasping the back of a patient’s upper arm with the nondominant hand in preparation of a subcutaneous injection at the anatomical site indicted with an “X.”

Hold the syringe in the dominant hand between the thumb and forefinger like a dart. Insert the needle quickly at a 45- to 90-degree angle, depending on the size of the patient and the amount of adipose tissue. After the needle is in place, release the tissue with your nondominant hand. With your dominant hand, inject the medication at a rate of 10 seconds per mL. Avoid moving the syringe.[28] See Figure 18.23[29] for an image of a subcutaneous injection.

Withdraw the needle quickly at the same angle at which it was inserted. Using a sterile gauze, apply gentle pressure at the site after the needle is withdrawn. Do not massage the site. Massaging after a heparin injection can contribute to the formation of a hematoma. Do not recap the needle to avoid puncturing oneself. Apply the safety shield and dispose of the syringe/needle in a sharps container. See Figure 18.24[30] for an image of a needle after the safety shield has been applied. Remove gloves and perform hand hygiene.[31]

Examples of common medications administered via subcutaneous injection include insulin and heparin. Special considerations for each of these medications are discussed below.

Insulin Injections

Insulin is considered a high-alert medication requiring special care to prevent medication errors. Care must be taken to ensure the correct type and amount of insulin are administered at the correct time. It is highly recommended to have insulin dosages double-checked by another nurse before administration because of the potential for life-threatening adverse effects that can occur due to medication errors. Some agencies require this second safety check.

Only insulin syringes should be used to administer insulin injection. Insulin syringes are supplied in 30-, 50-, or 100-unit measurements, so read the barrel increments (calibration) carefully. Insulin is always ordered and administered in unit dosage. Insulin dosage may be based on the patient’s pre-meal blood sugar reading and a sliding scale protocol that indicates the number of units administered based on the blood sugar reading.[32],[33]

There are rapid-, short-, intermediate-, and long-acting insulins. For each type of insulin, it is important to know the onset, peak, and duration of the insulin so that it can be timed appropriately with the patient’s food intake. It is essential to time the administration of insulin with food intake to avoid hypoglycemia. When administering insulin before a meal, always ensure the patient is not nauseated and is able to eat. Short- or rapid-acting insulin may be administered up to 15-30 minutes before meals. Intermediate insulin is typically administered twice daily, at breakfast and dinner, and long-acting insulin is typically administered in the evening.[34],[35]

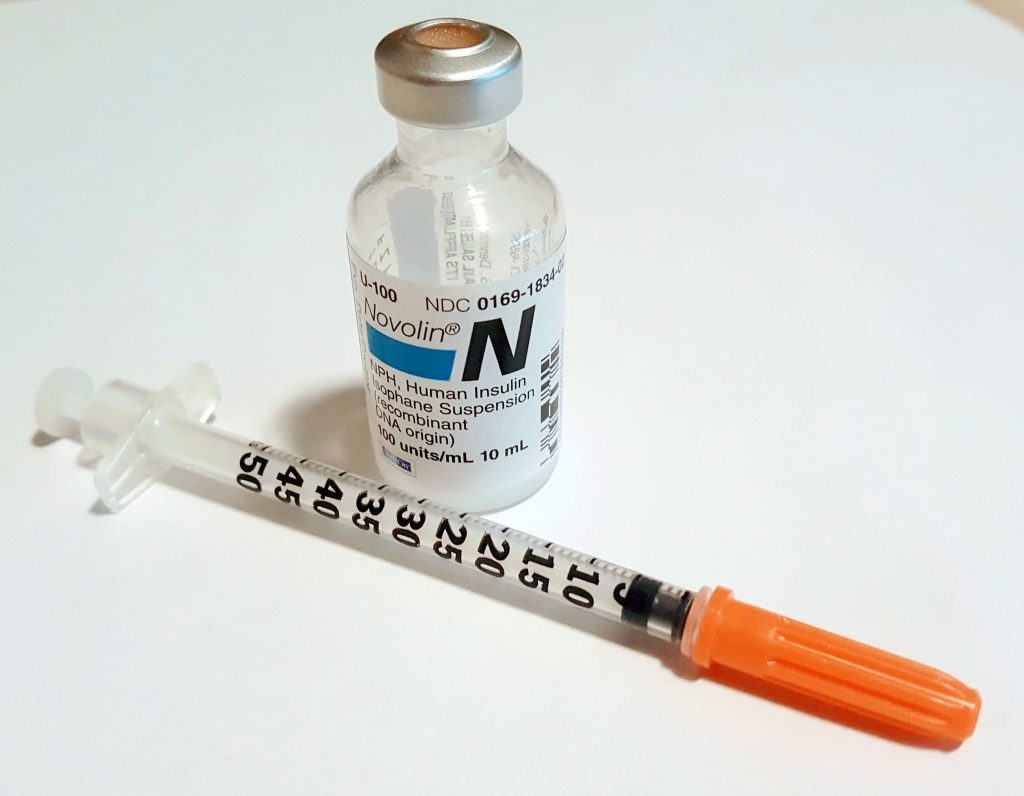

When administering cloudy insulin preparations such as NPH insulin (Humulin-N), gently roll the vial between the palms of your hands to resuspend the medication before withdrawing it from the vial.[36],[37] See Figure 18.25[38] for an image of insulin NPH that is cloudy in color.

Preparing Insulin in a Syringe

When withdrawing insulin from a vial, check the insulin vial to make sure it is the right kind of insulin and that there are no clumps or particles in it. Also, make sure the insulin is not past its expiration date. Pull air into the syringe to match the amount of insulin you plan to remove. Hold the syringe like a pencil and insert the needle into the rubber stopper on the top of the vial. Push the plunger down until all of the air is in the bottle. This helps to keep the right amount of pressure in the bottle and makes it easier to draw up the insulin. With the needle still in the vial, turn the bottle and syringe upside down (vial above syringe). Pull the plunger to fill the syringe to the desired amount. Check the syringe for air bubbles. If you see any large bubbles, push the plunger until the air is purged out of the syringe. Pull the plunger back down to the desired dose. Remove the needle from the bottle. Be careful to not let the needle touch anything until you are ready to inject.[39]

Mixing Two Types of Insulin

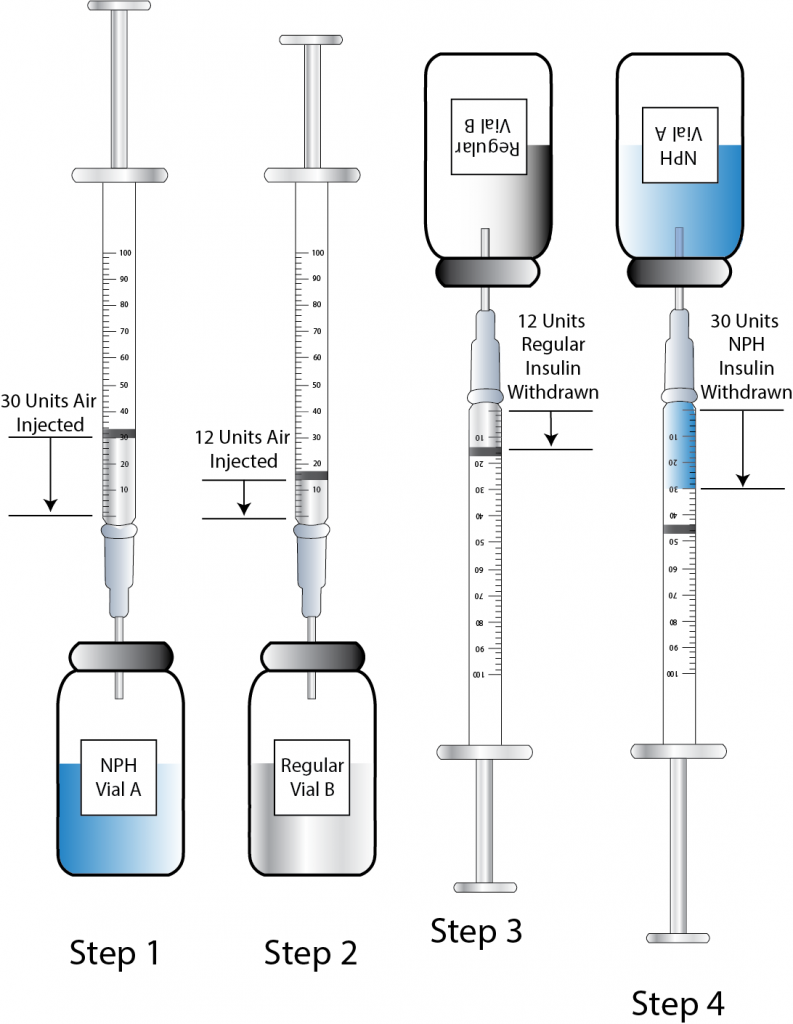

If a patient is ordered two types of insulin, some insulins may be mixed together in one syringe. For example, insulin NPH (Novolin-N) can be mixed with insulin regular (Humulin-R), insulin aspart (Novolog), or insulin lispro (Humalog). However, some types of insulin cannot be mixed with other insulin, such as insulin glargine (Lantus) or insulin detemir (Levemir).[40],[41]

When mixing insulin, gather your insulin supplies. Check the insulin vials to make sure they are the right kinds of insulin, there are no clumps or particles in them, and the expiration dates have not passed. Gently mix intermediate or premixed insulin by turning the vial on its side and rolling it between the palms of your hands. Prepare the insulin vials by injecting air into the intermediate insulin vial. Remove the cap from the needle. With the vial of insulin below the syringe, inject an amount of air equal to the dose of intermediate insulin that you will be taking. Do not draw out the insulin into the syringe yet. Remove the needle from the vial. Inject air into the rapid-acting insulin vial equal to the rapid-acting insulin dose. With the needle still in the vial, turn the vial upside down (vial above the syringe) and pull the plunger to fill the syringe with the desired dose. Check the syringe for air bubbles. If you see any large bubbles, push the plunger until the air is purged out of the syringe. Pull the plunger back down to the desired dose. Remove the needle from the vial and recheck your dose. Insert the needle into the vial of cloudy insulin. Turn the vial upside down (vial above syringe) and pull the plunger to draw the dose of intermediate-acting insulin. Because the short-acting insulin is already in the syringe, pull the plunger to the total number of units you need. Do not inject any of the insulin back into the vial because the syringe now contains a mixture of intermediate- and rapid-acting insulin. Remove the needle from the vial and be careful to not let the needle touch anything until you are ready to inject.[42]

When mixing insulin, it is important to always draw up the short-acting insulin first to prevent it from being contaminated with the long-acting insulin. See Figure 18.26[43] for an illustration of the order to follow when mixing insulin.

One anatomic region should be selected for a patient’s insulin injections to maintain consistent absorption, and then sites should be rotated within that region. The abdomen absorbs insulin the fastest, followed by the arms, thighs, and buttocks. It is no longer necessary to rotate anatomic regions, as was once done, because newer insulins have a lower risk for causing hypertrophy of the skin.[44],[45]

Video Review of Mixing Insulin:[46]

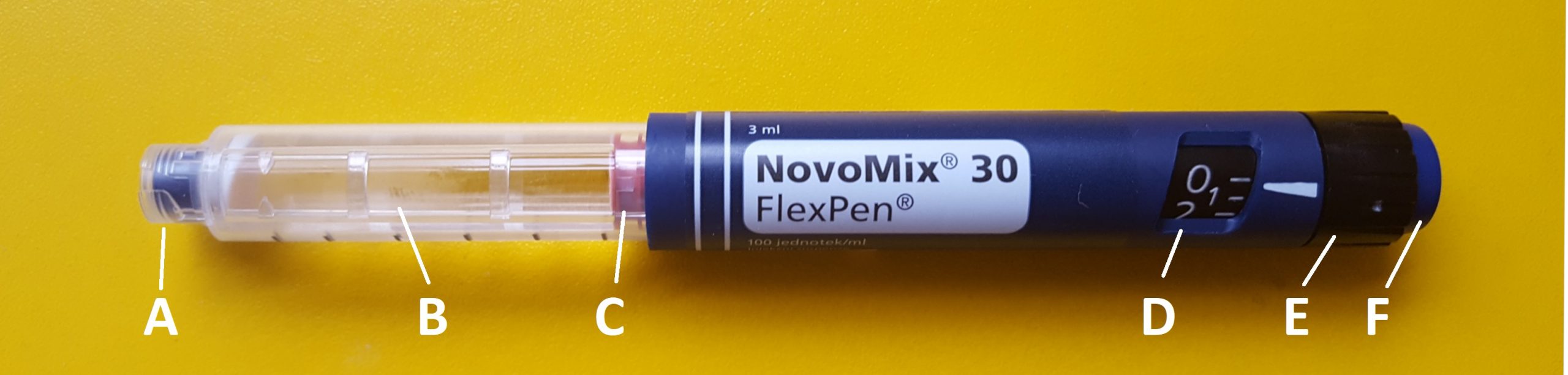

Insulin Pens

Insulin pens are a newer technology designed to be used multiple times for a single person, using a new needle for each injection. See Figure 18.27[47] for an image of an insulin pen. Insulin pens must never be used for more than one person. Regurgitation of blood into the insulin cartridge can occur after injection, creating a risk of blood-borne pathogen transmission if the pen is used for more than one person, even when the needle is changed.[48] Prefilled insulin pens consist of a prefilled cartridge of insulin to which a special, single-use needle is attached. When using an insulin pen for subcutaneous insulin administration, a few additional steps must be taken according to manufacturer guidelines. The needle should be primed with two units of insulin, and then the dosage should be dialed in the dose window. The pen should be held with the hand using four fingers so that the thumb can be used to fully depress the plunger button. The pen should be left in place for ten seconds after the insulin is injected to aid in absorption.[49]

Insulin pens are often prescribed for home use because of their ease of use. Patients and family members must be educated on how to correctly use an insulin pen before discharge. To evaluate a patient’s knowledge of how to correctly administer insulin, ask them to “return demonstrate” the procedure to you.[50],[51]

Special Considerations for Insulin

- Insulin vials are stored in the refrigerator until they are opened. When removed, it should be labelled with an open date and expiration date according to agency policy. When a vial is in use, it should be at room temperature. Do not inject cold insulin because this can cause discomfort.

- Patients who take insulin should monitor their blood sugar (glucose) levels as prescribed by their health care provider.

- Vials of insulin should be inspected prior to use. Any change in appearance may indicate a change in potency. Check the expiration date and do not use it if it has expired.

- All health care workers should be aware of the signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia. Signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia include fruity breath, restlessness, agitation, confusion, slurring of words, clammy skin, inability to concentrate or follow commands, hunger, and nausea. Follow agency policy regarding hypoglycemic reactions.[52]

Insulin Injection Know-HowFor additional details about different types of insulin, hypoglycemia, and safety considerations when administering insulin, visit the "Antidiabetics" section of the "Endocrine" chapter in Open RN Nursing Pharmacology.

Video Review of Mixing Insulin[53]

Heparin Injections

Heparin is an anticoagulant medication used to treat or prevent blood clots. It comes in various strengths and can be administered subcutaneously or intravenously. Heparin is also considered a high-alert medication because of the potential life-threatening harm that can result from a medication error. See Figure 18.28[54] for an image of a prefilled syringe of enoxaparin (Lovenox), a low-molecular weight heparin, that is typically dispensed in prefilled syringes. Review specific guidelines regarding heparin administration in Table 18.5.[55]

Table 18.5 Specific Guidelines for Administering Heparin[56]

| Guidelines | Additional Information |

|---|---|

| Remember that heparin is considered a high-alert medication. | Heparin is available in vials and prefilled syringes in a variety of concentrations. Because of the dangerous adverse effects of the medication, it is considered a high-alert medication. Always follow agency policy regarding the preparation and administration of heparin. |

| Rotate heparin injection sites. | It is important to rotate heparin sites to avoid bruising in one location. Heparin is absorbed best in the abdominal area, at least 2 inches (5 cm.) away from the umbilicus. |

| Know the risks associated with heparin. | There are many risks associated with the administration of heparin, including bleeding, hematuria, hematemesis, bleeding gums, and melena. Monitor, document, and report these side effects when a patient is receiving heparin. |

| Review lab values. | Review lab values (PTT and aPTT) before and after heparin administration. If injecting low-molecular weight heparin (enoxaparin), review platelet count because heparin can cause thrombocytopenia. |

| Follow administration standards for prepackaged heparin and enoxaparin syringes. | Many agencies use prepackaged heparin and enoxaparin syringes. Always follow the standards for safe medication administration when using prefilled syringes. |

| Assess patient conditions prior to administration. | Some medical conditions increase the patient’s risk for hemorrhage (severe bleeding), such as recent childbirth, severe kidney and liver disease, cerebral or aortic aneurysm, and cerebral vascular accidents (CVA). |

| Assess other medications and diet. | Over-the-counter (OTC) herbal medications, such as garlic, ginger, and horse chestnut, may interact with heparin. Additional medications that may interact or cause increased risk of bleeding include aspirin, NSAIDs, cephalosporins, antithyroid agents, thrombolytics, and probenecids. Foods like green leafy vegetables can alter the therapeutic effect of heparin. |

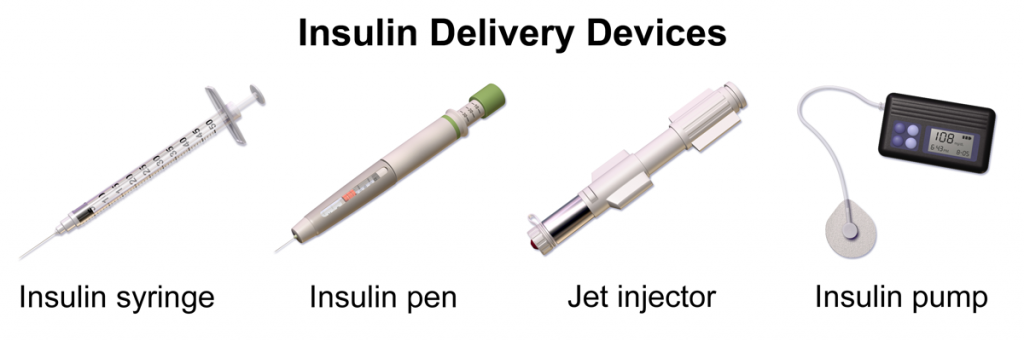

Device Technology

A jet injector is a medical device used for vaccinations and other subcutaneous injections that uses a high-pressure, narrow stream of fluid to penetrate the skin instead of a hypodermic needle. An example of a flu vaccine approved for administration to adults aged 18-64 is AFLURIA © Quadrivalent. The most common injection-site adverse reactions of the jet injector flu vaccine up to seven days post-vaccination were tenderness, swelling, pain, redness, itching, and bruising.[57] Insulin can also be successfully administered via a jet injector, with research demonstrating improved glucose control because the insulin is spread out over a larger area of tissue and enters the bloodstream faster than when administered by an insulin pen or needle. Patients have indicated preference for insulin delivered by the jet injector compared to the insulin pen or syringe because it is needle-free with less tissue injury and pain as compared to the needle injection.[58] See Figure 18.29[59] for an image comparing insulin delivery devices.

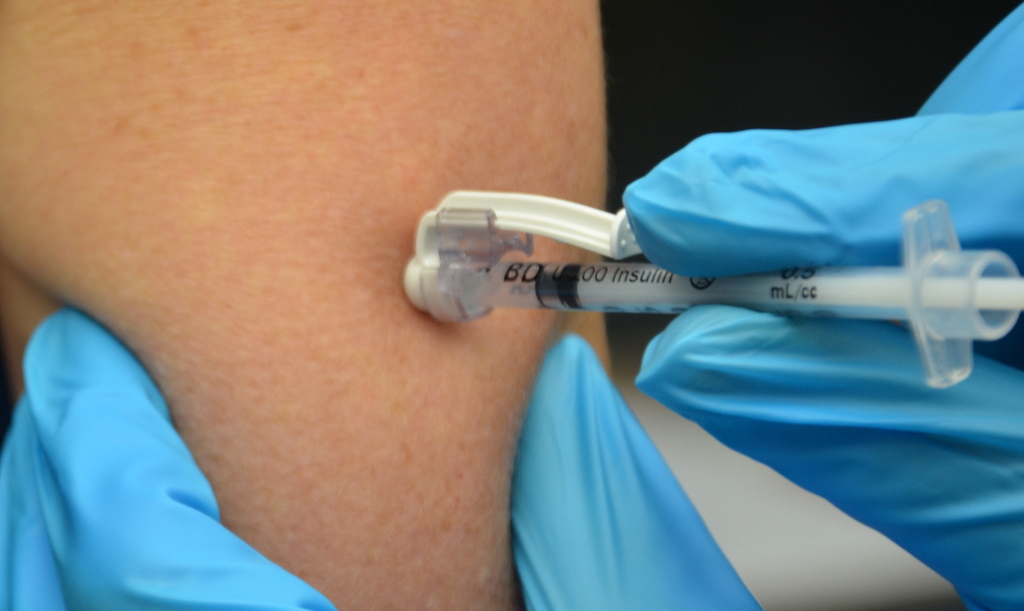

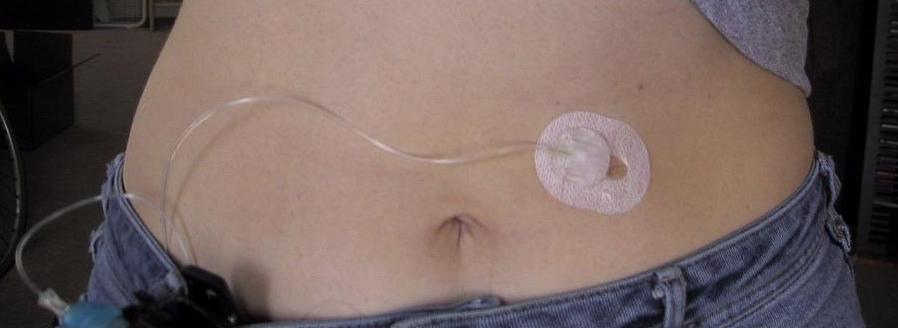

Another type of new technology used to continuously deliver subcutaneous insulin is the insulin pump. Pumps are a computerized device attached to the body, either with tubing or attached to the skin. They are programmed to release small doses of insulin (continuously or as a surge bolus dose) close to mealtime to control the rise in blood sugar after a meal. They work by closely mimicking the body's normal release of insulin. Insulin doses are delivered through a flexible plastic tube called a catheter. With the aid of a small needle, the catheter is inserted through the skin into the fatty tissue and is taped in place.[60] See Figure 18.30[61] for an image of an insulin pump infusion set attached to a patient.

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of “Oropharyngeal Testing.”

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Gather supplies: testing kit or swab, gloves, tongue depressor, and mask. Other PPE such as a face shield, respiratory, or gown may be required based on the patient condition.

- Perform safety steps:

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Check the room for transmission-based precautions.

- Introduce yourself, your role, the purpose of your visit, and an estimate of the time it will take.

- Confirm patient ID using two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth).

- Explain the process to the patient and ask if they have any questions.

- Be organized and systematic.

- Use appropriate listening and questioning skills.

- Listen and attend to patient cues.

- Ensure the patient’s privacy and dignity.

- Assess ABCs.

- Apply nonsterile gloves. Inform the patient the procedure may be uncomfortable and cause gagging.

- Open the supplies.

- Ask the patient to open their mouth wide and tilt their head back.

- Insert the tongue blade to depress the tongue. If the patient can depress their tongue so that it is out of the way of the swab, the tongue blade may not be needed.

- Insert the swab into the posterior pharynx and tonsillar areas. Rub the swab over both tonsillar pillars and posterior oropharynx and avoid touching the tongue, teeth, and gums.

- Place the swab in the sterile tube and snap the end off swab at the break line. Place the cap on the tube.

- Label the tube with the patient's name, date of birth, medical record number, today’s date, your initials, time, and specimen type.

- Place the specimen into the biohazard bag.

- Remove nonsterile gloves and place them in the appropriate receptacle.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Assist the patient to a comfortable position, ask if they have any questions, and thank them for their time.

- Ensure safety measures when leaving the room:

- CALL LIGHT: Within reach

- BED: Low and locked (in lowest position and brakes on)

- SIDE RAILS: Secured

- TABLE: Within reach

- ROOM: Risk-free for falls (scan room and clear any obstacles)

- Follow agency policy regarding transportation of the specimen to the lab. Report results appropriately when they are received.