13.2 Musculoskeletal Basic Concepts

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Skeleton

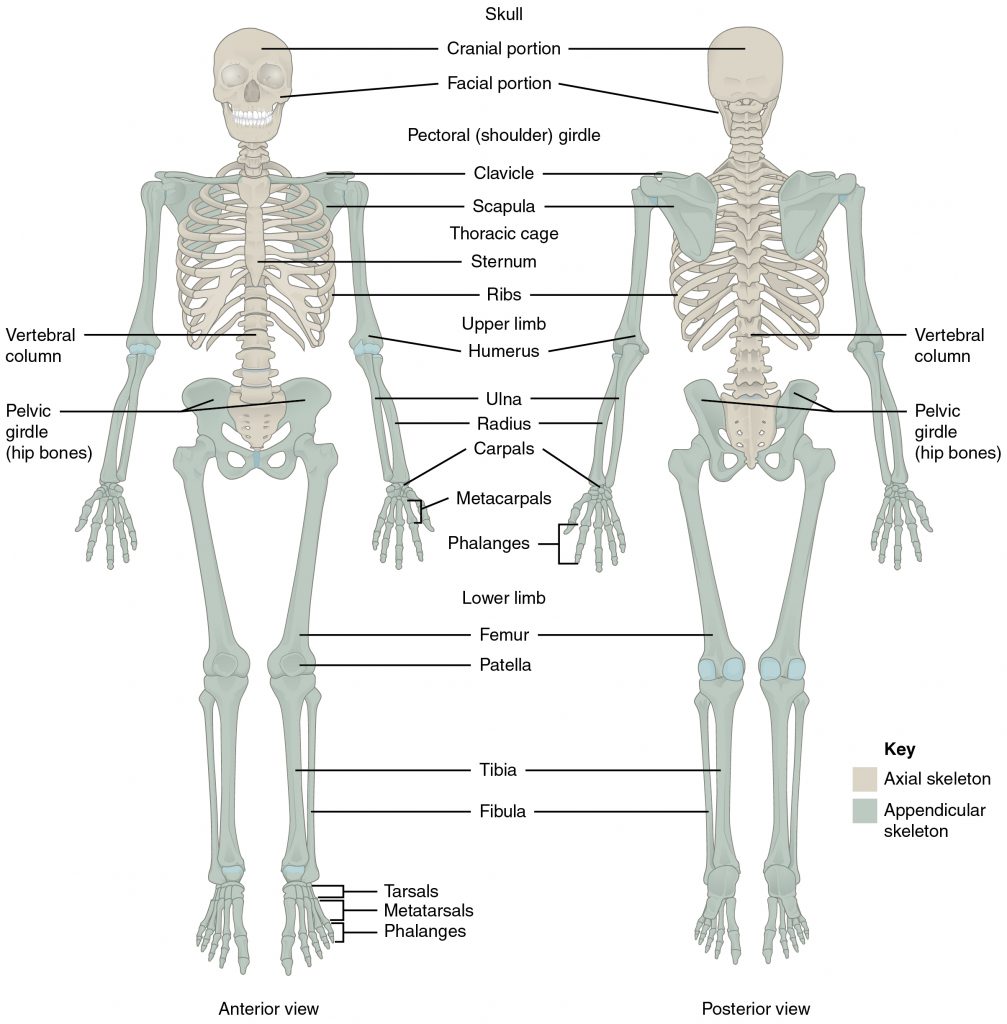

The skeleton is composed of 206 bones that provide the internal supporting structure of the body. See Figure 13.1[1] for an illustration of the major bones in the body. The bones of the lower limbs are adapted for weight-bearing support, stability, and walking. The upper limbs are highly mobile with large range of movements, along with the ability to easily manipulate objects with our hands and opposable thumbs.[2]

Bones are connected together by ligaments. Ligaments are strong bands of fibrous connective tissue that strengthen and support the joint by anchoring the bones together and preventing their separation. Ligaments allow for normal movements of a joint while also limiting the range of these motions to prevent excessive or abnormal joint movements.[3]

Muscles

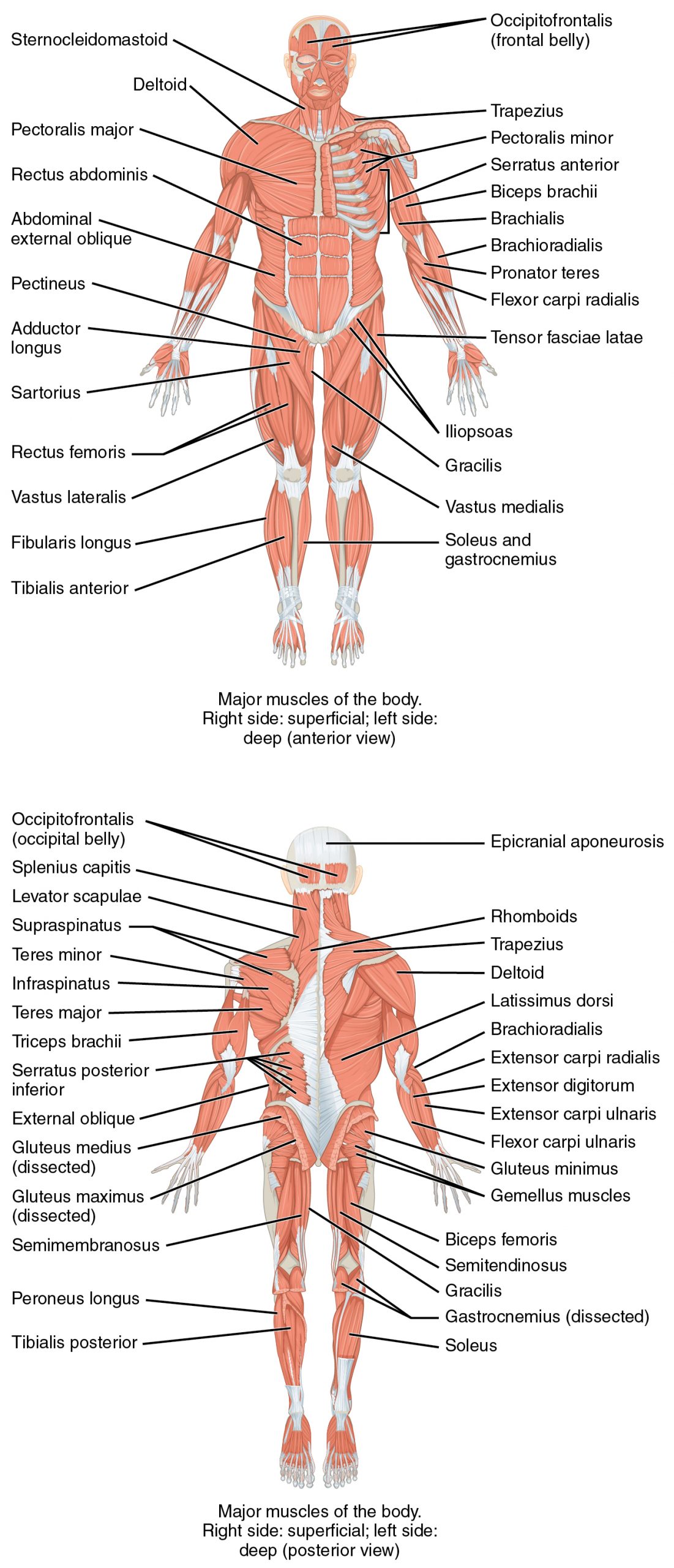

There are three types of muscle tissue: skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, and smooth muscle. Skeletal muscle produces movement, assists in maintaining posture, protects internal organs, and generates body heat. Skeletal muscles are voluntary, meaning a person is able to consciously control them, but they also depend on signals from the nervous system to work properly. Other types of muscles are involuntary and are controlled by the autonomic nervous system, such as the smooth muscle within our bronchioles.[4]

See Figure 13.2[5] for an illustration of skeletal muscle.

To move the skeleton, the tension created by the contraction of the skeletal muscles is transferred to the tendons, strong bands of dense, regular connective tissue that connect muscles to bones.[6]

Muscle Atrophy

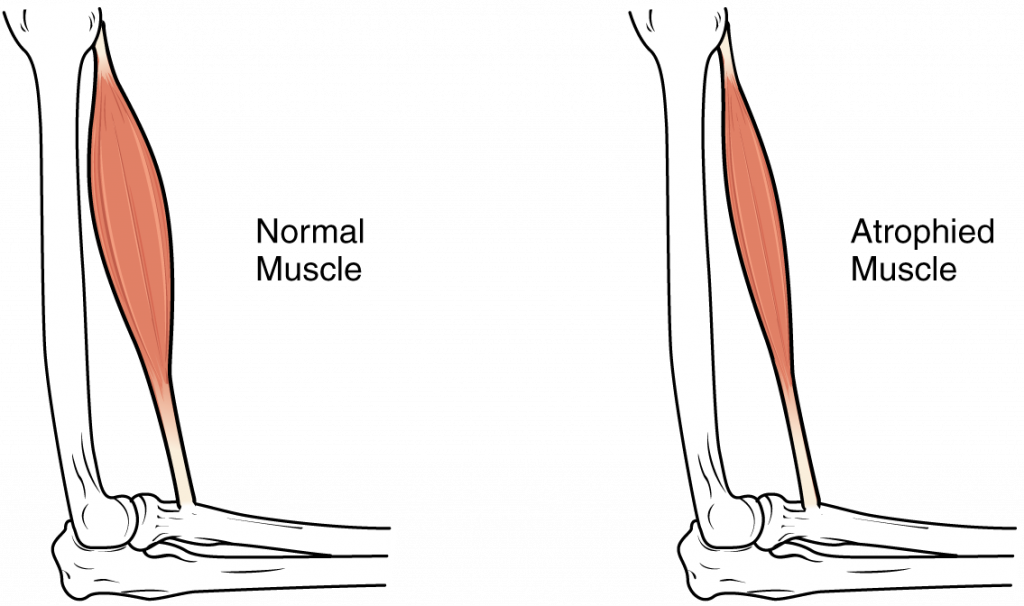

Muscle atrophy is the thinning or loss of muscle tissue. See Figure 13.3[7] for an image of muscle atrophy. There are three types of muscle atrophy: physiologic, pathologic, and neurogenic.

Physiologic atrophy is caused by not using the muscles and can often be reversed with exercise and improved nutrition. People who are most affected by physiologic atrophy are those who:

- Have seated jobs, health problems that limit movement, or decreased activity levels

- Are bedridden

- Cannot move their limbs because of stroke or other brain disease

- Are in a place that lacks gravity, such as during space flights

Pathologic atrophy is seen with aging, starvation, and adverse effects of long-term use of corticosteroids. Neurogenic atrophy is the most severe type of muscle atrophy. It can be from an injured or diseased nerve that connects to the muscle. Examples of neurogenic atrophy are spinal cord injuries and polio.[8]

Although physiologic atrophy due to disuse can often be reversed with exercise, muscle atrophy caused by age is irreversible. The effects of age-related atrophy are especially pronounced in people who are sedentary because the loss of muscle results in functional impairments such as trouble with walking, balance, and posture. These functional impairments can cause decreased quality of life and injuries due to falls.[9]

Joints

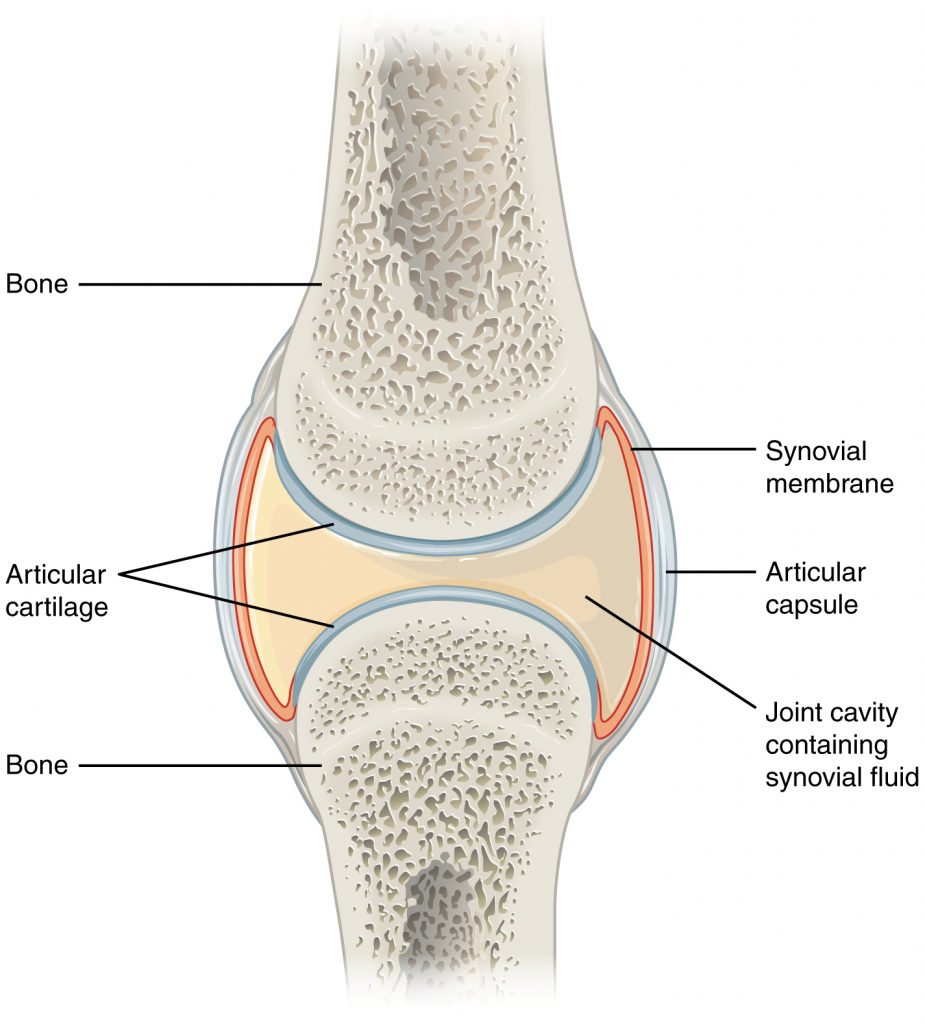

Joints are the location where bones come together. Many joints allow for movement between the bones. Synovial joints are the most common type of joint in the body. Synovial joints have a fluid-filled joint cavity where the articulating surfaces of the bones contact and move smoothly against each other. See Figure 13.4[10] for an illustration of a synovial joint. Articular cartilage is smooth, white tissue that covers the ends of bones where they come together and allows the bones to glide over each other with very little friction. Articular cartilage can be damaged by injury or normal wear and tear. Lining the inner surface of the articular capsule is a thin synovial membrane. The cells of this membrane secrete synovial fluid, a thick, slimy fluid that provides lubrication to further reduce friction between the bones of the joint.[11]

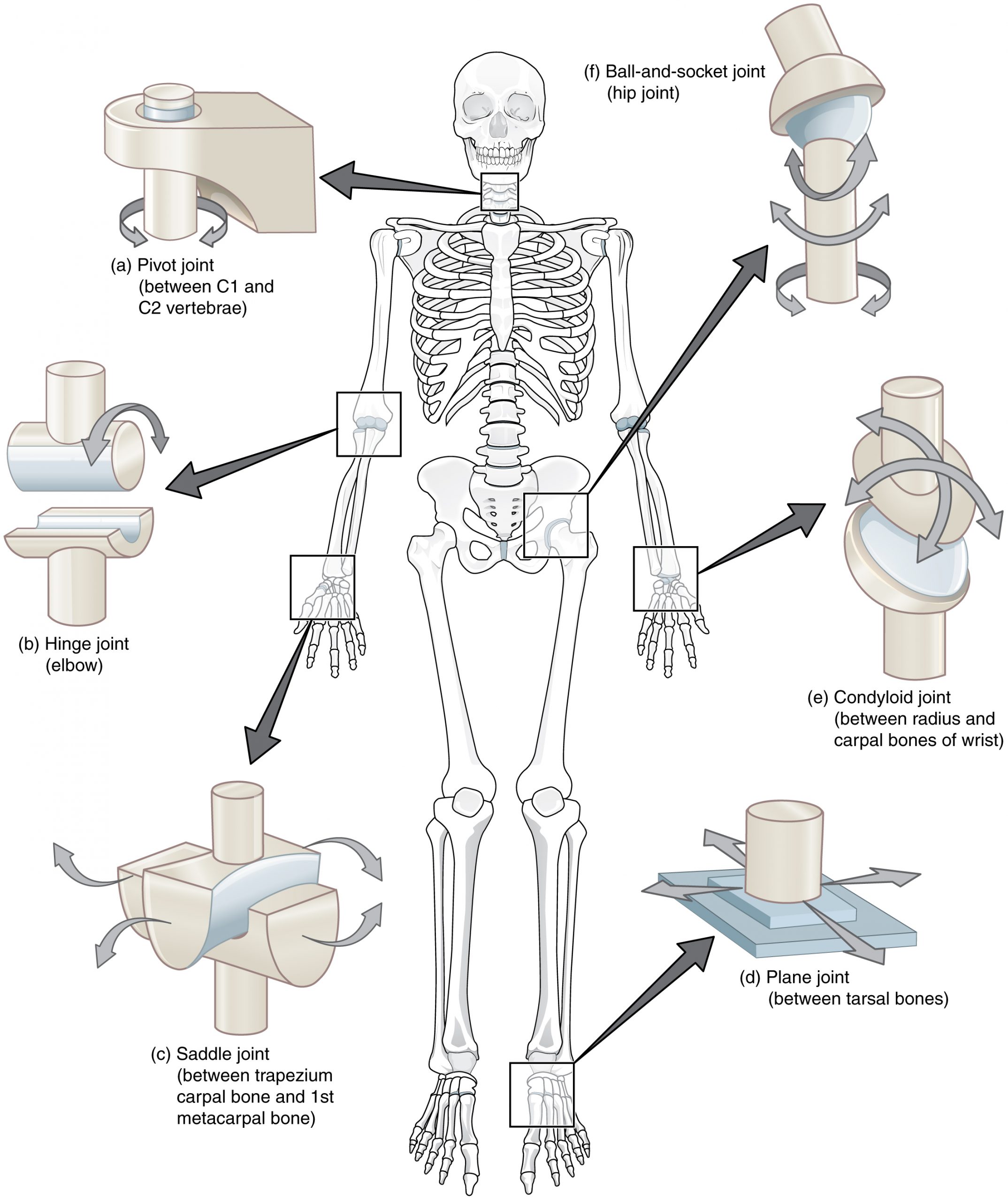

Types of Synovial Joints

There are six types of synovial joints. See Figure 13.5[12] for an illustration of the types of synovial joints. Some joints are relatively immobile but stable. Other joints have more freedom of movement but are at greater risk of injury. For example, the hinge joint of the knee allows flexion and extension, whereas the ball and socket joint of the hip and shoulder allows flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, and rotation. The knee, hip, and shoulder joints are commonly injured and are discussed in more detail in the following subsections.

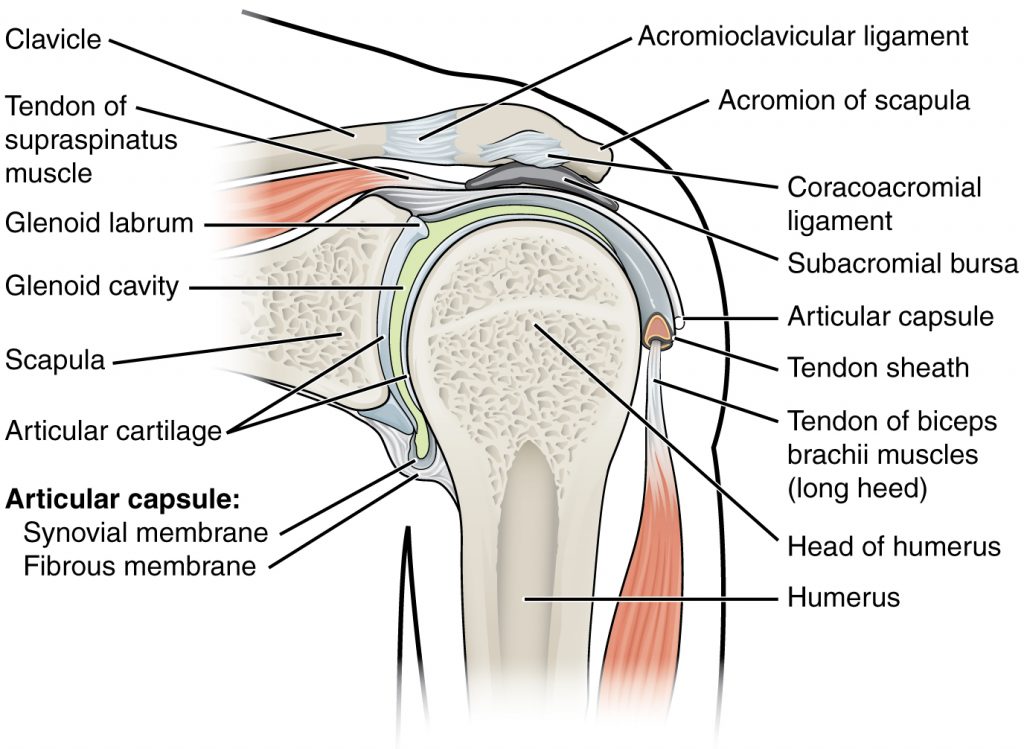

Shoulder Joint

The shoulder joint is a ball-and-socket joint formed by the articulation between the head of the humerus and the glenoid cavity of the scapula. This joint has the largest range of motion of any joint in the body. See Figure 13.6[13] to review the anatomy of the shoulder joint. Injuries to the shoulder joint are common, especially during repetitive abductive use of the upper limb such as during throwing, swimming, or racquet sports.[14]

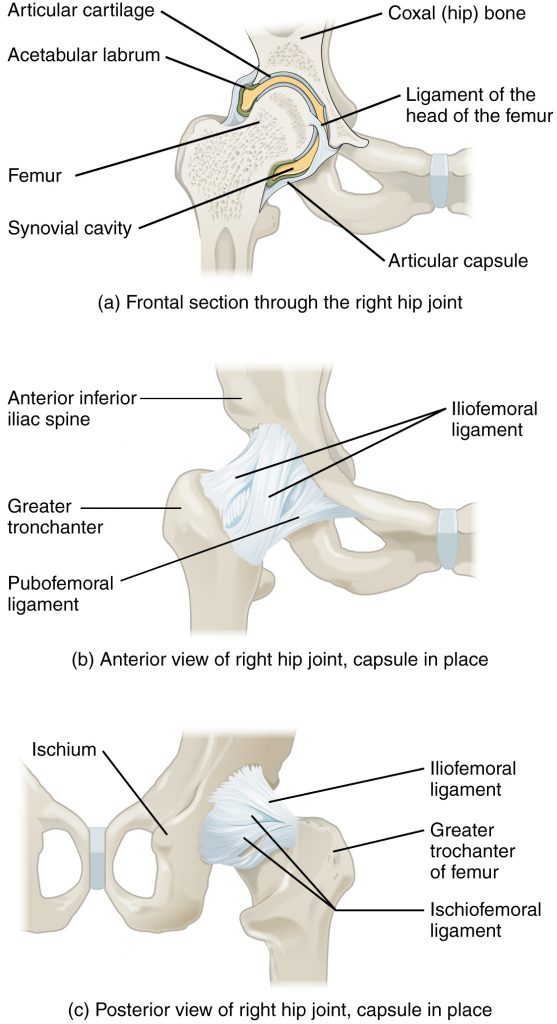

Hip Joint

The hip joint is a ball-and-socket joint between the head of the femur and the acetabulum of the hip bone. The hip carries the weight of the body and thus requires strength and stability during standing and walking.[15]

See Figure 13.7[16] for an illustration of the hip joint.

A common hip injury in older adults, often referred to as a “broken hip,” is actually a fracture of the head of the femur. Hip fractures are commonly caused by falls.[17]

See more information about hip fractures under the “Common Musculoskeletal Conditions” section.

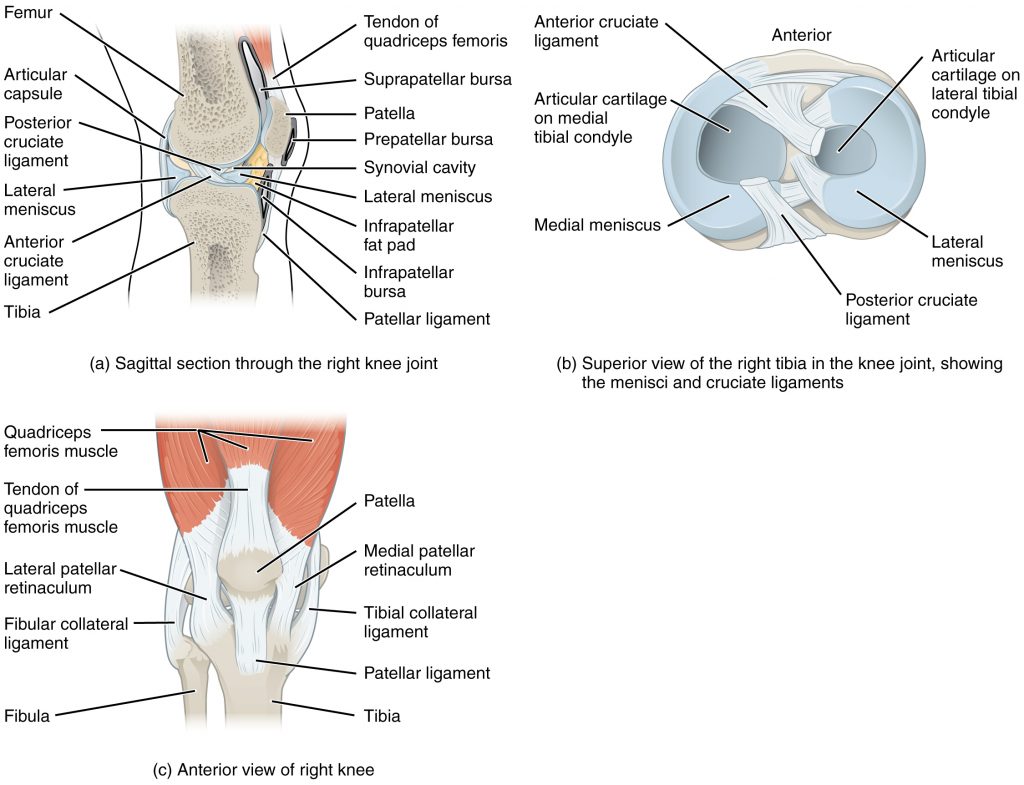

Knee Joint

The knee functions as a hinge joint that allows flexion and extension of the leg. In addition, some rotation of the leg is available when the knee is flexed, but not when extended. See Figure 13.8[18] for an illustration of the knee joint. The knee is vulnerable to injuries associated with hyperextension, twisting, or blows to the medial or lateral side of the joint, particularly while weight bearing.[19]

The knee joint has multiple ligaments that provide support, especially in the extended position. On the outside of the knee joint are the lateral collateral, medial collateral, and tibial collateral ligaments. The lateral collateral ligament is on the lateral side of the knee and spans from the lateral side of the femur to the head of the fibula. The medial collateral ligament runs from the medial side of the femur to the medial tibia. The tibial collateral ligament crosses the knee and is attached to the articular capsule and to the medial meniscus. In the fully extended knee position, both collateral ligaments are taut and stabilize the knee by preventing side-to-side or rotational motions between the femur and tibia.[20]

Inside the knee joint are the anterior cruciate ligament and posterior cruciate ligament. These ligaments are anchored inferiorly to the tibia and run diagonally upward to attach to the inner aspect of a femoral condyle. The posterior cruciate ligament supports the knee when it is flexed and weight-bearing such as when walking downhill. The anterior cruciate ligament becomes tight when the knee is extended and resists hyperextension.[21]

The patella is a bone incorporated into the tendon of the quadriceps muscle, the large muscle of the anterior thigh. The patella protects the quadriceps tendon from friction against the distal femur. Continuing from the patella to the anterior tibia just below the knee is the patellar ligament. Acting via the patella and patellar ligament, the quadriceps is a powerful muscle that extends the leg at the knee and provides support and stabilization for the knee joint.

Located between the articulating surfaces of the femur and tibia are two articular discs, the medial meniscus and lateral meniscus. Each meniscus is a C-shaped fibrocartilage that provides padding between the bones.[22]

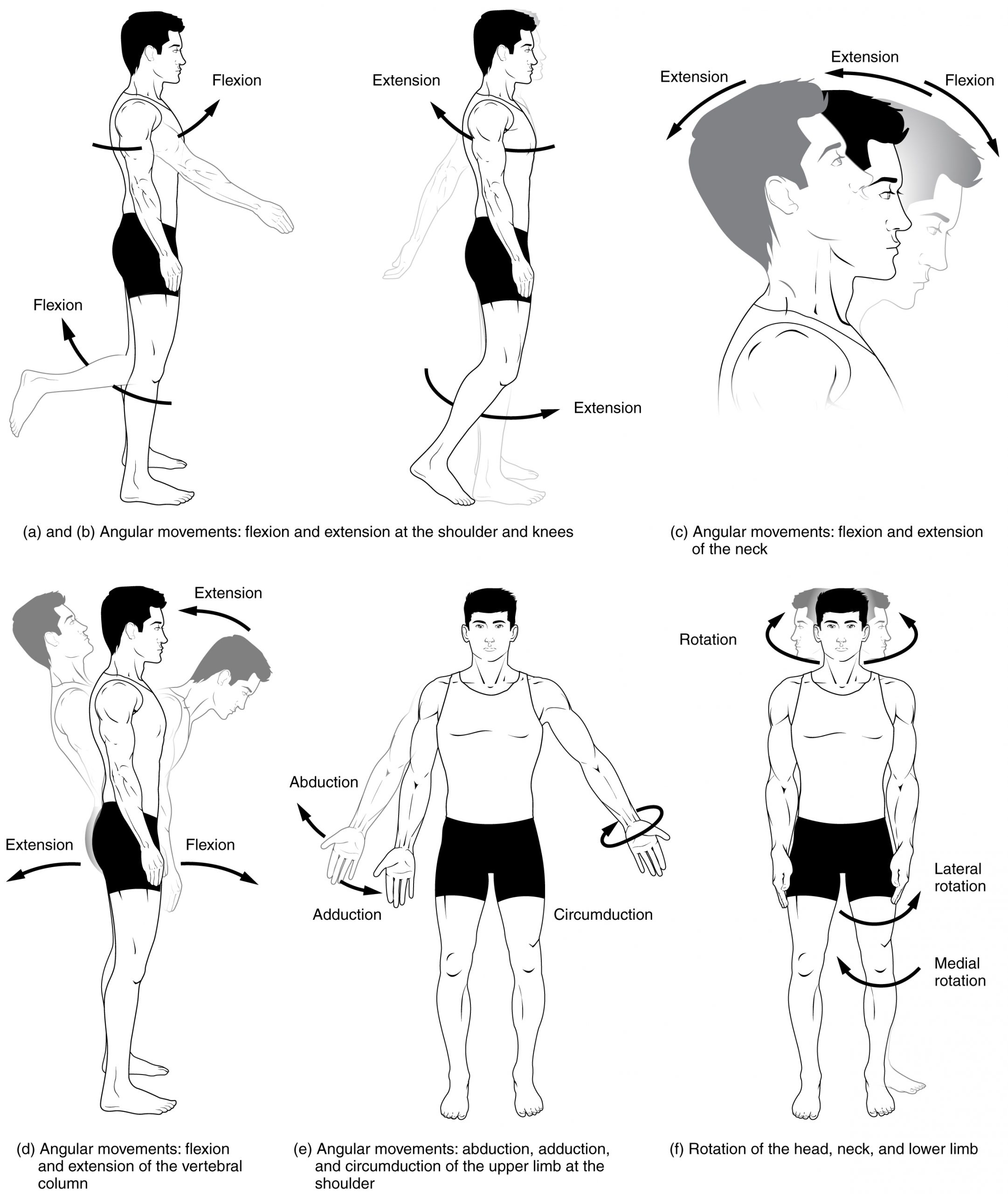

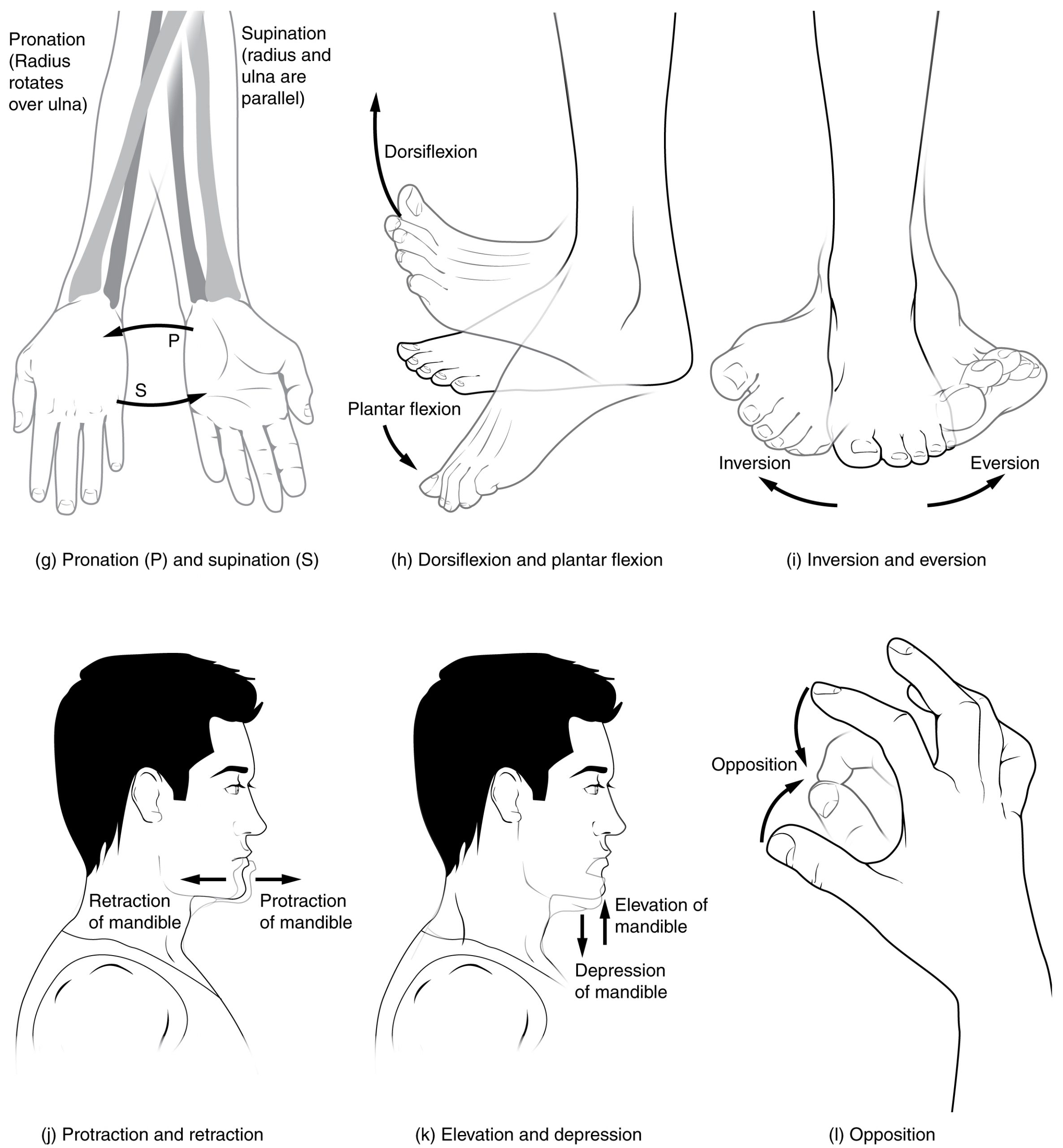

Joint Movements

Several movements may be performed by synovial joints. Abduction is the movement away from the midline of the body. Adduction is the movement toward the middle line of the body. Extension is the straightening of limbs (increase in angle) at a joint. Flexion is bending the limbs (reduction of angle) at a joint. Rotation is a circular movement around a fixed point. See Figures 13.9[23] and 13.10[24] for images of the types of movements of different joints in the body.

Joint Sounds

Sounds that occur as joints are moving are often referred to as crepitus. There are many different types of sounds that can occur as a joint moves, and patients may describe these sounds as popping, snapping, catching, clicking, crunching, cracking, crackling, creaking, grinding, grating, and clunking. There are several potential causes of these noises such as bursting of tiny bubbles in the synovial fluid, snapping of ligaments, or a disease condition. While assessing joints, be aware that joint noises are common during activity and are usually painless and harmless, but if they are associated with an injury or are accompanied by pain or swelling, they should be reported to the health care provider for follow-up.[25]

View Physitutor’s YouTube video for a review of crepitus sounds:

Physitutor’s “Why Your Knees Crack | Joint Crepitations[26]

- “701 Axial Skeleton-01.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/preface ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “1105 Anterior and Posterior Views of Muscles.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “1025 Atrophy.png” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/10-6-exercise-and-muscle-performance. ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2020. Muscle atrophy; [updated 2020, Sep 16; cited 2020, Sep 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003188.htm ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “907_Synovial_Joints.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “909 Types of Synovial Joints.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “914 Shoulder Joint.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “916 Hip Joint.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “917 Knee Joint.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Body Movements I.jpg” by Tonye Ogele CNX is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “Body Movements II.jpg” by Tonye Ogele CNX is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Song, S. J., Park, C. H., Liang, H., & Kim, S. J. (2018). Noise around the knee. Clinics in Orthopedic Surgery, 10(1), 1-8. https://dx.doi.org/10.4055%2Fcios.2018.10.1.1 ↵

- Physitutors. (2017, March 25). Why your knees crack | Joint crepitations. [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/NQOZZgh5z8I ↵

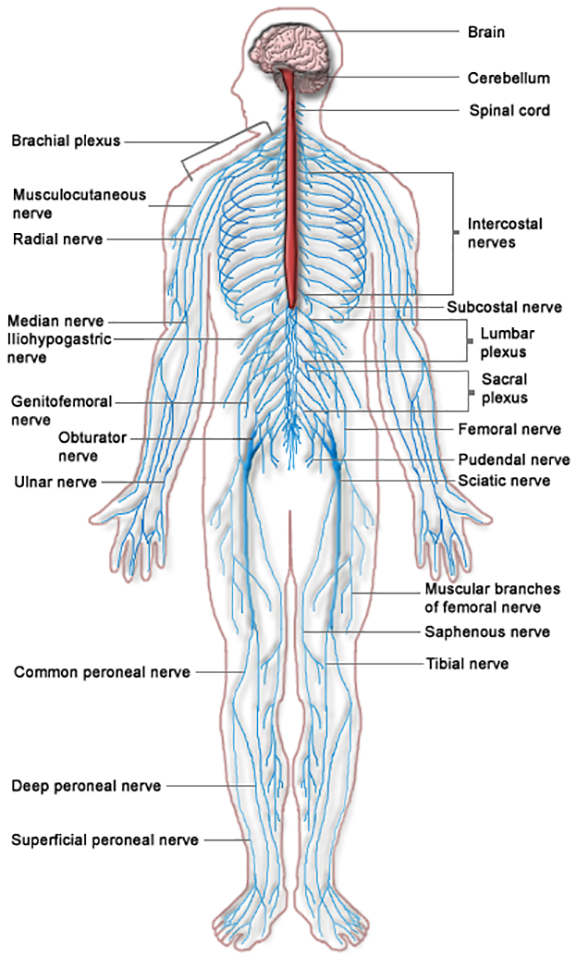

When completing a neurological assessment, it is important to understand the functions performed by different parts of the nervous system while analyzing findings. For example, damage to specific areas of the brain, such as that caused by a head injury or cerebrovascular accidents (i.e., strokes), can cause specific deficits in speech, facial movements, or use of the extremities. Damage to the spinal cord, such as that caused by a motor vehicle accident or diving accident, will cause specific motor and sensory deficits according to the level where the spinal cord was damaged.

The nervous system is divided into two parts, the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system. See Figure 6.1[1]for an image of the entire nervous system. The central nervous system (CNS) includes the brain and the spinal cord. The brain can be described as the interpretation center, and the spinal cord can be described as the transmission pathway. The peripheral nervous system (PNS) consists of the neurological system outside of the brain and spinal cord, including the cranial nerves that branch out from the brain and the spinal nerves that branch out from the spinal cord. The peripheral nervous system can be described as the communication network between the brain and the body parts. Both parts of the nervous system must work correctly for healthy body functioning.

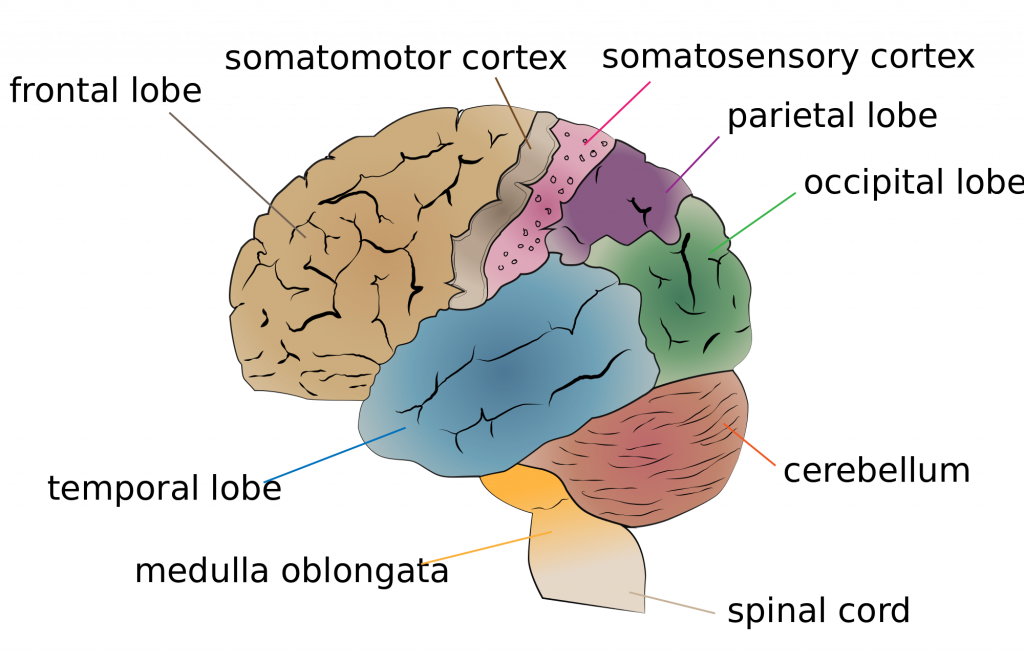

Central Nervous System

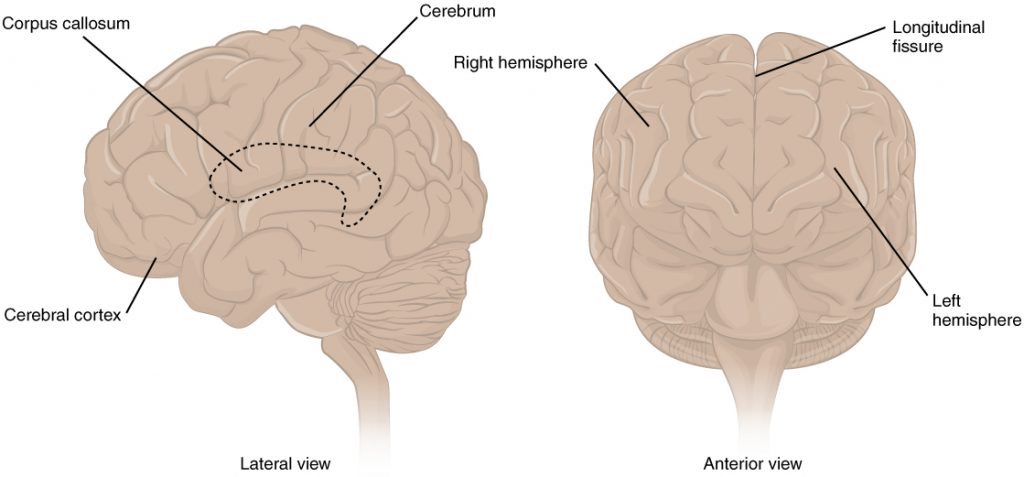

There major regions of the brain are the cerebrum and cerebral cortex, the diencephalon, the brain stem, and the cerebellum. See Figure 6.2[2] for an illustration of the cerebellum and the lobes of the cerebrum.

Cerebrum and Cerebral Cortex

The largest portion of our brain is the cerebrum. The cerebrum is covered by a wrinkled outer layer of gray matter called the cerebral cortex. See Figure 6.3[3] for an image of the cerebral cortex. The cerebral cortex is responsible for the higher functions of the nervous system such as memory, emotion, and consciousness. The corpus callosum is the major pathway of communication between the right and left hemispheres of the cerebral cortex. The cerebral cortex is further divided into four lobes named the frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal lobes.[4] Each lobe has specific functions.

Frontal Lobe

The frontal lobe is associated with movement because it contains neurons that instruct cells in the spinal cord to move skeletal muscles. The anterior portion of the frontal lobe is called the prefrontal lobe, and it provides cognitive functions such as planning and problem-solving that are the basis of our personality, short-term memory, and consciousness. Broca’s area is also located in the frontal lobe and is responsible for the production of language and controlling movements responsible for speech.[5]

Parietal Lobe

The parietal lobe processes general sensations from the body. All of the tactile senses are processed in this area, including touch, pressure, tickle, pain, itch, and vibration, as well as general senses of the body, such as proprioception (the sense of body position) and kinesthesia (the sense of movement).[6]

Temporal Lobe

The temporal lobe processes auditory information and is involved with language comprehension and production. Wernicke's area and Broca's area are located in the temporal lobe. Wernicke's area is involved in the comprehension of written and spoken language, and Broca's area is involved in the production of language. Because regions of the temporal lobe are part of the limbic system, memory is also an important function associated with the temporal lobe.[7] The limbic system is involved with our behavioral and emotional responses needed for survival, such as feeding, reproduction, and the fight - or - flight responses.

Occipital Lobe

The occipital lobe primarily processes visual information.[8]

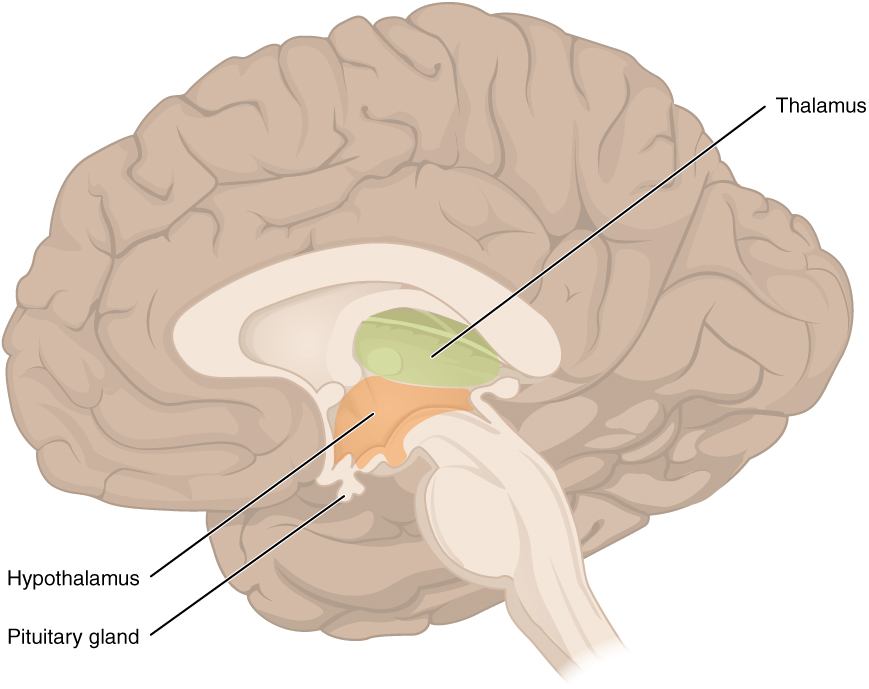

Diencephalon

Information from the rest of the central and peripheral nervous system is sent to the cerebrum through the diencephalon, with the exception of the olfactory nerve that connects directly to the cerebrum.[9] See Figure 6.4[10] for an illustration of the diencephalon deep within the cerebrum. The diencephalon contains the hypothalamus and the thalamus.

The hypothalamus helps regulate homeostasis such as body temperature, thirst, hunger, and sleep. The hypothalamus is also the executive region in charge of the autonomic nervous system and the endocrine system through its regulation of the anterior pituitary gland. Other parts of the hypothalamus are involved in memory and emotion as part of the limbic system.[11]

The thalamus relays sensory information and motor information in collaboration with the cerebellum. The thalamus does not just pass the information on, but it also processes and prioritizes that information. For example, the portion of the thalamus that receives visual information will influence what visual stimuli are considered important enough to receive further attention from the brain.[12]

Brain Stem

The brain stem is composed of the pons and the medulla. The pons and the medulla regulate several crucial autonomic functions in the body, including involuntary functions in the cardiovascular and respiratory systems, vasodilation, and reflexes like vomiting, coughing, sneezing, and swallowing. Cranial nerves also connect to the brain through the brain stem and provide sensory input and motor output.[13]

Cerebellum

The cerebellum is located in the posterior part of the brain behind the brain stem and is responsible for fine motor movements and coordination. For example, when the motor neurons in the frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex send a command down the spinal cord to initiate walking, a copy of that instruction is also sent to the cerebellum. Sensory feedback from the muscles and joints, proprioceptive information about the movements of walking, and sensations of balance are sent back to the cerebellum. If the person becomes unbalanced while walking because the ground is uneven, the cerebellum sends out a corrective command to compensate for the difference between the original cerebral cortex command and the sensory feedback.[14]

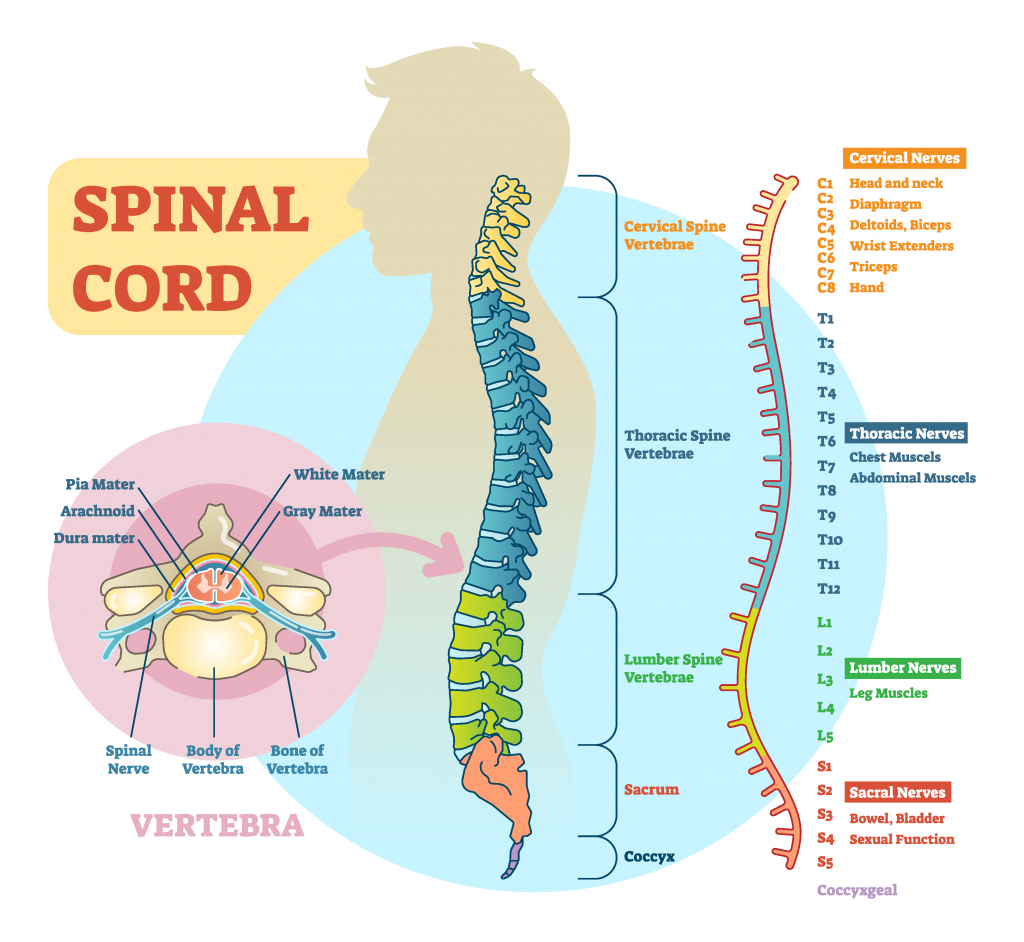

Spinal Cord

The spinal cord is a continuation of the brain stem that transmits sensory and motor impulses. The length of the spinal cord is divided into regions that correspond to the level at which spinal nerves pass through the vertebrae. Immediately adjacent to the brain stem is the cervical region, followed by the thoracic, the lumbar, and finally the sacral region.[15] The spinal nerves in each of these regions innervate specific parts of the body. See more information under the “Spinal Nerves” section.

Review the anatomy of the brain using following supplementary video.

Video Review for Anatomy of the Brain[16]

Peripheral Nervous System

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) consists of cranial nerves and spinal nerves that exist outside of the brain, spinal cord, and autonomic nervous system. The main function of the PNS is to connect the limbs and organs to the central nervous system (CNS). Sensory information from the body enters the CNS through cranial and spinal nerves. Cranial nerves are connected directly to the brain, whereas spinal nerves are connected to the brain via the spinal cord.

Peripheral nerves are classified as sensory nerves, motor nerves, or a combination of both. Sensory nerves carry impulses from the body to the brain for processing. Motor nerves transmit motor signals from the brain to the muscles to cause movement.

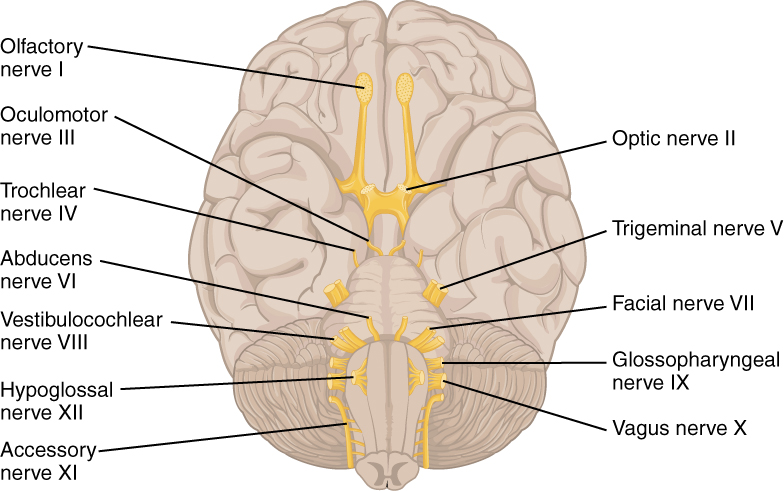

Cranial Nerves

Cranial nerves are directly connected from the periphery to the brain. They are primarily responsible for the sensory and motor functions of the head and neck. There are twelve cranial nerves that are designated by Roman numerals I through XII. See Figure 6.5[17] for an image of cranial nerves. Three cranial nerves are strictly sensory nerves; five are strictly motor nerves; and the remaining four are mixed nerves.[18] A traditional mnemonic for memorizing the names of the cranial nerves is “On Old Olympus Towering Tops A Finn And German Viewed Some Hops,” in which the initial letter of each word corresponds to the initial letter in the name of each nerve.

- The olfactory nerve is responsible for the sense of smell.

- The optic nerve is responsible for the sense of vision.

- The oculomotor nerve regulates eye movements by controlling four of the extraocular muscles, lifting the upper eyelid when the eyes point up and for constricting the pupils.

- The trochlear nerve and the abducens nerve are both responsible for eye movement, but do so by controlling different extraocular muscles.

- The trigeminal nerve regulates skin sensations of the face and controls the muscles used for chewing.

- The facial nerve is responsible for the muscles involved in facial expressions, as well as part of the sense of taste and the production of saliva.

- The accessory nerve controls movements of the neck.

- The vestibulocochlear nerve manages hearing and balance.

- The glossopharyngeal nerve regulates the controlling muscles in the oral cavity and upper throat, as well as part of the sense of taste and the production of saliva.

- The vagus nerve is responsible for contributing to homeostatic control of the organs of the thoracic and upper abdominal cavities.

- The spinal accessory nerve controls the muscles of the neck, along with cervical spinal nerves.

- The hypoglossal nerve manages the muscles of the lower throat and tongue.[19] Methods for assessing each of these nerves are described in the “Assessing Cranial Nerves” section.

Video Review of Cranial Nerves[20]

Spinal Nerves

There are 31 spinal nerves that are named based on the level of the spinal cord where they emerge. See Figure 6.6[21] for an illustration of spinal nerves. There are eight pairs of cervical nerves designated C1 to C8, twelve thoracic nerves designated T1 to T12, five pairs of lumbar nerves designated L1 to L5, five pairs of sacral nerves designated S1 to S5, and one pair of coccygeal nerves. All spinal nerves are combined sensory and motor nerves. Spinal nerves extend outward from the vertebral column to innervate the periphery while also transmitting sensory information back to the CNS.[22]

Functions of Spinal Nerves

Each spinal nerve innervates a specific region of the body:

- C1 provides motor innervation to muscles at the base of the skull.[23]

- C2 and C3 provide both sensory and motor control to the back of the head and behind the ears.[24]

- The phrenic nerve arises from nerve roots C3, C4, and C5. This is a vital nerve because it innervates the diaphragm to enable breathing. If a patient’s spinal cord is transected above C3 from an injury, then spontaneous breathing is not possible.[25]

- C5 through C8 and T1 combine to form the brachial plexus, a tangled array of nerves that serve the upper limbs and upper back.[26]

- The lumbar plexus arises from L1-L5 and innervates the pelvic region and the anterior leg.[27]

- The sacral plexus comes from the lower lumbar nerves L4 and L5 and the sacral nerves S1 to S4. The most significant systemic nerve to come from this plexus is the sciatic nerve. The sciatic nerve is associated with the painful medical condition sciatica, which is back and leg pain as a result of compression or irritation of the sciatic nerve.[28]

Functions of the Nervous System

The nervous system receives information about the environment around us (sensation) and generates responses to that information (motor responses). The process of integration combines sensory perceptions and higher cognitive functions such as memories, learning, and emotion while producing a response.

Sensation

Sensation is defined as receiving information about the environment. The major senses are taste, smell, touch, sight, and hearing. Additional sensory stimuli are also provided from inside the body, such as the stretch of an organ wall or the concentration of certain ions in the blood.[29]

Response

The nervous system produces a response based on the stimuli perceived by sensory nerves. For example, withdrawing a hand from a hot stove is an example of a response to a painfully hot stimulus. Responses can be classified by those that are voluntary (such as contraction of a skeletal muscle) and those that are involuntary (such as contraction of smooth muscle in the intestine). Voluntary responses are governed by the somatic nervous system, and involuntary responses are governed by the autonomic nervous system.[30]

Integration

Integration occurs when stimuli received by sensory nerves are communicated to the nervous system and the information is processed, leading to the generation of a conscious response. Consider this example of sensory integration. A batter in a baseball game does not automatically swing when they see the baseball thrown to them by the pitcher. First, the trajectory of the ball and its speed will need to be considered before creating the motor response of a swing. Then, integration will occur as the batter generates a conscious decision of whether to swing or not. Perhaps the count is three balls and one strike, and the batter decides to let this pitch go by in the hope of getting a walk to first base. Perhaps the batter is afraid to strike out and doesn’t swing, or maybe the batter learned the pitcher’s nonverbal cues the previous time at bat and is confident to take a swing at an anticipated fast ball. All of these considerations are included as part of the batter’s integration response and the higher level functioning that occurs in the cerebral cortex.[31]

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the '"Answer Key'" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

1. A male client has an impairment of cranial nerve II. Specific to this impairment, the nurse would plan to do which of the following to ensure client safety?

- Use loud a tone when speaking to the client

- Test the temperature of the shower water

- Check the temperature of the food prior to eating

- Remove obstacles when ambulating

2. The nurse is performing a mental status examination on a client with confusion. This test assesses which of the following?

- Cerebral function

- Cerebellar function

- Sensory function

- Intellectual function

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities'" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

1. You are working as a triage nurse in a primary care clinic. You just received a phone call from a young woman who is complaining of significant discomfort related to newly diagnosed strep throat. What instructions can you provide to her to aid in symptom management in order to alleviate discomfort?

2. You are assessing a patient's head and neck and note the following findings. Which should be reported to the health care provider?

- Tongue is midline

- White patches noted on both tonsils

- Uvula raises when patient says "Ahhh"

- Speech is slurred

- Thyroid enlarged

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the '"Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

A thorough assessment of the heart provides valuable information about the function of a patient’s cardiovascular system. Understanding how to properly assess the cardiovascular system and identifying both normal and abnormal assessment findings will allow the nurse to provide quality, safe care to the patient.

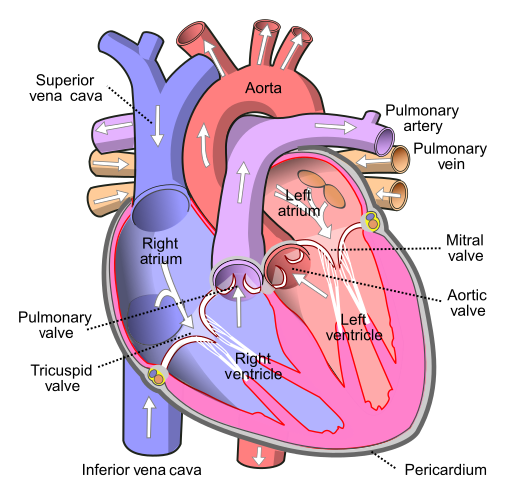

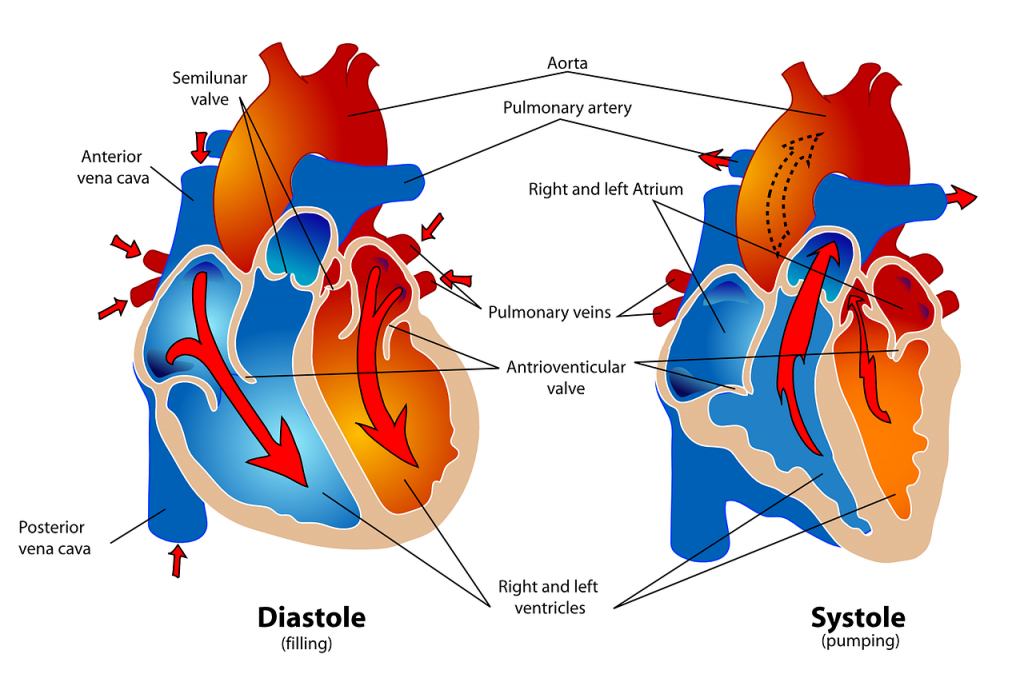

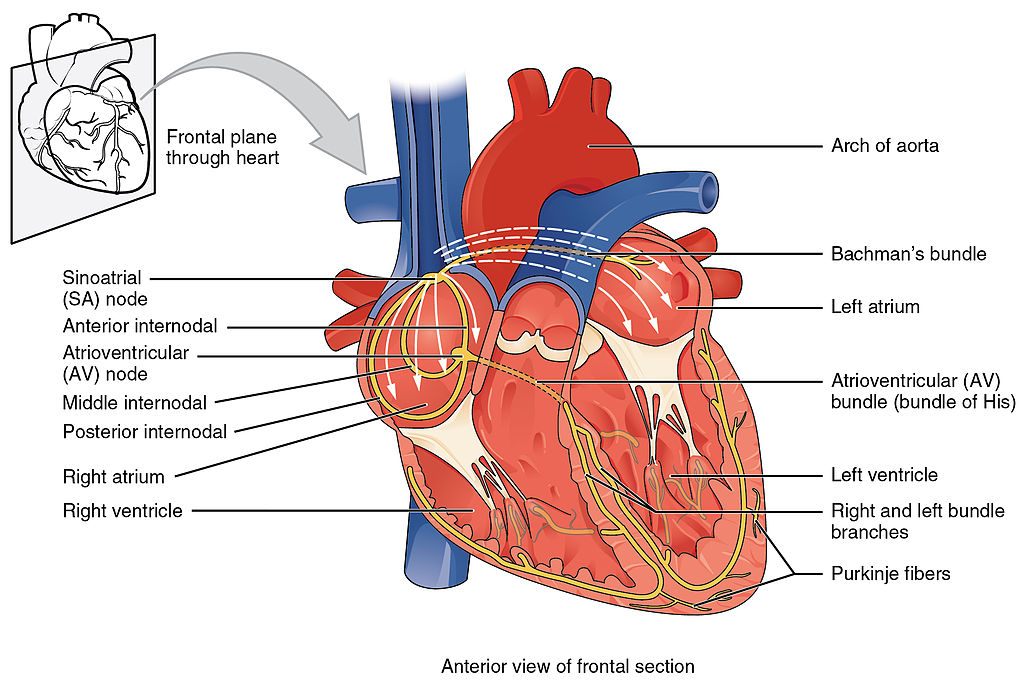

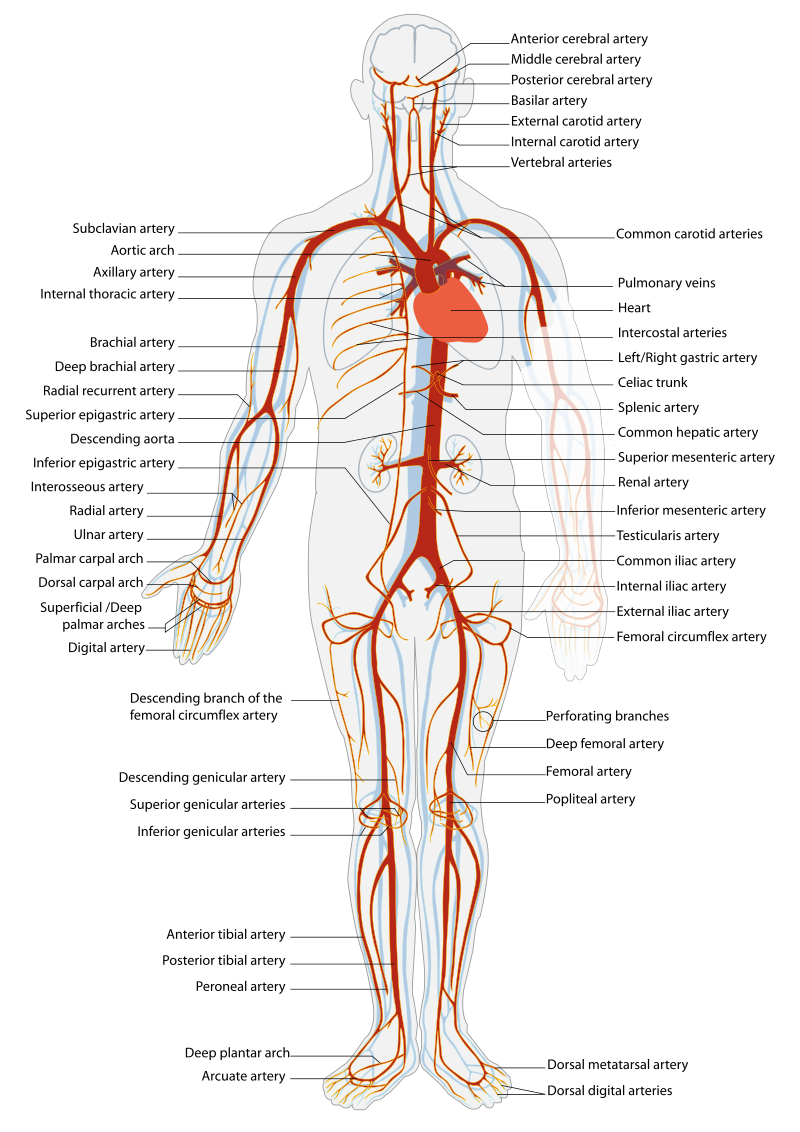

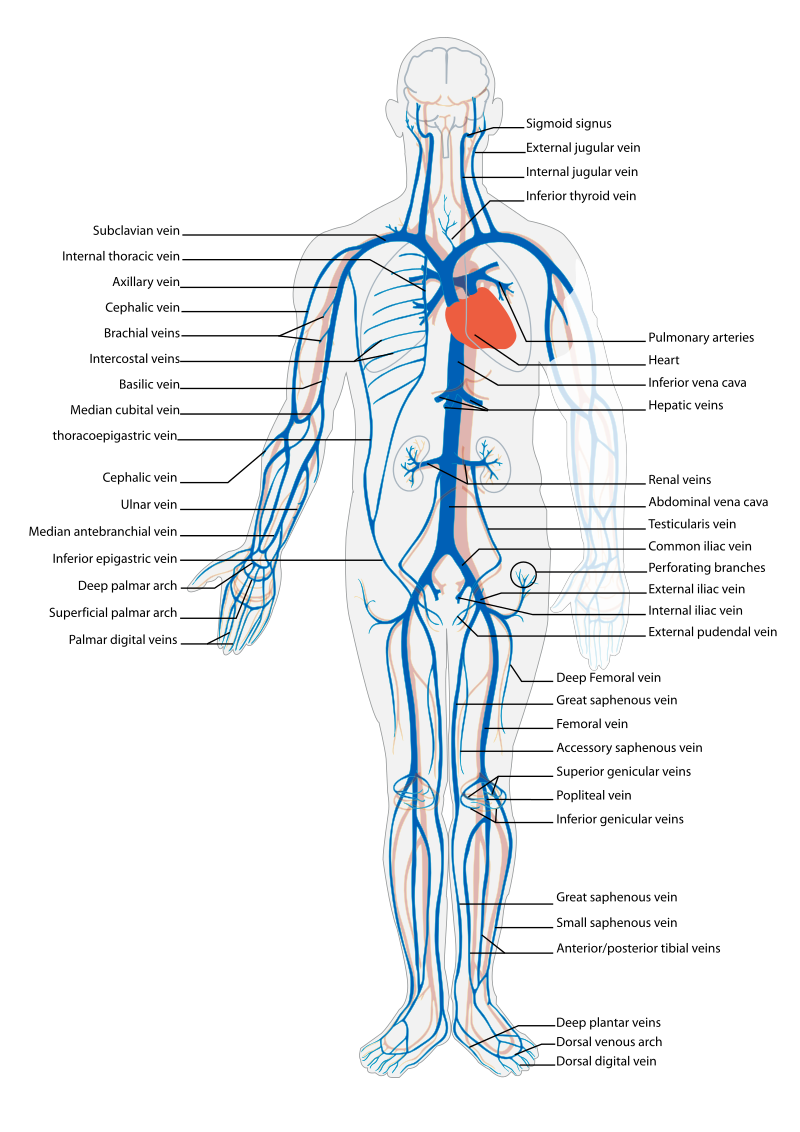

Before assessing a patient’s cardiovascular system, it is important to understand the various functions of the cardiovascular system. In addition to the information provided in the “Review of Cardiac Basics” section, the following images provide an overview of the cardiovascular system. Figure 9.1[32] provides an overview of the structure of the heart. Note the main cardiac structures are the atria, ventricles, and heart valves. Figure 9.2[33] demonstrates blood flow through the heart. Notice the flow of deoxygenated blood from the posterior and superior vena cava into the right atria and ventricle during diastole (indicated by blue coloring of these structures). The right ventricle then pumps deoxygenated blood to the lungs via the pulmonary artery during systole. At the same time, oxygenated blood from the lungs returns to the left atria and ventricle via the pulmonary veins during diastole (indicated by red coloring of these structures) and then is pumped out to the body via the aorta during systole. Figure 9.3[34] demonstrates the conduction system of the heart. This image depicts the conduction pathway through the heart as the tissue responds to electrical stimulation. Figure 9.4[35] illustrates the arteries of the circulatory system, and Figure 9.5[36] depicts the veins of the circulatory system. The purpose of these figures is to facilitate understanding of the electrical and mechanical function of the heart within the cardiovascular system.

Assessing the cardiovascular system includes performing several subjective and objective assessments. At times, assessment findings are modified according to life span considerations.

Subjective Assessment

The subjective assessment of the cardiovascular and peripheral vascular system is vital for uncovering signs of potential dysfunction. To complete the subjective cardiovascular assessment, the nurse begins with a focused interview. The focused interview explores past medical and family history, medications, cardiac risk factors, and reported symptoms. Symptoms related to the cardiovascular system include chest pain, peripheral edema, unexplained sudden weight gain, shortness of breath (dyspnea), irregular pulse rate or rhythm, dizziness, or poor peripheral circulation. Any new or worsening symptoms should be documented and reported to the health care provider.

Table 9.3a outlines questions used to assess symptoms related to the cardiovascular and peripheral vascular systems. Table 9.3b outlines questions used to assess medical history, medications, and risk factors related to the cardiovascular system. Information obtained from the interview process is used to tailor future patient education by the nurse.[37],[38],[39]

Table 9.3a Interview Questions for Cardiovascular and Peripheral Vascular Systems[40]

| Symptom | Question |

Follow-Up Safety Note: If findings indicate current severe symptoms suggestive of myocardial infarction or another critical condition, suspend the remaining cardiovascular assessment and obtain immediate assistance according to agency policy or call 911. |

|---|---|---|

| Chest Pain | Have you had any pain or pressure in your chest, neck, or arm? | Review how to assess a patient's chief complaint using the PQRSTU method in the "Health History" chapter.

|

| Shortness of Breath

(Dyspnea) |

Do you ever feel short of breath with activity?

Do you ever feel short of breath while sleeping? Do you feel short of breath when lying flat? |

What level of activity elicits shortness of breath?

How long does it take you to recover? Have you ever woken up from sleeping feeling suddenly short of breath How many pillows do you need to sleep, or do you sleep in a chair (orthopnea)? Has this recently changed? |

| Edema | Have you noticed swelling of your feet or ankles?

Have you noticed your rings, shoes, or clothing feel tight at the end of the day? Have you noticed any unexplained, sudden weight gain? Have you noticed any new abdominal fullness? |

Has this feeling of swelling or restriction gotten worse?

Is there anything that makes the swelling better (e.g., sitting with your feet elevated)? How much weight have you gained? Over what time period have you gained this weight? |

| Palpitations | Have you ever noticed your heart feels as if it is racing or “fluttering” in your chest?

Have you ever felt as if your heart “skips” a beat? |

Are you currently experiencing palpitations?

When did palpitations start? Have you previously been treated for palpitations? If so, what treatment did you receive? |

| Dizziness

(Syncope) |

Do you ever feel light-headed?

Do you ever feel dizzy? Have you ever fainted? |

Can you describe what happened?

Did you have any warning signs? Did this occur with position change? |

| Poor Peripheral Circulation | Do your hands or feet ever feel cold or look pale or bluish?

Do you have pain in your feet or lower legs when exercising? |

What, if anything, brings on these symptoms?

How much activity is needed to cause this pain? Is there anything, such as rest, that makes the pain better? |

| Calf Pain | Do you currently have any constant pain in your lower legs? | Can you point to the area of pain with one finger? |

Table 9.3b Interview Questions Exploring Cardiovascular Medical History, Medications, and Cardiac Risk Factors

| Topic | Questions |

|---|---|

| Medical History | Have you ever been diagnosed with any heart or circulation conditions, such as high blood pressure, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, high cholesterol, heart failure, or valve problems?

Have you had any procedures done to improve your heart function, such as ablation or stent placement? Have you ever had a heart attack or stroke? |

| Medications | Do you take any heart-related medications, herbs, or supplements to treat blood pressure, chest pain, high cholesterol, cardiac rhythm, fluid retention, or the prevention of clots? |

| Cardiac Risk Factors | Have your parents or siblings been diagnosed with any heart conditions?

Do you smoke or vape?

If you do not currently smoke, have you smoked in the past?

Are you physically active during the week?

What does a typical day look like in your diet?

Do you drink alcoholic drinks?

Would you say you experience stress in your life?

How many hours of sleep do you normally get each day?

|

Objective Assessment

The physical examination of the cardiovascular system involves the interpretation of vital signs, inspection, palpation, and auscultation of heart sounds as the nurse evaluates for sufficient perfusion and cardiac output.

Equipment needed for a cardiovascular assessment includes a stethoscope, penlight, centimeter ruler or tape measure, and sphygmomanometer.[41]

Evaluate Vital Signs and Level of Consciousness

Interpret the blood pressure and pulse readings to verify the patient is stable before proceeding with the physical exam. Assess the level of consciousness; the patient should be alert and cooperative.

Inspection

- Skin color to assess perfusion. Inspect the face, lips, and fingertips for cyanosis or pallor. Cyanosis is a bluish discoloration of the skin, lips, and nail beds and indicates decreased perfusion and oxygenation. Pallor is the loss of color, or paleness of the skin or mucous membranes, as a result of reduced blood flow, oxygenation, or decreased number of red blood cells. Patients with light skin tones should be pink in color. For those with darker skin tones, assess for pallor on the palms, conjunctiva, or inner aspect of the lower lip.

- Jugular Vein Distension (JVD). Inspect the neck for JVD that occurs when the increased pressure of the superior vena cava causes the jugular vein to bulge, making it most visible on the right side of a person's neck. JVD should not be present in the upright position or when the head of bed is at 30-45 degrees.

- Precordium for abnormalities. Inspect the chest area over the heart (also called precordium) for deformities, scars, or any abnormal pulsations the underlying cardiac chambers and great vessels may produce.

- Extremities:

- Upper Extremities: Inspect the fingers, arms, and hands bilaterally noting Color, Warmth, Movement, Sensation (CWMS). Alterations or bilateral inconsistency in CWMS may indicate underlying conditions or injury. Assess capillary refill by compressing the nail bed until it blanches and record the time taken for the color to return to the nail bed. Normal capillary refill is less than 3 seconds.[42]

- Lower Extremities: Inspect the toes, feet, and legs bilaterally, noting CWMS, capillary refill, and the presence of peripheral edema, superficial distended veins, and hair distribution. Document the location and size of any skin ulcers.

- Edema: Note any presence of edema. Peripheral edema is swelling that can be caused by infection, thrombosis, or venous insufficiency due to an accumulation of fluid in the tissues. (See Figure 9.6[43] for an image of pedal edema.)[44]

- Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT): A deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a blood clot that forms in a vein deep in the body. DVT requires emergency notification of the health care provider and immediate follow-up because of the risk of developing a life-threatening pulmonary embolism.[45] Inspect the lower extremities bilaterally. Assess for size, color, temperature, and for presence of pain in the calves. Unilateral warmth, redness, tenderness, swelling in the calf, or sudden onset of intense, sharp muscle pain that increases with dorsiflexion of the foot is an indication of a deep vein thrombosis (DVT).[46] See Figure 9.7[47] for an image of a DVT in the patient's right leg, indicated by unilateral redness and edema.

Auscultation

Heart Sounds

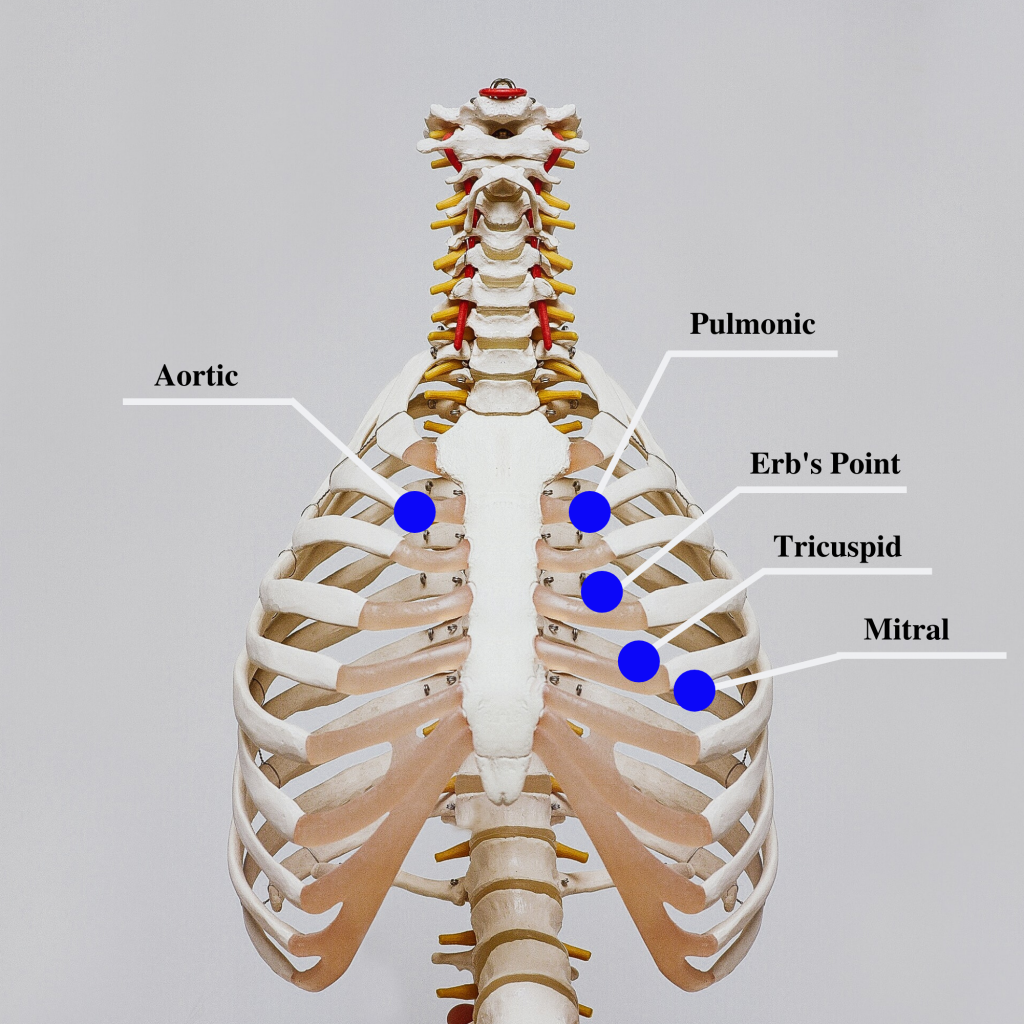

Auscultation is routinely performed over five specific areas of the heart to listen for corresponding valvular sounds. These auscultation sites are often referred to by the mnemonic “APE To Man,” referring to Aortic, Pulmonic, Erb’s point, Tricuspid, and Mitral areas (see Figure 9.8[48] for an illustration of cardiac auscultation areas). The aortic area is the second intercostal space to the right of the sternum. The pulmonary area is the second intercostal space to the left of the sternum. Erb's point is directly below the aortic area and located at the third intercostal space to the left of the sternum. The tricuspid (or parasternal) area is at the fourth intercostal space to the left of the sternum. The mitral (also called apical or left ventricular area) is the fifth intercostal space at the midclavicular line.

Auscultation usually begins at the aortic area (upper right sternal edge). Use the diaphragm of the stethoscope to carefully identify the S1 and S2 sounds. They will make a “lub-dub” sound. Note that when listening over the area of the aortic and pulmonic valves, the "dub" (S2) will sound louder than the "lub" (S2). Move the stethoscope sequentially to the pulmonic area (upper left sternal edge), Erb’s point (left third intercostal space at the sternal border), and tricuspid area (fourth intercostal space. When assessing the mitral area for female patients, it is often helpful to ask them to lift up their breast tissue so the stethoscope can be placed directly on the chest wall. Repeat this process with the bell of the stethoscope. The apical pulse should be counted over a 60-second period. For an adult, the heart rate should be between 60 and 100 with a regular rhythm to be considered within normal range. The apical pulse is an important assessment to obtain before the administration of many cardiac medications.

The first heart sound (S1) identifies the onset of systole, when the atrioventricular (AV) valves (mitral and tricuspid) close and the ventricles contract and eject the blood out of the heart. The second heart sound (S2) identifies the end of systole and the onset of diastole when the semilunar valves close, the AV valves open, and the ventricles fill with blood. When auscultating, it is important to identify the S1 ("lub") and S2 ("dub") sounds, evaluate the rate and rhythm of the heart, and listen for any extra heart sounds.

![]() Auscultating Heart Sounds

Auscultating Heart Sounds

- To effectively auscultate heart sounds, patient repositioning may be required. Ask the patient to lean forward if able, or position them to lie on their left side.

- It is common to hear lung sounds when auscultating the heart sounds. It may be helpful to ask the patient to briefly hold their breath if lung sounds impede adequate heart auscultation. Limit the holding of breath to 10 seconds or as tolerated by the patient.

- Environmental noise can cause difficulty in auscultating heart sounds. Removing environmental noise by turning down the television volume or shutting the door may be required for an accurate assessment.

- Patients may try to talk to you as you are assessing their heart sounds. It is often helpful to explain the procedure such as, “I am going to take a few minutes to listen carefully to the sounds of blood flow going through your heart. Please try not to speak while I am listening, so I can hear the sounds better.”

Extra Heart Sounds

Extra heart sounds include clicks, murmurs, S3 and S4 sounds, and pleural friction rubs. These extra sounds can be difficult for a novice to distinguish, so if you notice any new or different sounds, consult an advanced practitioner or notify the provider. A midsystolic click, associated with mitral valve prolapse, may be heard with the diaphragm at the apex or left lower sternal border.

A click may be followed by a murmur. A murmur is a blowing or whooshing sound that signifies turbulent blood flow often caused by a valvular defect. New murmurs not previously recorded should be immediately communicated to the health care provider. In the aortic area, listen for possible murmurs of aortic stenosis and aortic regurgitation with the diaphragm of the stethoscope. In the pulmonic area, listen for potential murmurs of pulmonic stenosis and pulmonary and aortic regurgitation. In the tricuspid area, at the fourth and fifth intercostal spaces along the left sternal border, listen for the potential murmurs of tricuspid regurgitation, tricuspid stenosis, or ventricular septal defect.

S3 and S4 sounds, if present, are often heard best by asking the patient to lie on their left side and listening over the apex with the bell of the stethoscope. An S3 sound, also called a ventricular gallop, occurs with fluid overload or heart failure when the ventricles are filling. It occurs after the S2 and sounds like “lub-dub-dah,” or a sound similar to a horse galloping. The S4 sound, also called atrial gallop, occurs immediately before the S1 and sounds like “ta-lub-dub.” An S4 sound can occur with decreased ventricular compliance or coronary artery disease.[49]

A pleural friction rub is caused by inflammation of the pericardium and sounds like sandpaper being rubbed together. It is best heard at the apex or left lower sternal border with the diaphragm as the patient sits up, leans forward, and holds their breath.

Carotid Sounds

The carotid artery may be auscultated for bruits. Bruits are a swishing sound due to turbulence in the blood vessel and may be heard due to atherosclerotic changes.

Palpation

Palpation is used to evaluate peripheral pulses, capillary refill, and for the presence of edema. When palpating these areas, also pay attention to the temperature and moisture of the skin.

Pulses

Compare the rate, rhythm, and quality of arterial pulses bilaterally, including the carotid, radial, brachial, posterior tibialis, and dorsalis pedis pulses. Review additional information about obtaining pulses in the "General Survey" chapter. Bilateral comparison for all pulses (except the carotid) is important for determining subtle variations in pulse strength. Carotid pulses should be palpated on one side at a time to avoid decreasing perfusion of the brain. The posterior tibial artery is located just behind the medial malleolus. It can be palpated by scooping the patient's heel in your hand and wrapping your fingers around so that the tips come to rest on the appropriate area just below the medial malleolus. The dorsalis pedis artery is located just lateral to the extensor tendon of the big toe and can be identified by asking the patient to flex their toe while you provide resistance to this movement. Gently place the tips of your second, third, and fourth fingers adjacent to the tendon, and try to feel the pulse.

The quality of the pulse is graded on a scale of 0 to 3, with 0 being absent pulses, 1 being decreased pulses, 2 is within normal range, and 3 being increased (also referred to as "bounding”). If unable to palpate a pulse, additional assessment is needed. First, determine if this is a new or chronic finding. Second, if available, use a doppler ultrasound to determine the presence or absence of the pulse. Many agencies use doppler ultrasound to document if a nonpalpable pulse is present. If the pulse is not found, this could be a sign of an emergent condition requiring immediate follow-up and provider notification. See Figures 9.9[50] and 9.10[51] for images of assessing pedal pulses.

Capillary Refill

The capillary refill test is performed on the nail beds to monitor perfusion, the amount of blood flow to tissue. Pressure is applied to a fingernail or toenail until it pales, indicating that the blood has been forced from the tissue under the nail. This paleness is called blanching. Once the tissue has blanched, pressure is removed. Capillary refill time is defined as the time it takes for the color to return after pressure is removed. If there is sufficient blood flow to the area, a pink color should return within 2 to 3 seconds after the pressure is removed.[52]

Edema

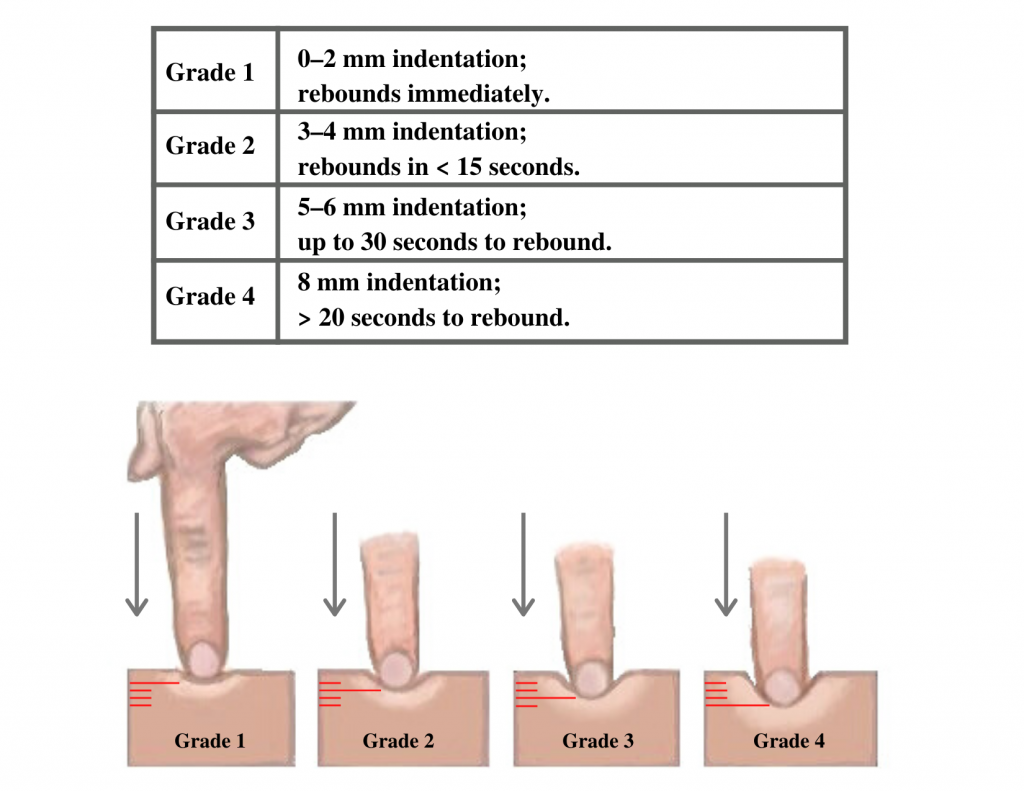

Edema occurs when one can visualize visible swelling caused by a buildup of fluid within the tissues. If edema is present on inspection, palpate the area to determine if the edema is pitting or nonpitting. Press on the skin to assess for indentation, ideally over a bony structure, such as the tibia. If no indentation occurs, it is referred to as nonpitting edema. If indentation occurs, it is referred to as pitting edema. See Figure 9.11[53] for images demonstrating pitting edema.

Note the depth of the indention and how long it takes for the skin to rebound back to its original position. The indentation and time required to rebound to the original position are graded on a scale from 1 to 4. Edema rated at 1+ indicates a barely detectable depression with immediate rebound, and 4+ indicates a deep depression with a time lapse of over 20 seconds required to rebound. See Figure 9.12[54] for an illustration of grading edema. Additionally, it is helpful to note edema may be difficult to observe in larger patients. It is also important to monitor for sudden changes in weight, which is considered a probable sign of fluid volume overload.

Heaves or Thrills

You may observe advanced practice nurses and other health care providers palpating the anterior chest wall to detect any abnormal pulsations the underlying cardiac chambers and great vessels may produce. Precordial movements should be evaluated at the apex (mitral area). It is best to examine the precordium with the patient supine because if the patient is turned on the left side, the apical region of the heart is displaced against the lateral chest wall, distorting the chest movements.[55] A heave or lift is a palpable lifting sensation under the sternum and anterior chest wall to the left of the sternum that suggests severe right ventricular hypertrophy. A thrill is a vibration felt on the skin of the precordium or over an area of turbulence, such as an arteriovenous fistula or graft.

Life Span Considerations

The cardiovascular assessment and expected findings should be modified according to common variations across the life span.

Infants and Children

A murmur may be heard in a newborn in the first few days of life until the ductus arteriosus closes.

When assessing the cardiovascular system in children, it is important to assess the apical pulse. Parameters for expected findings vary according to age group. After a child reaches adolescence, a radial pulse may be assessed. Table 9.3c outlines the expected apical pulse rate by age.

Table 9.3c Expected Apical Pulse by Age

| Age Group | Heart Rate |

|---|---|

| Preterm | 120-180 |

| Newborn (0 to 1 month) | 100-160 |

| Infant (1 to 12 months) | 80-140 |

| Toddler (1 to 3 years) | 80-130 |

| Preschool (3 to 5 years) | 80-110 |

| School Age (6 to 12 years) | 70-100 |

| Adolescents (13 to 18 years) | 60-90 |

Older Adults

In adults over age 65, irregular heart rhythms and extra sounds are more likely. An "irregularly irregular" rhythm suggests atrial fibrillation, and further investigation is required if this is a new finding. See the hyperlink in the box below for more information about atrial fibrillation.

Expected Versus Unexpected Findings

After completing a cardiovascular assessment, it is important for the nurse to use critical thinking to determine if any findings require follow-up. Depending on the urgency of the findings, follow-up can range from calling the health care provider to calling the rapid response team. Table 9.3d compares examples of expected findings, meaning those considered within normal limits, to unexpected findings, which require follow-up. Critical conditions are those that should be reported immediately and may require notification of a rapid response team.

Table 9.3d Expected Versus Unexpected Findings on Cardiac Assessment

| Assessment | Expected Findings | Unexpected Findings (Document and notify the provider if this is a new finding*) |

|---|---|---|

| Inspection | Apical impulse may or may not be visible | Scars not previously documented that could indicate prior cardiac surgeries

Heave or lift observed in the precordium Chest anatomy malformations |

| Palpation | Apical pulse felt over midclavicular fifth intercostal space | Apical pulse felt to the left of the midclavicular fifth intercostal space

Additional movements over precordium such as a heave, lift, or thrill |

| Auscultation | S1 and S2 heart sounds in a regular rhythm | New irregular heart rhythm

Extra heart sounds such as a murmur, S3, or S4 |

| *CRITICAL CONDITIONS to report immediately | Symptomatic tachycardia at rest (HR>100 bpm)

Symptomatic bradycardia (HR<60 bpm) New systolic blood pressure (<100 mmHg) Orthostatic blood pressure changes (see “Blood Pressure” chapter for more information) New irregular heart rhythm New extra heart sounds such as a murmur, S3, or S4 New abnormal cardiac rhythm changes Reported chest pain, calf pain, or worsening shortness of breath |

See Table 9.3e for a comparison of expected versus unexpected findings when assessing the peripheral vascular system.

Table 9.3e Expected Versus Unexpected Peripheral Vascular Assessment Findings

| Assessment | Expected Findings | Unexpected Findings (Document or notify provider if new finding*) |

|---|---|---|

| Inspection | Skin color uniform and appropriate for race bilaterally

Equal hair distribution on upper and lower extremities Absence of jugular vein distention (JVD) Absence of edema Sensation and movement of fingers and toes intact |

Cyanosis or pallor, indicating decreased perfusion

Decreased or unequal hair distribution Presence of jugular vein distention (JVD) in an upright position or when head of bed is 30-45 degrees New or worsening edema Rapid and unexplained weight gain Impaired movement or sensation of fingers and toes |

| Palpation | Skin warm and dry

Pulses present and equal bilaterally Absence of edema Capillary refill less than 2 seconds |

Skin cool, excessively warm, or diaphoretic

Absent, weak/thready, or bounding pulses New irregular pulse New or worsening edema Capillary refill greater than 2 seconds Unilateral warmth, redness, tenderness, or edema, indicating possible deep vein thrombosis (DVT) |

| Auscultation | Carotid pulse | Carotid bruit |

| *CRITICAL CONDITIONS to report immediately | Cyanosis

Absent pulse (and not heard using Doppler device) Capillary refill time greater than 3 seconds Unilateral redness, warmth, and edema, indicating a possible deep vein thrombosis (DVT) |

“Sternum_composition.png” by Anatomography is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.1 Japan

“Sternum_composition.png” by Anatomography is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.1 Japan

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

1. As you walk into your patient’s room, you notice the patient appears to be short of breath. Your patient states “I have been short of breath and tired for the past week.” Upon assessment of your patient, you notice JVD, labored breathing, lung sounds with crackles in the posterior bases, and +2 edema to the lower extremities bilaterally.

From your assessment findings, determine the most likely disease state that is being described.

- Hypertension

- Pulmonary Embolism

- Heart Failure

- Stroke

2. Your patient puts on the call light. You enter the room and notice the patient appears to be in distress. The patient states, “I cannot catch my breath and my heart feels like it is going to explode.” The patient's vital signs are T 98, P 148, BP 112/68, and pulse oximetry 88% on room air. You apply oxygen at 2 liters/minute via nasal cannula and notify the health care provider (HCP). The HCP orders a stat ECG. The patient's pulse oximetry increases to 94% with the oxygen, and the patient states, “I feel less short of breath but my heart is still racing.” Upon assessment of heart sounds, the apical pulse is 134 and irregular. The ECG results indicate atrial fibrillation.

What would be your next action?

- Leave the room and see your other patients.

- Stay with the patient and notify the HCP of the ECG results.

- Have the CNA stay with your patient as you take a break.

- Stay with the patient and wait for them to calm down.

With an understanding of the basic structures and primary functions of the respiratory system, the nurse collects subjective and objective data to perform a focused respiratory assessment.

Subjective Assessment

Collect data using interview questions, paying particular attention to what the patient is reporting. The interview should include questions regarding any current and past history of respiratory health conditions or illnesses, medications, and reported symptoms. Consider the patient’s age, gender, family history, race, culture, environmental factors, and current health practices when gathering subjective data. The information discovered during the interview process guides the physical exam and subsequent patient education. See Table 10.3a for sample interview questions to use during a focused respiratory assessment.[56]

Table 10.3a Interview Questions for Subjective Assessment of the Respiratory System

| Interview Questions | Follow-up |

|---|---|

| Have you ever been diagnosed with a respiratory condition, such as asthma, COPD, pneumonia, or allergies?

Do you use oxygen or peak flow meter? Do you use home respiratory equipment like CPAP, BiPAP, or nebulizer devices? |

Please describe the conditions and treatments. |

| Are you currently taking any medications, herbs, or supplements for respiratory concerns? | Please identify what you are taking and the purpose of each. |

| Have you had any feelings of breathlessness (dyspnea)? | Note: If the shortness of breath is severe or associated with chest pain, discontinue the interview and obtain emergency assistance.

Are you having any shortness of breath now? If yes, please rate the shortness of breath from 0-10 with "0" being none and "10" being severe? Does anything bring on the shortness of breath (such as activity, animals, food, or dust)? If activity causes the shortness of breath, how much exertion is required to bring on the shortness of breath? When did the shortness of breath start? Is the shortness of breath associated with chest pain or discomfort? How long does the shortness of breath last? What makes the shortness of breath go away? Is the shortness of breath related to a position, like lying down? Do you sleep in a recliner or upright in bed? Do you wake up at night feeling short of breath? How many pillows do you sleep on? How does the shortness of breath affect your daily activities? |

| Do you have a cough? | When you cough, do you bring up anything? What color is the phlegm?

Do you cough up any blood (hemoptysis)? Do you have any associated symptoms with the cough such as fever, chills, or night sweats? How long have you had the cough? Does anything bring on the cough (such as activity, dust, animals, or change in position)? What have you used to treat the cough? Has it been effective? |

| Do you smoke or vape? | What products do you smoke/vape? If cigarettes are smoked, how many packs a day do you smoke?

How long have you smoked/vaped? Have you ever tried to quit smoking/vaping? What strategies gave you the best success? Are you interested in quitting smoking/vaping? If the patient is ready to quit, the five successful interventions are the "5 A's": Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange. Ask - Identify and document smoking status for every patient at every visit. Advise - In a clear, strong, and personalized manner, urge every user to quit. Assess - Is the user willing to make a quitting attempt at this time? Assist - For the patient willing to make a quitting attempt, use counseling and pharmacotherapy to help them quit. Arrange - Schedule follow-up contact, in person or by telephone, preferably within the first week after the quit date.[57] |

Life Span Considerations

Depending on the age and capability of the child, subjective data may also need to be retrieved from a parent and/or legal guardian.

Pediatric

- Is your child up-to-date with recommended immunizations?

- Is your child experiencing any cold symptoms (such as runny nose, cough, or nasal congestion)?

- How is your child’s appetite? Is there any decrease or change recently in appetite or wet diapers?

- Does your child have any hospitalization history related to respiratory illness?

- Did your child have any history of frequent ear infections as an infant?

Older Adult

- Have you noticed a change in your breathing?

- Do you get short of breath with activities that you did not before?

- Can you describe your energy level? Is there any change from previous?

Objective Assessment

A focused respiratory objective assessment includes interpretation of vital signs; inspection of the patient’s breathing pattern, skin color, and respiratory status; palpation to identify abnormalities; and auscultation of lung sounds using a stethoscope. For more information regarding interpreting vital signs, see the “General Survey” chapter. The nurse must have an understanding of what is expected for the patient’s age, gender, development, race, culture, environmental factors, and current health condition to determine the meaning of the data that is being collected.

Evaluate Vital Signs

The vital signs may be taken by the nurse or delegated to unlicensed assistive personnel such as a nursing assistant or medical assistant. Evaluate the respiratory rate and pulse oximetry readings to verify the patient is stable before proceeding with the physical exam. The normal range of a respiratory rate for an adult is 12-20 breaths per minute at rest, and the normal range for oxygen saturation of the blood is 94–98% (SpO₂)[58] Bradypnea is less than 12 breaths per minute, and tachypnea is greater than 20 breaths per minute.

Inspection

Inspection during a focused respiratory assessment includes observation of level of consciousness, breathing rate, pattern and effort, skin color, chest configuration, and symmetry of expansion.

- Assess the level of consciousness. The patient should be alert and cooperative. Hypoxemia (low blood levels of oxygen) or hypercapnia (high blood levels of carbon dioxide) can cause a decreased level of consciousness, irritability, anxiousness, restlessness, or confusion.

- Obtain the respiratory rate over a full minute. The normal range for the respiratory rate of an adult is 12-20 breaths per minute.

- Observe the breathing pattern, including the rhythm, effort, and use of accessory muscles. Breathing effort should be nonlabored and in a regular rhythm. Observe the depth of respiration and note if the respiration is shallow or deep. Pursed-lip breathing, nasal flaring, audible breathing, intercostal retractions, anxiety, and use of accessory muscles are signs of respiratory difficulty. Inspiration should last half as long as expiration unless the patient is active, in which case the inspiration-expiration ratio increases to 1:1.

- Observe pattern of expiration and patient position. Patients who experience difficulty expelling air, such as those with emphysema, may have prolonged expiration cycles. Some patients may experience difficulty with breathing specifically when lying down. This symptom is known as orthopnea. Additionally, patients who are experiencing significant breathing difficulty may experience most relief while in a “tripod” position. This can be achieved by having the patient sit at the side of the bed with legs dangling toward the floor. The patient can then rest their arms on an overbed table to allow for maximum lung expansion. This position mimics the same position you might take at the end of running a race when you lean over and place your hands on your knees to “catch your breath.”

- Observe the patient’s color in their lips, face, hands, and feet. Patients with light skin tones should be pink in color. For those with darker skin tones, assess for pallor on the palms, conjunctivae, or inner aspect of the lower lip. Cyanosis is a bluish discoloration of the skin, lips, and nail beds, which may indicate decreased perfusion and oxygenation. Pallor is the loss of color, or paleness of the skin or mucous membranes and usually the result of reduced blood flow, oxygenation, or decreased number of red blood cells.

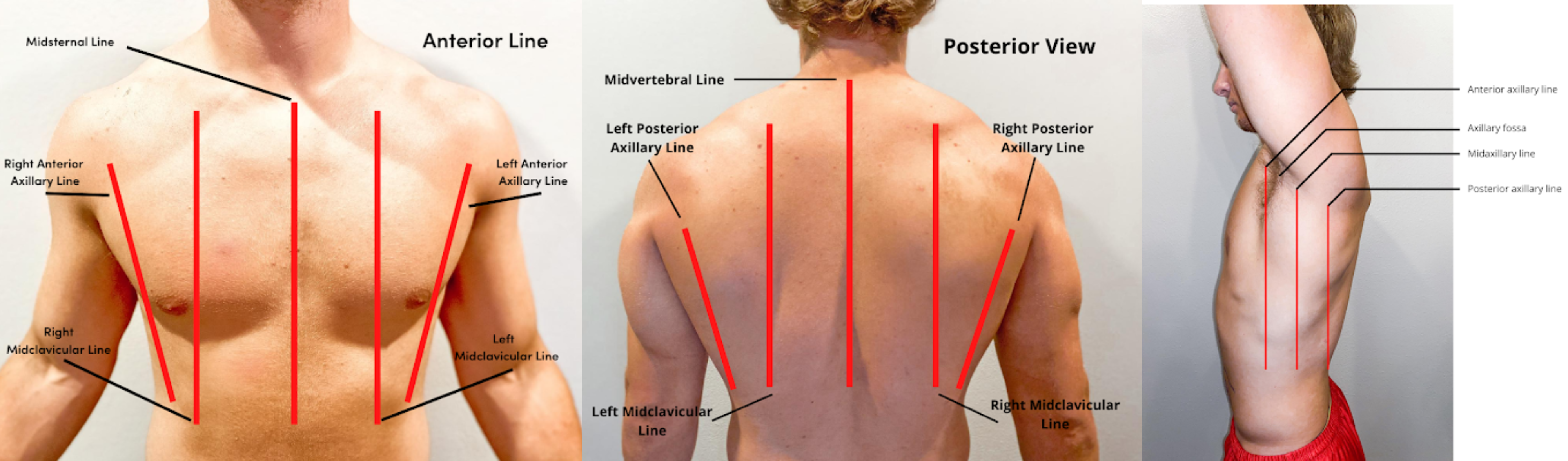

- Inspect the chest for symmetry and configuration. The trachea should be midline, and the clavicles should be symmetrical. See Figure 10.2[59] for visual landmarks when inspecting the thorax anteriorly, posteriorly, and laterally. Note the location of the ribs, sternum, clavicle, and scapula, as well as the underlying lobes of the lungs.

- Chest movement should be symmetrical on inspiration and expiration.

- Observe the anterior-posterior diameter of the patient’s chest and compare to the transverse diameter. The expected anteroposterior-transverse ratio should be 1:2. A patient with a 1:1 ratio is described as barrel-chested. This ratio is often seen in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease due to hyperinflation of the lungs. See Figure 10.3[60] for an image of a patient with a barrel chest.

- Older patients may have changes in their anatomy, such as kyphosis, an outward curvature of the spine.

- Inspect the fingers for clubbing if the patient has a history of chronic respiratory disease. Clubbing is a bulbous enlargement of the tips of the fingers due to chronic hypoxia. See Figure 10.4[61] for an image of clubbing.

Palpation

- Palpation of the chest may be performed to investigate for areas of abnormality related to injury or procedural complications. For example, if a patient has a chest tube or has recently had one removed, the nurse may palpate near the tube insertion site to assess for areas of air leak or crepitus. Crepitus feels like a popping or crackling sensation when the skin is palpated and is a sign of air trapped under the subcutaneous tissues. If palpating the chest, use light pressure with the fingertips to examine the anterior and posterior chest wall. Chest palpation may be performed to assess specifically for growths, masses, crepitus, pain, or tenderness.

- Confirm symmetric chest expansion by placing your hands on the anterior or posterior chest at the same level, with thumbs over the sternum anteriorly or the spine posteriorly. As the patient inhales, your thumbs should move apart symmetrically. Unequal expansion can occur with pneumonia, thoracic trauma, such as fractured ribs, or pneumothorax.

Auscultation

Using the diaphragm of the stethoscope, listen to the movement of air through the airways during inspiration and expiration. Instruct the patient to take deep breaths through their mouth. Listen through the entire respiratory cycle because different sounds may be heard on inspiration and expiration. As you move across the different lung fields, the sounds produced by airflow vary depending on the area you are auscultating because the size of the airways change.

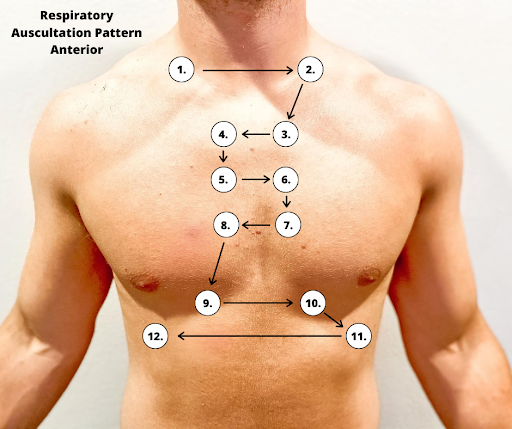

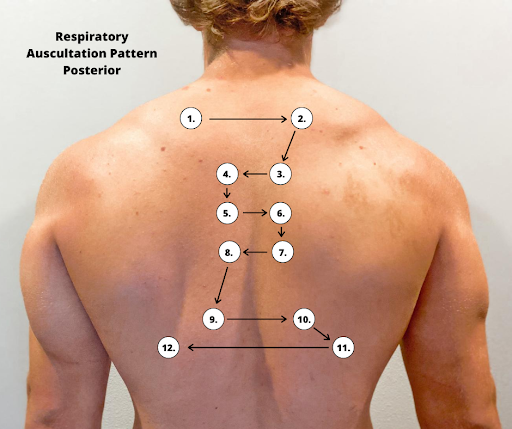

Correct placement of the stethoscope during auscultation of lung sounds is important to obtain a quality assessment. The stethoscope should not be performed over clothes or hair because these may create inaccurate sounds from friction. The best position to listen to lung sounds is with the patient sitting upright; however, if the patient is acutely ill or unable to sit upright, turn them side to side in a lying position. Avoid listening over bones, such as the scapulae or clavicles or over the female breasts to ensure you are hearing adequate sound transmission. Listen to sounds from side to side rather than down one side and then down the other side. This side-to-side pattern allows you to compare sounds in symmetrical lung fields. See Figures 10.5[62] and 10.6[63] for landmarks of stethoscope placement over the anterior and posterior chest wall.

Expected Breath Sounds

It is important upon auscultation to have awareness of expected breath sounds in various anatomical locations.

- Bronchial breath sounds are heard over the trachea and larynx and are high-pitched and loud.

- Bronchovesicular sounds are medium-pitched and heard over the major bronchi.

- Vesicular breath sounds are heard over the lung surfaces, are lower-pitched, and often described as soft, rustling sounds.

Adventitious Lung Sounds

Adventitious lung sounds are sounds heard in addition to normal breath sounds. They most often indicate an airway problem or disease, such as accumulation of mucus or fluids in the airways, obstruction, inflammation, or infection. These sounds include rales/crackles, rhonchi/wheezes, stridor, and pleural rub:

- Fine crackles, also called rales, are popping or crackling sounds heard on inspiration that occur in association with conditions that cause fluid to accumulate within the alveolar and interstitial spaces, such as heart failure or pneumonia. The sound is similar to that produced by rubbing strands of hair together close to your ear.

- Wheezes are whistling-type noises produced during expiration (and sometimes inspiration) when air is forced through airways narrowed by bronchoconstriction or associated mucosal edema. For example, patients with asthma commonly have wheezing.

- Stridor is heard only on inspiration. It is associated with mechanical obstruction at the level of the trachea/upper airway.

- Pleural rub may be heard on either inspiration or expiration and sounds like the rubbing together of leather. A pleural rub is heard when there is inflammation of the lung pleura, resulting in friction as the surfaces rub against each other.[64]

Life Span Considerations

Children

There are various respiratory assessment considerations that should be noted with assessment of children.

- The respiratory rate in children less than 12 months of age can range from 30-60 breaths per minute, depending on whether the infant is asleep or active.

- Infants have irregular or periodic newborn breathing in the first few weeks of life; therefore, it is important to count the respirations for a full minute. During this time, you may notice periods of apnea lasting up to 10 seconds. This is not abnormal unless the infant is showing other signs of distress. Signs of respiratory distress in infants and children include nasal flaring and sternal or intercostal retractions.

- Up to three months of age, infants are considered “obligate” nose-breathers, meaning their breathing is primarily through the nose.

- The anteroposterior-transverse ratio is typically 1:1 until the thoracic muscles are fully developed around six years of age.

Older Adults

As the adult person ages, the cartilage and muscle support of the thorax becomes weakened and less flexible, resulting in a decrease in chest expansion. Older adults may also have weakened respiratory muscles, and breathing may become more shallow. The anteroposterior-transverse ratio may be 1:1 if there is significant curvature of the spine (kyphosis).

Percussion

Percussion is an advanced respiratory assessment technique that is used by advanced practice nurses and other health care providers to gather additional data in the underlying lung tissue. By striking the fingers of one hand over the fingers of the other hand, a sound is produced over the lung fields that helps determine if fluid is present. Dull sounds are heard with high-density areas, such as pneumonia or atelectasis, whereas clear, low-pitched, hollow sounds are heard in normal lung tissue.

![]()

- Because infants breathe primarily through the nose, nasal congestion can limit the amount of air getting into the lungs.

- Attempt to assess an infant’s respiratory rate while the infant is at rest and content rather than when the infant is crying. Counting respirations by observing abdominal breathing movements may be easier for the novice nurse than counting breath sounds, as it can be difficult to differentiate lung and heart sounds when auscultating newborns.

- Auscultation of lungs during crying is not a problem. It will enhance breath sounds.

- The older patient may have a weakening of muscles that support respiration and breathing. Therefore, the patient may report tiring easily during the assessment when taking deep breaths. Break up the assessment by listening to the anterior lung sounds and then the heart sounds and allowing the patient to rest before listening to the posterior lung sounds.

- Patients with end-stage COPD may have diminished lung sounds due to decreased air movement. This abnormal assessment finding may be the patient’s baseline or normal and might also include wheezes and fine crackles as a result of chronic excess secretions and/or bronchoconstriction.[65],[66]

Expected Versus Unexpected Findings

See Table 10.3b for a comparison of expected versus unexpected findings when assessing the respiratory system.[67]

Table 10.3b Expected Versus Unexpected Respiratory Assessment Findings

| Assessment | Expected Findings | Unexpected Findings (Document and notify provider if a new finding*) |

|---|---|---|

| Inspection | Work of breathing effortless

Regular breathing pattern Respiratory rate within normal range for age Chest expansion symmetrical Absence of cyanosis or pallor Absence of accessory muscle use, retractions, and/or nasal flaring Anteroposterior: transverse diameter ratio 1:2 |

Labored breathing

Irregular rhythm Increased or decreased respiratory rate Accessory muscle use, pursed-lip breathing, nasal flaring (infants), and/or retractions Presence of cyanosis or pallor Asymmetrical chest expansion Clubbing of fingernails |

| Palpation | No pain or tenderness with palpation. Skin warm and dry; no crepitus or masses | Pain or tenderness with palpation, crepitus, palpable masses, or lumps |

| Percussion | Clear, low-pitched, hollow sound in normal lung tissue | Dull sounds heard with high-density areas, such as pneumonia or atelectasis |

| Auscultation | Bronchovesicular and vesicular sounds heard over appropriate areas

Absence of adventitious lung sounds |

Diminished lung sounds

Adventitious lung sounds, such as fine crackles/rales, wheezing, stridor, or pleural rub |

| *CRITICAL CONDITIONS to report immediately | Decreased oxygen saturation <92%[68]

Pain Worsening dyspnea Decreased level of consciousness, restlessness, anxiousness, and/or irritability |

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

1. An elderly client is admitted to the medical floor with increased shortness of breath, new productive cough, and low-grade fever. The nurse begins the physical examination of the respiratory system.

What is the best position for the client to assume for the physical exam?

- Supine

- Sitting upright

- Semi-Fowlers

- Left-lateral

2. During the course of the preceding patient's physical exam, auscultation of the lungs reveals rhonchi in the upper airways and coarse crackles in the right lower base. The nurse knows that rhonchi and crackles may indicate _______ or __________ in the airways.

3. A client has pneumonia, which is currently being treated with antibiotics, and reports feeling better since being hospitalized. The nurse assesses the client’s oxygen saturation using a pulse oximeter by placing the probe on the client’s finger. The reading is 89%.

Which of the following actions should the nurse perform first?

- Assess the pulse oximeter probe site to ensure an accurate reading.

- Administer oxygen and monitor the pulse oximetry until it reaches 95 percent.

- Raise the head of the bed and ask the client to take several deep breaths.

- Contact the provider and recommend prescribing a chest X-ray.

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the '"Answer Key'" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

1. Your patient turns on their call light. Upon entering your patient’s room, they say they are short of breath. Prioritize your actions from first to sixth.

Institute actions to improve oxygenation

Apply oxygen as ordered

Reassess pulse oximetry

Teach oxygen safety

Assess lung sounds

Assess pulse oximetry

| Priority | Actions |

|---|---|

| First | |

| Second | |

| Third | |

| Four | |

| Fifth | |

| Sixth |

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the '"Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

The nurse is performing a daily assessment on a patient who had hip surgery a few days ago. The patient reports she has not had a bowel movement since prior to admission three days ago. The nurse forms a hypothesis that the patient is constipated.

1. What subjective data should the nurse plan to obtain during the assessment to investigate “cues” regarding the potential hypothesis of constipation?

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Lactose intolerance

- Bloating

2. What objective data should the nurse plan to obtain during the assessment to investigate “cues” regarding the potential hypothesis of constipation?

- Bowel sounds

- Skin integrity

- Abdominal pulsations

- Bladder distention

3. The nurse discovers the following findings during the assessment. Which should be reported to the provider?

- The patient’s abdomen appears flat and symmetric.

- There are hypoactive bowel sounds in all quadrants.

- Firmness is palpated in left lower quadrant.

- There is a scar from a previous appendectomy.

4. The nurse calls the provider and reports the assessment findings supporting the hypothesis of constipation. A new order for Milk of Magnesia 30 mL PO is obtained and the medication is administered. A few hours later, the patient has a large bowel movement. Write a focused DAR or SOAP note documenting the patient’s constipation status.

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

1. During a musculoskeletal assessment, the nurse has the patient simultaneously resist against exerted force with both upper extremities. The nurse knows this it is important to perform this assessment on both extremities simultaneously for what reason?

- It measures muscle strength symmetry.

- It provides a more accurate reading.

- It involves more muscle use.

- It decreases assessment time.

2. The nurse is testing upper body strength on an adolescent. The test indicates full ROM against gravity and full resistance. How does the nurse document these assessment findings according to the muscle strength scale?

- 4 out of 5

- 3 out of 5

- 5 out of 5

- 1 out of 5

3. A young adult presents to the urgent care with a right knee injury. The injury occurred during a basketball game. The nurse begins to perform a musculoskeletal assessment. What is the first step of the assessment?

- Palpation

- Inspection

- Percussion

- Auscultation