10.3 Respiratory Assessment

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

With an understanding of the basic structures and primary functions of the respiratory system, the nurse collects subjective and objective data to perform a focused respiratory assessment.

Subjective Assessment

Collect data using interview questions, paying particular attention to what the patient is reporting. The interview should include questions regarding any current and past history of respiratory health conditions or illnesses, medications, and reported symptoms. Consider the patient’s age, gender, family history, race, culture, environmental factors, and current health practices when gathering subjective data. The information discovered during the interview process guides the physical exam and subsequent patient education. See Table 10.3a for sample interview questions to use during a focused respiratory assessment.[1]

Table 10.3a Interview Questions for Subjective Assessment of the Respiratory System

| Interview Questions | Follow-up |

|---|---|

| Have you ever been diagnosed with a respiratory condition, such as asthma, COPD, pneumonia, or allergies?

Do you use oxygen or peak flow meter? Do you use home respiratory equipment like CPAP, BiPAP, or nebulizer devices? |

Please describe the conditions and treatments. |

| Are you currently taking any medications, herbs, or supplements for respiratory concerns? | Please identify what you are taking and the purpose of each. |

| Have you had any feelings of breathlessness (dyspnea)? | Note: If the shortness of breath is severe or associated with chest pain, discontinue the interview and obtain emergency assistance.

Are you having any shortness of breath now? If yes, please rate the shortness of breath from 0-10 with “0” being none and “10” being severe? Does anything bring on the shortness of breath (such as activity, animals, food, or dust)? If activity causes the shortness of breath, how much exertion is required to bring on the shortness of breath? When did the shortness of breath start? Is the shortness of breath associated with chest pain or discomfort? How long does the shortness of breath last? What makes the shortness of breath go away? Is the shortness of breath related to a position, like lying down? Do you sleep in a recliner or upright in bed? Do you wake up at night feeling short of breath? How many pillows do you sleep on? How does the shortness of breath affect your daily activities? |

| Do you have a cough? | When you cough, do you bring up anything? What color is the phlegm?

Do you cough up any blood (hemoptysis)? Do you have any associated symptoms with the cough such as fever, chills, or night sweats? How long have you had the cough? Does anything bring on the cough (such as activity, dust, animals, or change in position)? What have you used to treat the cough? Has it been effective? |

| Do you smoke or vape? | What products do you smoke/vape? If cigarettes are smoked, how many packs a day do you smoke?

How long have you smoked/vaped? Have you ever tried to quit smoking/vaping? What strategies gave you the best success? Are you interested in quitting smoking/vaping? If the patient is ready to quit, the five successful interventions are the “5 A’s”: Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange. Ask – Identify and document smoking status for every patient at every visit. Advise – In a clear, strong, and personalized manner, urge every user to quit. Assess – Is the user willing to make a quitting attempt at this time? Assist – For the patient willing to make a quitting attempt, use counseling and pharmacotherapy to help them quit. Arrange – Schedule follow-up contact, in person or by telephone, preferably within the first week after the quit date.[2] |

Life Span Considerations

Depending on the age and capability of the child, subjective data may also need to be retrieved from a parent and/or legal guardian.

Pediatric

- Is your child up-to-date with recommended immunizations?

- Is your child experiencing any cold symptoms (such as runny nose, cough, or nasal congestion)?

- How is your child’s appetite? Is there any decrease or change recently in appetite or wet diapers?

- Does your child have any hospitalization history related to respiratory illness?

- Did your child have any history of frequent ear infections as an infant?

Older Adult

- Have you noticed a change in your breathing?

- Do you get short of breath with activities that you did not before?

- Can you describe your energy level? Is there any change from previous?

Objective Assessment

A focused respiratory objective assessment includes interpretation of vital signs; inspection of the patient’s breathing pattern, skin color, and respiratory status; palpation to identify abnormalities; and auscultation of lung sounds using a stethoscope. For more information regarding interpreting vital signs, see the “General Survey” chapter. The nurse must have an understanding of what is expected for the patient’s age, gender, development, race, culture, environmental factors, and current health condition to determine the meaning of the data that is being collected.

Evaluate Vital Signs

The vital signs may be taken by the nurse or delegated to unlicensed assistive personnel such as a nursing assistant or medical assistant. Evaluate the respiratory rate and pulse oximetry readings to verify the patient is stable before proceeding with the physical exam. The normal range of a respiratory rate for an adult is 12-20 breaths per minute at rest, and the normal range for oxygen saturation of the blood is 94–98% (SpO₂)[3] Bradypnea is less than 12 breaths per minute, and tachypnea is greater than 20 breaths per minute.

Inspection

Inspection during a focused respiratory assessment includes observation of level of consciousness, breathing rate, pattern and effort, skin color, chest configuration, and symmetry of expansion.

- Assess the level of consciousness. The patient should be alert and cooperative. Hypoxemia (low blood levels of oxygen) or hypercapnia (high blood levels of carbon dioxide) can cause a decreased level of consciousness, irritability, anxiousness, restlessness, or confusion.

- Obtain the respiratory rate over a full minute. The normal range for the respiratory rate of an adult is 12-20 breaths per minute.

- Observe the breathing pattern, including the rhythm, effort, and use of accessory muscles. Breathing effort should be nonlabored and in a regular rhythm. Observe the depth of respiration and note if the respiration is shallow or deep. Pursed-lip breathing, nasal flaring, audible breathing, intercostal retractions, anxiety, and use of accessory muscles are signs of respiratory difficulty. Inspiration should last half as long as expiration unless the patient is active, in which case the inspiration-expiration ratio increases to 1:1.

- Observe pattern of expiration and patient position. Patients who experience difficulty expelling air, such as those with emphysema, may have prolonged expiration cycles. Some patients may experience difficulty with breathing specifically when lying down. This symptom is known as orthopnea. Additionally, patients who are experiencing significant breathing difficulty may experience most relief while in a “tripod” position. This can be achieved by having the patient sit at the side of the bed with legs dangling toward the floor. The patient can then rest their arms on an overbed table to allow for maximum lung expansion. This position mimics the same position you might take at the end of running a race when you lean over and place your hands on your knees to “catch your breath.”

- Observe the patient’s color in their lips, face, hands, and feet. Patients with light skin tones should be pink in color. For those with darker skin tones, assess for pallor on the palms, conjunctivae, or inner aspect of the lower lip. Cyanosis is a bluish discoloration of the skin, lips, and nail beds, which may indicate decreased perfusion and oxygenation. Pallor is the loss of color, or paleness of the skin or mucous membranes and usually the result of reduced blood flow, oxygenation, or decreased number of red blood cells.

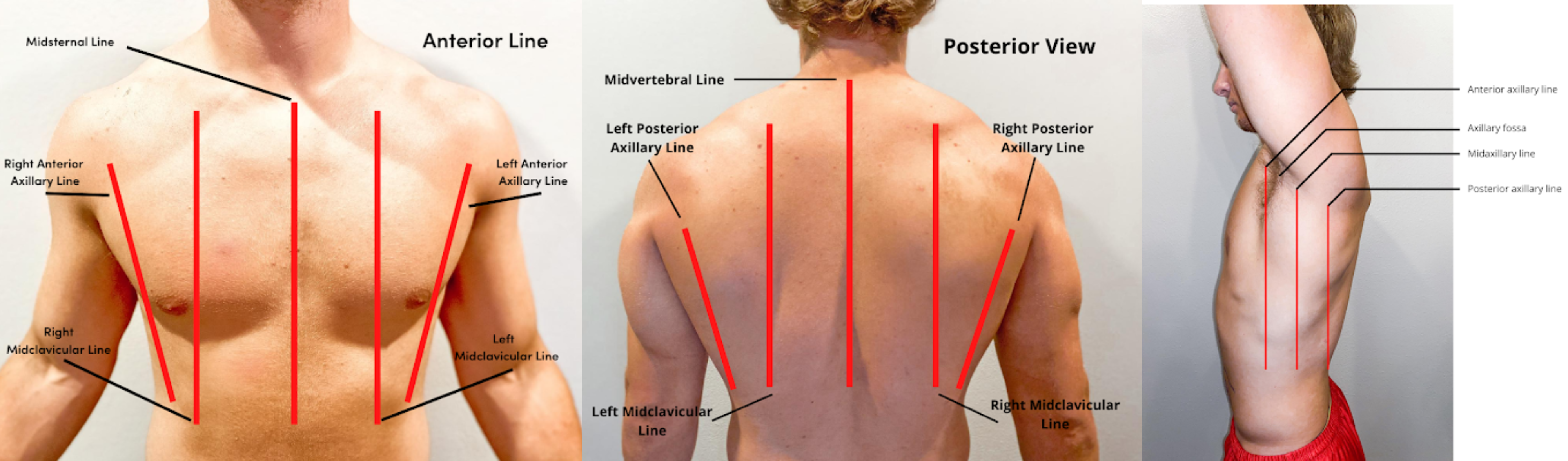

- Inspect the chest for symmetry and configuration. The trachea should be midline, and the clavicles should be symmetrical. See Figure 10.2[4] for visual landmarks when inspecting the thorax anteriorly, posteriorly, and laterally. Note the location of the ribs, sternum, clavicle, and scapula, as well as the underlying lobes of the lungs.

- Chest movement should be symmetrical on inspiration and expiration.

- Observe the anterior-posterior diameter of the patient’s chest and compare to the transverse diameter. The expected anteroposterior-transverse ratio should be 1:2. A patient with a 1:1 ratio is described as barrel-chested. This ratio is often seen in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease due to hyperinflation of the lungs. See Figure 10.3[5] for an image of a patient with a barrel chest.

- Older patients may have changes in their anatomy, such as kyphosis, an outward curvature of the spine.

- Inspect the fingers for clubbing if the patient has a history of chronic respiratory disease. Clubbing is a bulbous enlargement of the tips of the fingers due to chronic hypoxia. See Figure 10.4[6] for an image of clubbing.

Palpation

- Palpation of the chest may be performed to investigate for areas of abnormality related to injury or procedural complications. For example, if a patient has a chest tube or has recently had one removed, the nurse may palpate near the tube insertion site to assess for areas of air leak or crepitus. Crepitus feels like a popping or crackling sensation when the skin is palpated and is a sign of air trapped under the subcutaneous tissues. If palpating the chest, use light pressure with the fingertips to examine the anterior and posterior chest wall. Chest palpation may be performed to assess specifically for growths, masses, crepitus, pain, or tenderness.

- Confirm symmetric chest expansion by placing your hands on the anterior or posterior chest at the same level, with thumbs over the sternum anteriorly or the spine posteriorly. As the patient inhales, your thumbs should move apart symmetrically. Unequal expansion can occur with pneumonia, thoracic trauma, such as fractured ribs, or pneumothorax.

Auscultation

Using the diaphragm of the stethoscope, listen to the movement of air through the airways during inspiration and expiration. Instruct the patient to take deep breaths through their mouth. Listen through the entire respiratory cycle because different sounds may be heard on inspiration and expiration. As you move across the different lung fields, the sounds produced by airflow vary depending on the area you are auscultating because the size of the airways change.

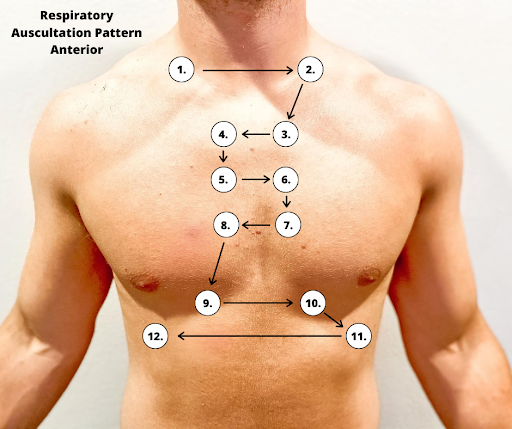

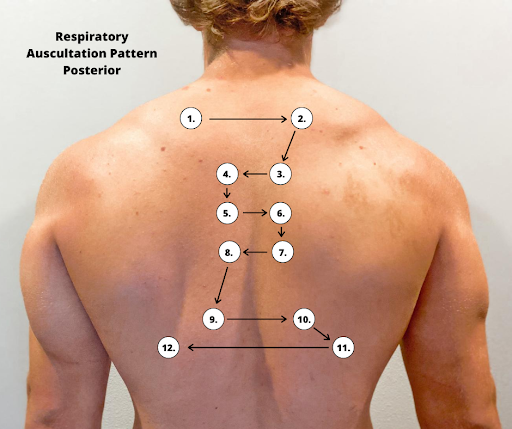

Correct placement of the stethoscope during auscultation of lung sounds is important to obtain a quality assessment. The stethoscope should not be performed over clothes or hair because these may create inaccurate sounds from friction. The best position to listen to lung sounds is with the patient sitting upright; however, if the patient is acutely ill or unable to sit upright, turn them side to side in a lying position. Avoid listening over bones, such as the scapulae or clavicles or over the female breasts to ensure you are hearing adequate sound transmission. Listen to sounds from side to side rather than down one side and then down the other side. This side-to-side pattern allows you to compare sounds in symmetrical lung fields. See Figures 10.5[7] and 10.6[8] for landmarks of stethoscope placement over the anterior and posterior chest wall.

Expected Breath Sounds

It is important upon auscultation to have awareness of expected breath sounds in various anatomical locations.

- Bronchial breath sounds are heard over the trachea and larynx and are high-pitched and loud.

- Bronchovesicular sounds are medium-pitched and heard over the major bronchi.

- Vesicular breath sounds are heard over the lung surfaces, are lower-pitched, and often described as soft, rustling sounds.

Adventitious Lung Sounds

Adventitious lung sounds are sounds heard in addition to normal breath sounds. They most often indicate an airway problem or disease, such as accumulation of mucus or fluids in the airways, obstruction, inflammation, or infection. These sounds include rales/crackles, rhonchi/wheezes, stridor, and pleural rub:

- Fine crackles, also called rales, are popping or crackling sounds heard on inspiration that occur in association with conditions that cause fluid to accumulate within the alveolar and interstitial spaces, such as heart failure or pneumonia. The sound is similar to that produced by rubbing strands of hair together close to your ear.

- Wheezes are whistling-type noises produced during expiration (and sometimes inspiration) when air is forced through airways narrowed by bronchoconstriction or associated mucosal edema. For example, patients with asthma commonly have wheezing.

- Stridor is heard only on inspiration. It is associated with mechanical obstruction at the level of the trachea/upper airway.

- Pleural rub may be heard on either inspiration or expiration and sounds like the rubbing together of leather. A pleural rub is heard when there is inflammation of the lung pleura, resulting in friction as the surfaces rub against each other.[9]

Life Span Considerations

Children

There are various respiratory assessment considerations that should be noted with assessment of children.

- The respiratory rate in children less than 12 months of age can range from 30-60 breaths per minute, depending on whether the infant is asleep or active.

- Infants have irregular or periodic newborn breathing in the first few weeks of life; therefore, it is important to count the respirations for a full minute. During this time, you may notice periods of apnea lasting up to 10 seconds. This is not abnormal unless the infant is showing other signs of distress. Signs of respiratory distress in infants and children include nasal flaring and sternal or intercostal retractions.

- Up to three months of age, infants are considered “obligate” nose-breathers, meaning their breathing is primarily through the nose.

- The anteroposterior-transverse ratio is typically 1:1 until the thoracic muscles are fully developed around six years of age.

Older Adults

As the adult person ages, the cartilage and muscle support of the thorax becomes weakened and less flexible, resulting in a decrease in chest expansion. Older adults may also have weakened respiratory muscles, and breathing may become more shallow. The anteroposterior-transverse ratio may be 1:1 if there is significant curvature of the spine (kyphosis).

Percussion

Percussion is an advanced respiratory assessment technique that is used by advanced practice nurses and other health care providers to gather additional data in the underlying lung tissue. By striking the fingers of one hand over the fingers of the other hand, a sound is produced over the lung fields that helps determine if fluid is present. Dull sounds are heard with high-density areas, such as pneumonia or atelectasis, whereas clear, low-pitched, hollow sounds are heard in normal lung tissue.

![]()

- Because infants breathe primarily through the nose, nasal congestion can limit the amount of air getting into the lungs.

- Attempt to assess an infant’s respiratory rate while the infant is at rest and content rather than when the infant is crying. Counting respirations by observing abdominal breathing movements may be easier for the novice nurse than counting breath sounds, as it can be difficult to differentiate lung and heart sounds when auscultating newborns.

- Auscultation of lungs during crying is not a problem. It will enhance breath sounds.

- The older patient may have a weakening of muscles that support respiration and breathing. Therefore, the patient may report tiring easily during the assessment when taking deep breaths. Break up the assessment by listening to the anterior lung sounds and then the heart sounds and allowing the patient to rest before listening to the posterior lung sounds.

- Patients with end-stage COPD may have diminished lung sounds due to decreased air movement. This abnormal assessment finding may be the patient’s baseline or normal and might also include wheezes and fine crackles as a result of chronic excess secretions and/or bronchoconstriction.[10],[11]

Expected Versus Unexpected Findings

See Table 10.3b for a comparison of expected versus unexpected findings when assessing the respiratory system.[12]

Table 10.3b Expected Versus Unexpected Respiratory Assessment Findings

| Assessment | Expected Findings | Unexpected Findings (Document and notify provider if a new finding*) |

|---|---|---|

| Inspection | Work of breathing effortless

Regular breathing pattern Respiratory rate within normal range for age Chest expansion symmetrical Absence of cyanosis or pallor Absence of accessory muscle use, retractions, and/or nasal flaring Anteroposterior: transverse diameter ratio 1:2 |

Labored breathing

Irregular rhythm Increased or decreased respiratory rate Accessory muscle use, pursed-lip breathing, nasal flaring (infants), and/or retractions Presence of cyanosis or pallor Asymmetrical chest expansion Clubbing of fingernails |

| Palpation | No pain or tenderness with palpation. Skin warm and dry; no crepitus or masses | Pain or tenderness with palpation, crepitus, palpable masses, or lumps |

| Percussion | Clear, low-pitched, hollow sound in normal lung tissue | Dull sounds heard with high-density areas, such as pneumonia or atelectasis |

| Auscultation | Bronchovesicular and vesicular sounds heard over appropriate areas

Absence of adventitious lung sounds |

Diminished lung sounds

Adventitious lung sounds, such as fine crackles/rales, wheezing, stridor, or pleural rub |

| *CRITICAL CONDITIONS to report immediately | Decreased oxygen saturation <92%[13]

Pain Worsening dyspnea Decreased level of consciousness, restlessness, anxiousness, and/or irritability |

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Massey, D., & Meredith, T. (2011). Respiratory assessment 1: Why do it and how to do it? British Journal of Cardiac Nursing, 5(11), 537–541. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjca.2010.5.11.79634 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Nursing Pharmacology by Open RN licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- "Anterior_Chest_Lines.png," "Posterior_Chest_Lines.png," and "Lateral_Chest_Lines.png" by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College are licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Normal A-P Chest Image.jpg" and "Barrel Chest.jpg" by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College are licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Clubbing of fingers in IPF.jpg” by IPFeditor is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- "Anterior Respiratory Auscultation Pattern.png" by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- "Posterior Respiratory Auscultation Pattern.png" by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Honig, E. (1990). An overview of the pulmonary system. In Walker, H. K., Hall, W. D., Hurst, J. W. (Eds.), Clinical methods: The history, physical, and laboratory examinations (3rd ed.). Butterworths. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK356/ ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Hill, B., & Annesley, S. H. (2020). Monitoring respiratory rate in adults. British Journal of Nursing, 29(1), 12–16. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2020.29.1.12 ↵

To perform and document an accurate assessment of the head and neck, it is important to understand their basic anatomy and physiology.

Anatomy

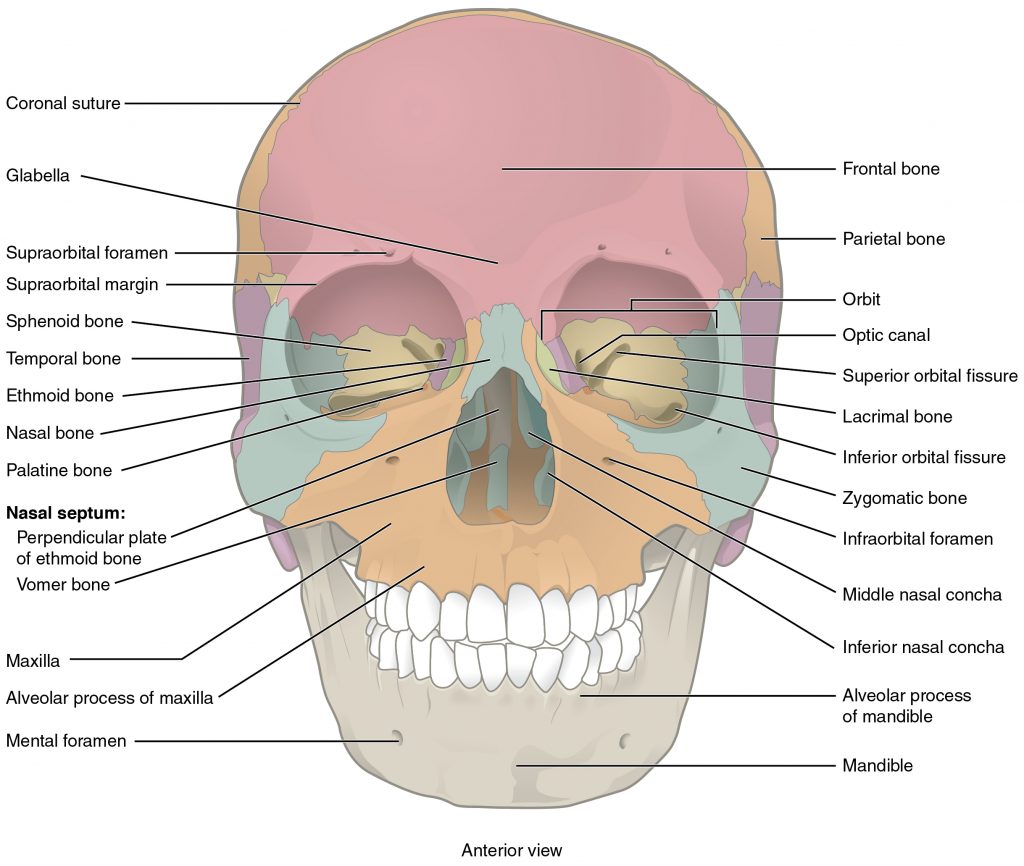

Skull

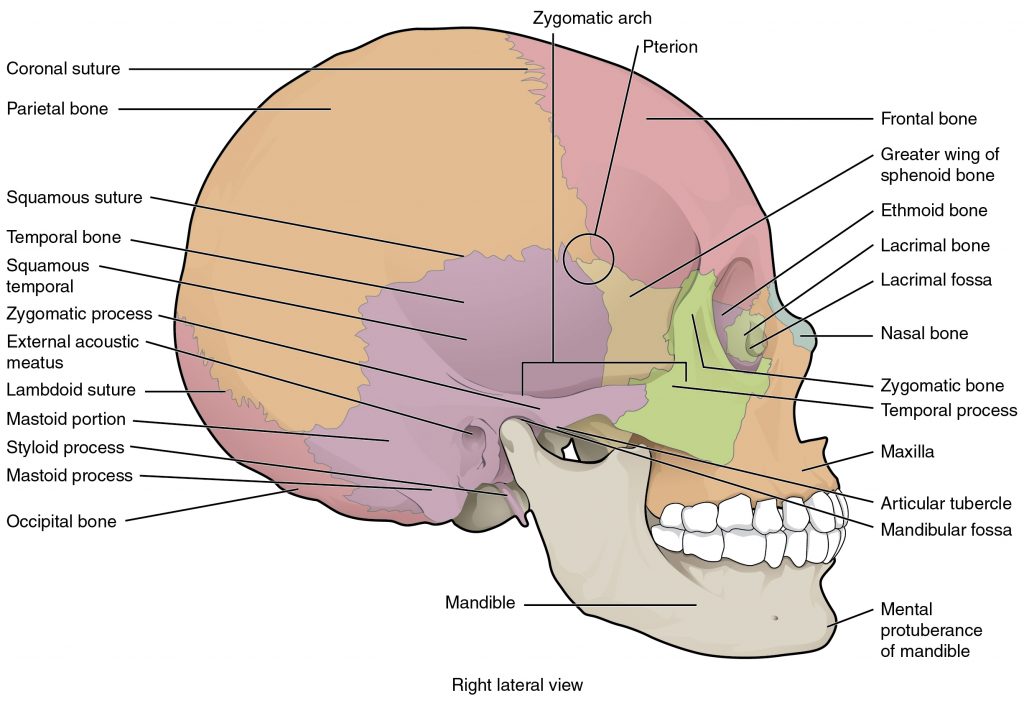

The anterior skull consists of facial bones that provide the bony support for the eyes and structures of the face. This anterior view of the skull is dominated by the openings of the orbits, the nasal cavity, and the upper and lower jaws. See Figure 7.1[1] for an illustration of the skull. The orbit is the bony socket that houses the eyeball and the muscles that move the eyeball. Inside the nasal area of the skull, the nasal cavity is divided into halves by the nasal septum that consists of both bone and cartilage components. The mandible forms the lower jaw and is the only movable bone in the skull. The maxilla forms the upper jaw and supports the upper teeth.[2]

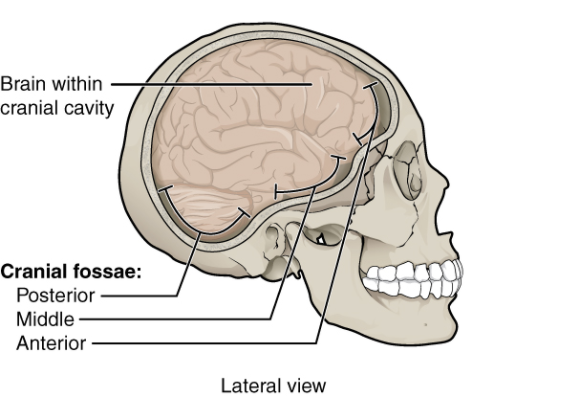

The brain case surrounds and protects the brain that occupies the cranial cavity. See Figure 7.2[3] for an image of the brain within the cranial cavity. The brain case consists of eight bones, including the paired parietal and temporal bones plus the unpaired frontal, occipital, sphenoid, and ethmoid bones.[4]

A suture is an interlocking joint between adjacent bones of the skull and is filled with dense, fibrous connective tissue that unites the bones. In a newborn infant, the pressure from vaginal delivery compresses the head and causes the bony plates to overlap at the sutures, creating a small ridge. Over the next few days, the head expands, the overlapping disappears, and the edges of the bony plates meet edge to edge. This is the normal position for the remainder of the life span and the sutures become immobile.

See Figure 7.3[5] for an illustration of two of the sutures, the coronal and squamous sutures, on the lateral view of the head. The coronal suture is seen on the top of the skull. It runs from side to side across the skull and joins the frontal bone to the right and left parietal bones. The squamous suture is located on the lateral side of the skull. It unites the squamous portion of the temporal bone with the parietal bone. At the intersection of the coronal and squamous sutures is the pterion, a small, capital H-shaped suture line region that unites the frontal bone, parietal bone, temporal bone, and greater wing of the sphenoid bone. The pterion is an important clinical landmark because located immediately under it, inside the skull, is a major branch of an artery that supplies the brain. A strong blow to this region can fracture the bones around the pterion. If the underlying artery is damaged, bleeding can cause the formation of a collection of blood, called a hematoma, between the brain and interior of the skull, which can be life-threatening.[6]

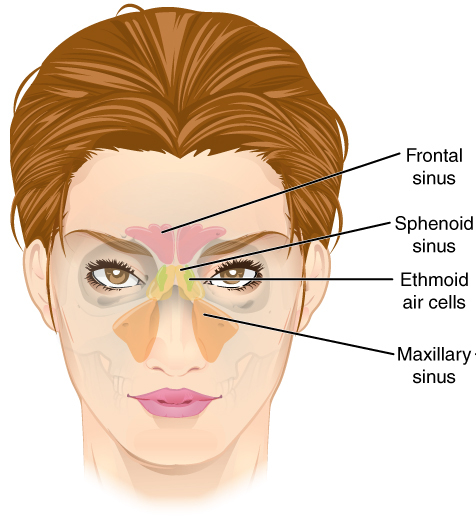

Paranasal Sinuses

The paranasal sinuses are hollow, air-filled spaces located within the skull. See Figure 7.4[7] for an illustration of the sinuses. The sinuses connect with the nasal cavity and are lined with nasal mucosa. They reduce bone mass, lightening the skull, and also add resonance to the voice. When a person has a cold or sinus congestion, the mucosa swells and produces excess mucus that often obstructs the narrow passageways between the sinuses and the nasal cavity. The resulting pressure produces pain and discomfort.[8]

Each of the paranasal sinuses is named for the skull bone that it occupies. The frontal sinus is located just above the eyebrows within the frontal bone. The largest sinus, the maxillary sinus, is paired and located within the right and left maxillary bones just below the orbits. The maxillary sinuses are most commonly involved during sinus infections. The sphenoid sinus is a single, midline sinus located within the body of the sphenoid bone. The lateral aspects of the ethmoid bone contain multiple small spaces separated by very thin, bony walls. Each of these spaces is called an ethmoid air cell.

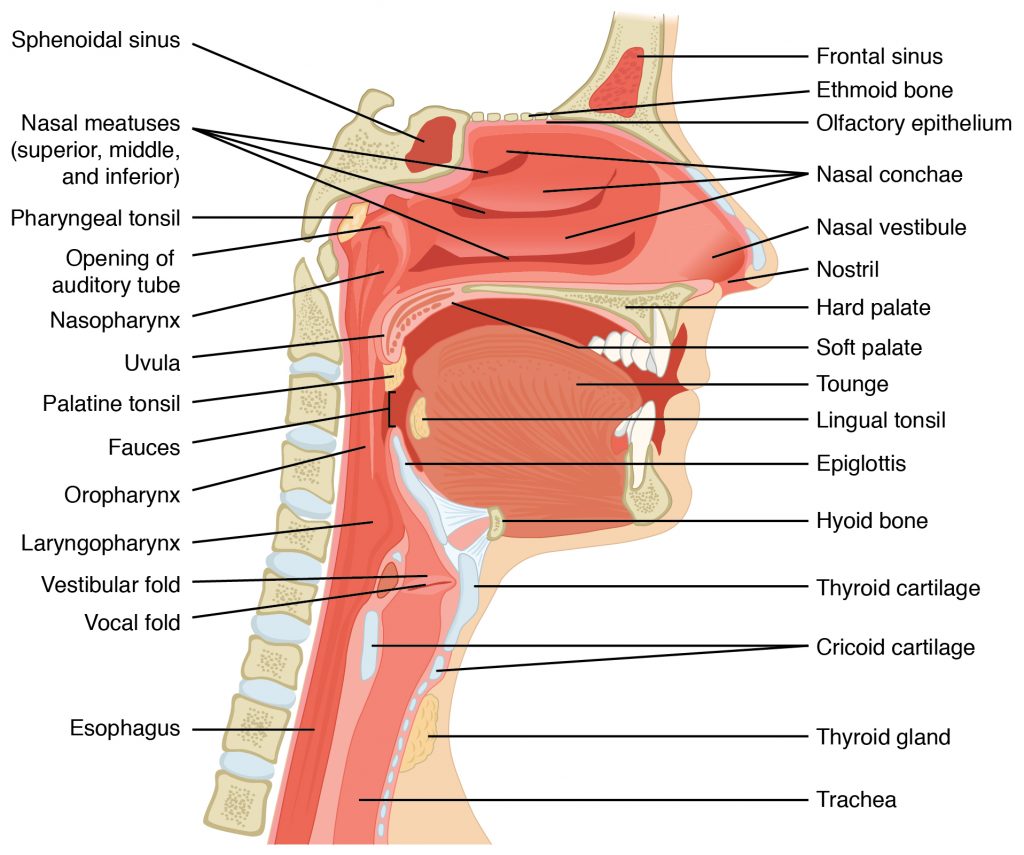

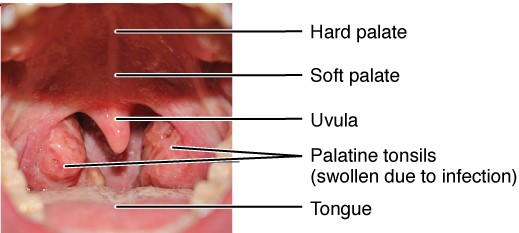

Anatomy of Nose, Pharynx, and Mouth

See Figure 7.5[9] to review the anatomy of the head and neck. The major entrance and exit for the respiratory system is through the nose. The bridge of the nose consists of bone, but the protruding portion of the nose is composed of cartilage. The nares are the nostril openings that open into the nasal cavity and are separated into left and right sections by the nasal septum. The floor of the nasal cavity is composed of the palate. The hard palate is located at the anterior region of the nasal cavity and is composed of bone. The soft palate is located at the posterior portion of the nasal cavity and consists of muscle tissue. The uvula is a small, teardrop-shaped structure located at the apex of the soft palate. Both the uvula and soft palate move like a pendulum during swallowing, swinging upward to close off the nasopharynx and prevent ingested materials from entering the nasal cavity.[10]

As air is inhaled through the nose, the paranasal sinuses warm and humidify the incoming air as it moves into the pharynx. The pharynx is a tube-lined mucous membrane that begins at the nasal cavity and is divided into three major regions: the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, and the laryngopharynx.[11]

The nasopharynx serves only as an airway. At the top of the nasopharynx is the pharyngeal tonsil, commonly referred to as the adenoids. Adenoids are lymphoid tissue that trap and destroy invading pathogens that enter during inhalation. They are large in children but tend to regress with age and may even disappear.[12]

The oropharynx is a passageway for both air and food. The oropharynx is bordered superiorly by the nasopharynx and anteriorly by the oral cavity. The oropharynx contains two sets of tonsils, the palatine and lingual tonsils. The palatine tonsil is located laterally in the oropharynx, and the lingual tonsil is located at the base of the tongue. Similar to the pharyngeal tonsil, the palatine and lingual tonsils are composed of lymphoid tissue and trap and destroy pathogens entering the body through the oral or nasal cavities. See Figure 7.6[13] for an image of the oral cavity and oropharynx with enlarged palatine tonsils.

The laryngopharynx is inferior to the oropharynx and posterior to the larynx. It continues the route for ingested material and air until its inferior end where the digestive and respiratory systems diverge. Anteriorly, the laryngopharynx opens into the larynx and posteriorly, it enters the esophagus that leads to the stomach. The larynx connects the pharynx to the trachea and helps regulate the volume of air that enters and leaves the lungs. It also contains the vocal cords that vibrate as air passes over them to produce the sound of a person’s voice. The trachea extends from the larynx to the lungs. The epiglottis is a flexible piece of cartilage that covers the opening of the trachea during swallowing to prevent ingested material from entering the trachea.[14]

Muscles and Nerves of the Head and Neck

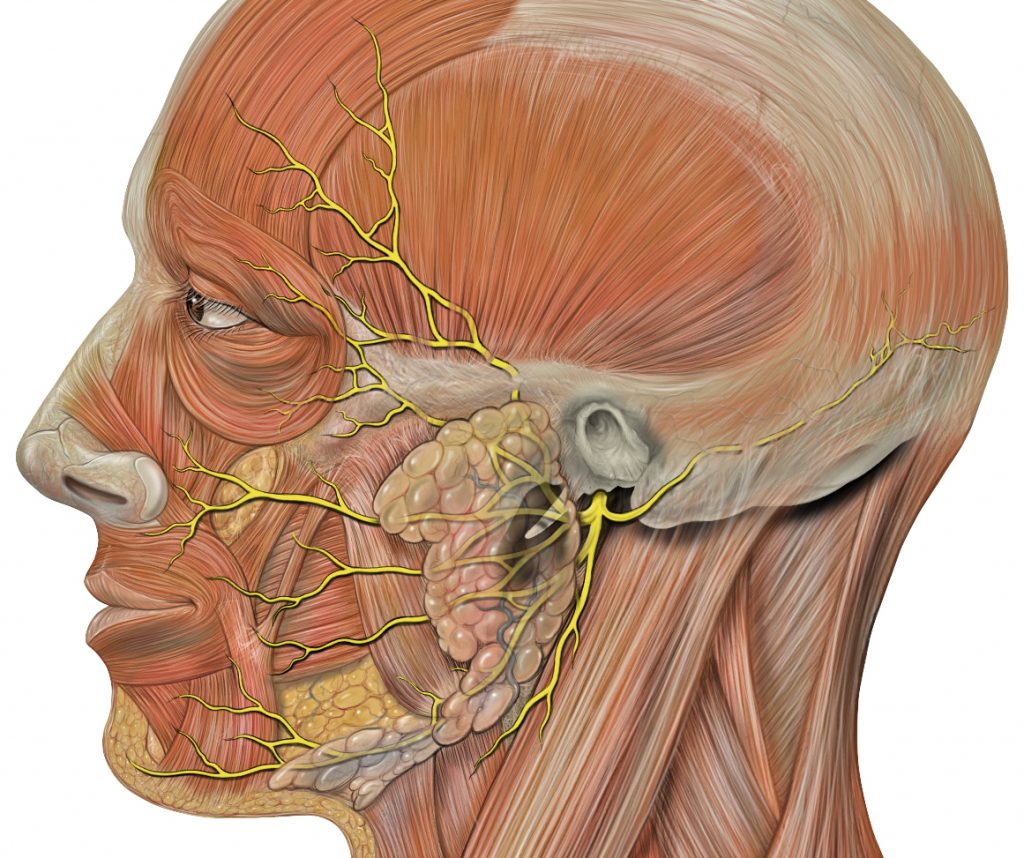

Facial Muscles

Several nerves innervate the facial muscles to create facial expressions. See Figure 7.7[15] for an illustration of nerves innervating facial muscles. These nerves and muscles are tested during a cranial nerve exam. See more information about performing a cranial nerve exam in the “Neurological Assessment” chapter.

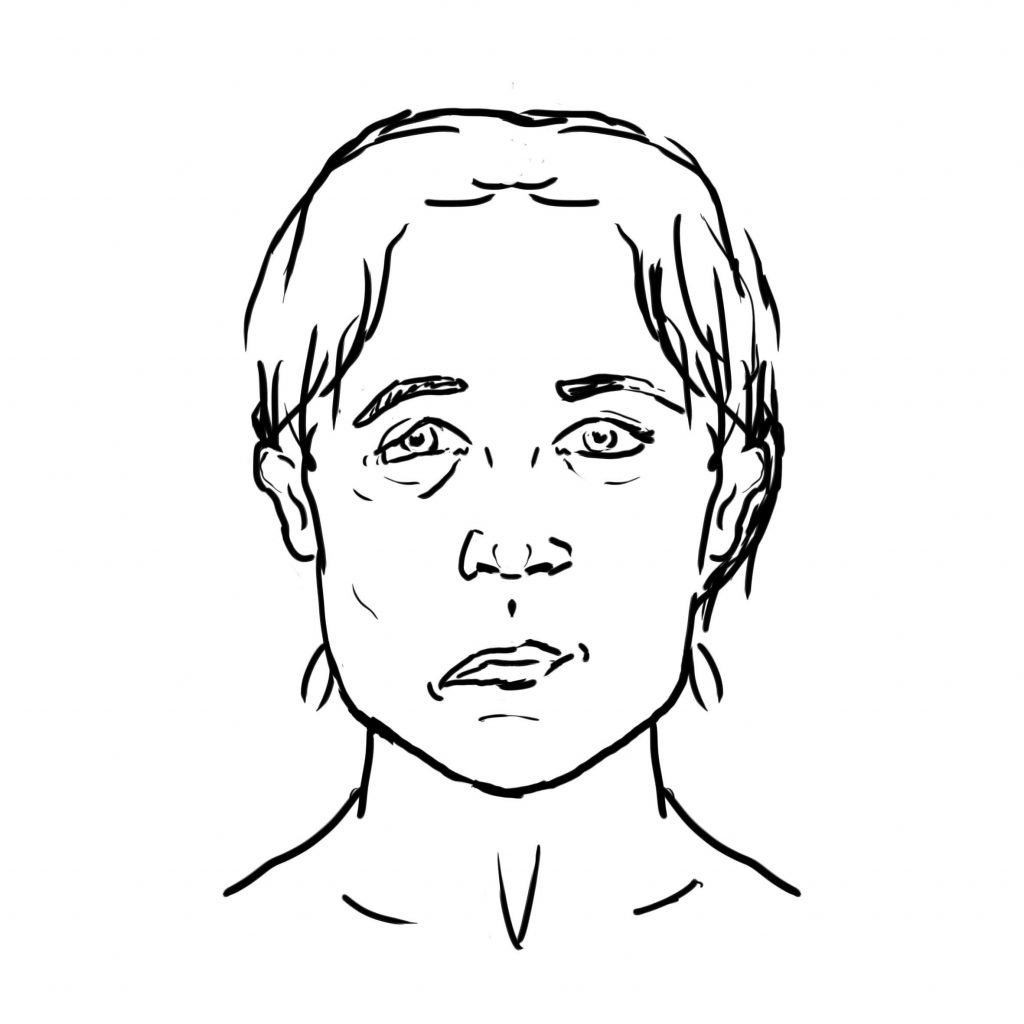

When a patient is experiencing a cerebrovascular accident (i.e., stroke), it is common for facial drooping to occur. Facial drooping is an asymmetrical facial expression that occurs due to damage of the nerve innervating a specific part of the face. See Figure 7.8[16] for an image of facial drooping occurring on the patient’s right side of their face.

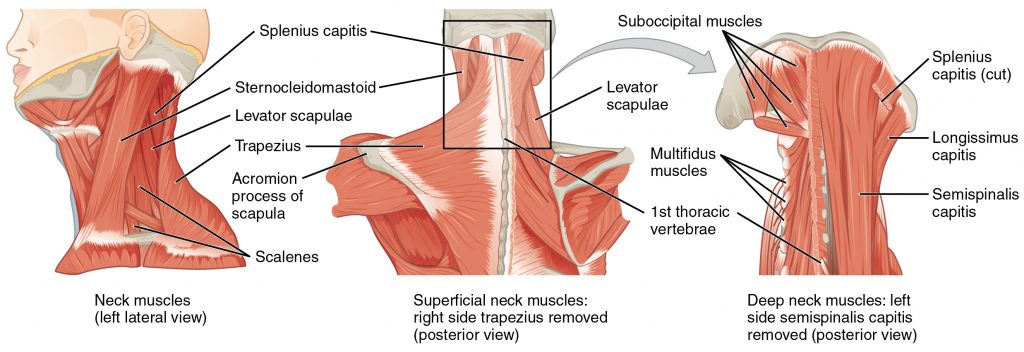

Neck Muscles

The muscles of the anterior neck assist in swallowing and speech by controlling the positions of the larynx and the hyoid bone, a horseshoe-shaped bone that functions as a solid foundation on which the tongue can move. The head, attached to the top of the vertebral column, is balanced, moved, and rotated by the neck muscles. When these muscles act unilaterally, the head rotates. When they contract bilaterally, the head flexes or extends. The major muscle that laterally flexes and rotates the head is the sternocleidomastoid. The trapezius muscle elevates the shoulders (shrugging), pulls the shoulder blades together, and tilts the head backwards. See Figure 7.9[17] for an illustration of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles.[18]Both of these muscles are tested during a cranial nerve assessment. See more information about cranial nerve assessment in the “Neurological Assessment” chapter.

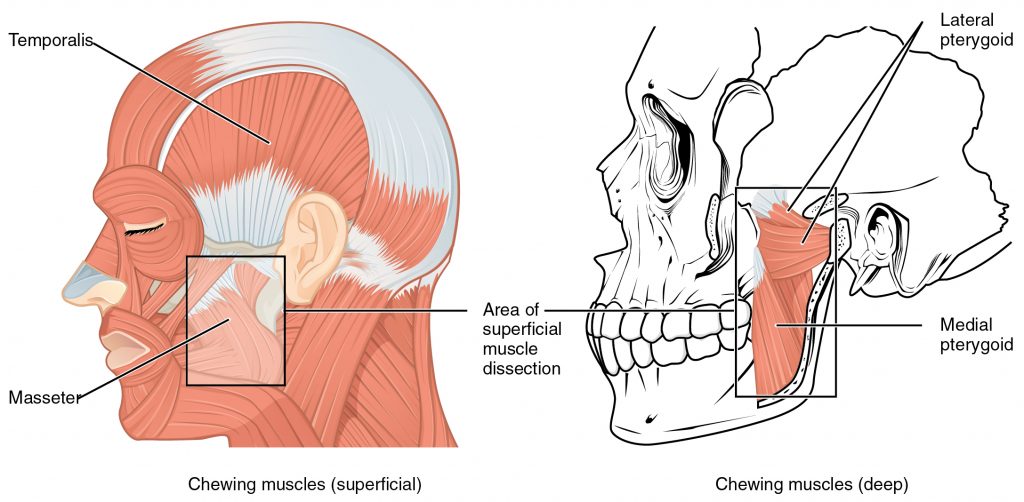

Jaw Muscles

The masseter muscle is the main muscle used for chewing because it elevates the mandible (lower jaw) to close the mouth. It is assisted by the temporalis muscle that retracts the mandible. The temporalis muscle can be felt moving by placing fingers on the patient’s temple as they chew. See Figure 7.10[19] for an illustration of the masseter and temporalis muscles.[20]

Tongue Muscles

Muscles of the tongue are necessary for chewing, swallowing, and speech. Because it is so moveable, the tongue facilitates complex speech patterns and sounds.[21]

Airway and Unconsciousness

When a patient becomes unconscious and is lying supine, the tongue often moves backwards and blocks the airway. This is why it is important to open the airway when performing CPR by using a chin-thrust maneuver. See Figure 7.11[22] for an image of the tongue blocking the airway. In a similar manner, when a patient is administered general anesthesia during surgery, the tongue relaxes and can block the airway. For this reason, endotracheal intubation is performed during surgery with general anesthesia by placing a tube into the trachea to maintain an open airway to the lungs. After surgery, patients often report a sore or scratchy throat for a few days due to the endotracheal intubation.[23]

Swallowing

Swallowing is a complex process that uses 50 pairs of muscles and many nerves to receive food in the mouth, prepare it, and move it from the mouth to the stomach. Swallowing occurs in three stages. During the first stage, called the oral phase, the tongue collects the food or liquid and makes it ready for swallowing. The tongue and jaw move solid food around in the mouth so it can be chewed and made the right size and texture to swallow by mixing food with saliva. The second stage begins when the tongue pushes the food or liquid to the back of the mouth. This triggers a swallowing response that passes the food through the pharynx. During this phase, called the pharyngeal phase, the epiglottis closes off the larynx and breathing stops to prevent food or liquid from entering the airway and lungs. The third stage begins when food or liquid enters the esophagus and it is carried to the stomach. The passage through the esophagus, called the esophageal phase, usually occurs in about three seconds.[24]

View the following video from Medline Plus on the Swallowing Process:

Dysphagia is the medical term for swallowing difficulties that occur when there is a problem with the nerves or structures involved in the swallowing process.[26] Nurses are often the first to notice signs of dysphagia in their patients that can occur due to a multitude of medical conditions such as a stroke, head injury, or dementia. For more information about the symptoms, screening, and treatment for dysphagia, go to the "Common Conditions of the Head and Neck" section.

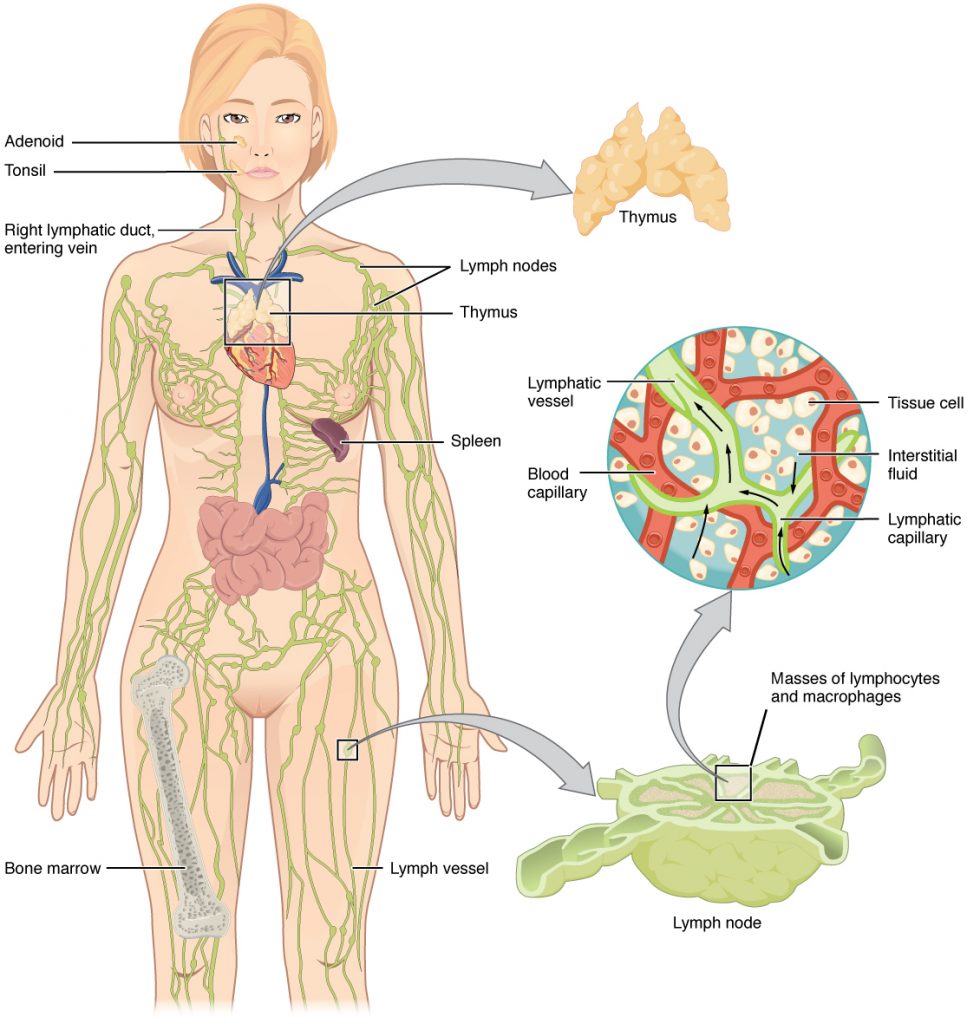

Lymphatic System

The lymphatic system is the system of vessels, cells, and organs that carries excess interstitial fluid to the bloodstream and filters pathogens from the blood through lymph nodes found near the neck, armpits, chest, abdomen, and groin. See Figure 7.12[27] and Figure 7.13[28] for an illustration of the lymph nodes found in the head and neck regions. When a person is fighting off an infection, the lymph nodes in that region become enlarged, indicating an active immune response to infection.[29]

![]“Cervical lymph nodes and level.png” by Mikael Häggström, M.D. is licensed under CC0 1.0 Illustration of lymph nodes in head and neck, with labels](https://nicoletcollege.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/54/2022/04/Cervical_lymph_nodes_and_levels-1024x551.png)

Use the checklist below to review the steps for completion of "Applying and Removing Personal Protective Equipment."[30]

Steps

Disclaimer: Always review and follow agency policy regarding this specific skill.

- Check the provider's order for the type of precautions.

- Ensure that all supplies are available before check-off begins: isolation cart, gowns, gloves, mask, eye/face shields, shoes, and head cover.

- Perform hand hygiene.

- Apply PPE in the correct order:

- 1st (GOWN): Gown should cover all outer garments. Pull the sleeves down to the wrists, and tie at neck & waist.

- 2nd (MASK/RESPIRATOR): Apply surgical mask or N95 respirator if indicated by transmission-based precaution. Fit the mask around the nose and chin, securing bands around ears or tie straps at top of head and base of neck.

- 3rd (EYE PROTECTION): Apply goggles/face shield if indicated for patient condition or transmission-based precautions.

- 4th (CLEAN GLOVES): Pull on gloves to cover the wrist of the gown.

- Remove PPE in the correct order:

- 1st REMOVE GLOVES: REMEMBER: GLOVE TO GLOVE; SKIN TO SKIN. Do not touch contaminated gloves to your skin. Take off the contaminated glove with your gloved hand, wrapping the contaminated glove in the palm of your gloved hand. Take off the glove with your bare hand to the skin of your wrist, moving inside of the glove to remove the contaminated glove inside out over the other glove. Note: If the gown is tied in front, untie it prior to removing your glove.

- 2nd REMOVE GOWN: Untie all ties (or unsnap all buttons). Some gown ties can be broken rather than untied. Do so in a gentle manner, avoiding a forceful movement. Reach up to the shoulders and carefully pull the gown down and away from the body. Rolling the gown down is an acceptable approach. Dispose in trash receptacle.

- 3rd PERFORM HAND HYGIENE.

- 4th REMOVE FACE SHIELD or GOGGLES: Carefully remove face shield or goggles by grabbing the strap and pulling upwards and away from head. Do not touch the front of face shield or goggles.

- 5th REMOVE MASK or RESPIRATOR: Do not touch the front of the face shield or goggles.

- Respirator: Remove the bottom strap by touching only the strap and bringing it carefully over the head. Grasp the top strap and bring it carefully over the head, and then pull the respirator away from the face without touching the front of the respirator.

- Face mask: Carefully untie (or unhook from the ears) and pull it away from the face without touching the front.

- 6th PERFORM HAND HYGIENE after removing the mask.

Airborne precautions: Infection prevention and control interventions to be used in addition to standard precautions for diseases spread by airborne transmission, such as measles and tuberculosis.

Asepsis: A state of being free of disease-causing microorganisms.

Aseptic non-touch technique: A standardized technique, supported by evidence, to maintain asepsis and standardize practice.

Aseptic technique (medical asepsis): The purposeful reduction of pathogen numbers while preventing microorganism transfer from one person or object to another. This technique is commonly used to perform invasive procedures, such as IV starts or urinary catheterization.

Contact precautions: Infection prevention and control interventions to be used in addition to standard precautions for diseases spread by contact with the patient, their body fluids, or their surroundings, such as C-diff, MRSA, VRE, and RSV.

Doff: To take off or remove personal protective equipment, such as gloves or a gown.

Don: To put on equipment for personal protection, such as gloves or a gown.

Droplet precautions: Infection prevention and control interventions to be used in addition to standard precautions; used for diseases spread by large respiratory droplets such as influenza, COVID-19, or pertussis.

Five moments of hand hygiene: Hand hygiene should be performed during the five moments of patient care: immediately before touching a patient; before performing an aseptic task or handling invasive devices; before moving from a soiled body site to a clean body site on a patient; after touching a patient or their immediate environment; after contact with blood, body fluids, or contaminated surfaces (with or without glove use); and immediately after glove removal.

Hand hygiene: A way of cleaning one’s hands to substantially reduce the number of pathogens and other contaminants (e.g., dirt, body fluids, chemicals, or other unwanted substances) to prevent disease transmission or integumentary harm, typically using soap, water, and friction. An alcohol-based hand rub solution may be appropriate hand hygiene for hands not visibly soiled.

Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs): Unintended infections caused by care received in a health care setting.

Key part: Any sterile part of equipment used during an aseptic procedure, such as needle hubs, syringe tips, dressings, etc.

Key site: The site contacted during an aseptic procedure, such as nonintact skin, a potential insertion site, or an access site used for medical devices connected to the patients. Examples of key sites include the insertion or access site for intravenous (IV) devices, urinary catheters, and open wounds.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Personal protective equipment, such as gloves, gowns, face shields, goggles, and masks, used to prevent transmission of disease from patient to patient, patient to health care provider, and health care provider to patient.

Standard precautions: The minimum infection prevention practices that apply to all patient care, regardless of suspected or confirmed infection status of the patient, in any setting where health care is delivered.

Sterile technique (surgical asepsis): Techniques used to eliminate every potential microorganism in and around a sterile field while maintaining objects and areas as free from microorganisms as possible. This technique is the standard of care for surgical procedures, invasive wound management, and central line care.

Headache

A headache is a common type of pain that patients experience in everyday life and a major reason for missed time at work or school. Headaches range greatly in severity of pain and frequency of occurrence. For example, some patients experience mild headaches once or twice a year, whereas others experience disabling migraine headaches more than 15 days a month. Severe headaches such as migraines may be accompanied by symptoms of nausea or increased sensitivity to noise or light. Primary headaches occur independently and are not caused by another medical condition. Migraine, cluster, and tension-type headaches are types of primary headaches. Secondary headaches are symptoms of another health disorder that causes pain-sensitive nerve endings to be pressed on or pulled out of place. They may result from underlying conditions including fever, infection, medication overuse, stress or emotional conflict, high blood pressure, psychiatric disorders, head injury or trauma, stroke, tumors, and nerve disorders such as trigeminal neuralgia, a chronic pain condition that typically affects the trigeminal nerve on one side of the cheek.[31]

Not all headaches require medical attention, but some types of headaches can signify a serious disorder and require prompt medical care. Symptoms of headaches that require immediate medical attention include a sudden, severe headache unlike any the patient has ever had; a sudden headache associated with a stiff neck; a headache associated with convulsions, confusion, or loss of consciousness; a headache following a blow to the head; or a persistent headache in a person who was previously headache free.[32]

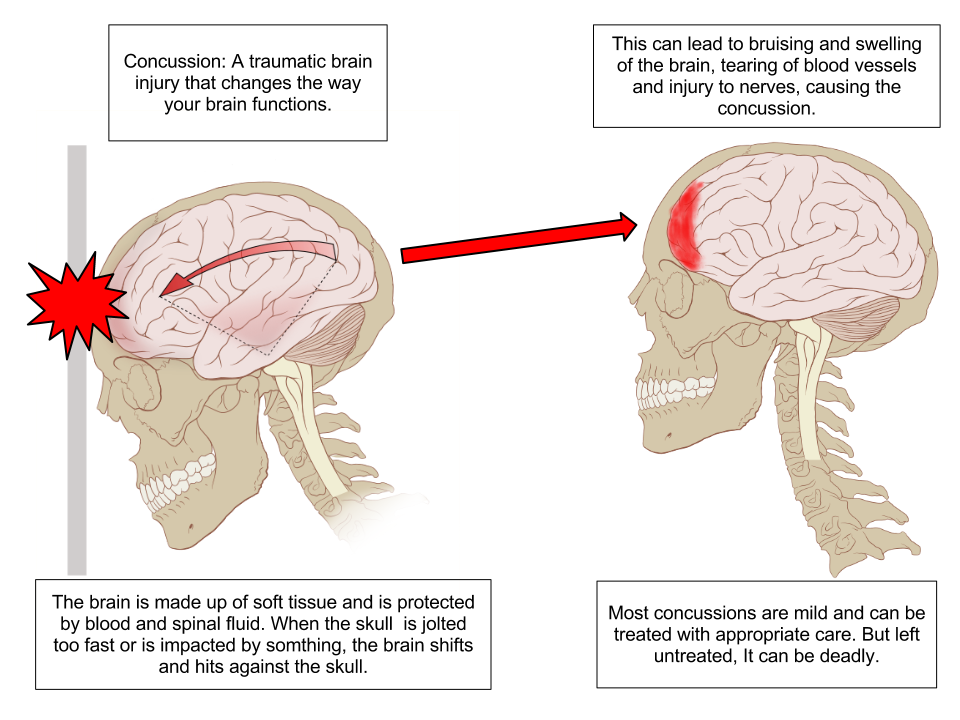

Concussion

A concussion is a type of traumatic brain injury caused by a blow to the head or by a hit to the body that causes the head and brain to move rapidly back and forth. This sudden movement causes the brain to bounce around in the skull, creating chemical changes in the brain and sometimes damaging brain cells.[33] See Figure 7.14[34] for an illustration of a concussion.

Video Review of Concussions[35]

A person who has experienced a concussion may report the following symptoms:

- Headache or “pressure” in head

- Nausea or vomiting

- Balance problems or dizziness or double or blurry vision

- Light or noise sensitivity

- Feeling sluggish, hazy, foggy, or groggy

- Confusion, concentration, or memory problems

- Just not “feeling right” or “feeling down”[36]

The following signs may be observed in someone who has experienced a concussion:

- Can’t recall events prior to or after a hit or fall

- Appears dazed or stunned

- Forgets an instruction, is confused about an assignment or position, or is unsure of the game, score, or opponent

- Moves clumsily

- Answers questions slowly

- Loses consciousness (even briefly)

- Shows mood, behavior, or personality changes[37]

Anyone suspected of experiencing a concussion should immediately be seen by a health care provider or go to the emergency department for further testing.

Concussion Signs and Symptoms

Head Injury

Head and traumatic brain injuries are major causes of immediate death and disability. Falls are the most common cause of head injuries in young children (ages 0–4 years), adolescents (15–19 years), and the elderly (over 65 years). Strong blows to the brain case of the skull can produce fractures resulting in bleeding inside the skull. A blow to the lateral side of the head may fracture the bones of the pterion. If the underlying artery is damaged, bleeding can cause the formation of a hematoma (collection of blood) between the brain and interior of the skull. As blood accumulates, it will put pressure on the brain. Symptoms associated with a hematoma may not be apparent immediately following the injury, but if untreated, blood accumulation will continue to exert increasing pressure on the brain and can result in death within a few hours.[38]

See Figure 7.15[39] for an image of an epidural hematoma indicated by a red arrow associated with a skull fracture.

Sinusitis

Sinusitis is the medical diagnosis for inflamed sinuses that can be caused by a viral or bacterial infection. When the nasal membranes become swollen, the drainage of mucous is blocked and causes pain.

There are several types of sinusitis, including these types:

- Acute Sinusitis: Infection lasting up to 4 weeks

- Chronic Sinusitis: Infection lasting more than 12 weeks

- Recurrent Sinusitis: Several episodes of sinusitis within a year

Symptoms of sinusitis can include fever, weakness, fatigue, cough, and congestion. There may also be mucus drainage in the back of the throat, called postnasal drip. Health care providers diagnose sinusitis based on symptoms and an examination of the nose and face. Treatments include antibiotics, decongestants, and pain relievers.[40]

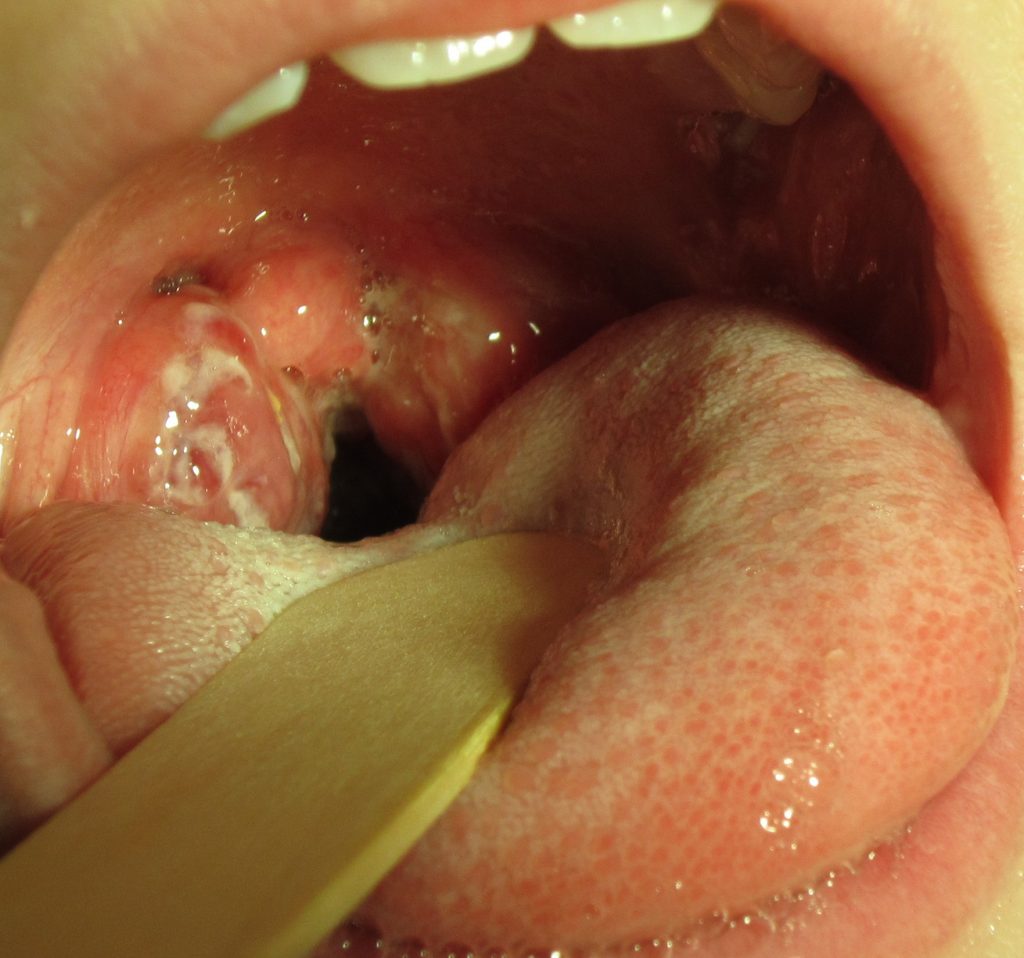

Pharyngitis

Pharyngitis is the medical term used for infection and/or inflammation in the back of the throat (pharynx). Common causes of pharyngitis are the cold viruses, influenza, strep throat caused by group A streptococcus, and mononucleosis. Strep throat typically causes white patches on the tonsils with a fever and enlarged lymph nodes. It must be treated with antibiotics to prevent potential complications in the heart and kidneys. See Figure 7.16[41] for an image of strep throat in a child.

If not diagnosed as strep throat, most cases of pharyngitis are caused by viruses, and the treatment is aimed at managing the symptoms. Nurses can teach patients the following ways to decrease the discomfort of a sore throat:

- Drink soothing liquids such as lemon tea with honey or ice water.

- Gargle several times a day with warm salt water made of 1/2 tsp. of salt in 1 cup of water.

- Suck on hard candies or throat lozenges.

- Use a cool-mist vaporizer or humidifier to moisten the air.

- Try over-the-counter pain medicines, such as acetaminophen.[42]

Epistaxis

Epistaxis, the medical term for a nose bleed, is a common problem affecting up to 60 million Americans each year. Although most cases of epistaxis are minor and manageable with conservative measures, severe cases can become life-threatening if the bleeding cannot be stopped.[43] See Figure 7.17[44] for an image of a severe case of epistaxis.

The most common cause of epistaxis is dry nasal membranes in winter months due to low temperatures and low humidity. Other common causes are picking inside the nose with fingers, trauma, anatomical deformity, high blood pressure, and clotting disorders. Medications associated with epistaxis are aspirin, clopidogrel, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and anticoagulants.[45]

To treat a nose bleed, have the victim lean forward at the waist and pinch the lateral sides of the nose with the thumb and index finger for up to 15 minutes while breathing through the mouth.[46] Continued bleeding despite this intervention requires urgent medical intervention such as nasal packing.

Cleft Lip and Palate

During embryonic development, the right and left maxilla bones come together at the midline to form the upper jaw. At the same time, the muscle and skin overlying these bones join together to form the upper lip. Inside the mouth, the palatine processes of the maxilla bones, along with the horizontal plates of the right and left palatine bones, join together to form the hard palate. If an error occurs in these developmental processes, a birth defect of cleft lip or cleft palate may result.

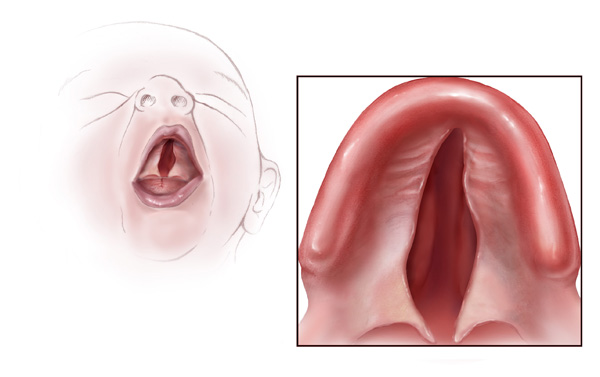

Cleft lip is a common developmental defect that affects approximately 1:1,000 births, most of which are male. This defect involves a partial or complete failure of the right and left portions of the upper lip to fuse together, leaving a cleft (gap). See Figure 7.18[47] for an image of an infant with a cleft lip.

A more severe developmental defect is a cleft palate that affects the hard palate, the bony structure that separates the nasal cavity from the oral cavity. See Figure 7.19[48] for an illustration of a cleft palate. Cleft palate affects approximately 1:2,500 births and is more common in females. It results from a failure of the two halves of the hard palate to completely come together and fuse at the midline, thus leaving a gap between the nasal and oral cavities. In severe cases, the bony gap continues into the anterior upper jaw where the alveolar processes of the maxilla bones also do not properly join together above the front teeth. If this occurs, a cleft lip will also be seen. Because of the communication between the oral and nasal cavities, a cleft palate makes it very difficult for an infant to generate the suckling needed for nursing, thus creating risk for malnutrition. Surgical repair is required to correct a cleft palate.[49]

Poor Oral Health

Despite major improvements in oral health for the population as a whole, oral health disparities continue to exist for many racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups in the United States. Healthy People 2020, a nationwide initiative geared to improve the health of Americans, identified improved oral health as a health care goal. A growing body of evidence has also shown that periodontal disease is associated with negative systemic health consequences. Periodontal diseases are infections and inflammation of the gums and bone that surround and support the teeth. Red, swollen, and bleeding gums are signs of periodontal disease. Other symptoms of periodontal disease include bad breath, loose teeth, and painful chewing.[50] In 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 42% of U.S. adults have some form of periodontitis, and almost 60% of adults aged 65 and older have periodontitis. See Figure 7.20[51] for an image of a patient with periodontal disease. Nurses may encounter patients who complain of bleeding gums, or they may discover other signs of periodontal disease during a physical assessment.

Because many Americans lack access to oral care, it is important for nurses to perform routine oral assessment and identify needs for follow-up. If signs and/or symptoms indicate potential periodontal disease, the patient should be referred to a dental health professional for a more thorough evaluation.[52]

Thrush/Candidiasis

Candidiasis is a fungal infection caused by Candida. Candida normally lives on the skin and inside the body without causing any problems, but it can multiply and cause an infection if the environment inside the mouth, throat, or esophagus changes in a way that encourages fungal growth.[53] See Figure 7.21[54] for an image of candidiasis.

Candidiasis in the mouth and throat can have many symptoms, including the following:

- White patches on the inner cheeks, tongue, roof of the mouth, and throat

- Redness or soreness

- Cotton-like feeling in the mouth

- Loss of taste

- Pain while eating or swallowing

- Cracking and redness at the corners of the mouth[55]

Candidiasis in the mouth or throat is common in babies but is uncommon in healthy adults. Risk factors for getting candidiasis as an adult include the following:

- Wearing dentures

- Diabetes

- Cancer

- HIV/AIDS

- Taking antibiotics or corticosteroids including inhaled corticosteroids for conditions like asthma

- Taking medications that cause dry mouth or have medical conditions that cause dry mouth

- Smoking

The treatment for mild to moderate cases of candidiasis infections in the mouth or throat is typically an antifungal medicine applied to the inside of the mouth for 7 to 14 days, such as clotrimazole, miconazole, or nystatin.

"Meth Mouth"

The use of methamphetamine (i.e., meth), a strong stimulant drug, has become an alarming public health issue in the United States. A common sign of meth abuse is extreme tooth and gum decay often referred to as “Meth Mouth.” See Figure 7.22[56] for an image of Meth Mouth.

Signs of Meth Mouth include the following:

- Dry Mouth. Methamphetamines dry out the salivary glands, and the acid content in the mouth will start to destroy the enamel on the teeth. Eventually this will lead to cavities.

- Cracked Teeth. Methamphetamine can make the user feel anxious, hyper, or nervous, so they clench or grind their teeth. You may see severe wear patterns on their teeth.

- Tooth Decay. Meth users crave beverages high in sugar while they are “high.” The bacteria that feed on the sugars in the mouth will secrete acid, which can lead to more tooth destruction. With meth users, tooth decay will start at the gum line and eventually spread throughout the tooth. The front teeth are usually destroyed first.

- Gum Disease. Methamphetamine users do not seek out regular dental treatment. Lack of oral health care can contribute to periodontal disease. Methamphetamines also cause the blood vessels that supply the oral tissues to shrink in size, reducing blood flow, causing the tissues to break down.

- Lesions. Users who smoke meth present with lesions and/or burns on their lips or gingival inside the cheeks or on the hard palate. Users who snort may present burns in the back of their throats.[57]

Nurses who notice possible signs of Meth Mouth should report their concerns to the health care provider, not only for a referral for dental care, but also for treatment of suspected substance abuse.

Dysphagia

Dysphagia is the medical term for difficulty swallowing that can be caused by many medical conditions. Nurses are often the first health care professionals to notice a patient’s difficulty swallowing as they administer medications or monitor food intake. Early identification of dysphagia, especially after a patient has experienced a cerebrovascular accident (i.e., stroke) or other head injury, helps to prevent aspiration pneumonia.[58] Aspiration pneumonia is a type of lung infection caused by material from the stomach or mouth entering the lungs and can be life-threatening.

Signs of dysphagia include the following:

- Coughing during or right after eating or drinking

- Wet or gurgly sounding voice during or after eating or drinking

- Extra effort or time required to chew or swallow

- Food or liquid leaking from mouth

- Food getting stuck in the mouth

- Difficulty breathing after meals[59]

The Barnes-Jewish Hospital-Stroke Dysphagia Screen (BJH-SDS) is an example of a simple, evidence-based bedside screening tool that can be used by nursing staff to efficiently identify swallowing impairments in patients who have experienced a stroke. See internet resource below for an image of the dysphagia screening tool. The result of the screening test is recorded as a “fail” if any of the five items tested are abnormal (Glasgow Coma Scale < 13, facial/tongue/palatal asymmetry or weakness, or signs of aspiration on the 3-ounce water test) or “pass” if all five items tested were normal. Patients with a failed screening result are placed on nothing-by-mouth (NPO) status until further evaluation is completed by a speech therapist. For more information about using the Glasgow Coma Scale, see the "Assessing Mental Status" subsection in the “Neurological Assessment” chapter.

Enlarged Lymph Nodes

Lymphadenopathy is the medical term for swollen lymph nodes. In a child, a node is considered enlarged if it is more than 1 centimeter (0.4 inch) wide. See Figure 7.23[60] for an image of an enlarged cervical lymph node.

Common infections such as a cold, pharyngitis, sinusitis, mononucleosis, strep throat, ear infection, or infected tooth often cause swollen lymph nodes. However, swollen lymph nodes can also signify more serious conditions. Notify the health care provider if the patient’s lymph nodes have the following characteristics:

- Do not decrease in size after several weeks or continue to get larger

- Are red and tender

- Feel hard, irregular, or fixed in place

- Are associated with night sweats or unexplained weight loss

- Are larger than 1 centimeter in diameter

The health care provider may order blood tests, a chest X-ray, or a biopsy of the lymph node if these signs occur. [61]

Thyroid

The thyroid is a butterfly-shaped gland located at the front of the neck that controls many of the body’s important functions. The thyroid gland makes hormones that affect breathing, heart rate, digestion, and body temperature. If the thyroid makes too much or not enough thyroid hormone, many body systems are affected. In hypothyroidism, the thyroid gland doesn’t produce enough hormone and many body functions slow down. When the thyroid makes too much hormone, a condition called hyperthyroidism, many body systems speed up.[62]

A goiter is an abnormal enlargement of the thyroid gland that can occur with hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism. If you find a goiter when assessing a patient’s neck, notify the health care provider for additional testing and treatment. See Figure 7.24[63] for an image of a goiter.

Subjective Assessment

Begin the head and neck assessment by asking focused interview questions to determine if the patient is currently experiencing any symptoms or has a previous medical history related to head and neck issues.

Table 7.4a Interview Questions for Subjective Assessment of the Head and Neck

| Interview Questions | Follow-up |

|---|---|

| Have you ever been diagnosed with a medical condition related to your head such as headaches, a concussion, a stroke, or a head injury? | Please describe. |

| Have you ever been diagnosed with a medical condition related to your neck such a thyroid or swallowing issue? | Please describe. |

| Are you currently taking any medications, herbs, or supplements for headaches or for your thyroid? | Please describe. |

| Have you had any symptoms such as headaches, nosebleeds, nasal drainage, sinus pressure, sore throat, or swollen lymph nodes? | If yes, use the PQRSTU method to gather additional information regarding each symptom. |

Specific oral assessment questions:[64]

|

Life Span Considerations

Infants and Children

For infants, observe head control and muscle strength. Palpate the skull and fontanelles for smoothness. Ask the parents or guardians if the child has had frequent throat infections or a history of cleft lip or cleft palate. Observe head shape, size, and symmetry.

Older Adults

Ask older adults if they have experienced any difficulties swallowing or chewing. Document if dentures are present. Muscle atrophy and loss of fat often cause neck shortening. Fat accumulation in the back of the neck causes a condition referred to as "Dowager's hump."

Objective Assessment

Use any information obtained during the subjective interview to guide your physical assessment.

Inspection

- Begin by inspecting the head for skin color and symmetry of facial movements, noting any drooping. If drooping is noted, ask the patient to smile, frown, and raise their eyebrows and observe for symmetrical movement. Note the presence of previous injuries or deformities.

- Inspect the nose for patency and note any nasal drainage.

- Inspect the oral cavity and ask the patient to open their mouth and say “Ah.” Inspect the patient's mouth using a good light and tongue blade.

- Note oral health of the teeth and gums.

- If the patient wears dentures, remove them so you can assess the underlying mucosa.

- Assess the oral mucosa for color and the presence of any abnormalities.

- Note the color of the gums, which are normally pink. Inspect the gum margins for swelling, bleeding, or ulceration.

- Inspect the teeth and note any missing, discolored, misshapen, or abnormally positioned teeth. Assess for loose teeth with a gloved thumb and index finger, and document halitosis (bad breath) if present.[65]

- Assess the tongue. It should be midline and with no sores or coatings present.

- Assess the uvula. It should be midline and should rise symmetrically when the patient says “Ah.”

- Is the patient able to swallow their own secretions? If the patient has had a recent stroke or you have any concerns about their ability to swallow, perform a brief bedside swallow study according to agency policy before administering any food, fluids, or medication by mouth.

- Note oral health of the teeth and gums.

- Inspect the neck. The trachea should be midline, and there should not be any noticeable enlargement of lymph nodes or the thyroid gland.

- Note the patient’s speech. They should be able to speak clearly with no slurring or garbled words.

If any neurological concerns are present, a cranial nerve assessment may be performed. Read more about a cranial nerve assessment in the “Neurological Assessment” chapter.

Auscultation

Auscultation is not typically performed by registered nurses during a routine neck assessment. However, advanced practice nurses and other health care providers may auscultate the carotid arteries for the presence of a swishing sound called a bruit.

Palpation

Palpate the neck for masses and tenderness. Lymph nodes, if palpable, should be round and movable and should not be enlarged or tender. See the figure illustrating the location of lymph nodes in the head and neck in the "Head and Neck Basic Concepts" section earlier in this chapter. Advanced practice nurses and other health care providers palpate the thyroid for enlargement, further evaluate lymph nodes, and assess the presence of any masses.

See Table 7.4b for a comparison of expected versus unexpected findings when assessing the head and neck.

Table 7.4b Expected Versus Unexpected Findings on Adult Assessment of the Head and Neck

| Assessment | Expected Findings | Unexpected Findings (to document and notify provider if new finding*) |

|---|---|---|

| Inspection | Skin tone is appropriate for ethnicity, and skin is dry.

Facial movements are symmetrical. Nares are patent and no drainage is present. Uvula and tongue are midline. Teeth and gums are in good condition. Patient is able to swallow their own secretions. Trachea is midline. If dentures are present, there is a good fit, and the patient is able to appropriately chew food. |

Skin is pale, cyanotic, or diaphoretic (inappropriately perspiring).

New asymmetrical facial expressions or drooping is present. Nares are occluded or nasal drainage is present. Uvula and/or tongue is deviated to one side. White coating or lesions on the tongue or buccal membranes (inner cheeks) are present. Teeth are missing or decay is present that impacts the patient’s ability to chew. After swallowing, the patient coughs, drools, chokes, or speaks in a gurgly/wet voice. Trachea is deviated to one side. Dentures have poor fit and/or the patient is unable to chew food contained in a routine diet. |

| Palpation | No unusual findings regarding lymph nodes is present. | Cervical lymph nodes are enlarged, tender, or nonmovable. Report any concerns about lymph nodes to the health care provider. |

| *CRITICAL CONDITIONS to report immediately | New asymmetry of facial expressions, tracheal deviation to one side, slurred or garbled speech, signs of impaired swallowing, coughing during or after swallowing, or a “wet” voice after swallowing. |

Video Review of Head and Neck Assessment[66]

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities'" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

1. You are working as a triage nurse in a primary care clinic. You just received a phone call from a young woman who is complaining of significant discomfort related to newly diagnosed strep throat. What instructions can you provide to her to aid in symptom management in order to alleviate discomfort?

2. You are assessing a patient's head and neck and note the following findings. Which should be reported to the health care provider?

- Tongue is midline

- White patches noted on both tonsils

- Uvula raises when patient says "Ahhh"

- Speech is slurred

- Thyroid enlarged

Learning Activities

(Answers to "Learning Activities'" can be found in the "Answer Key" at the end of the book. Answers to interactive activity elements will be provided within the element as immediate feedback.)

1. You are working as a triage nurse in a primary care clinic. You just received a phone call from a young woman who is complaining of significant discomfort related to newly diagnosed strep throat. What instructions can you provide to her to aid in symptom management in order to alleviate discomfort?

2. You are assessing a patient's head and neck and note the following findings. Which should be reported to the health care provider?

- Tongue is midline

- White patches noted on both tonsils

- Uvula raises when patient says "Ahhh"

- Speech is slurred

- Thyroid enlarged