11.2 Basic Concepts of Oxygenation

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

When assessing a patient’s oxygenation status, it is important for the nurse to have an understanding of the underlying structures of the respiratory system to best understand their assessment findings. Visit the “Respiratory Assessment” chapter for more information about the structures of the respiratory system.

Video Review for Oxygenation Basics

View the TED-Ed Oxygen’s Journey video on YouTube[1]

Breathing Mechanics[2]

Gas Exchange[3]

Carbon Dioxide Transport[4]

Assessing Oxygenation Status

A patient’s oxygenation status is routinely assessed using pulse oximetry, referred to as SpO2. SpO2 is an estimated oxygenation level based on the saturation of hemoglobin measured by a pulse oximeter. Because the majority of oxygen carried in the blood is attached to hemoglobin within the red blood cell, SpO2 estimates how much hemoglobin is “saturated” with oxygen. The target range of SpO2 for an adult is 94-98%.[5] For patients with chronic respiratory conditions, such as COPD, the target range for SpO2 is often lower at 88% to 92%. Although SpO2 is an efficient, noninvasive method to assess a patient’s oxygenation status, it is an estimate and not always accurate. For example, if a patient is severely anemic and has a decreased level of hemoglobin in the blood, the SpO2 reading is affected. Decreased peripheral circulation can also cause a misleading low SpO2 level.

A more specific measurement of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood is obtained through an arterial blood gas (ABG). ABG results are often obtained for patients who have deteriorating or unstable respiratory status requiring urgent and emergency treatment. An ABG is a blood sample that is typically drawn from the radial artery by a respiratory therapist, emergency or critical care nurse, or health care provider. ABG results evaluate oxygen, carbon dioxide, pH, and bicarbonate levels. The partial pressure of oxygen in the blood is referred to as PaO2. The normal PaO2 level of a healthy adult is 80 to 100 mmHg. The PaO2 reading is more accurate than a SpO2 reading because it is not affected by hemoglobin levels. The PaCO2 level is the partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the blood. The normal PaCO2 level of a healthy adult is 35-45 mmHg. The normal range of pH level for arterial blood is 7.35-7.45, and the normal range for the bicarbonate (HCO3) level is 22-26. The SaO2 level is also obtained, which is the calculated arterial oxygen saturation level. See Table 11.2a for a summary of normal ranges of ABG values.[6]

Table 11.2a Normal Ranges of ABG Values

| Value | Description | Normal Range |

|---|---|---|

| pH | Acid-base balance of blood | 7.35-7.45 |

| PaO2 | Partial pressure of oxygen | 80-100 mmHg |

| PaCO2 | Partial pressure of carbon dioxide | 35-45 mmHg |

| HCO3 | Bicarbonate level | 22-26 mEq/L |

| SaO2 | Calculated oxygen saturation | 95-100% |

Hypoxia and Hypercapnia

Hypoxia is defined as a reduced level of tissue oxygenation. Hypoxia has many causes, ranging from respiratory and cardiac conditions to anemia. Hypoxemia is a specific type of hypoxia that is defined as decreased partial pressure of oxygen in the blood (PaO2), measured by an arterial blood gas (ABG).

Early signs of hypoxia are anxiety, confusion, and restlessness. As hypoxia worsens, the patient’s level of consciousness and vital signs will worsen, with increased respiratory rate and heart rate and decreased pulse oximetry readings. Late signs of hypoxia include bluish discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes called cyanosis. Cyanosis is most easily seen around the lips and in the oral mucosa. A sign of chronic hypoxia is clubbing, a gradual enlargement of the fingertips (see Figure 11.1[7]). See Table 11.2b for symptoms and signs of hypoxia.[8]

Hypercapnia is an elevated level of carbon dioxide in the blood. This level is measured by the PaCO2 level in an ABG test and is indicated when the PaCO2 level is higher than 45. Hypercapnia is typically caused by hypoventilation or areas of the alveoli that are ventilated but not perfused. In a state of hypercapnia or hypoventilation, there is an accumulation of carbon dioxide in the blood. The increased carbon dioxide causes the pH of the blood to drop, leading to a state of respiratory acidosis. You can read more about respiratory acidosis in the “Fluids and Electrolytes” chapter of the Open RN Nursing Fundamentals book. Patients with hypercapnia can present with tachycardia, dyspnea, flushed skin, confusion, headaches, and dizziness. If the hypercapnia develops gradually over time, such as in a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), symptoms may be mild or may not be present at all. Hypercapnia is managed by addressing its underlying cause. A noninvasive positive pressure device such as a BiPAP may provide support to patients who are having trouble breathing normally, but if this is not sufficient, intubation may be required.[9]

Table 11.2b Symptoms and Signs of Hypoxia

| Signs & Symptoms | Description |

|---|---|

| Restlessness | Patient may become increasingly fidgety, move about the bed, demonstrate signs of anxiety and agitation. Restlessness is an early sign of hypoxia. |

| Tachycardia | An elevated heart rate (above 100 beats per minute in adults) can be an early sign of hypoxia. |

| Tachypnea | An increased respiration rate (above 20 breaths per minute in adults) is an indication of respiratory distress. |

| Shortness of breath (Dyspnea) | Shortness of breath is a subjective symptom of not getting enough air. Depending on severity, dyspnea causes increased levels of anxiety. |

| Oxygen saturation level (SpO2) | Oxygen saturation levels should be above 94% for an adult without an underlying respiratory condition. |

| Use of accessory muscles | Use of neck or intercostal muscles when breathing is an indication of respiratory distress. |

| Noisy breathing | Audible noises with breathing are an indication of respiratory conditions. Assess lung sounds with a stethoscope for adventitious sounds such as wheezing, rales, or crackles. Secretions can plug the airway, thereby decreasing the amount of oxygen available for gas exchange in the lungs. |

| Flaring of nostrils or pursed lip breathing | Flaring is a sign of hypoxia, especially in infants. Pursed-lip breathing is a technique often used in patients with COPD. This breathing technique increases the amount of carbon dioxide exhaled so that more oxygen can be inhaled. |

| Position of patient | Patients in respiratory distress may sit up or lean over by resting arms on their legs to enhance lung expansion. Patients who are hypoxic may not be able to lie flat in bed. |

| Ability of patient to speak in full sentences | Patients in respiratory distress may be unable to speak in full sentences or may need to catch their breath between sentences. |

| Skin color (Cyanosis) | Changes in skin color to bluish or gray are a late sign of hypoxia. |

| Confusion or loss of consciousness (LOC) | This is a worsening sign of hypoxia. |

| Clubbing | Clubbing, a gradual enlargement of the fingertips, is a sign of chronic hypoxia. |

Treating Hypoxia

Acute hypoxia is a medical emergency and should be treated promptly with oxygen therapy. Failure to initiate oxygen therapy when needed can result in serious harm or death of the patient. Although oxygen is considered a medication that requires a prescription, oxygen therapy may be initiated without a physician’s order in emergency situations as part of the nurse’s response to the “ABCs,” a common abbreviation for airway, breathing, and circulation. Most agencies have a protocol in place that allows nurses to apply oxygen in emergency situations. After applying oxygen as needed, the nurse then contacts the provider, respiratory therapist, or rapid response team, depending on the severity of hypoxia. Devices such high flow oxymasks, CPAP, BiPAP, or mechanical ventilation may be initiated by the respiratory therapist or provider to deliver higher amounts of inspired oxygen. Various types of oxygenation devices are further explained in the “Oxygenation Equipment” section.

Prescription orders for oxygen therapy will include two measurements of oxygen to be delivered – the oxygen flow rate and the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2). The oxygen flow rate is the number dialed up on the oxygen flow meter between 1 L/minute and 15 L/minute. Fio2 is the concentration of oxygen the patient inhales. Room air contains 21% oxygen concentration, so the FiO2 for supplementary oxygen therapy will range from 21% to 100% concentration.

In addition to administering oxygen therapy, there are several other interventions the nurse should consider implementing to a hypoxic patient. Additional interventions used to treat hypoxia in conjunction with oxygen therapy are outlined in Table 11.2c.[10]

Table 11.2c Interventions to Manage Hypoxia

| Interventions | Additional Information |

|---|---|

| Raise the Head of the Bed | Raising the head of the bed to high Fowler’s position promotes effective chest expansion and diaphragmatic descent, maximizes inhalation, and decreases the work of breathing. Patients with COPD who are short of breath may gain relief by sitting upright or leaning over a bedside table while in bed. |

| Encourage Enhanced Breathing and Coughing Techniques | Enhanced breathing and coughing techniques such as using pursed-lip breathing, coughing and deep breathing, huffing technique, incentive spirometry, and flutter valves may assist patients to clear their airway while maintaining their oxygen levels. See the following “Enhanced Breathing and Coughing Techniques” section for additional information regarding these techniques. |

| Manage Oxygen Therapy and Equipment | If the patient is already on supplemental oxygen, ensure the equipment is turned on, set at the required flow rate, correctly positioned on the patient, and properly connected to an oxygen supply source. If a portable tank is being used, check the oxygen level in the tank. Ensure the connecting oxygen tubing is not kinked, which could obstruct the flow of oxygen. Feel for the flow of oxygen from the exit ports on the oxygen equipment. In hospitals where medical air and oxygen are used, ensure the patient is connected to the oxygen flow port. Hospitals in America follow the national standard that oxygen flow ports are green and air outlets are yellow. |

| Assess the Need for Respiratory Medications | Pharmacological management is essential for patients with respiratory disease such as asthma, COPD, or severe allergic response. Bronchodilators effectively relax smooth muscles and open airways. Glucocorticoids relieve inflammation and also assist in opening air passages. Mucolytics decrease the thickness of pulmonary secretions so that they can be expectorated more easily. |

| Provide Oral Suctioning if Needed | Some patients may have a weakened cough that inhibits their ability to clear secretions from the mouth and throat. Patients with muscle disorders or those who have experienced a cerebral vascular accident (CVA) are at risk for aspiration pneumonia, which is caused by the accidental inhalation of material from the mouth or stomach. Provide oral suction if the patient is unable to clear secretions from the mouth and pharynx. See the chapter on “Tracheostomy Care and Suctioning” for additional details on suctioning. |

| Provide Pain Relief If Needed | Provide adequate pain relief if the patient is reporting pain. Pain increases anxiety and may inhibit the patient’s ability to take in full breaths. |

| Consider the Side Effects of Pain Medications | A common side effect of pain medication is sedation and respiratory depression. For more information about interventions to manage respiratory depression, see the “Oxygenation” chapter in the Open RN Nursing Fundamentals textbook. |

| Consider Other Devices to Enhance Clearance of Secretions | Chest physiotherapy and specialized devices assist with secretion clearance, such as handheld flutter valves or vests that inflate and vibrate the chest wall. Consider requesting a consultation with a respiratory therapist based on the patient’s situation. |

| Plan Frequent Rest Periods Between Activities | Patients experiencing hypoxia often feel short of breath and fatigue easily. Allow the patient to rest frequently, and space out interventions to decrease oxygen demand in patients whose reserves are likely limited. |

| Consider Other Potential Causes of Dyspnea | If a patient’s level of dyspnea is worsening, assess for other underlying causes in addition to the primary diagnosis. Are there other respiratory, cardiovascular, or hematological conditions such as anemia occurring? Start by reviewing the patient’s most recent hemoglobin and hematocrit lab results. Completing a thorough assessment may reveal abnormalities in these systems to report to the health care provider. |

| Consider Obstructive Sleep Apnea | Patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) are often not previously diagnosed prior to hospitalization. The nurse may notice the patient snores, has pauses in breathing while snoring, or awakens not feeling rested. These signs may indicate the patient is unable to maintain an open airway while sleeping, resulting in periods of apnea and hypoxia. If these apneic periods are noticed but have not been previously documented, the nurse should report these findings to the health care provider for further testing and follow-up. Testing consists of using continuous pulse oximetry while the patient is sleeping to determine if the patient is hypoxic during these episodes and if a CPAP device should be prescribed. See the box below for additional information regarding OSA. |

| Anxiety | Anxiety often accompanies the feeling of dyspnea and can worsen it. Anxiety in patients with COPD is chronically undertreated. It is important for the nurse to address the feelings of anxiety and dyspnea. Anxiety can be relieved by teaching enhanced breathing and coughing techniques, encouraging relaxation techniques, or administering antianxiety medications. |

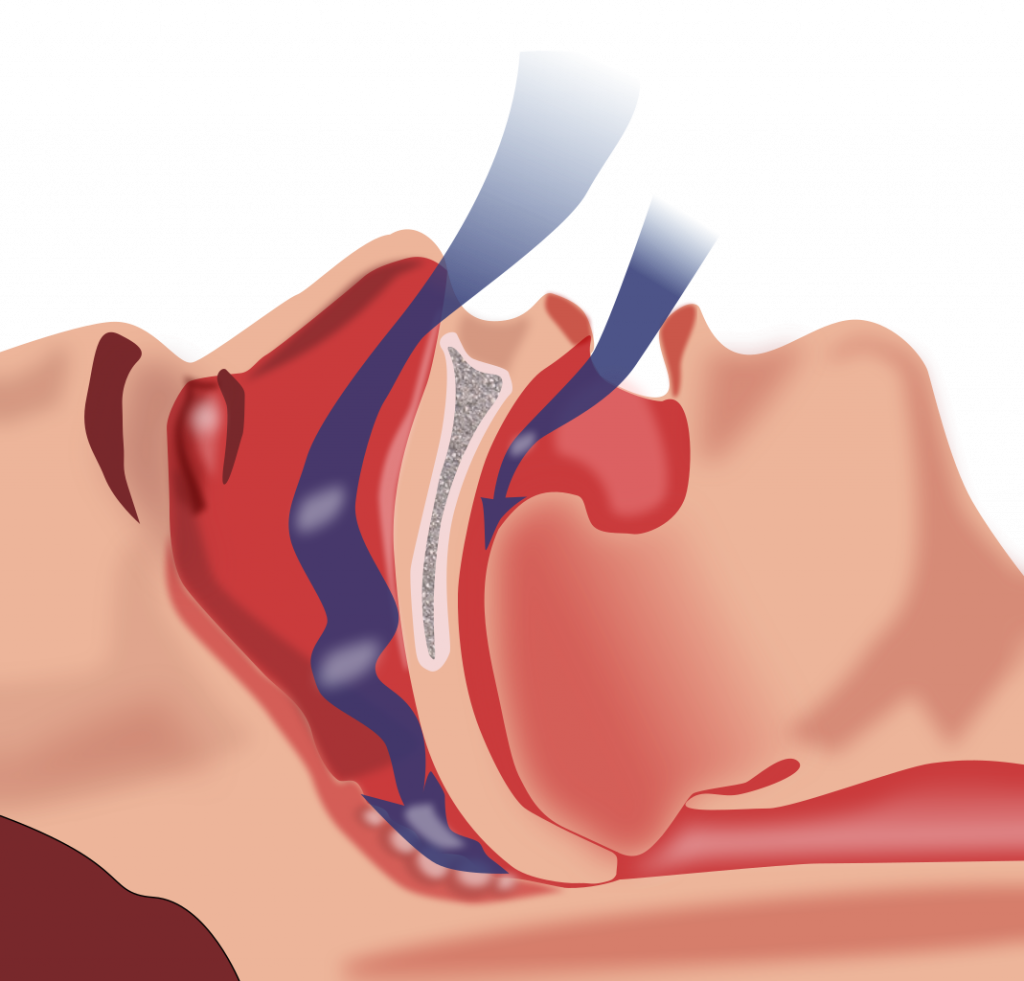

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) is the most common type of sleep apnea. See Figure 11.2[11] for an illustration of OSA. As soft tissue falls to the back of the throat, it impedes the passage of air (blue arrows) through the trachea and is characterized by repeated episodes of complete or partial obstructions of the upper airway during sleep. The episodes of breathing cessations are called “apneas,” meaning “without breath.” Despite the effort to breathe, apneas are associated with a reduction in blood oxygen saturation due to the obstruction of the airway. Treatment for OSA often includes the use of a CPAP device.

Enhanced Breathing and Coughing Techniques

In addition to oxygen therapy and the interventions listed in Table 11.2c to implement for a patient experiencing dyspnea and hypoxia, there are several techniques a nurse can teach a patient to use to enhance their breathing and coughing. These techniques include pursed-lip breathing, incentive spirometry, coughing and deep breathing, and the huffing technique.

Pursed-Lip Breathing

Pursed-lip breathing is a technique that allows people to control their oxygenation and ventilation. The technique requires a person to inspire through the nose and exhale through the mouth at a slow controlled flow. See Figure 11.3[12] for an illustration of pursed-lip breathing. This type of exhalation gives the person a puckered or pursed appearance. By prolonging the expiratory phase of respiration, a small amount of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is created in the airways that helps to keep them open so that more air can be exhaled, thus reducing air trapping that occurs in some conditions such as COPD. Pursed-lip breathing often relieves the feeling of shortness of breath, decreases the work of breathing, and improves gas exchange. People also regain a sense of control over their breathing while simultaneously increasing their relaxation.[13]

View the COPD Foundation’s YouTube video to learn more about pursed-lip breathing:

Breathing Techniques[14]

Incentive Spirometry

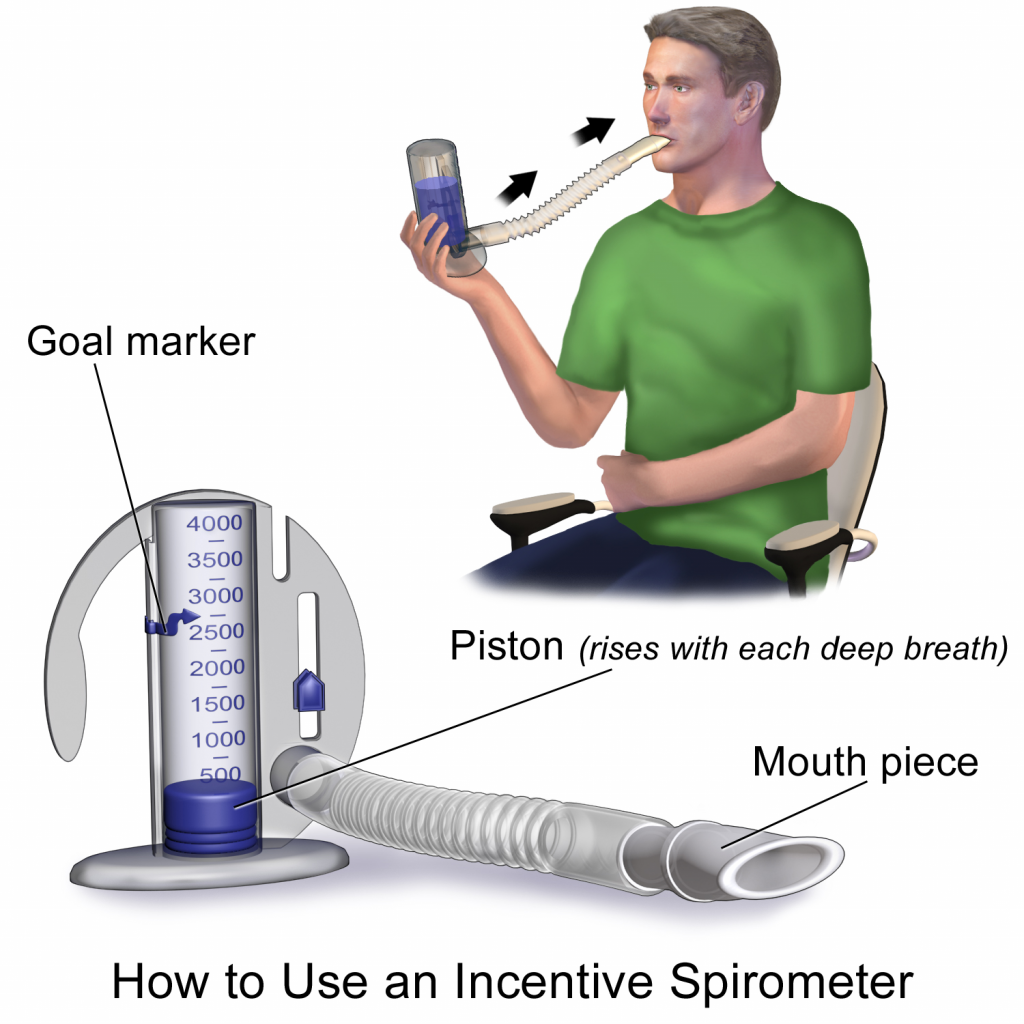

An incentive spirometer is a medical device often prescribed after surgery to prevent and treat atelectasis. Atelectasis occurs when alveoli become deflated or filled with fluid and can lead to pneumonia. See Figure 11.4[15] for an image of a patient using an incentive spirometer. While sitting upright, the patient should breathe in slowly and deeply through the tubing with the goal of raising the piston to a specified level. The patient should attempt to hold their breath for 5 seconds, or as long as tolerated, and then rest for a few seconds. This technique should be repeated by the patient 10 times every hour while awake.[16] The nurse may delegate this intervention to unlicensed assistive personnel, but the frequency in which it is completed and the volume achieved should be documented and monitored by the nurse.

Coughing and Deep Breathing

Teaching the coughing and deep breathing technique is similar to incentive spirometry but no device is required. The patient is encouraged to take deep, slow breaths and then exhale slowly. After each set of breaths, the patient should cough. This technique is repeated 3 to 5 times every hour.

Huffing Technique

The huffing technique is helpful for patients who have difficulty coughing. Teach the patient to inhale with a medium-sized breath and then make a sound like “Ha” to push the air out quickly with the mouth slightly open.

Vibratory PEP Therapy

Vibratory Positive Expiratory Pressure (PEP) therapy uses handheld devices such as “flutter valves” or “Acapella” devices for patients who need assistance in clearing mucus from their airways. These devices (see Figure 11.5[17]) require a prescription and are used in collaboration with a respiratory therapist or advanced health care provider. To use Vibratory PEP therapy, the patient should sit up, take a deep breath, and blow into the device. A flutter valve within the device creates vibrations that help break up the mucus so the patient can cough it up and spit it out. Additionally, a small amount of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) is created in the airways that helps to keep them open so that more air can be exhaled.

Visit NHS University Hospitals Plymouth Physiotherapy’s “Acapella” video on YouTube to review using a flutter valve device[18]

- TED-Ed. (2017, April 13). Oxygen’s surprisingly complex journey through your body - Edna Butler. [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/GVU_zANtroE ↵

- Forciea, B. (2015, May 12). Anatomy and physiology: Respiratory system: Breathing mechanics (v2.0). [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Video used with permission. https://youtu.be/X-J5Xgg3l6s ↵

- Forciea, B. (2015, May 12). Respiratory system: Gas exchange (v2.0). [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Video used with permission. https://youtu.be/uVWko7_v7MM ↵

- Forciea, B. (2015, May 12). Respiratory system: C02 transport (v2.0). [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Video used with permission. https://youtu.be/BmrvqZoxHYI ↵

- Hill, B., & Annesley, S. H. (2020). Monitoring respiratory rate in adults. British Journal of Nursing, 29(1), 12–16. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2020.29.1.12 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Acopaquia.jpg” by Desherinka is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Patel, Miao, Yetiskul, and Majmundar and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of Clinical Procedures for Safer Patient Care by British Columbia Institute of Technology and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Obstruction ventilation apnée sommeil.svg” by Habib M’henni is in the Public Domain ↵

- This work is derivative of "aid611002-v4-728px-Live-With-Chronic-Obstructive-Pulmonary-Disease-Step-8.jpg" by unknown and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0. Access for free at https://www.wikihow.com/Live-With-Chronic-Obstructive-Pulmonary-Disease. ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Nguyen and Duong and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- COPD Foundation. (2020, April 17). Breathing techniques. [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/ZJPJjZRHmy8 ↵

- “Incentive Spirometer.pngsommeil.svg” by BruceBlaus is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2018, May 2). Incentive spirometer. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/4302-incentive-spirometer ↵

- "Flutter Valve Breathing Device 3I3A0982.jpg" by Deanna Hoyord, Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- NHS University Hospitals Plymouth Physiotherapy. (2015, May 12). Acapella. [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/XOvonQVCE6Y ↵

15-15 Rule: A rule in an agency’s hypoglycemia protocols that includes providing 15 grams of carbohydrate, then repeating the blood glucose reading in 15 minutes, and then repeating as needed until the patient’s blood glucose reading is above 70.

Hyperglycemia: Elevated blood glucose reading with associated signs and symptoms such as frequent urination and increased thirst.

Hypoglycemia: A blood glucose reading less than 70 associated with symptoms such as irritability, shakiness, hunger, weakness, or confusion. If not rapidly treated, hypoglycemia can cause seizures and a coma.

Ketoacidosis: A life-threatening complication of hyperglycemia that can occur in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus that is associated with symptoms such as fruity-smelling breath, nausea, vomiting, severe thirst, and shortness of breath.

Oropharynx: The part of the throat at the back of the mouth behind the oral cavity. It includes the back third of the tongue, the soft palate, the side and back walls of the throat, and the tonsils.

Standardized sliding-scale insulin protocol: Standardized instructions for administration of adjustable insulin dosages based on a patient’s premeal blood glucose readings.

Learning Objectives

- Assess tissue condition, wounds, drainage, and pressure injuries

- Cleanse and irrigate wounds

- Apply a variety of wound dressings

- Obtain a wound culture specimen

- Use appropriate aseptic or sterile technique

- Explain procedure to patient

- Adapt procedures to reflect variations across the life span

- Recognize and report significant deviations in wounds

- Document actions and observations

Wound healing is a complex physiological process that restores function to skin and tissue that have been injured. The healing process is affected by several external and internal factors that either promote or inhibit healing. When providing wound care to patients, nurses, in collaboration with other members of the health care team, assess and manage external and internal factors to provide an optimal healing environment.[1]

Complex wounds often require care by specialists. Certified wound care nurses assess, treat, and create care plans for patients with complex wounds, ostomies, and incontinence conditions. They act as educators and consultants to staff nurses and other healthcare professionals. This chapter will discuss wound care basics for entry-level nurses. Request a consultation by a certified wound care nurse when caring for patients with complex or nonhealing wounds.

Airborne precautions: Infection prevention and control interventions to be used in addition to standard precautions for diseases spread by airborne transmission, such as measles and tuberculosis.

Asepsis: A state of being free of disease-causing microorganisms.

Aseptic non-touch technique: A standardized technique, supported by evidence, to maintain asepsis and standardize practice.

Aseptic technique (medical asepsis): The purposeful reduction of pathogen numbers while preventing microorganism transfer from one person or object to another. This technique is commonly used to perform invasive procedures, such as IV starts or urinary catheterization.

Contact precautions: Infection prevention and control interventions to be used in addition to standard precautions for diseases spread by contact with the patient, their body fluids, or their surroundings, such as C-diff, MRSA, VRE, and RSV.

Doff: To take off or remove personal protective equipment, such as gloves or a gown.

Don: To put on equipment for personal protection, such as gloves or a gown.

Droplet precautions: Infection prevention and control interventions to be used in addition to standard precautions; used for diseases spread by large respiratory droplets such as influenza, COVID-19, or pertussis.

Five moments of hand hygiene: Hand hygiene should be performed during the five moments of patient care: immediately before touching a patient; before performing an aseptic task or handling invasive devices; before moving from a soiled body site to a clean body site on a patient; after touching a patient or their immediate environment; after contact with blood, body fluids, or contaminated surfaces (with or without glove use); and immediately after glove removal.

Hand hygiene: A way of cleaning one’s hands to substantially reduce the number of pathogens and other contaminants (e.g., dirt, body fluids, chemicals, or other unwanted substances) to prevent disease transmission or integumentary harm, typically using soap, water, and friction. An alcohol-based hand rub solution may be appropriate hand hygiene for hands not visibly soiled.

Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs): Unintended infections caused by care received in a health care setting.

Key part: Any sterile part of equipment used during an aseptic procedure, such as needle hubs, syringe tips, dressings, etc.

Key site: The site contacted during an aseptic procedure, such as nonintact skin, a potential insertion site, or an access site used for medical devices connected to the patients. Examples of key sites include the insertion or access site for intravenous (IV) devices, urinary catheters, and open wounds.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Personal protective equipment, such as gloves, gowns, face shields, goggles, and masks, used to prevent transmission of disease from patient to patient, patient to health care provider, and health care provider to patient.

Standard precautions: The minimum infection prevention practices that apply to all patient care, regardless of suspected or confirmed infection status of the patient, in any setting where health care is delivered.

Sterile technique (surgical asepsis): Techniques used to eliminate every potential microorganism in and around a sterile field while maintaining objects and areas as free from microorganisms as possible. This technique is the standard of care for surgical procedures, invasive wound management, and central line care.

Headache

A headache is a common type of pain that patients experience in everyday life and a major reason for missed time at work or school. Headaches range greatly in severity of pain and frequency of occurrence. For example, some patients experience mild headaches once or twice a year, whereas others experience disabling migraine headaches more than 15 days a month. Severe headaches such as migraines may be accompanied by symptoms of nausea or increased sensitivity to noise or light. Primary headaches occur independently and are not caused by another medical condition. Migraine, cluster, and tension-type headaches are types of primary headaches. Secondary headaches are symptoms of another health disorder that causes pain-sensitive nerve endings to be pressed on or pulled out of place. They may result from underlying conditions including fever, infection, medication overuse, stress or emotional conflict, high blood pressure, psychiatric disorders, head injury or trauma, stroke, tumors, and nerve disorders such as trigeminal neuralgia, a chronic pain condition that typically affects the trigeminal nerve on one side of the cheek.[2]

Not all headaches require medical attention, but some types of headaches can signify a serious disorder and require prompt medical care. Symptoms of headaches that require immediate medical attention include a sudden, severe headache unlike any the patient has ever had; a sudden headache associated with a stiff neck; a headache associated with convulsions, confusion, or loss of consciousness; a headache following a blow to the head; or a persistent headache in a person who was previously headache free.[3]

Concussion

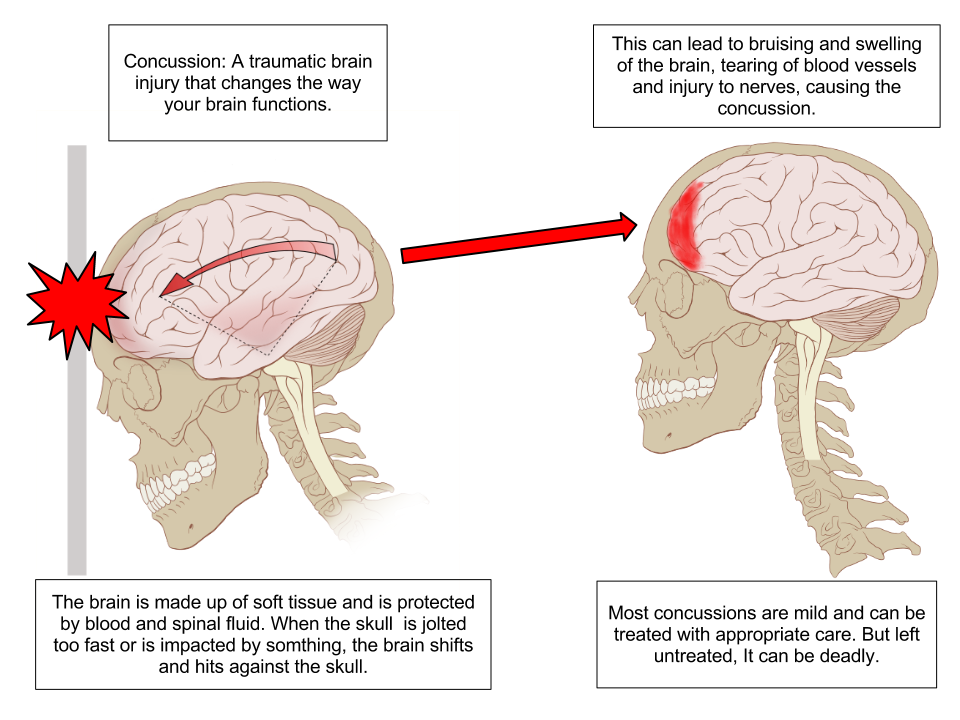

A concussion is a type of traumatic brain injury caused by a blow to the head or by a hit to the body that causes the head and brain to move rapidly back and forth. This sudden movement causes the brain to bounce around in the skull, creating chemical changes in the brain and sometimes damaging brain cells.[4] See Figure 7.14[5] for an illustration of a concussion.

Video Review of Concussions[6]

A person who has experienced a concussion may report the following symptoms:

- Headache or “pressure” in head

- Nausea or vomiting

- Balance problems or dizziness or double or blurry vision

- Light or noise sensitivity

- Feeling sluggish, hazy, foggy, or groggy

- Confusion, concentration, or memory problems

- Just not “feeling right” or “feeling down”[7]

The following signs may be observed in someone who has experienced a concussion:

- Can’t recall events prior to or after a hit or fall

- Appears dazed or stunned

- Forgets an instruction, is confused about an assignment or position, or is unsure of the game, score, or opponent

- Moves clumsily

- Answers questions slowly

- Loses consciousness (even briefly)

- Shows mood, behavior, or personality changes[8]

Anyone suspected of experiencing a concussion should immediately be seen by a health care provider or go to the emergency department for further testing.

Concussion Signs and Symptoms

Head Injury

Head and traumatic brain injuries are major causes of immediate death and disability. Falls are the most common cause of head injuries in young children (ages 0–4 years), adolescents (15–19 years), and the elderly (over 65 years). Strong blows to the brain case of the skull can produce fractures resulting in bleeding inside the skull. A blow to the lateral side of the head may fracture the bones of the pterion. If the underlying artery is damaged, bleeding can cause the formation of a hematoma (collection of blood) between the brain and interior of the skull. As blood accumulates, it will put pressure on the brain. Symptoms associated with a hematoma may not be apparent immediately following the injury, but if untreated, blood accumulation will continue to exert increasing pressure on the brain and can result in death within a few hours.[9]

See Figure 7.15[10] for an image of an epidural hematoma indicated by a red arrow associated with a skull fracture.

Sinusitis

Sinusitis is the medical diagnosis for inflamed sinuses that can be caused by a viral or bacterial infection. When the nasal membranes become swollen, the drainage of mucous is blocked and causes pain.

There are several types of sinusitis, including these types:

- Acute Sinusitis: Infection lasting up to 4 weeks

- Chronic Sinusitis: Infection lasting more than 12 weeks

- Recurrent Sinusitis: Several episodes of sinusitis within a year

Symptoms of sinusitis can include fever, weakness, fatigue, cough, and congestion. There may also be mucus drainage in the back of the throat, called postnasal drip. Health care providers diagnose sinusitis based on symptoms and an examination of the nose and face. Treatments include antibiotics, decongestants, and pain relievers.[11]

Pharyngitis

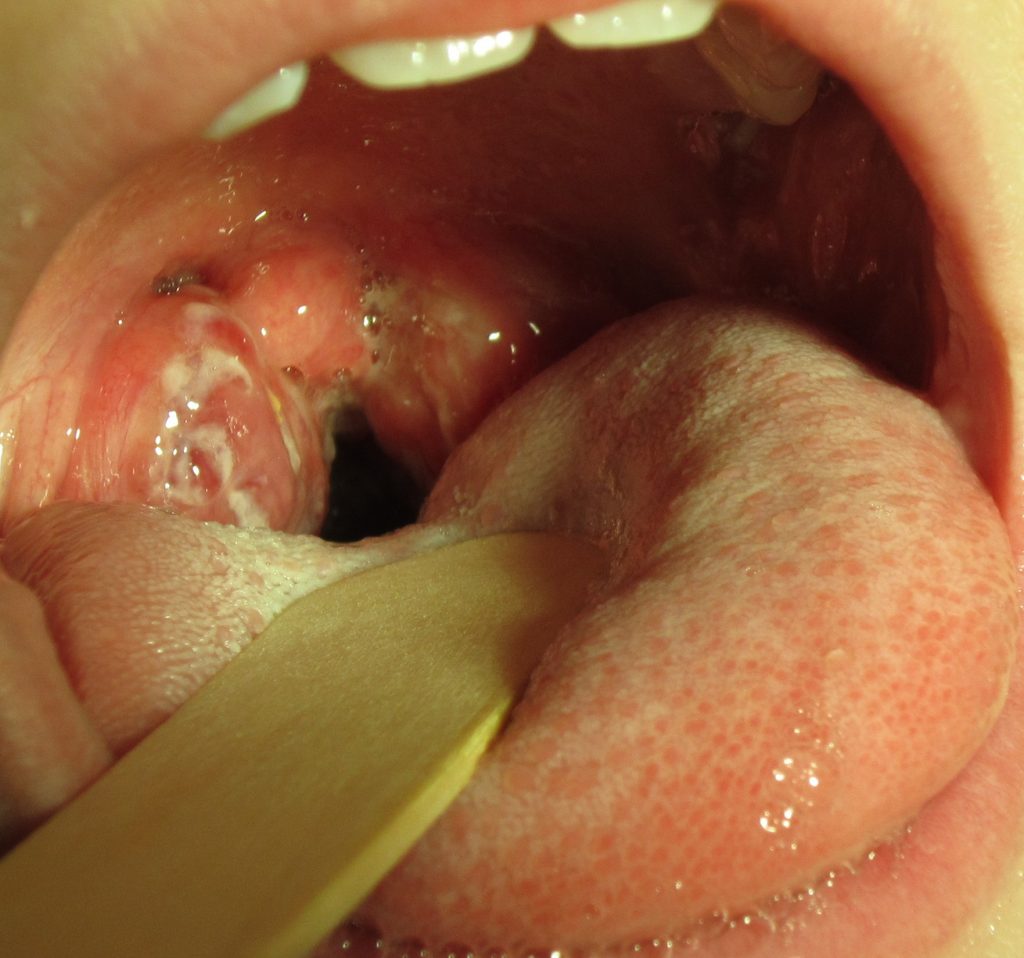

Pharyngitis is the medical term used for infection and/or inflammation in the back of the throat (pharynx). Common causes of pharyngitis are the cold viruses, influenza, strep throat caused by group A streptococcus, and mononucleosis. Strep throat typically causes white patches on the tonsils with a fever and enlarged lymph nodes. It must be treated with antibiotics to prevent potential complications in the heart and kidneys. See Figure 7.16[12] for an image of strep throat in a child.

If not diagnosed as strep throat, most cases of pharyngitis are caused by viruses, and the treatment is aimed at managing the symptoms. Nurses can teach patients the following ways to decrease the discomfort of a sore throat:

- Drink soothing liquids such as lemon tea with honey or ice water.

- Gargle several times a day with warm salt water made of 1/2 tsp. of salt in 1 cup of water.

- Suck on hard candies or throat lozenges.

- Use a cool-mist vaporizer or humidifier to moisten the air.

- Try over-the-counter pain medicines, such as acetaminophen.[13]

Epistaxis

Epistaxis, the medical term for a nose bleed, is a common problem affecting up to 60 million Americans each year. Although most cases of epistaxis are minor and manageable with conservative measures, severe cases can become life-threatening if the bleeding cannot be stopped.[14] See Figure 7.17[15] for an image of a severe case of epistaxis.

The most common cause of epistaxis is dry nasal membranes in winter months due to low temperatures and low humidity. Other common causes are picking inside the nose with fingers, trauma, anatomical deformity, high blood pressure, and clotting disorders. Medications associated with epistaxis are aspirin, clopidogrel, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and anticoagulants.[16]

To treat a nose bleed, have the victim lean forward at the waist and pinch the lateral sides of the nose with the thumb and index finger for up to 15 minutes while breathing through the mouth.[17] Continued bleeding despite this intervention requires urgent medical intervention such as nasal packing.

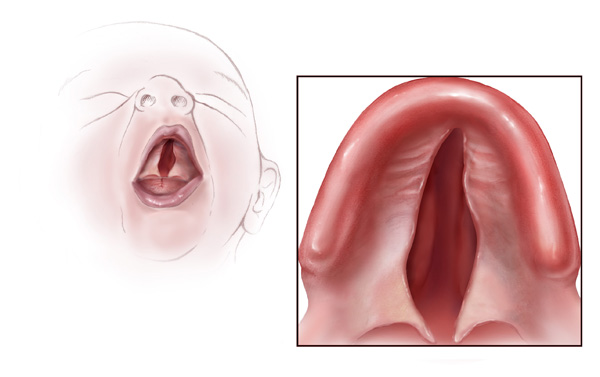

Cleft Lip and Palate

During embryonic development, the right and left maxilla bones come together at the midline to form the upper jaw. At the same time, the muscle and skin overlying these bones join together to form the upper lip. Inside the mouth, the palatine processes of the maxilla bones, along with the horizontal plates of the right and left palatine bones, join together to form the hard palate. If an error occurs in these developmental processes, a birth defect of cleft lip or cleft palate may result.

Cleft lip is a common developmental defect that affects approximately 1:1,000 births, most of which are male. This defect involves a partial or complete failure of the right and left portions of the upper lip to fuse together, leaving a cleft (gap). See Figure 7.18[18] for an image of an infant with a cleft lip.

A more severe developmental defect is a cleft palate that affects the hard palate, the bony structure that separates the nasal cavity from the oral cavity. See Figure 7.19[19] for an illustration of a cleft palate. Cleft palate affects approximately 1:2,500 births and is more common in females. It results from a failure of the two halves of the hard palate to completely come together and fuse at the midline, thus leaving a gap between the nasal and oral cavities. In severe cases, the bony gap continues into the anterior upper jaw where the alveolar processes of the maxilla bones also do not properly join together above the front teeth. If this occurs, a cleft lip will also be seen. Because of the communication between the oral and nasal cavities, a cleft palate makes it very difficult for an infant to generate the suckling needed for nursing, thus creating risk for malnutrition. Surgical repair is required to correct a cleft palate.[20]

Poor Oral Health

Despite major improvements in oral health for the population as a whole, oral health disparities continue to exist for many racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups in the United States. Healthy People 2020, a nationwide initiative geared to improve the health of Americans, identified improved oral health as a health care goal. A growing body of evidence has also shown that periodontal disease is associated with negative systemic health consequences. Periodontal diseases are infections and inflammation of the gums and bone that surround and support the teeth. Red, swollen, and bleeding gums are signs of periodontal disease. Other symptoms of periodontal disease include bad breath, loose teeth, and painful chewing.[21] In 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 42% of U.S. adults have some form of periodontitis, and almost 60% of adults aged 65 and older have periodontitis. See Figure 7.20[22] for an image of a patient with periodontal disease. Nurses may encounter patients who complain of bleeding gums, or they may discover other signs of periodontal disease during a physical assessment.

Because many Americans lack access to oral care, it is important for nurses to perform routine oral assessment and identify needs for follow-up. If signs and/or symptoms indicate potential periodontal disease, the patient should be referred to a dental health professional for a more thorough evaluation.[23]

Thrush/Candidiasis

Candidiasis is a fungal infection caused by Candida. Candida normally lives on the skin and inside the body without causing any problems, but it can multiply and cause an infection if the environment inside the mouth, throat, or esophagus changes in a way that encourages fungal growth.[24] See Figure 7.21[25] for an image of candidiasis.

Candidiasis in the mouth and throat can have many symptoms, including the following:

- White patches on the inner cheeks, tongue, roof of the mouth, and throat

- Redness or soreness

- Cotton-like feeling in the mouth

- Loss of taste

- Pain while eating or swallowing

- Cracking and redness at the corners of the mouth[26]

Candidiasis in the mouth or throat is common in babies but is uncommon in healthy adults. Risk factors for getting candidiasis as an adult include the following:

- Wearing dentures

- Diabetes

- Cancer

- HIV/AIDS

- Taking antibiotics or corticosteroids including inhaled corticosteroids for conditions like asthma

- Taking medications that cause dry mouth or have medical conditions that cause dry mouth

- Smoking

The treatment for mild to moderate cases of candidiasis infections in the mouth or throat is typically an antifungal medicine applied to the inside of the mouth for 7 to 14 days, such as clotrimazole, miconazole, or nystatin.

"Meth Mouth"

The use of methamphetamine (i.e., meth), a strong stimulant drug, has become an alarming public health issue in the United States. A common sign of meth abuse is extreme tooth and gum decay often referred to as “Meth Mouth.” See Figure 7.22[27] for an image of Meth Mouth.

Signs of Meth Mouth include the following:

- Dry Mouth. Methamphetamines dry out the salivary glands, and the acid content in the mouth will start to destroy the enamel on the teeth. Eventually this will lead to cavities.

- Cracked Teeth. Methamphetamine can make the user feel anxious, hyper, or nervous, so they clench or grind their teeth. You may see severe wear patterns on their teeth.

- Tooth Decay. Meth users crave beverages high in sugar while they are “high.” The bacteria that feed on the sugars in the mouth will secrete acid, which can lead to more tooth destruction. With meth users, tooth decay will start at the gum line and eventually spread throughout the tooth. The front teeth are usually destroyed first.

- Gum Disease. Methamphetamine users do not seek out regular dental treatment. Lack of oral health care can contribute to periodontal disease. Methamphetamines also cause the blood vessels that supply the oral tissues to shrink in size, reducing blood flow, causing the tissues to break down.

- Lesions. Users who smoke meth present with lesions and/or burns on their lips or gingival inside the cheeks or on the hard palate. Users who snort may present burns in the back of their throats.[28]

Nurses who notice possible signs of Meth Mouth should report their concerns to the health care provider, not only for a referral for dental care, but also for treatment of suspected substance abuse.

Dysphagia

Dysphagia is the medical term for difficulty swallowing that can be caused by many medical conditions. Nurses are often the first health care professionals to notice a patient’s difficulty swallowing as they administer medications or monitor food intake. Early identification of dysphagia, especially after a patient has experienced a cerebrovascular accident (i.e., stroke) or other head injury, helps to prevent aspiration pneumonia.[29] Aspiration pneumonia is a type of lung infection caused by material from the stomach or mouth entering the lungs and can be life-threatening.

Signs of dysphagia include the following:

- Coughing during or right after eating or drinking

- Wet or gurgly sounding voice during or after eating or drinking

- Extra effort or time required to chew or swallow

- Food or liquid leaking from mouth

- Food getting stuck in the mouth

- Difficulty breathing after meals[30]

The Barnes-Jewish Hospital-Stroke Dysphagia Screen (BJH-SDS) is an example of a simple, evidence-based bedside screening tool that can be used by nursing staff to efficiently identify swallowing impairments in patients who have experienced a stroke. See internet resource below for an image of the dysphagia screening tool. The result of the screening test is recorded as a “fail” if any of the five items tested are abnormal (Glasgow Coma Scale < 13, facial/tongue/palatal asymmetry or weakness, or signs of aspiration on the 3-ounce water test) or “pass” if all five items tested were normal. Patients with a failed screening result are placed on nothing-by-mouth (NPO) status until further evaluation is completed by a speech therapist. For more information about using the Glasgow Coma Scale, see the "Assessing Mental Status" subsection in the “Neurological Assessment” chapter.

Enlarged Lymph Nodes

Lymphadenopathy is the medical term for swollen lymph nodes. In a child, a node is considered enlarged if it is more than 1 centimeter (0.4 inch) wide. See Figure 7.23[31] for an image of an enlarged cervical lymph node.

Common infections such as a cold, pharyngitis, sinusitis, mononucleosis, strep throat, ear infection, or infected tooth often cause swollen lymph nodes. However, swollen lymph nodes can also signify more serious conditions. Notify the health care provider if the patient’s lymph nodes have the following characteristics:

- Do not decrease in size after several weeks or continue to get larger

- Are red and tender

- Feel hard, irregular, or fixed in place

- Are associated with night sweats or unexplained weight loss

- Are larger than 1 centimeter in diameter

The health care provider may order blood tests, a chest X-ray, or a biopsy of the lymph node if these signs occur. [32]

Thyroid

The thyroid is a butterfly-shaped gland located at the front of the neck that controls many of the body’s important functions. The thyroid gland makes hormones that affect breathing, heart rate, digestion, and body temperature. If the thyroid makes too much or not enough thyroid hormone, many body systems are affected. In hypothyroidism, the thyroid gland doesn’t produce enough hormone and many body functions slow down. When the thyroid makes too much hormone, a condition called hyperthyroidism, many body systems speed up.[33]

A goiter is an abnormal enlargement of the thyroid gland that can occur with hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism. If you find a goiter when assessing a patient’s neck, notify the health care provider for additional testing and treatment. See Figure 7.24[34] for an image of a goiter.

Wounds should be assessed and documented at every dressing change. Wound assessment should include the following components:

- Anatomic location

- Type of wound (if known)

- Degree of tissue damage

- Wound bed

- Wound size

- Wound edges and periwound skin

- Signs of infection

- Pain[35]

These components are further discussed in the following sections.

Anatomic Location and Type of Wound

The location of the wound should be documented clearly using correct anatomical terms and numbering. This will ensure that if more than one wound is present, the correct one is being assessed and treated. Many agencies use images to facilitate communication regarding the location of wounds among the health care team. See Figure 20.16[36] for an example of facility documentation that includes images to indicate wound location.

The location of a wound also provides information about the cause and type of a wound. For example, a wound over the sacral area of an immobile patient is likely a pressure injury, and a wound near the ankle of a patient with venous insufficiency is likely a venous ulcer. For successful healing, different types of wounds require different treatments based on the cause of the wound.

Degree of Tissue Damage

It is important to continually assess the degree of tissue damage in pressure injuries because the level of damage can worsen if they are not treated appropriately. Refer to the “Staging” subsection of “Pressure Injuries” in the “Basic Concepts Related to Wounds” section for more information about tissue damage.

Wound Base

Assess the color of the wound base. Recall that healthy granulation tissue appears pink due to the new capillary formation. It is moist, painless to the touch, and may appear “bumpy.” Conversely, unhealthy granulation tissue is dark red and painful. It bleeds easily with minimal contact and may be covered with biofilm. The appearance of slough (yellow) or eschar (black) in the wound base should be documented and communicated to the health care provider because it likely will need to be removed for healing. Tunneling and undermining should also be assessed, documented, and communicated.

Type and Amount of Exudate

The color, consistency, and amount of exudate (drainage) should be assessed and documented at every dressing change. The amount of drainage from wounds is categorized as scant, small/minimal, moderate, or large/copious. Use the following descriptions to select the appropriate terms:[37]

- No exudate: The wound base is dry.

- Scant amount of exudate: The wound is moist but no measurable amount of exudate appears on the dressing.

- Minimal amount of exudate: Exudate covers less than 25% of the size of the bandage.

- Moderate amount of drainage: Wound tissue is wet, and drainage covers 25% to 75% of the size of the bandage.

- Large or copious amount of drainage: Wound tissue is filled with fluid, and exudate covers more than 75% of the bandage.[38]

The type of wound drainage should be described using medical terms such as serosanguinous, sanguineous, serous, or purulent.

- Sanguineous: Sanguineous exudate is fresh bleeding.[39]

- Serous: Serous drainage is clear, thin, watery plasma. It’s normal during the inflammatory stage of wound healing, and small amounts are considered normal wound drainage.[40]

- Serosanguinous: Serosanguineous exudate contains serous drainage with small amounts of blood present.[41]

- Purulent: Purulent exudate is thick and opaque. It can be tan, yellow, green, or brown. It is never considered normal in a wound bed, and new purulent drainage should always be reported to the health care provider.[42] See Figure 20.17[43] for an image of purulent drainage.

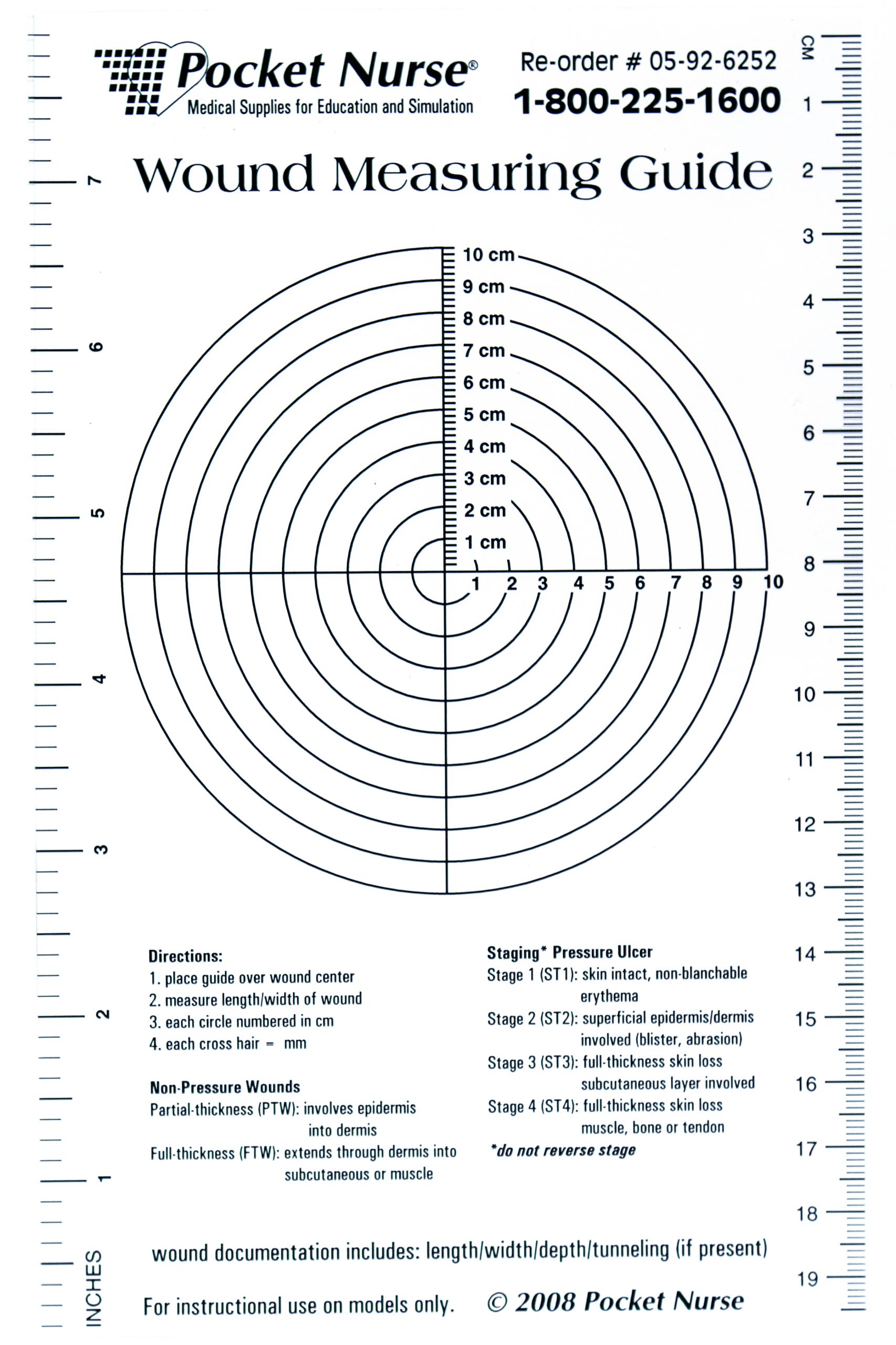

Wound Size

Wounds should be measured on admission and during every dressing change to evaluate for signs of healing. Accurate wound measurements are vital for monitoring wound healing. Measurements should be taken in the same manner by all clinicians to maintain consistent and accurate documentation of wound progress. This can be difficult to accomplish with oddly shaped wounds because there can be confusion about how consistently to measure them. Wounds should be described by length by width, with the length of the wound based on the head-to-toe axis. The width of a wound should be measured from side to side laterally. If a wound is deep, the deepest point of the wound should be measured to the wound surface using a sterile, cotton-tipped applicator. Many facilities use disposable, clear plastic measurement tools to measure the area of a wound healing by secondary intention. Measurements are typically documented in centimeters. See Figure 20.18[44] for an image of a wound measurement tool.

Tunneling can occur in a full-thickness wound that can lead to abscess formation. The depth of a tunneling can be measured by gently probing the tunnelled area with a sterile, cotton-tipped applicator from the wound base to the end of the tract. When probing a tunnel, it is imperative to not force the swab but only insert until resistance is felt to prevent further damage to the area. The location of the tunnel in the wound should be documented using the analogy of a clock face, with 12:00 pointing toward the patient’s head.[45]

Undermining occurs when the tissue under the wound edges becomes eroded, resulting in a pocket beneath the skin at the wound's edge. Undermining is measured by inserting a probe under the wound edge directed almost parallel to the wound surface until resistance is felt. The amount of undermining is the distance from the probe tip to the point at which the probe is level with the wound edge. Clock terms are also used to identify the area of undermining.[46]

Wound Edges and Periwound Skin

If the wound is healing by primary intention, it should be documented if the wound edges are well-approximated (closed together) or if there are any signs of dehiscence. The skin outside the outer edges of the wound, called the periwound skin, provides information related to wound development or healing. For example, a venous ulcer often has excess wound drainage that macerates the periwound skin, giving it a wet, waterlogged appearance that is soft and gray white in color.[47] See Figure 20.19[48] for an image of erythematous periwound with partial dehiscence.

Signs of Infection

Wounds should be continually monitored for signs of infection. Signs of localized wound infection include erythema (redness), induration (area of hardened tissue), pain, edema, purulent exudate (yellow or green drainage), and wound odor.[49] New signs of infection should be reported to the health care provider with an anticipated order for a wound culture.

Pain

The intensity of pain that a patient is experiencing with a wound should be assessed and documented. If a patient experiences pain during dressing changes, it should be managed with administration of pain medication before scheduled dressing changes. Be aware that the degree of pain may not correlate to the extent of tissue damage. For example, skin tears are often painful because the nerve endings are exposed in the dermal layer, whereas patients with severe diabetic ulcers on their feet may experience little or no pain because of existing neuropathic damage.[50]