99 Introduction

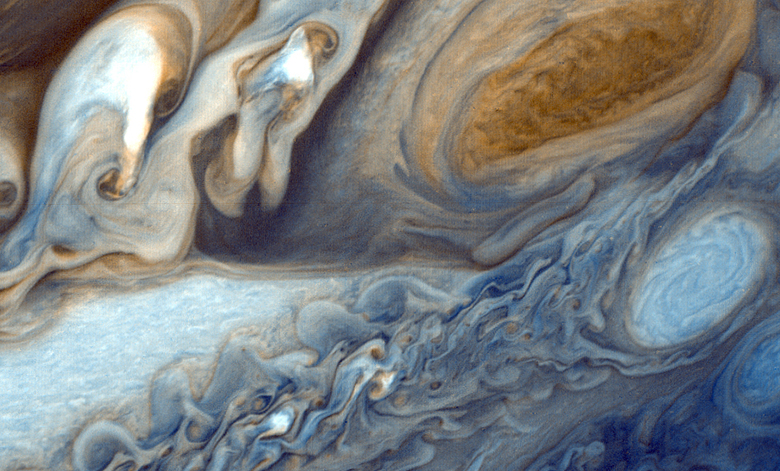

Figure 13.1 View from Voyager I Launched by NASA on September 5, 1977, Voyager I’s primary mission was to provide detailed images of Jupiter, Saturn, and their moons. It took this photograph of Jupiter on its journey. In August of 2012, Voyager I entered interstellar space—the first human-made object to do so—and it is expected to send data and images back to earth until 2025. Such a technological feat entails many economic principles. (Credit: modification of “Voyager’s View of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot” by NASA/JPL, Public Domain)

Chapter Objectives

In this chapter, you will learn about:

- Why the Private Sector Underinvests in Technologies

- How Governments Can Encourage Innovation

- Public Goods

Introduction to Positive Externalities and Public Goods

Bring It Home

The Benefits of Voyager I Endure

The rapid growth of technology has increased our ability to access and process data, to navigate through a busy city, and to communicate with friends on the other side of the globe. The research and development efforts of citizens, scientists, firms, universities, and governments have truly revolutionized the modern economy. To get a sense of how far we have come in a short period of time, let’s compare one of humankind’s greatest achievements to the smartphone.

In 1977 the United States launched Voyager I, a spacecraft originally intended to reach Jupiter and Saturn, to send back photographs and other cosmic measurements. Voyager I, however, kept going, and going—past Jupiter and Saturn—right out of our solar system. At the time of its launch, Voyager had some of the most sophisticated computing processing power NASA could engineer (8,000 instructions per second), but today, we Earthlings use handheld devices that can process 14 billion instructions per second.

Still, the technology of today is a spillover product of the incredible feats NASA accomplished over forty years ago. NASA research, for instance, is responsible for the kidney dialysis and mammogram machines that we use today. Research in new technologies not only produces private benefits to the investing firm, or in this case to NASA, but it also creates benefits for the broader society. In this way, new knowledge often becomes what economists refer to as a public good. This leads us to the topic of this chapter—technology, positive externalities, public goods, and the role of government in encouraging innovation and the social benefits that it provides.

As economist Mariana Mazzucato explores in her well-known work The Entrepreneurial State, what makes a smartphone smart? What allows its apps to help you navigate new towns while getting updates about your home, all while your hands are on the steering wheel and your children are in the back seat watching their shows? For starters, the internet, cell tower networks, GPS, and voice activation. Each of these, and many other technologies we rely on, were developed with intensive government support. For example, GPS, which enables many cell phone functions beyond the frequently used mapping and ride-sharing applications, was developed by the U.S. Department of Defense over several generations of satellite tracking and complex computer algorithm development. The U.S. government still provides GPS for many of the world’s users.

We do not often think of the government when we consider our leading products and entrepreneurs. We think of Apple, Google, Lyft, Tesla, Fitbit, and so on—creative innovators who built on the tools provided by these government efforts, using them in transformative ways. We may not think of the estimated $19 billion per year that the U.S. spends to maintain the GPS system, but we would certainly think of it if it suddenly went away. (Beyond the impact on our daily lives, economists estimate U.S. businesses alone would lose about $1 billion per day without GPS.)

Mazzucato is one of several prominent economists advocating for an embrace of continued government-sponsored innovations in order to build economic prosperity, reduce inequality, and manage ongoing challenges such as drought, coastal changes, and extreme weather. She argues that competitive, private sector markets are often resistant to the risks involved with large-scale innovation, because failed experiments and lack of uptake lead to massive corporate and personal losses. Governments can take on riskier research and development projects. Because government spending is fueled by taxpayers, and all innovation leads to some level of employment change, these proposals are certainly complex and challenging to implement.

This chapter deals with some of these issues: Will private companies be willing to invest in new technology? In what ways does new technology have positive externalities? What motivates inventors? What role should government play in encouraging research and technology? Are there certain types of goods that markets fail to provide efficiently, and that only government can produce? What happens when consumption or production of a product creates positive externalities? Why is it unsurprising when we overuse a common resource, like marine fisheries?

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e