1 Foundations of Economics

Laura Prince and OpenStax

Learning Objectives

- Economic Way of Thinking and Framework

- Cost and Benefits

- Scarcity: The Basic Economic Problem

- Economic Systems

- Opportunity Cost

- Productivity

- The Price System

- The Circular Flow of Market Economy

- Role of Government – Externalities

Economists use a framework to approach complex problems and make decisions.

The economic way of thinking uses a framework to examine how people make choices under conditions of scarcity and systems of production, consumption, and distribution. The practice of economics often involves analyzing complex problems. Although economists may differ in their views, they have developed an economic way of thinking based on several principles or a framework.

The economic way of thinking framework consists of:

- Every Choice has a Cost

- People Make Better Choices by Thinking at the Margin

- Rational Self-Interest

- Economic Models

- Positive versus Normative Economics

Every Choice Has a Cost

Because human and property resources are scarce, individuals and societies must choose how to best use them. Making choices requires trading one thing for another. At the core of economics is the idea that there is no such thing as a “free lunch.” For example, if a friend pays for your lunch, making it “free” to you, it is not actually free—it comes at a cost to your friend and ultimately to society. This fundamental principle of economics states that every choice involves a cost.

For example, school lunches in Wisconsin are free to students, but they are not free to society. Taxes from taxpayers cover the cost of these lunches. What are we giving up to use tax money for free school lunches? Are we sacrificing funds that could fight climate change or help those facing eviction due to job loss? More specifically, the cost is termed the opportunity cost. What opportunity are we giving up for free lunches? This always involves a trade-off. On the flip side, what are the benefits of the “free lunch” for students? Do we benefit as individuals and as a society when students are fed? Does it make learning more productive, thereby benefiting the state of Wisconsin?

The cost of any choice is the value of the best opportunity that is foregone by making the choice. This is the opportunity cost. For example, you can choose to remain in college or quit college. If you quit, you may find a job at Burger King and earn money to buy clothes, rent videos, go skiing, and hang out with friends. If you remain in college, you will not afford these things now. However, your education will enable you to find a better job later, allowing you to afford these things and more. In addition, the abilities you learn in college will benefit society.

People Make Better Choices by Thinking at the Margin

Economists maintain that people make better choices by thinking at the margin. Making a choice at the margin means deciding to do a little more or a little less of an activity. As a student, you can allocate the next hour to sleeping or studying. In making this decision, you compare the benefit of extra study time to the cost of foregone sleep.

Most choices involve marginal analysis, which means examining the benefits and costs of choosing a little more or a little less of a good. People naturally compare costs and benefits, but often we look at total costs and total benefits. The optimal choice necessitates comparing how costs and benefits change from one option to another. You might think of marginal analysis as “change analysis.” Marginal analysis is used throughout economics.

The law of diminishing marginal utility means that as a person receives more of a good, the additional (or marginal) utility (satisfaction from the good or service) from each additional unit of the good declines. In other words, the first slice of pizza brings more satisfaction than the sixth.

The law of diminishing marginal utility explains why people and societies rarely make all-or-nothing choices. You would not say, “My favorite food is ice cream, so I will eat nothing but ice cream from now on.” Instead, even if you get a very high level of utility from your favorite food, if you ate it exclusively, the additional or marginal utility from those last few servings would not be very high. Similarly, most workers do not say: “I enjoy leisure, so I’ll never work.” Instead, workers recognize that even though some leisure is nice, a combination of all leisure and no income is not attractive. The budget constraint framework suggests that when people make choices in a world of scarcity, they will use marginal analysis and think about whether they would prefer a little more or a little less.

Rational Self-Interest

Economics is founded on the assumption of rational self-interested humans. This means that people act as if they are motivated by self-interest and respond predictably to opportunities for gain. In other words, people try to make the best of any situation. Often, making the best of a situation involves maximizing the value of some quantity. As a student, getting high grades may be an incentive to study hard (cost) because they may help you obtain a job interview with an employer (benefit) or get accepted to a college (benefit). This, in turn, will earn you more “pleasure,” “benefit,” or “money” (benefit).

We assume that economic incentives underlie the rational decisions that people make. Because income is limited and goods have prices, we cannot buy all the things we would like to have. Therefore, we should choose an attainable combination of goods and/or services that will maximize our satisfaction. Of course, self-interest does not always imply increasing one’s wealth, as measured in dollars, or one’s satisfaction from the amount of goods and/or services consumed. In addition to economic motivations, people also have goals pertaining to friendship, love, altruism, creativity, and the like.

Economic Models

Like other sciences, economics uses models. In chemistry, you may have seen a model of an atom, a device with blue, green, and red balls that represent neutrons, electrons, and protons. Economic models are not built with plastic or cardboard but rather with words, diagrams, and mathematical equations.

Economic models, or theories, are simplified representations of the real world that we use to help us understand, explain, and predict economic phenomena. Economic models might explain inflation, unemployment, wage rates, and more. For example, an economic model might tell us how the quantity of movies that consumers purchase will change if the seller raises the price. We will use economic models to help us understand contemporary economic issues.

Positive vs. Normative Economics

It is important to realize that economics is not always free of value judgments. When thinking about economic questions, we must distinguish questions of fact from questions of values or fairness.

Positive economics describes the facts of the economy. Positive economics deals with the way in which the economy works. Positive economics considers such questions as, why do computer scientists earn more than janitors? What is the economic effect of reducing taxes? Does free trade result in job loss for low-skilled workers? Although these questions are difficult to answer, they can be addressed by economic analysis and empirical evidence.

Normative economics involves value judgments that cannot be tested empirically. Ethical standards and norms of fairness underlie normative economics. For example, should the United States penalize China for violating US patent and copyright laws? Should welfare payments be reduced to encourage the unemployed to find income-producing jobs? Should all Americans have equal access to healthcare? Because these questions involve value judgments instead of facts, there are no right or wrong answers.

Both positive and normative economics are important and will be considered in this course.

Cost/Benefit: The Study of Trade-Offs and Choices

Cost-benefit analysis in economics is the exercise of evaluating a planned action by determining and quantifying the factors involved.

- Add all the positive factors. These are the benefits.

- Identify, quantify, and subtract all the negatives, the costs, including opportunity cost.

- The difference between the two indicates whether the planned action is advisable.

The real key to doing a successful cost-benefit analysis is making sure to include all the costs and all the benefits and properly quantify them. It is the fundamental assessment behind virtually every economic and business decision because business managers do not want to spend money unless the benefits that derive from the expenditure are expected to exceed the costs.

The big difference between business cost/benefit analysis and economic cost/benefit analysis is that economics includes all opportunity costs, while businesses do not. For example, what does it cost society if a business pollutes the environment or cuts down all trees to make a profit? A business does not typically look at those costs. They are simply concerned with the business costs and benefits and how to make a profit, not what is good or bad for society.

Cost-benefit analysis is a decision support method used to help answer questions that often start with “what if” or “should we” (Inc.com, 2012).

Framework Example: Every Choice Has a Cost and Benefits

For example, you might want to consider the costs and benefits of going to college full time or working full time. You might list all of the benefits and all of the costs of each choice in order to find the choice that has the most benefits with the least amount of costs.

The concept of opportunity cost reflects the scarcity of our resources (the bottom line in economics)—especially time and money.

When we integrate opportunity cost into our decision-making, we ensure the most efficient use of our scarce resources.

Suppose, for example, we wish to evaluate the benefits and costs of a proposal to control air pollution emissions from a large factory. On the benefit side, pollution reduction will mean reduced damage to exposed materials, diminished health risks to people living nearby, improved visibility, and even new jobs for those who manufacture pollution control equipment. On the cost side, the required investments in pollution control may cause the firm to raise the price of its products, close down several higher-cost operations at its plant, lay off workers, and postpone other planned investments designed to modernize its production facilities.

Introduction: One way to understand the tradeoffs that need to be made is to think it in terms of costs and benefits.

After watching the video, consider this case: According to a University of Utah study, using a cell phone while driving, whether handheld or hands-free, delays a driver’s reactions as much as having a blood alcohol concentration at the legal limit of 0.08 percent. Thus, driving while texting can create a serious danger.

Do some research and consider these questions:

- List the groups or individuals most affected by the situation.

- What do YOU think the government should do or not do?

- What are the COSTS and BENEFITS of your solution?

- Which individuals or groups will be the WINNERS (better off than before) if your government solution is adopted? Which individuals or groups will be LOSERS (worse off than before)?

NOTE: Even though there is a terrible cost to driving while texting, there are WINNERS that do benefit, such as the companies that clean up accidents on the highway, cell phone companies, etc.

Scarcity: The Most Basic Problem

Scarcity

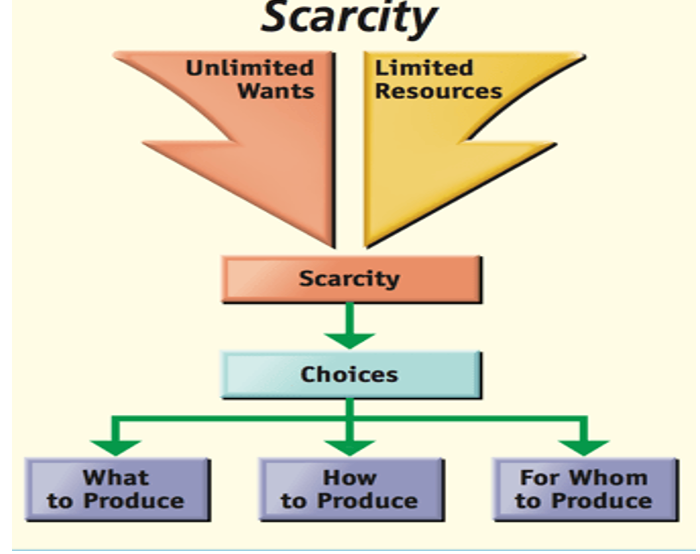

Scarcity is the tension between unlimited human wants and needs and the limited productive resources available for satisfying these desires. This concept highlights that economic productive resources—land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurial ability—are limited, not infinite.

Note: Be careful to think this through—the economic use of the word does not correspond exactly with the common usage of the word.

The study of economics explains how productive resources are used to provide the goods and services that satisfy human wants and needs. Productive resources are limited, and the goods and services that can be produced from them are also limited. However, remember that the goods and services wanted by individuals and societies are virtually unlimited. We, as humans, tend to want it all.

Productive Resources

Every society is endowed with resources used to produce the goods and services that enable society to survive and prosper. The productive resources are:

- Land: This includes all natural resources, such as minerals, timber, soil, water, and the land itself (created by nature).

- Labor: This describes the human work effort, both physical and mental, expended in production.

- Capital: This includes human-made physical resources such as buildings, tools, machines, and equipment used in production (created by humans).

- Entrepreneurial ability: This combines the other three factors of production to add to supply. Entrepreneurs are risk-takers seeking profit.

Remember: Productive resources are limited, but human wants are unlimited.

Scarcity is one of the foundational ideas in economics, and its implications can drastically impact how a society produces its goods and services. In economics, the term “scarcity” refers to the idea that an economic system cannot possibly produce all the goods and services that consumers want.

The combined effect of unlimited wants and limited resources creates a reduction in the availability of goods and services. Ultimately, this suggests that consumers must make selective and complicated decisions about how finite resources (land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurial ability) should be used. As we will see in the case of natural water supplies below, incorrect decisions in these areas can lead to drastically negative consequences in the everyday lives of consumers.

Economic Examples

(Source: https://discusseconomics.com/global-economics/foundations-economics-law-scarcity/)

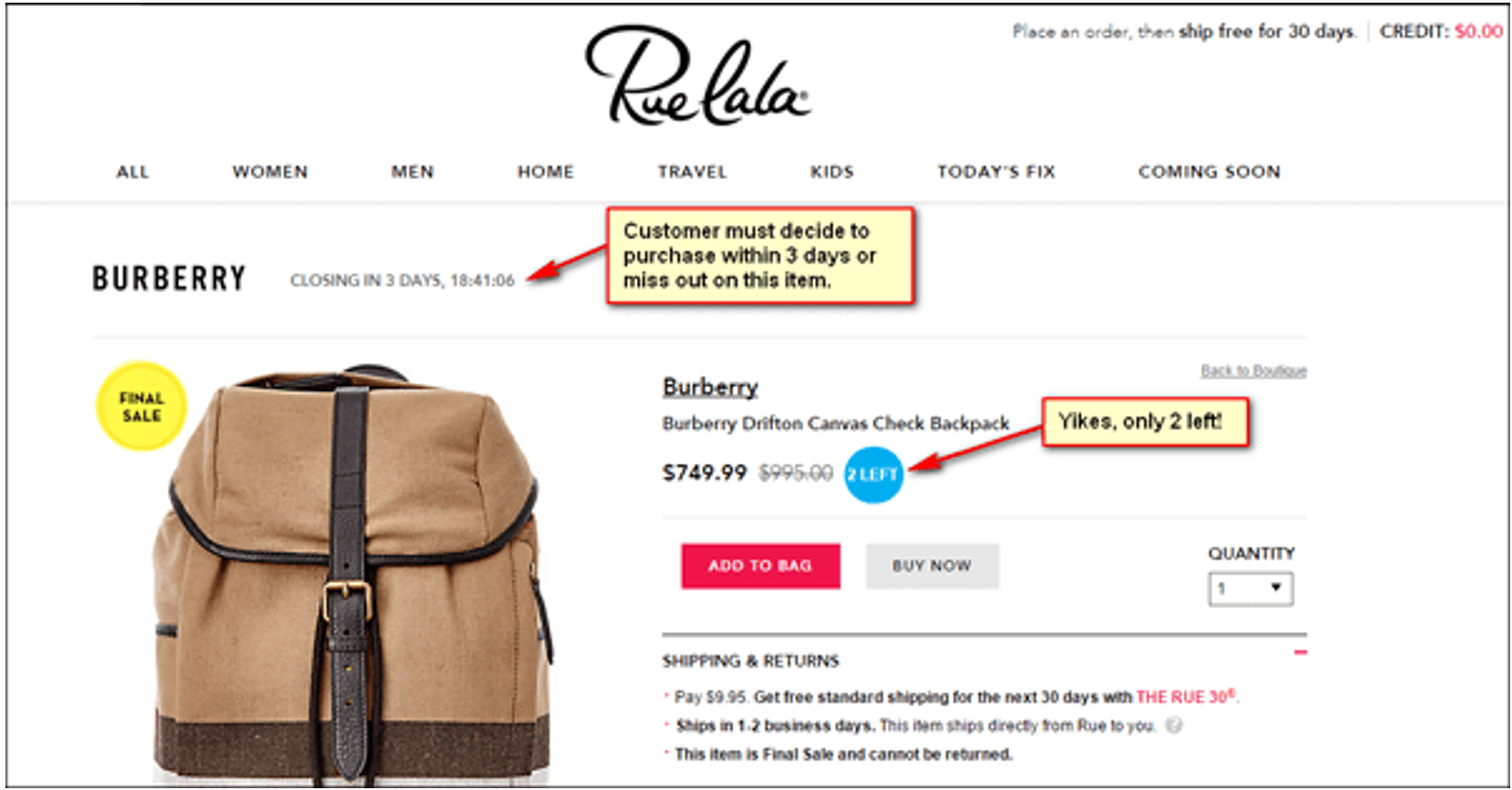

For some, these ideas might sound like unrelatable, abstract economic concepts. But the reality is that there are occurrences that can easily be found on a day-to-day basis. In the graphic below, we can see a scenario that many online shoppers might find when making regular purchasing decisions.

Anyone interested in this Burberry handbag faces a purchasing decision that is closely tied to the Law of Scarcity. Discounted prices can be found here but time and resource availability are limited to three days. In addition to this, there are only two of these handbags available in the market.

This means a consumer must act quickly in order to take advantage of the item’s sale price. Of course, these are all factors that can have a significant impact on the ebb and flow of the daily activity that is seen in the consumer markets. But the effects of these trends can extend into the macro-economy, as well.

Example: Global Economic Theory in Practice

To illustrate this idea using real-world trends, we can look at water as a resource commodity that serves many of the most basic human needs. But what many may not know is that a growing number of people face water scarcity to an alarming degree.

Scarcity Summary

As we can see, scarcity can play an important role in the daily lives of consumers. Ideas that may seem abstract or overly academic can actually have a significant influence on how a society produces and sells its goods and services in the market. As long as the world has limited means and unlimited wants, there will always be choices that must be made. The laws of economics can help us make more informed decisions in these areas so that we can meet as many human needs as possible.

How to Handle Scarcity within Economic Systems

To solve this basic problem, every society must answer these questions:

- What goods and services will be produced?

- How will the goods and services be produced?

- How will we decide who gets what?

The answers to these questions will be based on the type of economic system used in our society.

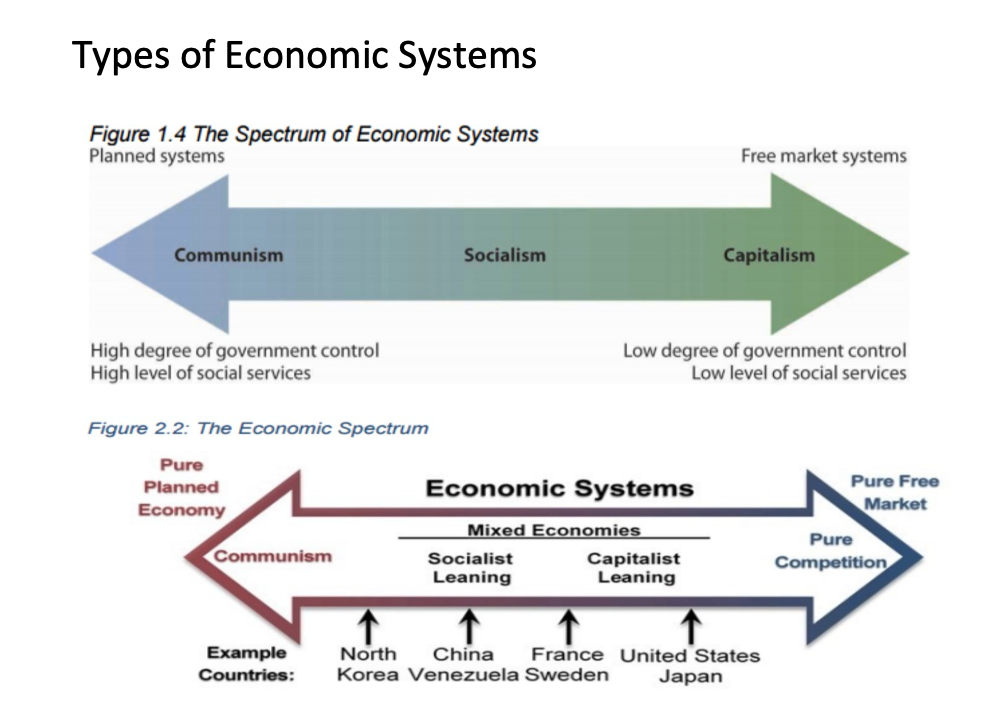

Types of Economic Systems

Take a look at the graphic below and notice the common names for the four types of systems:

- Traditional

- Command

- Market

- Mixed

Several fundamental types of economic systems exist to answer the three questions of what, how, and for whom to produce: traditional, command, market, and mixed. These systems help societies address the main questions all societies must face when dealing with scarcity. Let’s look at how each system deals with scarcity.

Traditional Economies

In a traditional economy, economic decisions are based on custom and historical precedent. For example, in tribal cultures or societies with a caste system, people often perform the same type of work as their parents and grandparents, regardless of ability or potential. The answers to what, how, and who are based on tradition:

- What to produce: What our parents produced.

- How to produce: The way it has always been done.

- Who gets what: Determined by tradition.

Command (Centralized) Economies

In a command economy, governmental planning groups make the basic economic decisions. They determine which goods and services to produce, their prices, and wage rates. Cuba and North Korea are examples of command economies, often referred to as Communism.

- What to produce: The government or a central authority decides for the whole society.

- How to produce: The government makes this decision. For example, if the government decides robots will be used, then robots will make everything.

- Who gets what: The government decides. In Russia, it may be decided by a few oligarchs, while in North Korea, Kim Jong-un decides. The rest of society gets very little.

Market (Decentralized) Economies

In a market economy, economic decisions are guided by price changes as individual buyers and sellers interact in the marketplace. This type of economy is often referred to as the price system, free market, or capitalism. The economies of the United States, Singapore, and Japan are identified as market economies since prices play a significant role in guiding economic activity.

- What to produce: Based on consumer demand.

- How to produce: Determined by producers seeking the most efficient methods.

- Who gets what: Those who can pay for it.

Mixed Economies

There are no pure command or pure market economies. To some degree, all modern economies have characteristics of both systems and are therefore referred to as mixed economies. For example, in the United States, the government makes many important economic decisions, even though the price system is predominant. Even in strict command economies, private individuals frequently engage in market activities, particularly in small towns and villages.

In the U.S. mixed economy (market and command), consumers make the majority of decisions, but the government also establishes rules and taxes to provide necessary services (e.g., garbage disposal, military protection).

Key Point to Remember about Scarcity:

Every individual and every society must deal with the problem of scarcity. Every society, regardless of its political structure, must develop an economic system to determine how to use its limited resources to answer the three basic questions of what, how and for whom to produce.

Dealing with Scarcity – Opportunity Cost

Because of Scarcity… There Are No Free Lunches!

Because of scarcity, every time a choice is made, there are alternatives that are not chosen. More precisely, there is always one next best alternative that is not chosen. In economics, the value of the next best alternative is called opportunity cost. Both producers (those who provide goods and services) and consumers (those who use goods and services) incur opportunity costs when making decisions.

For example, a business person who uses a building to operate an insurance business cannot use the same building to produce pizzas. A consumer who uses scarce income to purchase new carpet will have to forgo saving the money or buying something else. Because there are always alternate uses for limited resources, every economic decision has an opportunity cost.

A major goal of economics is to recognize and evaluate opportunity costs when making decisions. This is one of the major distinctions between the study of business and the study of economics. As consumers, we should realize that the cost of buying an item is not really its price; rather, it is the most valued item that cannot be bought. For producers, the opportunity cost is the next most valuable good or service that is not produced as a result of the decision to produce something else.

The concept of opportunity cost also relates to the use of time. Since time is scarce, the time spent doing one activity and not another is a cost.

CLEAR IT UP

What is the Opportunity Cost Associated with Increased Airport Security Measures?

After the terrorist plane hijackings on September 11, 2001, many steps were proposed to improve air travel safety. For example, the federal government could provide armed “sky marshals” who would travel inconspicuously with passengers. The cost of having a sky marshal on every flight would be roughly $3 billion per year. Retrofitting all U.S. planes with reinforced cockpit doors to make it harder for terrorists to take over the plane would cost about $450 million. Buying more sophisticated security equipment for airports, like three-dimensional baggage scanners and cameras linked to face recognition software, could cost another $2 billion.

However, the single biggest cost of greater airline security does not involve spending money. It is the opportunity cost of additional waiting time at the airport. According to the United States Department of Transportation (DOT), there were 895.5 million systemwide (domestic and international) scheduled service passengers in 2015. Since the 9/11 hijackings, security screening has become more intensive, causing longer procedures. On average, each air passenger spends an extra 30 minutes in the airport per trip. Economists commonly place a value on time to convert an opportunity cost in time into a monetary figure. Because many air travelers are relatively high-paid business people, conservative estimates set the average value of time for air travelers at $20 per hour. By these back-of-the-envelope calculations, the opportunity cost of delays in airports could be as much as 800 million × 0.5 hours × $20/hour, or $8 billion per year. Clearly, the opportunity costs of waiting time can be just as important as costs that involve direct spending.

In some cases, realizing the opportunity cost can alter behavior. Imagine, for example, that you spend $8 on lunch every day at work. You may know that bringing a lunch from home would cost only $3 a day. Therefore, the opportunity cost of buying lunch at the restaurant is $5 each day (the $8 for buying lunch minus the $3 your lunch from home would cost).

Five dollars each day may not seem like much. However, if you project that amount over a year—250 workdays × $5 per day equals $1,250, the cost of a decent vacation. If you think of the opportunity cost as “a nice vacation” instead of “$5 a day,” you might make different choices.

Key Point to Remember about Opportunity Cost and Scarcity:

Resources are limited and have alternative uses. Every economic choice has an opportunity cost.

Real Life Examples

Productivity: Key to Minimize the Effects of Scarcity

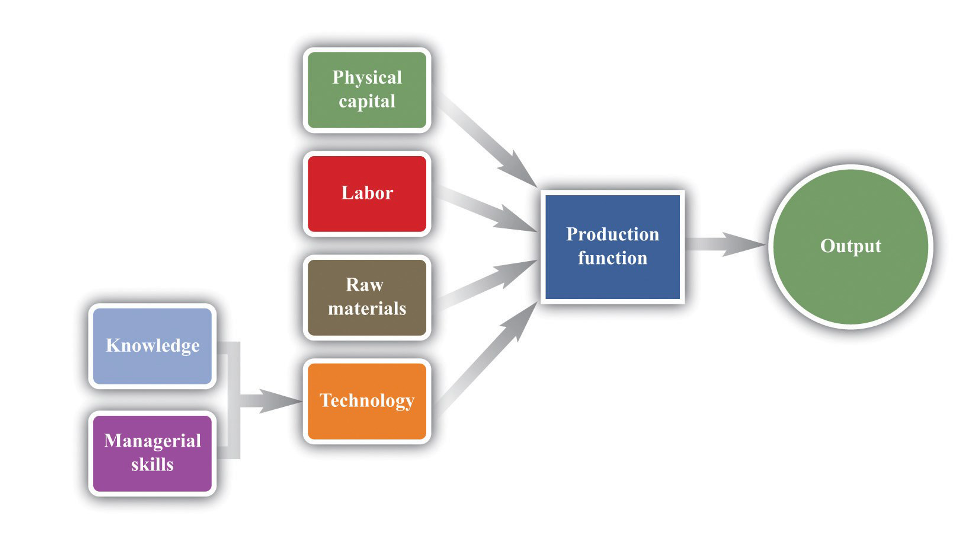

Production and Productivity

Economic activity is directed toward a distinct goal: minimizing the effects of scarcity. To achieve this, individuals and societies instinctively pursue economic activities that enable them to satisfy the most important of their wants using as few resources as possible. This has never been an easy task and has created much hardship. The progress made in minimizing the effects of scarcity has largely been due to more efficient use of productive resources in the production process. Remember, the productive resources are land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurial ability.

Economists refer to finished goods and services as output. Productive resources are the inputs. The important concept, productivity, measures the amount of output produced relative to the inputs used.

Productivity = Output/Input

Since labor (human resources) is a relatively easy input to measure and directly relates to wages and living standards, the term productivity usually refers to labor productivity. It is measured in terms of output per labor hour worked.

If workers produce 8 bookmarks in one hour, then 8/1, or 8, is the measure of their productivity. If they can produce 16 identical bookmarks in that same hour, this would be an increase in productivity.

In the long run, minimizing the effects of scarcity depends on increasing productivity. Societies with a high level of productivity typically also have a high standard of living. Health standards improve, and life expectancy increases with higher productivity. While the basic economic problem of scarcity cannot be eliminated, its effects can be reduced.

Three Ways to Increase Productivity or Economic Growth

- Adequate Amounts of Capital: Workers are more productive when they use tools, machines, and equipment. An adequate stock of capital for workers is necessary for high levels of productivity.Improvements in Technology: A farmer using a tractor can produce more than a farmer using a hoe. Technological improvements in capital stock have been the greatest factor in increasing productivity. For more on technological development. Research the Industrial Revolution for more information.

- Improvements in the Quality of Labor: Labor that is better trained and educated is more productive than unskilled labor. Increases in skills resulting from education, experience, and training are referred to as human capital.

- Increases in Specialization and Exchange: Because individuals have different skills and interests and because the time and resources necessary to learn new skills are scarce, there is a strong tendency toward specialization in the production of goods and services. This invariably leads to an increase in productivity. For example, a cobbler specializes in making shoes, while an accountant specializes in processing taxes.

The Price System: How the Market Directs Economic Activity

Because of scarcity, all societies must determine how to use their limited productive resources to answer the basic economic questions of what, how, and for whom to produce. To some degree, societies rely on the price system to accomplish this task.

Societies that rely primarily on prices are often called market economies or capitalism.

Prices as Guide

In a market economy, changing prices in the marketplace guide economic activity, simultaneously coordinating the diverse interests of millions of individuals in their roles as producers and consumers. For example, suppose that a new craze for tennis results in consumers purchasing more tennis rackets. If this is the only change in the market, the increase in demand for tennis rackets will cause their price to rise, resulting in more profits for producers of tennis rackets. The rise in profits will encourage existing producers to make and sell more rackets and will also attract new racket producers to enter the market. Eventually, the supply of tennis rackets will increase, and the price will fall again.

The important point to notice in this example is how prices coordinated the independent desires of consumers and producers. The rise in tennis racket prices communicated to producers that consumers desired more tennis rackets, provided a financial incentive (in the form of increased profits) to producers to meet this demand in the most efficient way possible, and determined who would get the rackets (those who were more willing and able to pay for them).

What is striking about the price system’s ability to answer these “what, how, and for whom” questions is the efficiency with which it is accomplished. This efficiency occurs because those who want to buy and sell products are free to do so in a way that benefits them the most, in competition with others. It is not necessary for the government to estimate society’s future demand for particular goods and services and then organize their production and distribution. In the price system, this complicated task happens more or less automatically, without government involvement.

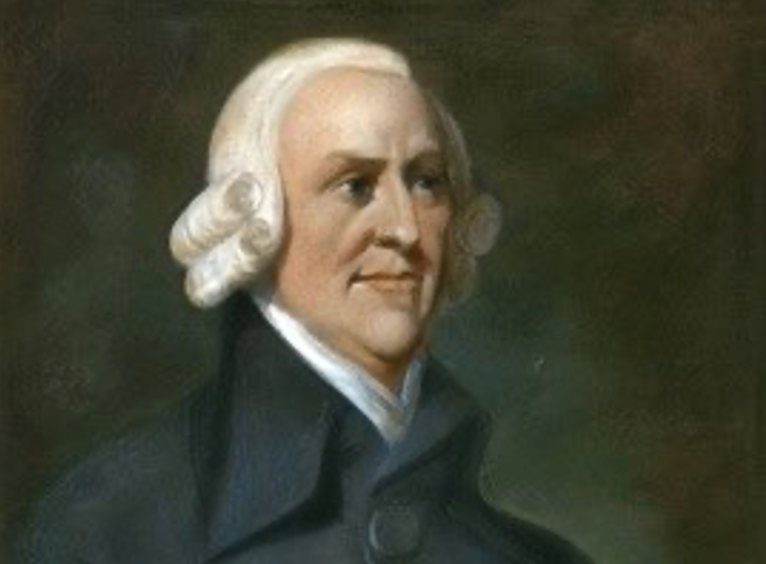

“Every individual endeavors to employ his capital so that its produce may be of greatest value. He generally neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. He intends only his own security, only his own gain. and he is in this led by an invisible hand to promote and in which was no part of his intention. By pursuing his own interest, he frequently promotes society more hen when he really intends to promote it.”

Government in Economics

Price Floors

When the government intervenes in a market economy to set or control prices, the results are predictable. If the price of a good or service is set above the true market price determined by supply and demand, there will be a surplus. This is because at higher prices, the quantity of a good supplied by producers will increase, while the quantity of goods demanded by consumers will decrease. The surplus of agricultural products in some countries is a good example.

For more, Price Controls

Price Ceilings

The opposite happens if the government sets the prices of goods or services below free market prices. In this case, the quantity of a good supplied by producers will decrease, while the quantity demanded by consumers will increase, resulting in a shortage characterized by long lines and shortages. Prices below market levels helped create the gasoline shortages of the 1970s in the United States. For more, Gas Prices 1970s

Market Equilibrium

Market price of a good or service is often referred to as the equilibrium price. This is a price that equalizes the amount producers want to sell and consumers want to buy. It is the price that clears the market for goods and services.

Different Roles of Government in Mixed Market Economy

Legal Framework

Without an effective legal framework, the price system cannot operate effectively. The government provides this framework by enforcing private contracts, defining private property rights, establishing uniform weights and measures, and creating and enforcing laws and rules governing marketplace activity.

Ensures Competition

The price market system operates effectively when there are many buyers and sellers competing in the marketplace. The government uses its powers to ensure that no single seller (monopoly) or a few sellers (oligopoly) control specific areas of the economy to the detriment of consumers. The government also establishes public service commissions to regulate natural monopolies, such as utility companies.

Provides Public Goods and Services

Certain goods and services, known as public goods, will be provided in less than the desired amount if left to the market system alone. The government, therefore, provides these goods and services. Examples include national defense, roads, flood control projects, and libraries.

Controls Externalities

Certain market transactions result in externalities, or spillovers, that cause positive or negative effects on others who are not directly part of the transactions. Pollution is an example of a negative spillover since polluters can pass on the effects or costs of pollution to others. The government attempts to correct this situation by prohibiting or regulating certain production activities. Education is commonly cited as a positive spillover. Since individuals and society benefit beyond the direct recipients and providers of education, the government uses taxes to provide public education.

Redistributes Income

The government uses tax revenues to provide a social “safety net” for individuals with little to no income. Examples include Medicaid, SNAP food benefits, public housing, the earned income tax credit, and free and reduced lunches.

Stabilizes the Economy

The US economy is characterized by business cycles that create hardships for many people. During downturns (recessions), there is little or no economic growth, often resulting in significant unemployment. During upturns, there may be more inflation. The government uses fiscal policy (taxing and spending decisions), and the Federal Reserve Banking System uses monetary policy (money supply decisions) to help keep the economy as stable as possible.

Note: Not everyone agrees that the government should assume all these roles. Some believe that government intervention may do more harm than good, especially when it redistributes income and attempts to stabilize the economy. In general, they contend that the growth of government results in a loss of individual liberty.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e