57 How the AD/AS Model Incorporates Growth, Unemployment, and Inflation

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Use the aggregate demand/aggregate supply model to show periods of economic growth and recession

- Explain how unemployment and inflation impact the aggregate demand/aggregate supply model

- Evaluate the importance of the aggregate demand/aggregate supply model

The AD/AS model can convey a number of interlocking relationships between the three macroeconomic goals of growth, unemployment, and low inflation. Moreover, the AD/AS framework is flexible enough to accommodate both the Keynes’ law approach that focuses on aggregate demand and the short run, while also including the Say’s law approach that focuses on aggregate supply and the long run. These advantages are considerable. Every model is a simplified version of the deeper reality and, in the context of the AD/AS model, the three macroeconomic goals arise in ways that are sometimes indirect or incomplete. In this module, we consider how the AD/AS model illustrates the three macroeconomic goals of economic growth, low unemployment, and low inflation.

Growth and Recession in the AD/AS Diagram

In the AD/AS diagram, long-run economic growth due to productivity increases over time will be represented by a gradual shift to the right of aggregate supply. The vertical line representing potential GDP (or the “full employment level of GDP”) will gradually shift to the right over time as well. Earlier Figure 24.7 (a) showed a pattern of economic growth over three years, with the AS curve shifting slightly out to the right each year. However, the factors that determine the speed of this long-term economic growth rate—like investment in physical and human capital, technology, and whether an economy can take advantage of catch-up growth—do not appear directly in the AD/AS diagram.

In the short run, GDP falls and rises in every economy, as the economy dips into recession or expands out of recession. The AD/AS diagram illustrates recessions when the equilibrium level of real GDP is substantially below potential GDP, as we see at the equilibrium point E0 in Figure 24.9. From another standpoint, in years of resurgent economic growth the equilibrium will typically be close to potential GDP, as equilibrium point E1 in that earlier figure shows.

Unemployment in the AD/AS Diagram

We described two types of unemployment in the Unemployment chapter. Short run variations in unemployment (cyclical unemployment) are caused by the business cycle as the economy expands and contracts. Over the long run, in the United States, the unemployment rate typically hovers around 5% (give or take one percentage point or so), when the economy is healthy. In many of the national economies across Europe, the unemployment rate in recent decades has only dropped to about 10% or a bit lower, even in good economic years. We call this baseline level of unemployment that occurs year-in and year-out the natural rate of unemployment and we determine it by how well the structures of market and government institutions in the economy lead to a matching of workers and employers in the labor market. Potential GDP can imply different unemployment rates in different economies, depending on the natural rate of unemployment for that economy.

The AD/AS diagram shows cyclical unemployment by how close the economy is to the potential or full GDP employment level. Returning to Figure 24.9, relatively low cyclical unemployment for an economy occurs when the level of output is close to potential GDP, as in the equilibrium point E1. Conversely, high cyclical unemployment arises when the output is substantially to the left of potential GDP on the AD/AS diagram, as at the equilibrium point E0. Although we do not show the factors that determine the natural rate of unemployment separately in the AD/AS model, they are implicitly part of what determines potential GDP or full employment GDP in a given economy.

Inflationary Pressures in the AD/AS Diagram

Inflation fluctuates in the short run. Higher inflation rates have typically occurred either during or just after economic booms: for example, the biggest spurts of inflation in the U.S. economy during the twentieth century followed the wartime booms of World War I and World War II. Conversely, rates of inflation generally decline during recessions. As an extreme example, inflation actually became negative—a situation called “deflation”—during the Great Depression. Even during the relatively short 1991-1992 recession, the inflation rate declined from 5.4% in 1990 to 3.0% in 1992. During the relatively short 2001 recession, the rate of inflation declined from 3.4% in 2000 to 1.6% in 2002. During the deep recession of 2007–2009, the inflation rate declined from 3.8% in 2008 to –0.4% in 2009. Some countries have experienced bouts of high inflation that lasted for years. In the U.S. economy since the mid–1980s, inflation does not seem to have had any long-term trend to be substantially higher. Instead, it has stayed in the 1–5% range annually.

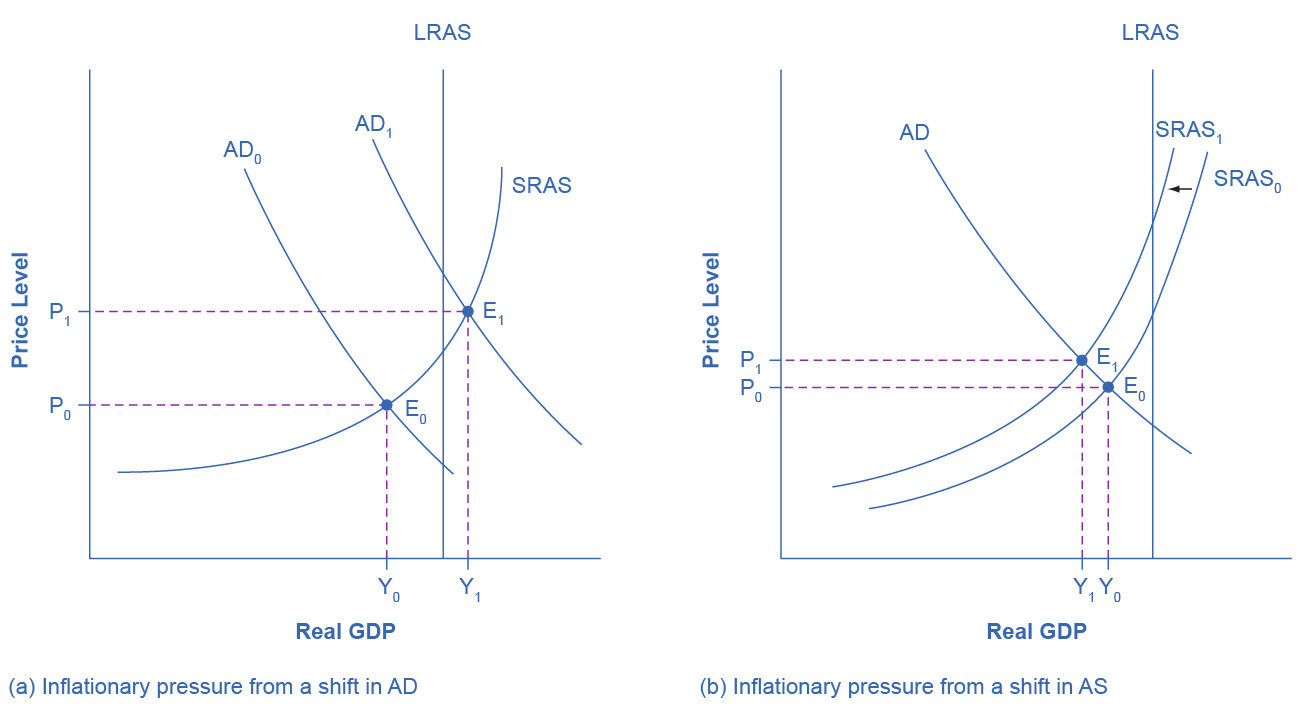

The AD/AS framework implies two ways that inflationary pressures may arise. One possible trigger is if aggregate demand continues to shift to the right when the economy is already at or near potential GDP and full employment, thus pushing the macroeconomic equilibrium into the AS curve’s steep portion. In Figure 24.10 (a), there is a shift of aggregate demand to the right. The new equilibrium E1 is clearly at a higher price level than the original equilibrium E0. In this situation, the aggregate demand in the economy has soared so high that firms in the economy are not capable of producing additional goods, because labor and physical capital are fully employed, and so additional increases in aggregate demand can only result in a rise in the price level.

Figure 24.10 Sources of Inflationary Pressure in the AD/AS Model (a) A shift in aggregate demand, from AD0 to AD1, when it happens in the area of the SRAS curve that is near potential GDP, will lead to a higher price level and to pressure for a higher price level and inflation. The new equilibrium (E1) is at a higher price level (P1) than the original equilibrium. (b) A shift in aggregate supply, from SRAS0 to SRAS1, will lead to a lower real GDP and to pressure for a higher price level and inflation. The new equilibrium (E1) is at a higher price level (P1), while the original equilibrium (E0) is at the lower price level (P0).

An alternative source of inflationary pressures can occur due to a rise in input prices that affects many or most firms across the economy—perhaps an important input to production like oil or labor—and causes the aggregate supply curve to shift back to the left. In Figure 24.10 (b), the SRAS curve’s shift to the left also increases the price level from P0 at the original equilibrium (E0) to a higher price level of P1 at the new equilibrium (E1). In effect, the rise in input prices ends up, after the final output is produced and sold, passing along in the form of a higher price level for outputs.

The AD/AS diagram shows only a one-time shift in the price level. It does not address the question of what would cause inflation either to vanish after a year, or to sustain itself for several years. There are two explanations for why inflation may persist over time. One way that continual inflationary price increases can occur is if the government continually attempts to stimulate aggregate demand in a way that keeps pushing the AD curve when it is already in the SRAS curve’s steep portion. A second possibility is that, if inflation has been occurring for several years, people might begin to expect a certain level of inflation. If they do, then these expectations will cause prices, wages and interest rates to increase annually by the amount of the inflation expected. These two reasons are interrelated, because if a government fosters a macroeconomic environment with inflationary pressures, then people will grow to expect inflation. However, the AD/AS diagram does not show these patterns of ongoing or expected inflation in a direct way.

Importance of the Aggregate Demand/Aggregate Supply Model

Macroeconomics takes an overall view of the economy, which means that it needs to juggle many different concepts. For example, start with the three macroeconomic goals of growth, low inflation, and low unemployment. Aggregate demand has four elements: consumption, investment, government spending, and exports less imports. Aggregate supply reveals how businesses throughout the economy will react to a higher price level for outputs. Finally, a wide array of economic events and policy decisions can affect aggregate demand and aggregate supply, including government tax and spending decisions; consumer and business confidence; changes in prices of key inputs like oil; and technology that brings higher levels of productivity.

The aggregate demand/aggregate supply model is one of the fundamental diagrams in this course (like the budget constraint diagram that we introduced in the Choice in a World of Scarcity chapter and the supply and demand diagram in the Demand and Supply chapter) because it provides an overall framework for bringing these factors together in one diagram. Some version of the AD/AS model will appear in every chapter in the rest of this book.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e