18 Patents

Saylor Academy

Imagine that you invented the Apple iPhone 4. If you invent a patentable item that is useful, new, and nonobvious, and if you are capable of describing it in clear and definite terms, you may wish to protect your invention by obtaining a patent. A patent grants property rights to the inventor for a specified period of time, with a utility patent and a plant patent expiring twenty years following the original patent application and a design patent expiring fourteen years afterward. A patentee owns a patent.

Three patent types exist. Utility patents may be granted for machines, processes, articles of manufacture, compositions of matter, or for improvements to any of those items. The Apple iPhone 4 certainly is the subject of utility patents. A design patent may be granted for ornamental designs for an article of manufacture. A plant patent covers inventions or discoveries of asexually reproduced plants (e.g., plants produced through methods such as grafting).

Not all items are patentable. For instance, an idea alone (without a definite description) cannot be patented. So even if you dreamed up the idea of something that looked and functioned exactly like the Apple iPhone 4, you would not have been eligible for a patent on your idea alone. Likewise, physical phenomena, the laws of nature, abstract ideas, and artistic works cannot be patented. Note, however, that artistic works can be copyright protected. Additionally, otherwise patentable subjects that are not useful, or items that are offensive to public morality, are not patentable.

So what does it mean to have a patent? Just like real property ownership, a patent confers the right to exclude others. If you owned a parcel of real property, your ownership interest would allow you to exclude others from your land. The rule of law would protect your right to exclude against the intrusions of others, which is the very essence of ownership. Likewise, a patent confers the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling the patented product. This is consistent with the Copyright Clause of the U.S. Constitution, which grants inventors the “exclusive Right to their…Discoveries.” For others to legally make, use, or sell the patented product, they would have to be granted permission by the patentee. This is often accomplished through a licensing agreement, in which the patentee authorizes others to sell, make, or use the product.

You might be wondering how a patent can be granted over a living thing, like a plant. As mentioned earlier in this section, in the United States living things are patentable. Living things became the legal subjects of patents when, in 1980, the U.S. Supreme Court held that a bacterium designed by its inventor to break down crude oil components was the legitimate object of a patent.Diamond v. Chakrabarty, 447 U.S. 303 (1980). Indeed, as the Supreme Court noted in that case, congressional intent regarding the U.S. Patent Act was that “anything under the sun that is made by man” is patentable. Since then, we have seen many living organisms patented.

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) grants property rights to patentees within the United States, its territories and possessions. Patent law is complicated, and attorneys who wish to prosecute patents (file and interact with the USPTO) must have an engineering or science background and pass a separate patent bar exam. When an application is filed, the USPTO assigns a patent examiner to decide whether the patent application should be approved. While the application is pending, the applicant is permitted to use the term “patent pending” in marketing the product to warn others that a patent claim has been filed. Even after a patent has been issued by the USPTO, however, the patent is merely “presumed” to be valid. If someone challenges a patent in a lawsuit, final validity rests with the U.S. federal courts. For decades, the U.S. Supreme Court routinely ignored patent appeals, allowing lower courts to develop patent law. In recent years, under Chief Justice John Roberts, the Supreme Court has dramatically increased its acceptance of patent disputes, perhaps as a sign that the Court believes too many patents have been issued.

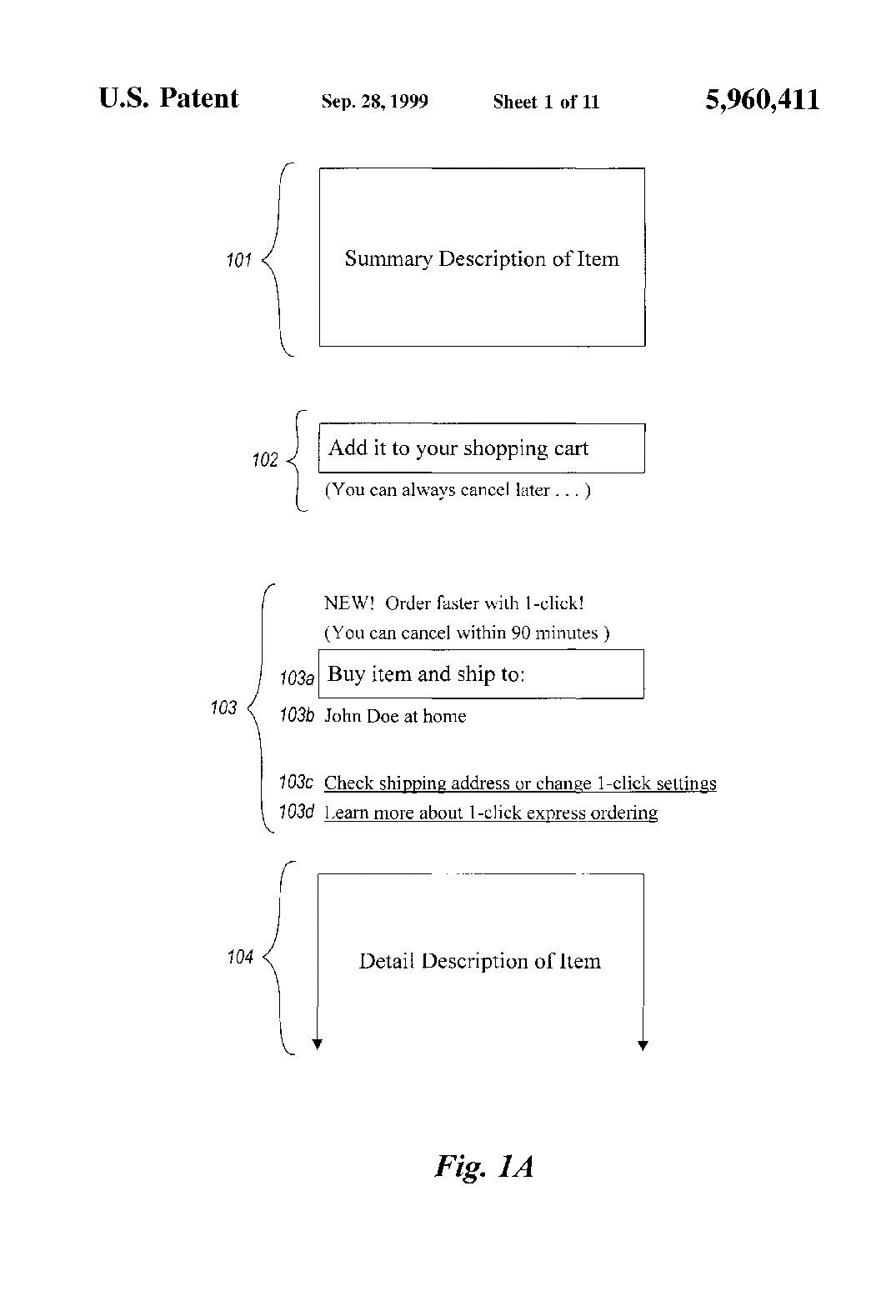

In the last decade there has been an over 400 percent increase in the number of patents filed, resulting in a multiyear delay in processing applications. An increase in the number of business method patents contributed to this dramatic increase in patent applications. A business method patent seeks to monopolize a new way of conducting a business process. Figure 9.5 “Patent Filing for One-Click Web Ordering”, for example, describes a method of e-commerce by which a customer can order an item and pay for it immediately with just one click of a mouse button. This one-click patent was granted to Amazon.com, much to the chagrin of other online retailers such as Barnes & Noble, who were prohibited from using a similar checkout mechanism. Amazon licensed the patent to Apple so that it could feature one-click on its Web site.

Figure 9.5 Patent Filing for One-Click Web Ordering

Outside the United States, a patent granted by the USPTO does not protect the inventor’s interest in that property. Other steps must be taken by the inventor to protect those rights internationally. If someone possesses the patented object without permission from the patentee, then the possessor can be said to have infringed on the patent owner’s rights. Patent infringement is an actionable claim. A successful action may result in an injunction, treble damages, costs, and attorney’s fees. One defense to a patent infringement claim is to challenge the validity of the patent.

In recent years several companies that do nothing but sue other companies for patent infringement have emerged. These patent holding companies, sometimes called patent trolls by critics, specialize in purchasing patents from companies that are no longer interested in owning them and then finding potential infringers. One such company, NTP, sued Research in Motion (RIM), the maker of the BlackBerry device, for a key technology used to deliver the BlackBerry’s push e-mail feature. Faced with a potential shutdown of the service, RIM decided to settle the case for more than six hundred million dollars.